Nursing Madonna

The Nursing Madonna, Virgo Lactans, or Madonna Lactans, is an iconography of the Madonna and Child in which the Virgin Mary is shown breastfeeding the infant Jesus. In Italian it is called the Madonna del Latte ("Madonna of milk"). It was a common type in painting until the change in atmosphere after the Council of Trent, in which it was rather discouraged by the church, at least in public contexts, on grounds of propriety.[1]

The depiction is mentioned by Pope Gregory the Great, and a mosaic depiction probably of the 12th century is on the facade of Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome, though few other examples survive from before the late Middle Ages. It continued to be found in Orthodox icons (as Galaktotrophousa in Greek, Mlekopitatelnitsa in Russian), especially in Russia.[2]

Usage of the depiction seems to have revived with the Cistercian Order in the 12th century, as part of the general upsurge in Marian theology and devotion. Milk was seen as "processed blood", and the milk of the Virgin to some extent paralleled the role of the Blood of Christ.[3][4]

In the Middle Ages, the middle and upper classes usually contracted breastfeeding out to wetnurses, and the depiction of the Nursing Madonna was linked with the Madonna of Humility, a depiction that showed the Virgin in more ordinary clothes than the royal robes shown, for instance, in images of the Coronation of the Virgin, and often seated on the ground. The first half of the 13th century produced more than one hundred surviving paintings.[5] The appearance of such paintings in Tuscany in the early 14th century was something of a visual revolution, partly replacing Queen of Heaven depictions; they were also popular in Iberia.

Late Middle Ages and decline

.JPG.webp)

Most late medieval paintings are smaller devotional panels containing only the two essential figures (sometimes plus small angels). But the nursing Virgin is sometimes the centre of a sacra conversazione with saints, and perhaps donor portraits.

In Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting, especially in Antwerp, variants of the newly-popular subject of the Holy Family (a Virgin and Child with Saint Joseph) with a breastfeeding Virgin appeared in the early 16th century; Joos van Cleve painted many of these. These were on small devotional panels for the homes of the prosperous rather than churches. Several compositions were copied by different artists, probably done from drawings passed around.[6] Drawing on a passage by Ludolph of Saxony, the subject could also be turned into a Rest on the Flight into Egypt, with the attraction of a landscape background. Joseph might be shown close to Mary, or as a small figure foraging in the background, as Gerard David's painting does.[7] Sometimes the Virgin is breastfeeding while riding on the back of the ass, as early as a 12th-century miniature in Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai.[8]

Another composition from the same Flemish milieu, mostly found on the cheaper support of linen rather than panel, appears to have been connected with devotions to the Immaculate Conception. This just shows a Virgin, looking down, and Child.[9]

Another type of depiction, also deprecated after Trent, showed Mary baring her breast in a traditional gesture of female supplication to Christ when asking for mercy for sinners in Deesis or Last Judgement scenes. A good example is the fresco at S. Agostino in San Gimignano, by Benozzo Gozzoli, painted to celebrate the end of the plague.

The nursing Virgin survived into the Baroque; examples include some depictions of the Holy Family, by El Greco for example,[10] and narrative scenes such as the Rest on the Flight into Egypt, for example by Orazio Gentileschi (versions in Birmingham and Vienna).

Lactatio Bernardi

A variant, known as the Lactation of St Bernard (Lactatio Bernardi in Latin, or simply Lactatio) is based on a miracle or vision concerning St Bernard of Clairvaux where the Virgin sprinkled milk on his lips (in some versions he is awake, praying before an image of the Madonna, in others asleep).[11] In art he usually kneels before a Madonna Lactans, and as Jesus takes a break from feeding, the Virgin squeezes her breast and he is hit with a squirt of milk, often shown travelling an impressive distance. The milk was variously said to have given him wisdom, shown that the Virgin was his mother (and that of mankind generally), or cured an eye infection. In this form the Nursing Madonna survived into Baroque art, and sometimes the Rococo, as in the high altar at Kloster Aldersbach.[12]

Gallery

Master of the Magdalen, with Saints Leonard and Peter and Scenes from the Life of Saint Peter, c. 1270

Master of the Magdalen, with Saints Leonard and Peter and Scenes from the Life of Saint Peter, c. 1270%252C_madonna_del_latte%252C_1340-50_ca.JPG.webp) Lippo Memmi or circle, c. 1340–50

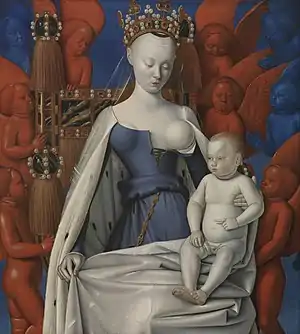

Lippo Memmi or circle, c. 1340–50 Right wing of the Melun Diptych, c. 1452, Jean Fouquet

Right wing of the Melun Diptych, c. 1452, Jean Fouquet Nursing Madonna (ca. 1500 or after), by Jan Provoost

Nursing Madonna (ca. 1500 or after), by Jan Provoost Andrea Solario, Madonna of the Green Cushion, c. 1507–10

Andrea Solario, Madonna of the Green Cushion, c. 1507–10 Holy Family, Joos van Cleve, c. 1512–13

Holy Family, Joos van Cleve, c. 1512–13 During the Flight into Egypt, André Gonçalves, Portugal, before 1755

During the Flight into Egypt, André Gonçalves, Portugal, before 1755 Galaktotrophousa Makarios, Greece c. 1784

Galaktotrophousa Makarios, Greece c. 1784

See also

- Madonna Litta

- Chapel of the Milk Grotto, Bethlehem

References

- Hinsdale, Mary Ann; Dugan, Kate; Owens, Jennifer (2009). From the Pews in the Back. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8146-3258-1.

- Tradigo, Alfredo (2006). Icons And Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church, A Guide to Imagery. Getty. p. 183. ISBN 9780892368457.

- Saxon, Elizabeth (2006). The Eucharist in Romanesque France: Iconography And Theology. Boydell. pp. 205–207. ISBN 9781843832560.

- Ainsworth, 308-310

- Ashton, Anne M. (2006). "One-Maria lactans". Interpreting breast iconography in Italian art, 1259-1609 (PDF). Università of St Andrews. p. 42. OCLC 809064950. Retrieved April 21, 2021. (PhD dissertazione)

- Ainsworth, 246-252

- Ainsworth, 308

- [[:File:Flight into Egypt (12 Sinai).jpg| Saint Catherine's Monastery]]

- Ainsworth, 252-254

- El Greco in Budapest

- Dewez, Léon; van Iterson, Albert (1956). "La lactation de saint Bernard: Legende et iconographie". Citeaux in de Nederlanden. 7: 165–89.

- File:Aldersbach Pfarrkirche - Hochaltar 2 Altarbild.jpg

Sources

- Ainsworth, Maryan Wynn et al., From Van Eyck to Bruegel: Early Netherlandish Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009. ISBN 0-8709-9870-6, google books