Saint Helena earwig

The Saint Helena earwig or Saint Helena giant earwig (Labidura herculeana) is an extinct species[2] of very large earwig endemic to the oceanic island of Saint Helena in the south Atlantic Ocean.[3]

| Saint Helena earwig | |

|---|---|

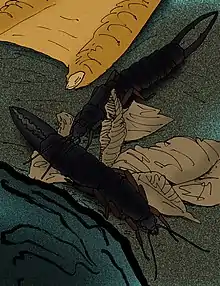

| |

| Preserved specimen in the Museum of Saint Helena, Jamestown, with dislocated posterior | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Dermaptera |

| Family: | Labiduridae |

| Genus: | Labidura |

| Species: | †L. herculeana |

| Binomial name | |

| †Labidura herculeana (Fabricius, 1798) | |

| |

| Location of Saint Helena | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Labidura loveridgei Zeuner, 1962 | |

Description

Growing as large as 84 mm (3.3 in) long (including forceps), the Saint Helena earwig was the world's largest earwig. It was shiny black with reddish legs, short elytra and no hind wings.[4]

Distribution and ecology

The earwig was endemic to Saint Helena, being found on the Horse Point Plain, Prosperous Bay Plain, and the Eastern Arid Area of the island. It was known to have lived in plain areas, gumwood forests and seabird colonies in rocky places. The earwig inhabited deep burrows, coming out only at night following rain. Dave Clark of the London Zoo said that "the females make extremely good mothers".[5] Known from subfossils remains, Saint Helena giant hoopoe could have been a predator of this earwig.[6]

History

The Saint Helena earwig was first discovered by Danish entomologist Johan Christian Fabricius, who named it Labidura herculeana in 1798. It later became confused with the smaller and more familiar shore earwig Labidura riparia, was demoted to a subspecies of that species in 1904 and received little attention from science.[2] It was all but forgotten until it was rediscovered in 1962 when two ornithologists, Douglas Dorward and Philip Ashmole, found some enormous dry tail pincers while searching for bird bones. They were given to zoologist Arthur Loveridge who confirmed they belonged to a huge earwig. The remains were forwarded to F. E. Zeuner, who named it as a new species Labidura loveridgei.[1]

In 1965, entomologists found live specimens in burrows under boulders in Horse Point Plain. While they were thought to be a separate species L. loveridgei, once examined they were found to be the same as L. herculeana, and this was reinstated as their official scientific name (L. loveridgei became a junior synonym). Other searches since the 1960s have not succeeded in finding the earwig.[2][7] It was allegedly last seen alive in 1967.[2]

On 4 January 1982, the Saint Helena Philatelic Bureau issued a commemorative stamp depicting the earwig, which brought attention to its conservation.[8] In the spring of 1988, a two-man search called Project Hercules was launched by London Zoo, but was unsuccessful.[7] In April 1995 another specimen of earwig remains was found. It proved that the earwigs not only lived in gumwood forests but, before breeding seabirds were wiped out by introduced predators, they also lived in seabird colonies.[9]

In 2005 Howard Mendel from the Natural History Museum conducted a search, with Philip and Myrtle Ashmole, to no avail.[10]

In 2023 British arachnologist Danniella Sherwood, with support from Saint Helenian colleagues from the government of Saint Helena and the Saint Helena National Trust, negotiated the donation and repatriation of a giant earwig specimen from the Royal Museum for Central Africa to Saint Helena, so that the island could have an intact specimen in their museum. The specimen arrived at the Museum of Saint Helena later the same year.[11]

Conservation status

The earwig has not been seen alive since 1967 despite searches for it in 1988, 1993, 2003 and 2005. It is possibly extinct due to habitat loss, "by the removal of nearly all surface stones.. ... for construction", as well as predation by introduced rodents, mantids, and centipedes (Scolopendra morsitans). In 2014, the IUCN changed their assessment of L. herculeana on the IUCN Red List from Critically Endangered to Extinct.[2]

References

- Zeuner, F. E. (1962). A subfossil giant Dermapteron from St. Helena. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 138: 651-653.

- D. Pryce & L. White (2014). "Labidura herculeana". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2014: e.T11073A21425735. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-3.RLTS.T11073A21425735.en.

- "Giant earwig". Insects and Spiders of the World. Vol. 4. Tarrytown, NY: Marshall Cavendish Corporation. 2003. p. 236. ISBN 0-7614-7338-6.

- "Labidura". St Helena and Ascension Island Natural History. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Worthington, P. (1988). "Over there, the topics ring all sorts of bells". Financial Post. p. 14.

- Julian P. Hume (2017). Extinct Birds. Christopher Helm. p. 242. ISBN 9781472937469. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- Shuker, Karl (1993). The Lost Ark. HarperCollins. pp. 235–236. ISBN 0002199432.

- Benson, Sonia; Nagel, Rob, eds. (2004). "Earwig, Saint Helena Giant". Arachnids, Birds, Crustaceans, Insects, and Mollusks. Endangered Species. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Detroit: UXL. pp. 482–483. ISBN 9780787676209.

- "The Invertebrates of Prosperous Bay Plain, St Helena: a survey" (DOC). St Helena and Ascension Island Natural History. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Chris Gower (January 2020). "Spotlight on Extinction: The St Helena Earwig". The Hourglass (4): 11.

- "St Helena Giant Earwig (Labidura herculeana) specimen returns to St Helena" (PDF). The Sentinel. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

External links

Media related to Labidura herculeana at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Labidura herculeana at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Labidura herculeana at Wikispecies

Data related to Labidura herculeana at Wikispecies- The Giant Earwig of St. Helena – The Dodo of the Dermaptera

- "It's giant earwigs versus aircraft on remote St Helena"

- "The giant earwig that could bring a country to a standstill"