Lagetta lagetto

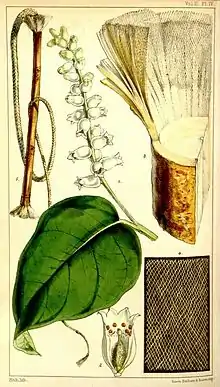

Lagetta lagetto is a species of tree native to several Caribbean islands. It is called the lacebark or gauze tree because the inner bark is structured as a fine netting that has been used for centuries to make clothing as well as utilitarian objects like rope.[1]

| Lacebark tree | |

|---|---|

_pl._4502_(1850).jpg.webp) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malvales |

| Family: | Thymelaeaceae |

| Genus: | Lagetta |

| Species: | L. lagetto |

| Binomial name | |

| Lagetta lagetto | |

Taxonomy

Lagetta lagetto, the lacebark (sometimes: lace-bark) or gauze tree, is native to the islands of Jamaica, Cuba, and Hispaniola (in both Haiti and the Dominican Republic).[2] It was formerly known as L. lintearia.[3] It is best documented on Jamaica, although few specimens have been reported in recent decades, and it has not been collected at all on Cuba in recent years.[4] It gets its genus and current species name from its alternate common name of lagetto (a corruption of the Spanish word latigo, or whip) on Jamaica.[1][5][6] It is known as laget à dentelle or bois dentelle on Haiti and daguilla or guanilla in the Dominican Republic and Cuba. It is also known in one part of western Jamaica as white bark.[1]

Lagetta lagetto is the most widespread of the three known species of the genus Lagetta.[7] The two other species of Lagetta are both native to Cuba: L. valenzuelana, the Valenzuela lacebark tree, and L. wrightiana, the Wright lacebark tree.[2] Little is known about either species.

Lagetta is not the only member of the family Thymelaeaceae to be used as a fiber source; others include Daphne species and Edgeworthia chrysantha, both of which supply fiber for papermaking.

Description and habitat

Lagetta lagetto is a small, narrow, pyramidal tree, growing between 12 and 40 feet (3.7 and 12.2 m) tall.[1] It has a straight trunk with a rough outer bark.[8] It forms part of the subcanopy of the Caribbean forest, sprouting from crevices of rocky limestone slopes.[1] It has been recorded all along the central spine of Jamaica at altitudes of from 1,400 to 2,700 feet (430 to 820 m) as well as along other mountainous ridges in the west central parts of the island.[1][9]

The lacebark tree has smooth, dark green, leathery, somewhat heart-shaped evergreen leaves, roughly 4 inches (10 cm) long by 2.5 inches wide.[8] The small, white, tubular-bell-shaped flowers are produced as racemes in a pattern of alternating flower-stalks along the branchlets. There is no calyx, but the corolla divides into four points at its outer tip.[8] There are eight short filamentous stamens concealed within the flower.[8] It produces a roundish, hairy drupe inside of which is a dark-brown, ovoid kernel about one-quarter inch long.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, L. lagetto was reported to be abundant and widespread in Jamaica.[9] By the late 19th century, however, there are reports of growing scarcity attributed to overharvesting without replanting. It is now rare, probably in large part due to such overexploitation combined with more general loss of forest lands in the same period.[1][9] It is not reported to have been actively cultivated, but if it ever was, there may also have been loss of specialized knowledge of its cultivation needs.[9] In the late 19th and early 20th century, L. lagetto was often grown in botanic gardens[5] in such countries as Great Britain, the United States, and Australia, but no known specimens are found in botanic gardens today.[9]

Loma Daguilla, an isolated mountain near San Juan, Cuba, is named for the tree, which is known locally as daguilla de loma and has been abundant thereabouts.[10]

Uses

The inner bark of Lagetta species—the phloem layer that carries nutrients from the leaves to the roots—consists of twenty to thirty tough, thin, dense layers of interlacing bast fibers.[5][8] Whereas in most economically important fibrous plants the bast fibers are formed in straight, parallel lines, in the Lagetta species they separate and rejoin to form a fine natural net or mesh of tiny rhomboids.[11] The lacebark tree's layers of inner bark can be carefully pulled apart to produce multiple sheets of white netting known eponymously as lacebark.[9] Lacebark is thus unique among other tropical barkcloths in being produced without having to be beaten into shape.[1]

Although the main steps of lacebark production are clear—detaching the entire bark from the tree, extracting the inner bark, and pulling apart the layers—the details of the process are not well documented. The naturalist Philip Gosse supplied a general account of lacebark tree harvesting from a stopover in Haiti in 1846,[9] while contemporary accounts by Emily Brennan, Mark Nesbitt, and others rely in large part on oral accounts from the few remaining lacebark harvesters.[1][9] It appears that lacebark was sourced from trees growing wild (rather than under cultivation), and though sometimes an entire tree would be felled to get at the bark, in many cases a single branch would be lopped off to preserve the tree for further harvesting. Ordinarily, lacebark's corky outer bark could be readily removed by hand. If the lacebark dried out too much during the process of extraction, it would be soaked or boiled in water to restore flexibility, a process that also softened the lacebark by removing some naturally stiffening substances.[1][9] The extracted netting would be stretched out—expanding the textile to at least five times its original width[1]—and then bleached to a bright white through sun-drying.[9] In Jamaica, harvesting was mainly carried out by men, while production of objects from lacebark was the prerogative of women.

As a textile, lacebark is soft and may be readily dyed or stained.[1] In 1883, the French naturalist Félix-Archimède Pouchet wrote that lacebark was "as fine as our muslin and even takes its place in the toilet of our ladies".[12] Veils, shawls, dresses, aprons, caps, collars, frills, slippers, purses, and other clothing and accessories have been made of the fiber, mainly in the period from the late 17th to the late 19th centuries. There is evidence that it was routinely used in clothing worn by people from all ranks of society in Jamaica.[9] The survival of a number of objects that are well over a hundred years old testifies to lacebark's durability as a material. Collections with lacebark items include Kew Gardens, the Pitt Rivers Museum and Victoria and Albert Museum (U.K.), the Field Museum (U.S.), the Museum of Vancouver (Canada), and the Institute of Jamaica in Kingston.[1] At least two monarchs of Great Britain have been given lacebark clothing: King Charles II, who received a cravat and ruffles of lacebark from Sir Thomas Lynch,[8] then governor of Jamaica, and Queen Victoria, who was presented with a lacebark dress at the 1851 Great Exhibition.[11]

Lacebark has also been used in the manufacture of utilitarian items such as curtains, hammocks, rope, bridles, and whips.[5] In the case of whips, the handle was usually made from a narrow tree branch with the outer bark still attached, while the whip tail was made from twisted or braided strands of lacebark extruding from the same branch.[1] Lacebark whips were commonly used to punish slaves on Jamaica in the era before the abolition of slavery in 1833–34.[1]

The second half of the 19th century saw numerous appearances of lacebark items in industrial exhibitions, possibly because the British perceived a potential for expanded production in Jamaica.[9] There were also some experiments in making paper out of lacebark.[1] However, commercial-scale production never took off, and by the 1880s, most lacebark appears to have been shifted into the creation of tourist souvenirs such as doilies, fans, and ornamental whips.[9] One travel writer referred to these souvenirs as works of art that "exhibit refined taste and excellent workmanship."[13] Objects such as fans sometimes had a lacebark substrate to which dried specimens of local flora were attached.[1][4][13] Production of lacebark items (even as souvenirs) started tailing off in the early 20th century, largely because of the increasing rarity of the trees but also partly because of the labor-intensive nature of harvesting work and (after World War II) a decline of interest in traditional crafts.[1] Lacebark crafts had nearly vanished by the 1960s, and an attempted revival in the 1980s sputtered out for a variety of reasons, among them the continuing threats to lacebark habitat that made it difficult to establish reliable supply chains.[1][9]

Lacebark is less well known than other textiles made from plant fibers, such as tapa cloth. It is uncertain whether the Taino Amerindians, the former inhabitants of the Caribbean islands to which the genus Lagetta is native, ever made lacebark.[9] It has been suggested that the tree's use for textiles may have followed the arrival of slaves from West Africa, where there is a long tradition of barkcloth.[9] Lacebark appears early in European writing about Jamaica; for example, Sir Hans Sloane mentions it in his account of a trip to the island in the 1680s.

- "What is most strange in this Tree is, that the inward bark is made up of about twelve Coats, Layers, or Tunicles, appearing white and solid, which if cut off for some Length, clear'd of its outward Cuticula, or Bark, and extended by the Fingers, the Filaments or Threads thereof leaving some rhomboidal Interstices, greater or smaller according to the Dimensions you extend it to, form a Web not unlike Gause, Lace, or thin Muslin."[14]

See also

References

- Brennan, Emily, Lori-Ann Harris, and Mark Nesbitt. "Object Lesson: Jamaican Lace-Bark: Its History and Uncertain Future". Textile History 44:2 (November 2013), pp. 235–253.

- Grandtner, M.M. Elsevier's Dictionary of Trees. Vol. 1. Elsevier Science, 2005.

- Steeve O. Buckridge (2016-07-14). African Lace-bark in the Caribbean: The Construction of Race, Class and Gender. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-4725-6930-1.

- Pearman, G. and Prendergast, H.D.V. "Plant Portraits: Items from the Lacebark Tree [Lagetta lagetto (W. Wright) Nash; Thymelaeaceae] from the Caribbean" Archived 2015-07-24 at the Wayback Machine. Economic Botany 54(1), New York Botanical Garden Press, 2000, pp. 4–6.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Gerard, W. R. "Origin of the word Lagetto". American Anthropologist, vol. xiv (1912), p. 404.

- Grandtner lists only three species, while Pearman and Prendergast mention four without specifying their names.

- W. T. M., "The Lace Bark, or Gauze Tree". The Technologist: A Monthly Record of Science Applied to Art and Manufacture., vol. 1. London: Kent & Co., Paternoster Row, 1861, pp. 254–55.

- Brennan, Emily, and Mark Nesbitt. "Is Jamaican Lace-Bark (Lagetta lagetto) a Sustainable Material?". Text: For the Study of Textile Art, Design and History, vol. 38, 2010-11., pp 17–23.

- Holland, W.J., ed. "Contributions to the Natural History of the Isle of Pines, Cuba". Board of Trustees of the Carnegie Institute, 1917.

- Earnshaw, Pat. A Dictionary of Lace. Courier Corporation, 1999.

- Pouchet, Félix-Archimède. The Universe, or, the Wonders of Creation. Portland, Maine: H. Hallett & Co., 1883.

- Leader, Alfred. Through Jamaica with a Kodak. Bristol, U.K.: John Wright & Co., 1907.

- Sloane, H. A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica. Vol. 11. Printed for the Author, 1725.