Lagosuchus

Lagosuchus is an extinct genus of avemetatarsalian archosaur from the Late Triassic of Argentina. The type species of Lagosuchus, Lagosuchus talampayensis, is based on a small partial skeleton recovered from the early Carnian-age Chañares Formation. The holotype skeleton of L. talampayensis is fairly fragmentary, but it does possess some traits suggesting that Lagosuchus was a probable dinosauriform, closely related to dinosaurs.[1][2][3]

| Lagosuchus Temporal range: Late Triassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

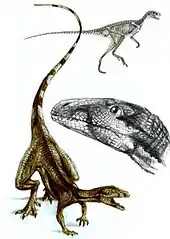

| Mounted skeleton (based on specimens previously referred to Marasuchus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Ornithodira |

| Clade: | Dinosauromorpha |

| Order: | †Lagosuchia Paul, 1988 |

| Family: | †Lagosuchidae Bonaparte, 1975 |

| Genus: | †Lagosuchus Romer, 1971 |

| Species: | †L. talampayensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Lagosuchus talampayensis Romer, 1971 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

A second potential species of Lagosuchus, L. lilloensis, is based on an assortment of slightly larger and more well-preserved fossils.[4] These larger specimens have been considered much more diagnostic and informative than the original small L. talampayensis skeleton. As a result, some paleontologists have placed the larger specimens into a new genus, Marasuchus. Marasuchus is generally considered one of the more complete early dinosauriforms, useful for estimating ancestral traits for the origin of dinosaurs. This would also render Lagosuchus a nomen dubium, simply a name referring to a fossil which is too fragmentary to have a formal genus.[2][5] However, other paleontologists support the argument that Lagosuchus is a valid genus, and that Marasuchus is a junior synonym of it.[6][3]

History

The type species Lagosuchus talampayensis was first described by Alfred S. Romer in 1971, who considered it a "pseudosuchian" (then a collection of various non-dinosaurian "thecodonts").[1] In 1972 he named a second species, Lagosuchus lilloensis, known from larger and more well-preserved specimens.[4] A later review by Jose Bonaparte in 1975 synonymized the two species and considered Lagosuchus intermediate between "pseudosuchians" and saurischian dinosaurs.[6]

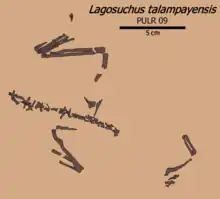

Modern authors now consider at least L. lilloensis to be firmly on the lineage of archosaurs leading to dinosaurs.[5] However, the genus Lagosuchus is regarded by some to be dubious. Paul Sereno and Andrea Arcucci considered L. talampayensis to be undiagnosable in a 1994 study, and reclassified L. lilloensis as a new genus, Marasuchus.[2] In 2019, PULR 09, the holotype skeleton of L. talampayensis, was redescribed by Federico Agnolin and Martin Ezcurra. They argued that the skeleton was not only diagnostic, but indistinguishable from specimens of Marasuchus lilloensis. As a result, they supported the synonymy proposed by Bonaparte, referring specimens of Marasuchus lilloensis back to Lagosuchus talampayensis.[3]

The Chañares Formation's age has been through much debate. It has traditionally been considered to belong to the Ladinian stage, the last stage of the Middle Triassic. Radiometric dating in 2016 has dated the main fossiliferous section of the formation to the early Carnian stage, near the start of the Late Triassic.[7]

Description

Lagosuchus talampayensis, in its most restricted form, can only be described based on the incomplete holotype skeleton. It was a lightly built archosaur, with long, slender legs and well-developed feet - features it shares with certain dinosaurs.[8] With its short forelimbs, long shin bones, and narrow stance, it was likely an agile biped adapted for running.[1] Gregory S. Paul inferred that Lagosuchus was one of the smallest Triassic archosaurs, with a weight of about 167 g, similar in size and ecology to a weasel or ferret.[9] Thomas Holtz estimated that Lagosuchus could have obtained a total length of 1.7 ft (51 cm) and a weight similar to that of a pigeon (50-500 g).[10] However, these estimates may have been based on specimens referred to Marasuchus, some of which were significantly larger than the Lagosuchus holotype.[4]

Vertebrae and forelimbs

The dorsal (trunk) vertebrae had centra about three times longer than tall, slightly more elongated than those referred to Marasuchus. Yet the dorsals also had many traits in common with Marasuchus, such as large excavations below the transverse processes. In addition, they both have trapezoidal neural spines with thickened upper edges which expand forwards and backwards to contact those of adjacent vertebrae. The contemporary silesaurid Lewisuchus has a similar neural spine morphology, but it possesses osteoderms on its neural spines, unlike Lagosuchus and Marasuchus. The two sacral (hip) vertebrae had large and slightly tapering transverse processes. This is also the case for the first four caudal (tail) vertebrae at the base of the tail. Further back, the caudals have much shorter transverse processes and more elongated centra, like those of Marasuchus.[3]

The scapula (shoulder blade) was narrow, with a slightly expanded upper tip and a thick longitudinal ridge on its inner surface. The humerus was also quite narrow, with a subtriangular deltopectoral crest in its upper part. The deltopectoral crest extends about 31% down the length of the humerus, making it somewhat less extensive than that of other avemetatarsalians (including Marasuchus). The radius and ulna are thin, simple, and unusually short, only about 65% the length of the humerus. In contrast, Marasuchus has a larger ulna with a strong olecranon process.[3] The forelimbs in general were much smaller than the hindlimbs.[1]

Hip and hindlimbs

The pelvis (hip) is similar to that of Marasuchus, with a thin pubis and a plate-like ischium which has a large ridge on its rear edge. The femur is elongated and has a slightly inturned femoral head. The femoral head is characteristically ‘globose’, with a strong projecting convex surface stretching up along its inner and upper portions. This trait is shared with Marasuchus and lagerpetids. The femur also possessed a knob-like anterior trochanter and a distinct fourth trochanter. The tibia and fibula were narrow and about 10% longer than the femur. Like other dinosauriforms, the tibia had a strong cnemial crest at the knee and a lateral groove near the ankle. The ankle has a small distal tarsal 3, a larger distal tarsal 4, and a rounded astragalus, but the calcaneum is missing from the fossil. The middle three metatarsals are elongated, with metatarsal III as the longest. Metatarsal V is short and tapers to a sharp tip. Metatarsal I is also short, though still longer than V (unlike Marasuchus). Phalanges are slender, and an isolated pedal ungual (toe claw) is weakly curved and flattened sideways.[3]

Palaeobiology

Metabolism

It is believed that Lagosuchus and Marasuchus were transitional between cold blooded reptiles and warm blooded dinosaurs.[11]

References

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood (15 June 1971). "The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. X. Two new but incompletely known long-limbed pseudosuchians". Breviora. 378: 1–10.

- Sereno, Paul C.; Arcucci, Andrea B. (March 1994). "Dinosaurian precursors from the Middle Triassic of Argentina: Marasuchus lilloensis, gen. nov". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 14 (1): 53–73. doi:10.1080/02724634.1994.10011538.

- Agnolin, Federico L.; Ezcurra, Martin D. (2019). "The Validity of Lagosuchus Talampayensis Romer, 1971 (Archosauria, Dinosauriformes), from the Late Triassic of Argentina" (PDF). Breviora. 565 (1): 1–21. doi:10.3099/0006-9698-565.1.1. ISSN 0006-9698. S2CID 201949710.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood (11 August 1972). "The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XV. Further remains of the thecodonts Lagerpeton and Lagosuchus". Breviora. 394: 1–7.

- Nesbitt, S.J. (2011). "The Early Evolution of Archosaurs: Relationships and the Origin of Major Clades". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 352: 189. doi:10.1206/352.1. hdl:2246/6112. ISSN 0003-0090. S2CID 83493714.

- Jose, Bonaparte (1975). "Nuevos materiales de Lagosuchus talampayensis Romer (Thecodontia-Pseudosuchia) y su significado en el origen de los Saurischia: Chañarense inferior, Triásico medio de Argentina" (PDF). Acta Geológica Lilloana. 13 (1): 5–90.

- Claudia A. Marsicano; Randall B. Irmis; Adriana C. Mancuso; Roland Mundil; Farid Chemale (2016). "The precise temporal calibration of dinosaur origins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (3): 509–513. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113..509M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1512541112. PMC 4725541. PMID 26644579.

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-84028-152-1.

- Paul, Gregory (1988). Predatory dinosaurs of the world. Simon & Schuster.

- Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix.

- Pontzer, Herman; Allen, Vivian; Hutchinson, John R. (2009). "Biomechanics of Running Indicates Endothermy in Bipedal Dinosaurs". PLOS ONE. 4 (12): e7783. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7783P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007783. PMC 2772121. PMID 19911059.