Scottish Labour

Scottish Labour, officially the Scottish Labour Party,[7] (Scottish Gaelic: Pàrtaidh Làbarach na h-Alba) is the part of the UK Labour Party active in Scotland. Ideologically social democratic and unionist, it holds 22 of 129 seats in the Scottish Parliament and 2 of 59 Scottish seats in the House of Commons. It is represented by 262 of the 1,227 local councillors across Scotland. The Scottish Labour party has no separate Chief Whip at Westminster.

Scottish Labour Party | |

|---|---|

| |

| Labour Party Leader | Keir Starmer |

| Scottish Labour Leader | Anas Sarwar |

| Scottish Labour Deputy Leader | Jackie Baillie |

| General Secretary | John Paul McHugh[1] |

| Founded | 1888 (original form) 1994 (current form) |

| Headquarters | Rutherglen, South Lanarkshire, Scotland |

| Student wing | Scottish Labour Students |

| Youth wing | Scottish Young Labour |

| Membership (2021) | |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Centre-left |

| European affiliation | Party of European Socialists |

| International affiliation | Progressive Alliance, Socialist International (Observer) |

| Colours | Red |

| House of Commons (Scottish seats) | 2 / 59 |

| Scottish Parliament[4] | 22 / 129 |

| Local government in Scotland[5][6] | 282 / 1,227 |

| Website | |

| scottishlabour | |

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

Throughout the later decades of the 20th century and into the first years of the 21st, Labour dominated politics in Scotland; winning the largest share of the vote in Scotland at every UK general election from 1964 to 2010, every European Parliament election from 1984 to 2004 and in the first two elections to the Scottish Parliament in 1999 and 2003. After this, Scottish Labour formed a coalition with the Scottish Liberal Democrats, forming a majority Scottish Executive. More recently, especially since the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, the party has suffered significant decline; losing ground predominantly to the Scottish National Party, who advocate Scottish independence from the United Kingdom.

Scottish Labour experienced one of their worst defeats ever at the 2015 general election. They were left with a sole seat in the House of Commons, Edinburgh South, and lost 40 of its 41 seats to the SNP. This was the first time the party had not dominated in Scotland since the Conservative Party landslide in 1959.[8] At the 2016 Scottish Parliament election, the party lost 13 of its 37 seats, becoming the third-largest party after being surpassed by the Scottish Conservatives.

At the 2017 general election, Scottish Labour improved their fortunes and gained six seats from the SNP, bringing its total seat tally to seven and winning a 27% share of the vote. This was the first time since the 1918 general election, 99 years previously, that Labour had finished in third place at any general election in Scotland. Overall, the 2017 general election marked the first time in twenty years that the Labour Party had made net gains in the UK at any election.

The success was short-lived, however, and at the 2019 general election, Labour lost all new seats gained two years earlier, and again were left with Edinburgh South as their only Scottish seat in the House of Commons. Ian Murray has served as the MP for the constituency since 2010, and is currently one of Scotland's longest-serving MPs. The 2019 general election was Labour's worst result nationally in 84 years, with their lowest share of the vote recorded in Scotland since the December 1910 general election.

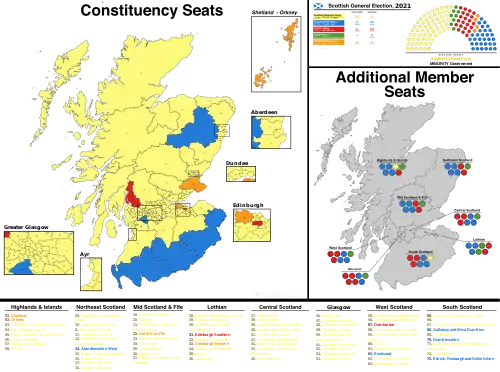

The 2021 Scottish Parliament election saw Labour decline even further, achieving their lowest number of seats in Holyrood since devolution in 1999; with 22 MSPs returned to the Scottish Parliament. Despite this, Anas Sarwar remained as leader.

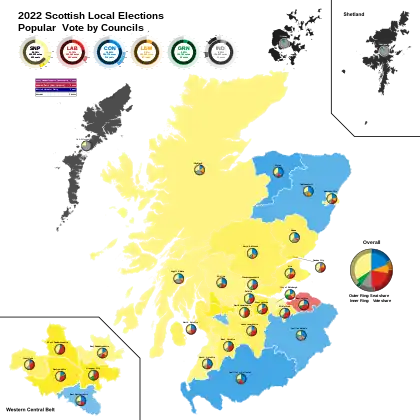

The 2022 Scottish local elections resulted in Labour gaining 20 seats across Scottish local councils, with a slight increase in their share of the vote.

Organisation

Scottish Labour is registered with the UK Electoral Commission as a description and Accounting Unit (AU) of the UK Labour Party and is therefore not a registered political party under the terms of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000.[9] As with Welsh Labour, Scottish Labour has its own general secretary which is the administrative head of the party, responsible for the day-to-day running of the organisation, and reports to the UK General Secretary of the Labour Party. The Scottish Labour headquarters is currently at Bath Street, Glasgow. It was formerly co-located with the offices of Unite the Union at John Smith House, 145 West Regent Street. The party holds an annual conference during February/March each year.

Scottish Executive Committee

Scottish Labour is administered by the Glasgow-based Scottish Executive Committee (SEC), which is responsible to the Labour Party's London-based National Executive Committee (NEC). The Scottish Executive Committee is made up of representatives of party members, elected members and party affiliates, for example, trade unions and socialist societies.

Party Officers:[10]

- Chair: Cara Hilton

- Vice Chair: Karen Whitefield

- Treasurer: Cathy Peattie

Membership

Labour Party full members (excluding affiliates and supporters)

In 2008, Scottish Labour membership was reported as 17,000, down from a peak of approximately 30,000 in the run-up to the 1997 general election.[11] The figures included in the Annual Report presented to the Scottish Party Conference in 2008, also recorded that more than half of all Constituency Labour Parties (CLPs) had less than 300 members, with 14 having less than 200 members.[12]

In September 2010, the party issued 13,135 ballot papers to party members during the Labour Party (UK) leadership election. These did not necessarily equate to 13,135 individual members – due to the party's electoral structure, members can qualify for multiple votes.[13] The party has declined to reveal its membership figures since 2008, and did not publish the number of votes cast in the leadership elections of 2011 or 2014, only percentages.[14]

In November 2014 the party's membership was claimed by an unnamed source reported in the Sunday Herald to be 13,500.[15] Other reports in the media at around this time quoted figures of "as low as 8,000" (the Evening Times)[16] and "less than 10,000" (New Statesman).[17] In December 2014 the newly elected leader Jim Murphy claimed that the figure was "about 20,000" on the TV programme Scotland Tonight.[18]

In late September 2015, following a membership boost resulting from the 2015 Labour leadership election, a total of 29,899 people were associated with the party; 18,824 members, 7,790 people affiliated through trade unions and other groups, and 3,285 registered supporters.[19]

In September 2017, it was reported that the party had 21,500 members and 9,500 affiliated through trade unions and other groups, making a total of 31,000 people associated with the party.[20]

In January 2018, the total Scottish membership stood at 25,836, however within 12 months it was leaked in January 2019 that this value had fallen by 4,674 to 21,162.[21]

In February 2021, the membership figure was down to 16,467.[2] Leaked figures obtained by the Daily Record in February 2022 showed that nearly one third of Scottish Labour members were in favour of another Scottish independence referendum. Asked whether "in principle" there should be a referendum on independence, 30% agreed and 57% disagreed.[22]

History

From the formation of the Labour Representation Committee in 1900, it had members in Scotland, but unlike in England and Wales, it made no pact with the Liberal Party and so initially struggled to make an impact.[23] In 1899, the Scottish Trades Union Congress organised the Scottish Workers' Representation Committee, which merged into the Labour Party in 1909, greatly increasing its presence in Scotland. By this time, the party's structure in the nation was complex, with constituency parties, and branches of affiliated parties, but no co-ordination at the national level. To provide this, a Scottish Advisory Council was founded in 1915, its first conference chaired by Keir Hardie.[24] This was later renamed as the Scottish Council of the Labour Party, informally known as the Labour Party in Scotland.[25][26] In 1994 or 1995, it was renamed as the Scottish Labour Party.[25][23] Under Kezia Dugdale, it was rebranded as Scottish Labour,[27] though its official name remains the Scottish Labour Party.

In the early years, the Scottish Council had little power, and its conference could only consider motions on Scottish matters until 1972. However, this allowed it to devote significant time to the question of Scottish devolution.[23] The Labour Party campaigned for the creation of a devolved Scottish Parliament as part of its wider policy of a devolved United Kingdom. In the late 1980s and 1990s it and its representatives participated in the Scottish Constitutional Convention with the Scottish Liberal Democrats, Scottish Greens, trades unions and churches, and also campaigned for a "Yes-Yes" vote in the 1997 referendum.

1999–2007: Coalition with Liberal Democrats

Donald Dewar led Labour's campaign for the first elections to the Scottish Parliament on 6 May 1999. Labour won the most votes and seats, with 56 seats out of 129 (including 53 of the 73 constituency seats), a clear distance ahead of the second-placed Scottish National Party (SNP). Labour entered government by forming a coalition with the Scottish Liberal Democrats, with Dewar agreeing to their demand for the abolition of up-front tuition fees for university students as the price for a coalition deal. Dewar became the inaugural First Minister of Scotland.[28]

Dewar died only a year later on 11 October 2000. A new first minister was elected in a ballot by Scottish Labour's MSPs and national executive members, because there was insufficient time to hold a full leadership election.[29] On 21 October, Henry McLeish was elected to succeed Dewar, defeating rival Jack McConnell.[30][31] Labour's dominance of Scotland's Westminster seats continued in the 2001 general election, with a small loss of votes but no losses of seats.

McLeish resigned later that year amid a scandal involving allegations that he sub-let part of his tax-subsidised Westminster constituency office without it having been registered in the register of interests kept in the Parliamentary office, an affair which the press called Officegate.[32] Though McLeish could not have personally benefited financially from the oversight, he undertook to repay the £36,000 rental income, and resigned to allow Scottish Labour a clean break to prepare for the 2003 Scottish Parliament election.[33] After McLeish's resignation, McConnell quickly emerged as the only candidate, and was elected First Minister by the Parliament on 22 November 2001.[34]

The coalition between Labour and the Liberal Democrats was narrowly re-elected at the Scottish Parliament election, with Labour losing seven seats and the Liberal Democrats gaining one.[35] The SNP also lost seats, though other pro-independence parties made gains. Labour once again won the majority of seats in Scotland at the 2005 general election. The boundaries in Scotland were redrawn to reduce the number of Westminster constituencies in Scotland from 72 to 59. Labour had a notional loss of 5 seats and an actual loss of 15.[36]

2007–2010: Opposition at Holyrood

At the start of the campaign for the 2007 Scottish Parliament election, Labour were behind the SNP in most of the opinion polls. On 10 April, McConnell unveiled Scottish Labour's election manifesto, which included plans to scrap bills for pensioners and reform Council Tax. The manifesto also proposed a large increase in public spending on education, which would allow for the school leaving age to be increased to 18 and reduce average class sizes to 19 pupils.[37]

Labour lost 4 seats and fell narrowly behind the SNP, who won 47 seats to Labour's 46 seats. Labour still won the most constituencies, but the SNP made inroads. Both parties were well short of a majority in the parliament.[38] SNP leader Alex Salmond was elected first minister with support from the Scottish Greens, defeating McConnell 49-46 while the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats abstained.[39][40] Labour did take the most votes in the local elections on the same day but lost seats due to the introduction of proportional representation for local council elections. On 15 August 2007, McConnell announced his intention to resign as Scottish Labour leader.[41] Wendy Alexander emerged as the only candidate to succeed him, and was installed as leader of the Labour group in the Scottish Parliament on 14 September 2007.[42]

During a TV interview on 4 May 2008, Wendy Alexander performed a major U-turn on previous Scottish Labour policy by seeming to endorse a referendum on Scottish independence, despite previously refusing to support any referendum on the grounds that she did not support independence. During a further TV interview two days later, she reiterated this commitment to a referendum and claimed that she had the full backing of current British Prime Minister Gordon Brown.[43] The following day, however, Brown denied this was Labour policy and that Alexander had been misrepresented during Prime Minister's Questions in Westminster.[44] Additionally, Brown's spokesman said: "The prime minister has always been confident of the strength of the argument in favour of the Union and believes a referendum on Scottish independence would be defeated."[43] Despite this lack of backing, Alexander once again reiterated her commitment to a referendum during First Minister's Questions in the Scottish Parliament.[45]

On 28 June 2008, Alexander announced her resignation as Leader of Scottish Labour as a result of the pressure on her following the donation scandal.[46][47] Cathy Jamieson subsequently became interim party leader. A month after, Labour lost a safe Westminster seat to the SNP in the Glasgow East by-election.[48][49]

The 2008 Labour group leadership election was the first time Labour had elected its Scottish leader with the participation of its members, using a system similar to that used at the time by the UK-wide Labour Party (the system had been adopted in 2007, but no ballot had taken place as Alexander had been unopposed). The contenders were Iain Gray, MSP for East Lothian, a former Enterprise Minister in the previous Labour Executive, Andy Kerr, MSP for East Kilbride and former Health Secretary in the previous administration, and Cathy Jamieson MSP, the acting party leader who had been deputy leader under Jack McConnell.[50][51] On 13 September 2008, Gray was elected leader and promised a "fresh start" for Labour in Scotland.[52]

A few months later, Labour won the Glenrothes by-election in Fife. The result was considered a surprise, as there was speculation that the SNP could have won an upset similar to Glasgow East.[53] The 2009 European Parliament election was catastrophic for Labour,[54] falling behind the SNP for the first time and producing its worst results since before World War I.[55] However, it easily won the Glasgow North East by-election later that year,[56] which had been triggered by the resignation of House Speaker Michael Martin in the wake of the expenses scandal.[57]

2010–2012: Re-evaluating position

At the 2010 general election on 6 May 2010, contrary to polls preceding the election, Labour consolidated their vote in Scotland, losing no seats (despite losing 91 seats across the rest of Britain) and regained Glasgow East from the SNP. This resulted in incumbent Scottish secretary Jim Murphy stating that the result provided an impetus for Scottish Labour to attempt to become "the biggest party in Holyrood" in the 2011 Scottish Parliament elections.[58]

Labour led the SNP in the polls for the 2011 Scottish Parliament election until the campaign began in March, at which point support for the SNP rallied. The SNP went on to win an unprecedented majority in the Scottish Parliament, a result that had been considered impossible under the proportional voting system. Labour had a net loss of 7 seats to the SNP. It also lost most of their constituency seats, although its share of the constituency vote declined by less than 1%. Labour's defeat was attributed to their campaign being directed mostly against the government in Westminster instead of the SNP.[59] Party leader Iain Gray, who held on to his own seat by only 151 votes, announced that he would be resigning with effect from later in the year. Eight weeks later, Labour easily retained a Westminster seat at the Inverclyde by-election, suggesting that Scottish Labour's disappointing performance in the 2011 Scottish Parliament election would not necessarily translate into support for its political opponents in other elections.

Following the 2011 Scottish election, Ed Miliband commissioned the Review of the Labour Party in Scotland of the future structure and operation of the Labour Party in Scotland, co-chaired by Murphy and Sarah Boyack MSP. The review included a recommendation for a new post of Leader of the Scottish Labour Party to be created (previous Scottish Labour leaders had only been the leader of the Labour group in the Scottish Parliament). Others included more autonomy for the Scottish party and the reorganisation of members into branches based on Holyrood constituencies rather than Westminster constituencies. On 17 December 2011, Johann Lamont MSP was elected as leader and Anas Sarwar MP was elected as her deputy. Delivering her victory speech, Lamont said: "I want to change Scotland, but the only way we can change Scotland is by changing the Scottish Labour Party."[60]

In the 2012 Scottish local elections, Labour were outpolled by the SNP. However, it gained votes and council seats and held its majorities on the councils of Glasgow and North Lanarkshire and regained control of Renfrewshire and West Dunbartonshire.[61]

2014 independence referendum and aftermath

For the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence, Scottish Labour joined with the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats to form the pro-union Better Together campaign against Scottish independence. It was led by Alistair Darling, a former Labour minister. In addition, Scottish Labour ran its own pro-UK campaign United with Labour alongside, with the support of former Prime Minister Gordon Brown.[62] Anas Sarwar MP also led an unofficial organisation called the "2014 Truth Team", described by the party as "dedicated to cutting through the noise and delivering [...] facts on independence".[63]

In July 2012, a member of Scottish Labour started Labour for Independence, a rebel group of Labour supporters who back Yes Scotland in the campaign for Scottish independence.[64] The group was dismissed by the Scottish Labour leadership as lacking "real support" from within the party.[65]

The referendum was held on 18 September 2014 and resulted in a 55.3%–44.7% victory for the No side. However, many of Labour's traditional strongholds favoured the Yes side, notably including Glasgow.[66] The SNP had a surge in membership[67] and gained a wide lead over Labour in the opinion polls.[68][69]

On 24 October 2014, Johann Lamont announced her resignation as leader. She accused Labour's UK-wide leadership of undermining her attempts to reform the Scottish Labour Party and treating it "like a branch office of London."[70] The party's 2014 leadership election was won by Jim Murphy, an MP who had previously served as Secretary of State for Scotland and been a prominent campaigner for the pro-Union side in the referendum.[71] In his victory speech, Murphy said that his election marked a "fresh start" for Scottish Labour: "Scotland is changing and so too is Scottish Labour. I'm ambitious for our party because I'm ambitious for our country".[71][72] He also said that he planned to defeat the SNP in 2016, and would use the increased powers being devolved to Holyrood to end poverty and inequality. In her speech after being elected deputy leader, Kezia Dugdale said that the party's "focus has to be on the future – a Scottish Labour party that's fighting fit and fighting for our future".[71]

2015–2021: Collapse at Westminster and further crisis in Holyrood

Labour's poll ratings in Scotland did not reverse, and the party suffered a landslide defeat in the general election in May 2015, losing 40 of their 41 seats to the SNP.[73] Many senior party figures were unseated, including Murphy himself (East Renfrewshire), Shadow Foreign Secretary Douglas Alexander (Paisley and Renfrewshire South) and Shadow Scotland Secretary Margaret Curran (Glasgow East).[74] Ian Murray (Edinburgh South) was the only MP re-elected.[75] It was the first time since 1959 that the party had not won the most votes in Scotland at a general election.[76] On 16 May 2015, Murphy resigned as leader effective 13 June 2015.[77] Under normal circumstances, Deputy Leader Kezia Dugdale would become acting leader, but former Leader Iain Gray was appointed Acting Leader whilst a leadership and a deputy leadership election are being simultaneously held on account of Dugdale resigning as Deputy Leader to stand for Leader. Dugdale won the 2015 leadership election on 15 August 2015, beating Ken Macintosh.[78][79] On 1 November 2015, Scottish Labour Party delegates backed a vote to scrap the UK's Trident nuclear missile system. The motion was supported by an overwhelming majority, in which both party members and unions voted 70% in favor of the motion.[80]

In the 2016 Scottish Parliament election, Labour lost a third of its seats, dropping from 37 to 24. Labour got its lowest percentage of the vote in Scotland in 98 years with 23% and fell into 3rd place, a position it last occupied in Scotland in 1910, behind the Conservatives. The party also only won 3 constituency seats: holding onto the Dumbarton and East Lothian constituencies and gaining the Edinburgh Southern constituency from the SNP, whilst losing eleven of its 2011 constituencies to the SNP and two to the Conservatives.[81]

In the 2017 local elections, Labour's share of first preference votes fell from 31.4% to 20.2%, while it lost over 130 seats. This result meant the Party fell to third place in terms of both vote share and number of councillors. Labour also lost control of Glasgow and three other councils where it had a majority.[82] At the beginning of the 2017 general election campaign, Labour's poll ratings fell to a historic low 13%, and were more than 15% behind the Conservatives in Scotland in some polls. However, towards the end of the campaign Labour's polling increased to levels around the 24% which it had received in 2015. On election day itself, the party managed to improve on its 2015 result and received 27% of the Scottish vote in a surprisingly good night for the party nationwide, and picked up 6 seats from the SNP in traditionally Labour areas such as Coatbridge, Glasgow, Kirkcaldy, and Rutherglen, bringing its Scottish number of seats to 7. Despite the positive result for the party, Labour remained in third place in Scotland, behind the Conservatives on 29%, and the SNP on 37%.[83]

On 29 August 2017, Dugdale resigned as leader of the Scottish Labour Party.[84] Her deputy, Alex Rowley, took over as acting leader until 15 November, when he was suspended from Scottish Labour's parliamentary party while a probe into his conduct took place.[85] Jackie Baillie took over as acting leader until the conclusion of the leadership election. The election for a new leader of the Scottish Labour party took place between 11 September 2017 (when nominations opened) and 18 November 2017, when the new leader was announced.[86][87] Nominations for leadership candidates closed on 17 September. Anyone that wished to vote in the leadership election must have either been a member of the Scottish Labour Party, an 'affiliated supporter' (through being signed up as a Scottish Labour Party supporter through an affiliated organisation or union), or a 'registered supporter' (which requires signing up online and paying a one-off fee of £12) by 9 October. Voting opened on 27 October and closed at midday on 17 November.[88][89] Richard Leonard won the leadership election with 56.7% of the vote and was elected as the leader of the Scottish Labour Party on 18 November.[90][91][92]

On 12 December 2019, Scottish Labour returned to having only one seat in Westminster (Edinburgh South).[93] Leonard apologised for the UK party failing to address concerns over Brexit and for the Scottish party not having stopped what he described as the "SNP juggernaut".[94] However, he said he would continue as leader and carry out a listening exercise.[95][96]

After surviving previous calls for him to go,[97][98] Leonard resigned as leader on 14 January 2021, triggering the 2021 Scottish Labour leadership election.[99] Shortly afterwards, it was reported that Leonard had been pressured into resigning by wealthy donors, who told UK Labour leader Keir Starmer that they would not give money to the Westminster party unless Leonard quit.[100]

2021–present: Anas Sarwar and opposition to second independence referendum

On 27 February 2021, former Deputy Leader Anas Sarwar was elected Leader of the Scottish Labour Party, defeating rival Monica Lennon by 57.6% to 42.4% and promised to heal and unite the party.[101] At the 2021 Scottish Parliament election, Labour lost a further two seats including the constituency seat of East Lothian, bringing their number of MSPs to 22, an all-time low.[102] They also recorded their worst performance on both the Constituency and List vote in terms of vote share, however it was better than had been predicted by many polls at the start of Sarwar's tenure as leader, some of which had predicted Labour to potentially fall to fourth place behind the Scottish Greens.[103] Under Sarwar's leadership, Scottish Labour have re-affirmed their constitutional position of unionism[104] which has led to a sometimes controversial selections of candidates. The party has been criticised for fielding a number of candidates affiliated with the Orange Order in local elections.[105][106]

In February 2022, during an interview on Times Radio, Sarwar said: "[Labour] have got to demonstrate to people the kind of alternative we can have and the difference it would make to people's lives so they positively vote Labour, not just negatively vote against the Tories or the SNP. If I'm honest, I didn't quite grip or grasp how I think hollowed out we were as an organisation, not just in terms of our political message and our political result, as an organisation I hadn't really grasped how hollowed out we were."[107] The party rebranded the following month, changing its traditional red rose logo to a red and purple thistle. A party spokesman said: "Scottish Labour is committed to transforming our party to win back the trust of the people to Scotland. We're on the side of the Scots, and hope they'll join us so we can build the future together. To do that we need new ideas and new thinking. At Scottish Labour conference this week you will hear Anas Sarwar relentlessly focus on the future."[108]

At the 2022 local elections, Labour made minor gains and overtook the Conservatives into second place by gaining 20 seats and a slight increase in their share of the vote, but still finished far behind the SNP; with 282 seats overall, it was Labour's second worst-worst result since 1977, beaten only by the 262 seats won in 2017.[109] The party was criticised in the aftermath of the elections for pledging to do no deals or partake in coalitions with the SNP or the Greens, instead choosing to work with the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats to form minority administrations in several cases.[110] In Edinburgh, they suspended two councillors for refusing to vote for the deal which gave Conservatives positions within the council.[111]

Sarwar, like Starmer, voiced his opposition to a proposed second Scottish independence referendum, stating that a Labour government would not grant a Section 30 order for one to be held.[112][113]

Elected representatives (current)

House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

- Ian Murray – MP for Edinburgh South since 2010. Shadow Secretary of State for Scotland 2015–2016 and since 2020

- Michael Shanks - MP for Rutherglen and Hamilton West since 2023

Holyrood spokespeople

As of April 2023[114]

- Anas Sarwar – Leader of the Scottish Labour Party

- Jackie Baillie – Deputy leader of Scottish Labour Party and general election campaign co-coordinator, Shadow Cabinet Secretary for NHS Recovery, Health and Social Care and Drugs Policy

- Ian Murray – Shadow Secretary of State for Scotland and general election campaign co-coordinator

- Neil Bibby – Shadow Cabinet Secretary for Constitution, External Affairs and Culture

- Sarah Boyack – Shadow Cabinet Secretary for Net Zero, Energy, and Just Transition

- Foysol Choudhury – Shadow Minister for Culture, Europe and International Development

- Katy Clark – Shadow Minister for Community Safety

- Pam Duncan-Glancy – Shadow Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills

- Rhoda Grant – Shadow Cabinet Secretary for Rural Affairs, Land Reform and Islands

- Mark Griffin – Shadow Minister for Local Government and Housing

- Daniel Johnson – Shadow Cabinet Secretary for Economy, Business and Fair Work

- Pauline McNeill – Shadow Cabinet Secretary for Justice

- Michael Marra – Shadow Cabinet Secretary for Finance

- Carol Mochan – Shadow Minister for Public Health and Women's Health

- Paul O'Kane – Shadow Cabinet Secretary for Social Justice and Social Security, and Equalities

- Paul Sweeney – Shadow Minister for Mental Health and Veterans

- Colin Smyth – Shadow Cabinet Secretary for Economic Development and Rural Affairs

- Alex Rowley - Shadow Minister for Transport

- Mercedes Villalba – Shadow Minister for Environment and Biodiversity

- Martin Whitfield – Business Manager and Shadow Minister for Children and Young People

Members of the 6th Scottish Parliament (2021–present)

| Member of the Scottish Parliament | Constituency or Region | First elected | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jackie Baillie | Dumbarton | 1999 | Deputy Leader of the Scottish Labour Party 2020–, Acting Leader of Scottish Labour 2014, 2017, 2021, Minister for Social Justice 2000–2001 |

| Claire Baker | Mid Scotland and Fife | 2007 | |

| Neil Bibby | West Scotland | 2011 | Chief Whip of the Scottish Labour Party 2014–2016 |

| Sarah Boyack | Lothian | 1999 | Member for Edinburgh Central 1999–2011, Lothian 2011–2016, 2019–, Minister for Transport and Planning from 1999 to 2001 |

| Foysol Choudhury | Lothian | 2021 | |

| Katy Clark | West Scotland | 2021 | MP for North Ayrshire and Arran 2005–2015 |

| Rhoda Grant | Highlands and Islands | 1999 | Member for Highlands and Islands 1999–2003, 2007– |

| Mark Griffin | Central Scotland | 2011 | |

| Daniel Johnson | Edinburgh Southern | 2016 | |

| Pam Duncan-Glancy | Glasgow | 2021 | The first permanent wheelchair user elected to the Scottish Parliament |

| Monica Lennon | Central Scotland | 2016 | |

| Richard Leonard | Central Scotland | 2016 | Leader of the Scottish Labour Party, 2017–2021 |

| Michael Marra | North East Scotland | 2021 | |

| Pauline McNeill | Glasgow | 1999 | Member for Glasgow Kelvin 1999–2011, Glasgow 2016– |

| Carol Mochan | South Scotland | 2021 | |

| Paul O'Kane | West Scotland | 2021 | |

| Alex Rowley | Mid Scotland and Fife | 2014 | Member for Cowdenbeath 2014–2016, Acting Leader of Scottish Labour 2017, Deputy Leader of the Scottish Labour Party 2015–2017 |

| Anas Sarwar | Glasgow | 2016 | MP for Glasgow Central 2010–2015, Acting Leader of Scottish Labour 2014, Deputy Leader of the Scottish Labour Party 2011–2014, Leader of the Scottish Labour Party 2021– |

| Colin Smyth | South Scotland | 2016 | |

| Paul Sweeney | Glasgow | 2021 | MP for Glasgow North East 2017–2019 |

| Mercedes Villalba | North East Scotland | 2021 | |

| Martin Whitfield | South Scotland | 2021 | MP for East Lothian, 2017–2019 |

Appointments

House of Lords

| Date ennobled | Name | Title |

|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Derry Irvine | Baron Irvine of Lairg |

| 1994 | Helen Liddell | Baroness Liddell of Coatdyke |

| 1995 | Elizabeth Smith | Baroness Smith of Gilmorehill |

| 1996 | Meta Ramsay | Baroness Ramsay of Cartvale |

| 1997 | Robert Hughes | Baron Hughes of Woodside |

| 1997 | Helena Kennedy | Baroness Kennedy of The Shaws |

| 1997 | Mike Watson | Baron Watson of Invergowrie |

| 1997 | Barbara Young | Baroness Young of Old Scone |

| 1999 | Murray Elder | Baron Elder |

| 1999 | Hector MacKenzie | Baron MacKenzie of Culkein |

| 2000 | George Robertson | Baron Robertson of Port Ellen |

| 2004 | Alexander Leitch | Baron Leitch |

| 2004 | John Maxton | Baron Maxton |

| 2005 | Irene Adams | Baroness Adams of Craigielea |

| 2005 | George Foulkes | Baron Foulkes of Cumnock |

| 2006 | Neil Davidson | Baron Davidson of Glen Clova |

| 2010 | Des Browne | Baron Browne of Ladyton |

| 2010 | Tommy McAvoy | Baron McAvoy |

| 2010 | Jack McConnell | Baron McConnell of Glenscorrodale |

| 2010 | John Reid | Baron Reid of Cardowan |

| 2010 | Wilf Stevenson | Baron Stevenson of Balmacara |

| 2013 | Willie Haughey | Baron Haughey |

| 2018 | Pauline Bryan | Baroness Bryan of Partick |

| 2018 | Iain McNicol | Baron McNicol of West Kilbride |

Electoral performance

House of Commons

| Election | Scotland | +/– | Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Seats | |||

| Jan 1910 | 5.1 | 2 / 70 |

3rd | |

| Dec 1910 | 3.6 | 3 / 70 |

3rd | |

| 1918 | 22.9 | 6 / 71 |

4th | |

| 1922 | 32.2 | 29 / 71 |

1st | |

| 1923 | 35.9 | 34 / 71 |

1st | |

| 1924 | 41.1 | 26 / 71 |

2nd | |

| 1929 | 42.3 | 36 / 71 |

1st | |

| 1931 | 32.6 | 7 / 71 |

3rd | |

| 1935 | 36.8 | 20 / 71 |

2nd | |

| 1945 | 47.9 | 37 / 71 |

1st | |

| 1950 | 46.2 | 37 / 71 |

1st | |

| 1951 | 47.9 | 35 / 71 |

2nd | |

| 1955 | 46.7 | 34 / 71 |

2nd | |

| 1959 | 46.7 | 38 / 71 |

1st | |

| 1964 | 48.7 | 43 / 71 |

1st | |

| 1966 | 49.8 | 46 / 71 |

1st | |

| 1970 | 44.5 | 44 / 71 |

1st | |

| Feb 1974 | 36.6 | 40 / 71 |

1st | |

| Oct 1974 | 36.3 | 41 / 71 |

1st | |

| 1979 | 41.6 | 44 / 71 |

1st | |

| 1983 | 35.1 | 41 / 72 |

1st | |

| 1987 | 42.4 | 50 / 72 |

1st | |

| 1992 | 39.0 | 49 / 72 |

1st | |

| 1997 | 45.6 | 56 / 72 |

1st | |

| 2001 | 43.3 | 56 / 72 |

1st | |

| 2005 | 39.5 | 41 / 59 |

1st | |

| 2010 | 42.0 | 41 / 59 |

1st | |

| 2015 | 24.3 | 1 / 59 |

2nd | |

| 2017 | 27.1 | 7 / 59 |

3rd | |

| 2019 | 18.6 | 1 / 59 |

4th | |

Scottish Parliament

| Election | Constituency | Regional | Total seats | +/– | Rank | Government | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Seats | Votes | % | Seats | |||||

| 1999 | 908,346 | 38.8 | 53 / 73 |

786,818 | 33.6 | 3 / 56 |

56 / 129 |

Lab–LD | ||

| 2003 | 663,585 | 34.6 | 46 / 73 |

561,375 | 29.3 | 4 / 56 |

50 / 129 |

Lab–LD | ||

| 2007 | 648,374 | 32.1 | 37 / 73 |

595,415 | 29.2 | 9 / 56 |

46 / 129 |

Opposition | ||

| 2011 | 630,461 | 31.7 | 15 / 73 |

523,469 | 26.3 | 22 / 56 |

37 / 129 |

Opposition | ||

| 2016 | 514,261 | 22.6 | 3 / 73 |

435,919 | 19.1 | 21 / 56 |

24 / 129 |

Opposition | ||

| 2021 | 584,392 | 21.6 | 2 / 73 |

485,819 | 17.9 | 20 / 56 |

22 / 129 |

Opposition | ||

See also

References

- "Former union man takes on top job at Scottish Labour". The National.

- Hutcheon, Paul (3 February 2021). "Scottish Labour 'crisis' after leaked figures show fall in membership". Daily Record. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- Nordsieck, Wolfram (2016). "Scotland/UK". Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- "MSPs". Parliament.scot. 3 November 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- "Local Council Political Compositions". Open Council Date UK. 7 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- "Labour councillor suspended in Sarwar row". bbc.co.uk. 21 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Although officially named the Scottish Labour Party, Scottish Labour is not a political party. It is registered with the UK Electoral Commission as a description and Accounting Unit (AU) of the UK Labour Party and is therefore not a registered political party under the terms of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000.

- "1959 General Election". History Learning Site. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- "Labour Party Registration". UK Electoral Commission. 14 January 1999. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- "Who's on the SEC?". Scottish Labour. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- "Labour membership at record low". Scotland Discussion Forum. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Low, Stephen (29 March 2008). "Labour foot soldiers fall away". BBC News.

- Macdonell, Hamish (29 September 2010). "The Scottish Labour Party and its mysterious expanding membership". Caledonian Mercury. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- "Lamont is Scottish Labour leader". BBC News. 17 December 2011.

- "Revealed: just how many members does Labour really have in Scotland?". Sunday Herald. 9 November 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- "Other parties should copy Sturgeon's US-style rallies". Evening Times. 17 October 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "Leader: The end of the "two-party" party". New Statesman. 6 November 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "Start as you mean to go on". Wings Over Scotland. 16 December 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- Whitaker, Andrew (27 September 2015). "Interview: Kezia Dugdale on reform of Scots Labour". The Scotsman.

- Hutcheon, Paul (3 September 2017). "Top Scottish Labour donor backs millionaire Sarwar as next party leader". The Herald.

- Hutcheon, Paul (2 January 2019). "Blow for Richard Leonard as leak reveals 5,000 Labour membership slump across Scotland". The Herald.

- Hutcheon, Paul (1 February 2022). "One third of Scottish Labour voters support second referendum on independence". Daily Record. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- Peter Barberis et al., Encyclopedia of British and Irish Political Organizations, pp.397–398

- David Clark and Helen Corr, "Shaw, Benjamin Howard", Dictionary of Labour Biography, vol.VIII, pp.226–229

- Hassan, Gerry (20 June 2012). Strange Death of Labour Scotland. Edinburgh University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-7486-5555-7.

- Report of the Annual Conference of the Labour Representation Committee. Labour Representation Committee. 1982. p. 32. ISBN 9780861170937.

- Morrison, James (2021). Essential Public Affairs for Journalists. Oxford University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-19-886907-8.

- STV News (2 May 2019). "Scotland's first coalition government 'almost didn't happen'". STV News.

- Scott, Kirsty (23 October 2000). "Dewar's successor to seek more power for parliament". The Guardian.

- Millar, Stuart (22 October 2000). "McLeish scores narrow victory". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- Hassan, Gerry (2019). Story of the Scottish Parliament: The First Two Decades Explained. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-5492-6. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- English, Shirley (22 March 2003). "McLeish cleared over 'Officegate'". The Times. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "McLeish steps down". BBC News. 8 November 2001. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- Tempest, Matthew (22 November 2001). "McConnell appointed Scotland's first minister in 'coronation' vote". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- Quinn, Joe; Darroch, Gordon; PA News (2 May 2003). "Labour grip slackens in Scotland". The Independent. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "Move to cut two Scottish MPs and weaken Scotland's voice at Westminster". Business for Scotland. 14 October 2021.

- "Scottish Labour pledge to put 'education first'". Politics Home. 10 April 2007. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Scottish defeat leaves problem for Blair successor". Reuters. 5 May 2007 – via www.reuters.com.

- "Salmond takes reins as nationalist first minister". Public Finance. 17 May 2007.

- Booth, Jenny; PA News (16 May 2007). "Salmond elected Scotland's First Minister". The Times.

- "McConnell quits as Scottish Labour leader". The Guardian. 15 August 2007.

- Holt, Richard (21 August 2007). "Wendy Alexander to be Scottish Labour leader". The Daily Telegraph.

- Bolger, Andrew; Parker, George (7 May 2008). "Alexander defends U-turn on Scottish vote". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Gordon Brown snubs Wendy Alexander over referendum call". Daily Record. 7 May 2008.

- "Referendum switch betrays Labour panic". The Herald. 6 May 2008.

- "Scots Labour leader Wendy Alexander resigns after allegations of". Evening Standard. 13 April 2012.

- Hinsliff, Gaby; Kelbie, Paul (28 June 2008). "Alexander quits over funding scandal". The Guardian.

- "SNP stuns Labour in Glasgow East". BBC News. 24 July 2008.

- "Glasgow East by-election: SNP storm to historic election victory by 365 votes". The Scotsman. 24 July 2008.

- Schofield, Kevin (4 August 2008). "Exclusive: Labour at war as MPs dismiss call for more power for party's Holyrood leader". Daily Record.

- Allardyce, Jason (6 July 2008). "Cathy Jamieson tipped to lead Labour" – via www.thetimes.co.uk.

- "Iain Gray is Scottish Labour leader". Metro. 13 September 2008.

- "Glenrothes result in full". BBC News. 7 November 2008.

- "European elections 2009: SNP beats Labour into second in Scotland". www.telegraph.co.uk. 8 June 2009. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- Carrell, Severin (8 June 2009). "European elections: Labour plays down SNP's emphatic win in Scotland". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- Weir, Keith (13 November 2009). "Labour wins in Glasgow North East". Reuters. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- Mason, Peter (18 November 2009). "Glasgow North East by-election: Mass abstentions in Labour's 'surprise win'". Socialist Party of Great Britain. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- Gardham, Magnus. "Election 2010: Jim Murphy's joy as Scotland says no to David Cameron". Daily Record. Archived from the original on 11 May 2010. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Black, Andrew (6 May 2011). "Scottish Election: Campaign successes and stinkers". BBC News. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- "Johann Lamont named new Scottish Labour leader". BBC News. 17 December 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Carrell, Severin (6 May 2012). "SNP won 'remarkable victory' in Scottish elections, says Alex Salmond". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Scottish independence: Former PM Gordon Brown wants a 'union for social justice'". BBC News. 13 May 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- "Anas Sarwar MP launches the 2014 Truth Team". 22 April 2013. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Dinwoodie, Robbie (30 July 2012). "Yes Scotland wins support from Labour rebel group". The Herald. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- McNab, Scott (30 July 2012). "Scottish independence: Labour dismisses rebellion". The Scotsman. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- "Johann Lamont 'will stay on as Labour leader'". The Scotsman. Johnston Press. 26 September 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- "SNP membership trebles following indyref". The Herald. Herald & Times Group. 1 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- Lambert, Harry (21 October 2014). "Could the SNP win 25 Labour seats in 2015?". New Statesman. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Singh, Matt (16 October 2014). "Scotland update: Is the SNP surge real?". Number Cruncher Politics. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Cochrane, Alan (24 October 2014). "Johann Lamont to resign as Scottish Labour leader". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- "MP Jim Murphy named Scottish Labour leader". BBC News. BBC. 13 December 2014. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- Johnston, Chris; Brooks, Libby (13 December 2014). "Jim Murphy is announced as leader of Scottish Labour party". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- Devine, Tom (2 March 2016). "The strange death of Labour Scotland". New Statesman. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- "Election 2015: Scottish Labour leader Murphy loses seat to SNP". BBC News. 8 May 2015.

- "Ian Murray: the last Scottish Labour MP standing". The Guardian. 4 June 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- Duclos, Nathalie (2015). "The 2015 British General Election: a Convergence in Scottish Voting Behaviour?". Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique. French Journal of British Studies. 20 (3). doi:10.4000/rfcb.639. ISSN 0248-9015. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- Dearden, Lizzie (16 May 2015). "Jim Murphy quits as Scottish Labour leader despite confidence vote – and bows out with swipe at Len McCluskey". The Independent. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- "Kezia Dugdale elected Scottish Labour leader". The Guardian. 15 August 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- Cusick, James (15 August 2015). "Kezia Dugdale: Scottish Labour's new leader, 33, claims optimism of youth". The Independent. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- "Scottish Labour votes to scrap Trident". BBC News. 1 November 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- "2016 Scottish Parliament election: Results analysis". Scottish Parliament. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- "Full Scottish council election results published". BBC News. 8 May 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- "General election 2017: SNP lose a third of seats amid Tory surge". BBC News. 9 June 2017.

- "Kezia Dugdale quits as Scottish Labour leader". BBC News. 29 August 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- "Labour suspends deputy leader Alex Rowley during conduct probe". BBC News. 15 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "Scottish Labour leadership: Date set for leader announcement". BBC News. 9 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- Carrell, Severin (4 September 2017). "Sarwar and Leonard confirm bids for Scottish Labour leadership". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- "Information about Leadership election 2017". Scottish Labour Party. 14 September 2017. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- Howarth, Angus (9 September 2017). "Timetable announced for Scottish Labour leadership race". The Scotsman. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- "Scottish Leadership Result 2017". Scottish Labour. 18 November 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- "Richard Leonard to lead Scottish Labour". BBC News. 18 November 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- Carrell, Severin (18 November 2017). "Richard Leonard voted Scottish Labour leader". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- Swanson, Ian (13 December 2019). "General Election Results 2019: Ian Murray holds Edinburgh South in catastrophic night for Labour". Edinburgh News. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- "Labour swept aside by SNP juggernaut says Richard Leonard". The Herald. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- Learmonth, Andrew (13 December 2019). "Labour's Richard Leonard: I can still be First Minister". The National. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- "Labour consider 'listening exercise' after defeat". BBC News. 14 December 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- Hutcheon, Paul (2 September 2020). "Fourth Labour MSP calls on party leader Richard Leonard to quit". Daily Record. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- Gordon, Tom (3 September 2020). "Starmer ally urges Leonard to resign as Scottish Labour leader". The Herald. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Rocks, Chelsea (15 January 2021). "Richard Leonard MSP: why did Scottish Labour leader resign, what were his policies, and why was he criticised?". The Scotsman. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- Findlay, Neil (15 January 2021). "How Not to Save Scottish Labour". Tribune.

- Rodgers, Sienna (27 February 2021). "Anas Sarwar elected as new leader of Scottish Labour Party". LabourList.

- Christie, Niall (9 May 2021). "Sarwar 'proud' of Labour's election showing despite recording worst ever result in Scotland". Morning Star.

- "Scottish Parliament Polling". Ballot Box Scotland. 7 January 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- Henderson, Ailsa (26 June 2020). "Labour must be careful in chasing the unionist vote". The Times.

- Morrison, Hamish (4 March 2022). "Anas Sarwar: Orange Order 'tolerance' challenge fired at Labour". The National. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Learmonth, Andrew (29 July 2019). "Scottish Labour councillor gets top job at Orange Order". The National. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- McKenzie, Lewis (14 February 2022). "Sarwar: 'I didn't grasp how hollowed out Scottish Labour was'". STV News.

- "Scottish Labour to ditch red rose in rebranding". BBC News. 2 March 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- Garton-Crosbie, Abbi (10 July 2022). "Scottish Labour's Anas Sarwar is rattled by The National's questions on Tory deals". The National. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- Matchett, Conor (19 May 2022). "Scottish Labour have tied themselves in knots over local government coalitions". The Scotsman. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- Swanson, Ian (28 June 2022). "Two Edinburgh Labour councillors suspended after abstaining on vote which put their party into power". Edinburgh News. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- Forrest, Adam (4 July 2022). "Putin would welcome Scottish independence, claims Labour's Anas Sarwar". The Independent. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- "Is Labour's rightward shift making Scots back independence?". openDemocracy. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- Gordon, Tom (10 April 2023). "Anas Sarwar boasts Scottish Labour 'election ready' after shake-up". The Herald.

- "Scottish Peers". Scottish Labour.

- "EU Elections 2019: SNP secures three seats as Labour vote collapses". BBC News. 27 May 2019.

Further reading

- Alexander, Wendy (2005), Donald Dewar, Scotland's First Minister, Mainstream Publishing, ISBN 9781845960384

- Hassan, Gerry (2003),The Scottish Labour Party, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 0-7486-1784-1

- Hassan, Gerry; Shaw, Eric (2012), The Strange Death of Labour Scotland, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 0748640029

- Henderson, Ailsa; Johns, Rob; Larner, Jac; and Carman, Chris (2020), "Scottish Labour as a case study in party failure: Evidence from the 2019 UK General Election in Scotland." Scottish Affairs

- Keating, Michael; Bleiman, David (1979), Labour and Scottish Nationalism, Macmillan, ISBN 9780333265963

- Keating, Michael (1983), Labour and Scottish Nationalism: An Update, in Hearn, Sheila G. (ed.), Cencrastus No. 12, Spring 1983, pp. 29 – 31, ISSN 0264-0856

- Knox, William W. (1984), Scottish Labour Leaders 1918 – 1939: A Biographical Dictionary, Mainstream Publishing, ISBN 9780906391402

- Rosen, Greg (2001), Dictionary of Labour Biography, Politicos Publishing, ISBN 1-902301-18-8

- Rosen, Greg (2005), Old Labour to New, Politicos Publishing.

- Stuart, Mark (2005), John Smith – A Life, Politicos Publishing, ISBN 9781842751268