Labral reconstruction

Labral reconstruction is a type of hip arthroscopy in which the patient's native labrum is partially or completely removed and reconstructed using either autograft or allograft tissue. Originally described in 2009[1] using the ligamentum teres capitis, arthroscopic labral reconstruction using a variety of graft tissue has demonstrated promising short and mid-term clinical outcomes.[2][3][4] Most importantly, labral reconstruction has demonstrated utility when the patient's native labral tissue is far too damaged for debridement or repair.[5]

| Labral reconstruction | |

|---|---|

Arthroscopic view of the superior acetabular labrum status-post circumferential labral reconstruction with ITB allograft. Note restoration of the labral suction-seal. Surgery performed by Dr. Andrew B Wolff of Washington Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine. | |

| Specialty | orthopedic |

Anatomy

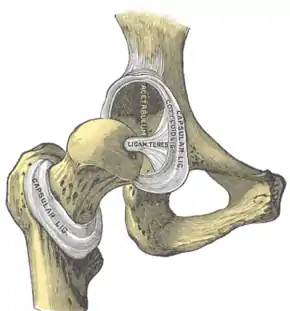

The acetabular labrum is a fibrocartilagenous structure similar in composition to the meniscus. It is a ring of tissue that surrounds the acetabulum of the pelvis, and allows the head of the femur to articulate smoothly and efficiently with the acetabulum. The labrum plays an important role in maintaining the biomechanical stability of the hip joint. Studies[6] have shown that damage to the labral tissue can result in disruption of the labral suction-seal, a fluid force paramount in maintaining hip joint integrity. An intact labrum also helps to buttress the hip joint to distraction forces.[7] The labrum, when damaged, is also a pain generator, due to a large concentration of type II pain-associated free nerve endings found throughout the tissue, most pronounced at the labral base.[8]

History

Labral reconstruction was first described in 2009 by Sierra et al.[1] The procedure described in their article described reconstructing a patient's native labrum with a ligamentum teres capitis graft. This was done in the setting of an open surgical hip dislocation. Prior to the introduction of labral reconstruction, complex labral tears were often treated with removal of damaged tissue (debridement) or focal repair. The applicability of these methods to severe or widespread labral damage is less than ideal. Since then, surgeons have reported on a variety of graft choices and surgical techniques, and an arthroscopic approach has usurped open dislocation, due to fewer complications, a lower need for revision surgery and quicker recovery time.[9][10]

Indications

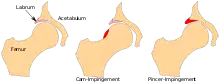

Labral reconstruction, while still a relatively novel technique, has demonstrated utility and efficacy in treating labral tears in patient's whose native labral tissue is far too damaged for arthroscopic debridement or repair.[5] It is most often utilized in order to surgically correct the damage resulting from femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), a condition in which the femoral head articulates imperfectly with the acetabular cup. Labral damage resulting from FAI or other conditions exists on a spectrum, with varying degrees of labral damage necessitating different surgical management. The most mild degrees of labral damage can be managed with arthroscopic debridement, a procedure in which the damaged tissue is excised with an arthroscopic shaver or electrocautery device. More moderate damage responds better to arthroscopic labral repair, a procedure in which surgical anchors are drilled into the bony acetabular rim and sutures are used to reapproximate the damaged labral tissue. The most severe degrees of labral pathology is often unresponsive to labral repair, with damage far too diffuse for focal debridement. In these cases, labral reconstruction is the best option for not only restoring the biomechanics of the acetabular labrum, but for treatment of the patient's pain.

A recent multicenter epidemiological study found that the majority of patients undergoing labral reconstruction are middle-aged females whose pain is localized around the groin.[11] Patient pain is ofter exacerbated by sitting and athletic activities. Many patients undergoing labral reconstruction have failed conservative therapy, which typically includes intra-articular injections and physical therapy. A majority of patients have abnormal acetabular or femoral bony morphology typical of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI).

Technique

Graft selection

A variety of graft options for labral reconstruction have been proposed. Although the literature for ACL reconstruction has demonstrated more favorable outcomes with autograft tissue versus allograft, no such relationship has been found to exist for labral reconstruction. Drs. Brian White and Andrew Wolff, two sports medicine trained surgeons specializing in hip arthroscopy, both prefer the utilization of allograft tissue.[12][13] The surgeons who advocate for the use of allograft tissue feel that the control over graft thickness, consistency and size, in addition to the absence of donor site morbidity make it the preferred graft choice for this procedure. Other graft options include iliotibial band autograft, hamstrings autograft or quadriceps tendon autograft.[5] Currently, there is a lack of sufficient data to claim one graft choice superior to the others.

Segmental vs. circumferential/front-to-back

Traditionally, only the damaged labral tissue was resected, and the graft was attached to both the acetabulum and the native labral tissue. This method demonstrated superiority over straight debridement in the treatment of irreparable labral tears.[5] There was concern by some surgeons, however, that the junction points between the native labrum and graft were inherently weak, and thus prone to failure.[12] There was also concern that despite resection of the visibly damaged tissue there existed the possibility for underresection, which could lead to persistent pain despite restoration of the labral biomechanics.

Recently, surgeons have begun experimenting with circumferential (front-to-back) reconstruction in which the entirety of the native labral tissue is debrided, and the labrum is completely reconstructed.[12] This technique has shown promising outcomes when utilized in patients whose native labral tissue is far too damaged for repair or debridement. A recent study comparing primary labral reconstruction versus primary labral repair demonstrated higher failure rates in the repair cohort versus the reconstruction cohort.[14]

Outcomes

Arthroscopic labral reconstruction has demonstrated favorable outcomes, which have become more pronounced as techniques and technology continue to develop. Arthroscopic labral reconstruction has shown comparable outcomes to labral repair, despite the fact that those patients who undergo reconstruction typically have far more severe labral damage.[3] Recent studies have shown not only equivalent outcomes between labral reconstruction and labral repair, but improved outcomes for labral reconstruction for patients with more moderate degrees of labral damage. Labral reconstruction also has proven utility in the hips of elite athletes and other high-demand patients.[15]

Complications

The complications encountered during and after labral reconstruction are similar to arthroscopic procedures involving the hip.[16]

Anesthetic complications

Anesthetic complications are rare, but include urinary retention, gastrointestinal upset, cardiac complications and even death.

Operative complications

As with all surgery, arthroscopic labral reconstruction has a small risk of infection. Damage to the surrounding neurovasculature is possible, but this risk is minimized through meticulous surgical technique. The most commonly injured nerve is the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, although this risk is very low with proper arthroscopic portal placement. A new postless table designed by Stryker has nearly eliminated the risk of postoperative saddle parasthesia, which was previously a common complication. Post-operative deep-vein thrombosis is also possible, but the rate of this complication can be minimized through the use of blood thinning medications and early ambulation.

References

- Sierra, Rafael J.; Trousdale, Robert T. (2009-03-01). "Labral Reconstruction Using the Ligamentum Teres Capitis: Report of a New Technique". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 467 (3): 753–759. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0633-5. ISSN 0009-921X. PMC 2635467. PMID 19048354.

- Philippon, Marc J.; Briggs, Karen K.; Hay, Connor J.; Kuppersmith, David A.; Dewing, Christopher B.; Huang, Michael J. (2010). "Arthroscopic Labral Reconstruction in the Hip Using Iliotibial Band Autograft: Technique and Early Outcomes". Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 26 (6): 750–756. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2009.10.016. PMID 20511032.

- Matsuda, Dean K.; Burchette, Raoul J. (May 2013). "Arthroscopic hip labral reconstruction with a gracilis autograft versus labral refixation: 2-year minimum outcomes". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 41 (5): 980–987. doi:10.1177/0363546513482884. ISSN 1552-3365. PMID 23548806. S2CID 27181307.

- Philippon, Marc J.; Briggs, Karen K.; Hay, Connor J.; Kuppersmith, David A.; Dewing, Christopher B.; Huang, Michael J. (June 2010). "Arthroscopic labral reconstruction in the hip using iliotibial band autograft: technique and early outcomes". Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 26 (6): 750–756. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2009.10.016. ISSN 1526-3231. PMID 20511032.

- Domb, Benjamin G.; El Bitar, Youssef F.; Stake, Christine E.; Trenga, Anthony P.; Jackson, Timothy J.; Lindner, Dror (January 2014). "Arthroscopic labral reconstruction is superior to segmental resection for irreparable labral tears in the hip: a matched-pair controlled study with minimum 2-year follow-up". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 42 (1): 122–130. doi:10.1177/0363546513508256. ISSN 1552-3365. PMID 24186974. S2CID 206528292.

- Philippon, Marc J.; Nepple, Jeffrey J.; Campbell, Kevin J.; Dornan, Grant J.; Jansson, Kyle S.; LaPrade, Robert F.; Wijdicks, Coen A. (2014-04-01). "The hip fluid seal—Part I: the effect of an acetabular labral tear, repair, resection, and reconstruction on hip fluid pressurization". Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 22 (4): 722–729. doi:10.1007/s00167-014-2874-z. ISSN 0942-2056. PMID 24519614. S2CID 8109881.

- Nepple, Jeffrey J.; Philippon, Marc J.; Campbell, Kevin J.; Dornan, Grant J.; Jansson, Kyle S.; LaPrade, Robert F.; Wijdicks, Coen A. (2014-04-01). "The hip fluid seal—Part II: The effect of an acetabular labral tear, repair, resection, and reconstruction on hip stability to distraction". Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 22 (4): 730–736. doi:10.1007/s00167-014-2875-y. ISSN 0942-2056. PMID 24509878. S2CID 9258547.

- Haversath, M.; Hanke, J.; Landgraeber, S.; Herten, M.; Zilkens, C.; Krauspe, R.; Jäger, M. (June 2013). "The distribution of nociceptive innervation in the painful hip: a histological investigation". The Bone & Joint Journal. 95-B (6): 770–776. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.95B6.30262. ISSN 2049-4408. PMID 23723270.

- Botser, Itamar B.; Smith, Thomas W.; Nasser, Rima; Domb, Benjamin G. (2011). "Open Surgical Dislocation Versus Arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement: A Comparison of Clinical Outcomes". Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 27 (2): 270–278. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2010.11.008. PMID 21266277.

- Ng, Vincent Y.; Arora, Naveen; Best, Thomas M.; Pan, Xueliang; Ellis, Thomas J. (November 2010). "Efficacy of surgery for femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 38 (11): 2337–2345. doi:10.1177/0363546510365530. ISSN 1552-3365. PMID 20489213. S2CID 41692112.

- Kivlan, Benjamin R.; Nho, Shane J.; Christoforetti, John J.; Ellis, Thomas J.; Matsuda, Dean K.; Salvo, John P.; Wolff, Andrew B.; Van Thiel, Geoffrey S.; Stubbs, Allston J. (January–February 2017). "Multicenter Outcomes After Hip Arthroscopy: Epidemiology (MASH Study Group). What Are We Seeing in the Office, and Who Are We Choosing to Treat?". American Journal of Orthopedics (Belle Mead, N.J.). 46 (1): 35–41. ISSN 1934-3418. PMID 28235111.

- Wolff, Andrew B.; Grossman, Jamie (July 2016). "Management of the Acetabular Labrum". Clinics in Sports Medicine. 35 (3): 345–360. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2016.02.004. ISSN 1556-228X. PMID 27343389.

- White, Brian J.; Herzog, Mackenzie M. (February 2016). "Arthroscopic Labral Reconstruction of the Hip Using Iliotibial Band Allograft and Front-to-Back Fixation Technique". Arthroscopy Techniques. 5 (1): e89–97. doi:10.1016/j.eats.2015.08.009. ISSN 2212-6287. PMC 4809662. PMID 27073784.

- White, Brian J.; Patterson, Julie; Herzog, Mackenzie M. (February 2018). "Bilateral Hip Arthroscopy: Direct Comparison of Primary Acetabular Labral Repair and Primary Acetabular Labral Reconstruction". Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 34 (2): 433–440. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2017.08.240. ISSN 1526-3231. PMID 29100774.

- Boykin, Robert E.; Patterson, Diana; Briggs, Karen K.; Dee, Ashley; Philippon, Marc J. (October 2013). "Results of arthroscopic labral reconstruction of the hip in elite athletes". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 41 (10): 2296–2301. doi:10.1177/0363546513498058. ISSN 1552-3365. PMID 23928321. S2CID 7843955.

- Ilizaliturri, Victor M. (March 2009). "Complications of arthroscopic femoroacetabular impingement treatment: a review". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 467 (3): 760–768. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0618-4. ISSN 1528-1132. PMC 2635434. PMID 19018604.