Lake Burley Griffin

Lake Burley Griffin is an artificial lake in the centre of Canberra, the capital of Australia. It was completed in 1963 after the Molonglo River, which ran between the city centre and Parliamentary Triangle, was dammed. It is named after Walter Burley Griffin, the American architect who won the competition to design the city of Canberra.[2]

| Lake Burley Griffin | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Lake Burley Griffin viewed from Black Mountain Tower | |

Lake Burley Griffin  Lake Burley Griffin | |

| Location | Canberra, Australian Capital Territory () |

| Coordinates | 35°17′36″S 149°06′50″E |

| Lake type | Artificial lake |

| Primary inflows | Molonglo River, Sullivans Creek, Jerrabomberra Creek |

| Primary outflows | Molonglo River |

| Catchment area | 183.5 km2 (70.8 sq mi)[1] |

| Basin countries | Australia |

| Max. length | 11 km (6.8 mi) |

| Max. width | 1.2 km (0.75 mi) |

| Surface area | 6.64 km2 (2.56 sq mi; 1,640 acres) |

| Average depth | 4 m (13 ft) |

| Max. depth | 18 m (59 ft) |

| Water volume | 33,000,000 m3 (1.2×109 cu ft; 33 GL) |

| Surface elevation | 556 m (1,824 ft) |

| Dam | Scrivener Dam |

| Islands | 6 (Queen Elizabeth II, Springbank, Spinnaker, others unnamed) |

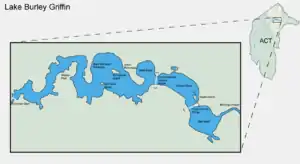

| Sections/sub-basins | East Basin, Central Basin, West Basin, West Lake and Tarcoola Reach, Yarramundi Reach |

| Settlements | Canberra |

Griffin designed the lake with many geometric motifs, so that the axes of his design lined up with natural geographical landmarks in the area. However, government authorities changed his original plans, and no substantial work was completed before he left Australia in 1920. Griffin's proposal was further delayed by the Great Depression and World War II, and it was not until the 1950s that planning resumed. After political disputes and consideration of other proposed variations, excavation work began in 1960 with the energetic backing of Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies. After the completion of the bridges and dams, the dams were locked in September 1963. However, because of a drought, the lake's target water level was not reached until April 1964. The lake was formally inaugurated on 17 October 1964.

The lake is located in the approximate geographic centre of the city, and it is the centrepiece of the capital in accordance with Griffin's original designs. Numerous important institutions, such as the National Gallery, National Museum, National Library, Australian National University and the High Court were built on its shores, and Parliament House is a short distance away. Its surrounds, consisting mainly of parklands, are popular with recreational users, particularly in the warmer months. Though swimming in the lake is uncommon, it is used for a wide variety of other activities, such as rowing, fishing, and sailing.

The lake is an ornamental body with a length of 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) and a width, at its widest, of 1.2 kilometres (0.75 mi). It has an average depth of 4 metres (13 ft) and a maximum depth of about 18 metres (59 ft) near the Scrivener Dam. Its flow is regulated by the 33-metre-tall (108 ft) Scrivener Dam, designed to handle floods that occur once in 5,000 years. In times of drought, water levels can be maintained through the release of water from Googong Dam, located on an upstream tributary of the Molonglo River.

Design history

Charles Robert Scrivener (1855–1923) recommended the site for Canberra in 1909, which was to be a planned capital city for the country. One of the reasons for the location's selection was its ability to store water "for ornamental purposes at reasonable cost";[3] Scrivener's work had demonstrated that the topography could be used to create a lake through flooding.[4]

In 1911, a competition for the design of Canberra was launched, and Scrivener's detailed survey of the area was supplied to the competing architects.[3] The Molonglo River flowed through the site, which was a flood plain[5] and Scrivener's survey showed in grey an area clearly representing an artificial lake—similar to the lake later created—and four possible locations for a dam to create it.[6][7] Most of the proposals took the hint and included artificial bodies of water.[3]

Walter Burley Griffin's design

The American architect Walter Burley Griffin won the contest and was invited to Australia to oversee the construction of the nation's new capital after the judges' decision was ratified by King O'Malley, the Minister for Home Affairs.[4][8] Griffin's proposal, which had an abundance of geometric patterns, incorporated concentric hexagonal and octagonal streets emanating from several radii.[9]

His lake design was at the heart of the city and consisted of a Central Basin in the shape of circular segment, a West and East Basin, which were both approximately circular, and a West and East Lake, which were much larger and irregularly shaped, at either side of the system.[10] The East Lake was supposed to be 6 metres (20 ft) higher than the remaining components.[11] Griffin's proposal was "the grandest scheme submitted, yet it had an appealing simplicity and clarity.[4]

The lakes were deliberately designed so that their orientation was related to various topographical landmarks in Canberra.[3][12] The lakes stretched from east to west and divided the city in two; a land axis perpendicular to the central basin stretched from Capital Hill—the future location of the new Parliament House on a mound on the southern side—north northeast across the central basin to the northern banks along Anzac Parade to the Australian War Memorial (although a casino was originally planned in its place).[13] This was designed so that looking from Capital Hill, the War Memorial stood directly at the foot of Mount Ainslie. At the southwestern end of the land axis was Bimberi Peak.[12]

The straight edge of the circular segment that formed the central basin was designated the water axis, and it extended northwest towards Black Mountain.[12] A line parallel to the water axis, on the northern side of the city, was designated the municipal axis.[14] The municipal axis became the location of Constitution Avenue, which linked City Hill in Civic Centre and Market Centre. Commonwealth Avenue and Kings Avenue were to run from the southern side from Capital Hill to City Hill and Market Centre on the north respectively, and they formed the western and eastern edges of the central basin. The area enclosed by the three avenues was known as the Parliamentary Triangle, and was to form the centrepiece of Griffin's work.[14]

Later, Scrivener, as part of a government design committee, was responsible for modifying Griffin's winning design.[4][15][16] He recommended changing the shape of the lake from Griffin's very geometric shapes to a much more organic one using a single dam, unlike Griffin's series of weirs.[4][17] Griffin lobbied for the retention of the pure geometry, saying that they were "one of the reasons d'etre of the ornamental waters", but he was overruled.[18] The new design included elements from several of the best design submissions and was widely criticised as being ugly. The new plan for the lake retained Griffin's three formal basins: east, central, and west, though in a more relaxed form.[2][17]

Griffin entered into correspondence with the government over the plan and its alternatives, and he was invited to Canberra to discuss the matter.[19] Griffin arrived in August 1913 and was appointed Federal Capital Director of Design and Construction for three years.[4][20]

The plans were varied again in the following years, but the design of Lake Burley Griffin remained based largely on the original committee's plan.[21] It was later gazetted and legally protected by the federal parliament in 1926,[22] based on a 1918 plan.[11] However, Griffin had a strained working relationship with the Australian authorities and a lack of federal government funding meant that by the time he left in 1920, little significant work had been done on the city.[8][21] A 1920s proposal to reduce West Lake into a ribbon of water was made on the basis of flood safety. However, the Owen and Peake report of 1929 ruled that the original design was hydrologically sound.[11]

Political disputes and modifications

With the onset of the Great Depression, followed by World War II, development of the new capital was slow,[23] and in the decade after the end of the war, Canberra was criticised for resembling a village,[13][23] and its disorganised collection of buildings was deemed ugly.[24] Canberra was often derisively described as "several suburbs in search of a city".[25]

During this time, the Molonglo River flowed through the flood basin, with only a small fraction of the water envisaged in Griffin's plan.[26] The centre of his capital city consisted of mostly farmland, with small settlements—mostly wooden, temporary and ad hoc—on either side.[27] There was little evidence that Canberra was planned,[13] and the lake and Parliamentary Triangle at the heart of Griffin's plan was but a paddock.[13] Royal Canberra Golf Course, and Acton Racecourse and a sports ground were located on the pastoral land that was to become the West Lake, and people had to disperse the livestock before playing sport.[13] A rubbish dump stood on the northern banks of the location of central basin,[28] and no earth had been moved since Griffin's departure three decades earlier.[29]

In 1950, the East Lake—the largest component—was eliminated upon the advice of the National Capital Planning and Development Committee (NCPDC).[30] Today, what would have been the East Lake corresponds to the suburb of Fyshwick. The rationale given was that around 1,700 acres (690 ha) of farmland would be submerged and that the Molonglo would have insufficient water to keep the lake filled.[30]

In 1953, the NCPDC excised the West Lake from its plans and replaced it with a winding stream,[31] which was 110 metres (360 ft) wide and covered around a fifth of the original area.[32] As the NCPDC had only advisory powers, this change was attributed to the influence of senior officials in the Department of the Interior who felt that Griffin's plan was too grandiose.[33] Advocates of watered-down scheme thought it was more economical and saved 350 hectares (860 acres) of land for development.[32] However, according to engineering reports that were ignored, the smaller plan would actually cost more money and require a more complicated structure of dams that would in any case be less able to prevent flooding.[34][35]

Initially, there was little opposition during the consultation period before the alterations were made.[32] However, opposition to the reduction of the water area grew.[31] The process that resulted in the alteration was criticised for being non-transparent and sneaky.[36] Some organisations complained that they were not given an opportunity to express their opinion before the change was gazetted,[37] and many politicians and the chief town planner were not informed.[38] Critics bitterly insinuated that politically influential members of the Royal Canberra Golf Club, whose course was situated on the location of the proposed West Lake, were responsible for the change in policy.[39]

The Parliamentary Public Works Committee advised the Parliament to restore the West Lake.[31] After an inquiry in late 1954, it concluded that:

The West Lake is desirable and practicable. It was eliminated from the Canberra plan by the Department of the Interior without adequate investigation by the National Capital Planning and Development Committee and replaced by a ribbon of water scheme involving a capitalised cost or nearly 3 million more. The lake should be restored to the plan, and the necessary Ministerial action is recommended as soon as possible.[40]

The Prime Minister, Robert Menzies,[41] regarded the state of the national capital as an embarrassment. Over time his attitude changed from one of contempt to that of championing its development. He fired two ministers charged with the development of the city, feeling that their performance lacked intensity.[42]

In 1958, the newly created National Capital Development Commission (NCDC), which had been created and given more power by Menzies following a 1955 Senate inquiry,[35] restored the West Lake to its plans,[43] and it was formally gazetted in October 1959.[40] The NCDC also blocked a plan by the Department of Works to build a bridge across the lake along the land axis between Parliament House and the War Memorial contrary to Griffin's plans.[44]

A powerful Senate Select Committee oversaw the NCDC and renowned British architect Sir William Holford was brought in to fine-tune Griffin's original plans.[45] He changed the central basin's geometry so that it was no longer a segment of circle; he converted the southern straight edge into a polygonal shape with three edges and inserted a gulf on the northern shore.[46] The result was closer to Scrivener's modified design some decades earlier.[47]

Final layout

The lake contains 33,000,000 cubic metres (27,000 acre⋅ft) of water with a surface area of 6.64 square kilometres (2.56 sq mi). It is 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) long, 1.2 kilometres (0.75 mi) wide at its widest point, has a shoreline of 40.5 kilometres (25.2 mi)[48][49] and a water level of 555.93 metres (1,823.9 ft) above sea level.[50]

The lake is relatively shallow; the maximum depth is 17.6 metres (58 ft) near the Scrivener Dam, and the average depth is 4.0 metres (13 ft). The shallowest part of the complex in the East Basin, which has an average depth of 1.9 metres (6.2 ft). The minimum depth of the water at the walls is around 0.5 metres (1.6 ft) and rock is placed at the toe of the wall to inhibit aquatic plant growth.[4][50]

Lake Burley Griffin initially contained six islands, three unnamed small islands and three larger named islands.[51] Of the larger islands, Queen Elizabeth II Island is located in Central Basin while Springbank and Spinnaker Island are located in the West Lake.[51] Queen Elizabeth II Island is connected to dry land by a footbridge,[52] and is the site of the Australian National Carillon.[53] A seventh island was created as part of the Kingston Foreshore development in the East Basin, where a wide channel was excavated creating an island out of the northern most part of the Kingston Foreshore.

Construction

In 1958, engineers conducted studies into the hydrology and structural requirements needed for the building of the dam.[29] Further studies were done to model water quality, siltation, climate effects and change in land quality.[54] Modelling based on the data collection suggested that the water level could be kept within a metre of the intended level of 556 metres (1,824 ft) above sea level in the case of a flood.[55][56]

In February 1959, formal authority for beginning construction was granted.[47] However, while Menzies was on holiday, some officials from the Department of Treasury convinced ministers to withhold money needed for the lake, so the start of the construction was delayed.[47] Once it started, progress was fast.[47] At its peak, the number of people physically working on the construction in the lakes was between 400 and 500.[55] John Overall, the Commissioner of the NCDC, promised Menzies that the work would be finished within four years, and he succeeded, despite the Prime Minister's scepticism. Equipment was quickly requisitioned.[57]

After the lengthy political wrangling over the design had passed, the criticism of the scheme died down. Menzies strongly denounced the "moaning" by opponents of the lake.[57] Most critics decried the project as a waste of money that should have been spent on essential services across Australia.[57] Less strident concerns centred on the potentially negative effects of the lake, such as mosquitoes, ecological degeneration,[57] siltation and the possibility that the lake would create fog.[56] The latter of these concerns has proven to be unfounded.[58]

Lakes, islands and foreshore

The excavation of Lake Burley Griffin began in 1960 with the clearing of vegetation from the floodplain of the Molonglo River. The trees on the golf course and along the river were pulled up, along with the various sports grounds and houses.[59]

During major earthworks, at least 382,000 cubic metres (500,000 cu yd) of topsoil was excavated.[60] It was collected for use at several public parks and gardens,[60] including the future Commonwealth Park on the northern shore. It was also used to create the six artificial islands including Springbank Island. The island was named after the former Springbank Farm that was situated there.[60] Land excavated to create a sailing course at Yarralumla was used for the thematically named Spinnaker Island to its north, while excavated stone was moved beside the Kings Avenue Bridge at the eastern edge of the central basin from Queen Elizabeth II Island.[52][60][61]

Care was taken to excavate the entire lake floor to a depth of at least 2 metres (6.6 ft) to provide sufficient clearance for boat keels. Another reason given for this was that mosquitoes would not breed nor would weeds grow at such a depth.[60] A soil conservation program was launched in the catchment and bed load traps were installed to minimise loss of earth.[56] The traps have been used as a source of sand and gravel for building sites.[62] Drainage blankets were used to prevent the loss of groundwater beneath the lake.[63]

During the following phase of work, four types of lake margin were constructed.[64] On the southern side of the Central Basin, low reinforced concrete retaining walls were used,[51][64] while on the eastern side, grouted rock wall can be seen near Commonwealth Park, as well as much of the East Basin.[51][64] Sand and gravel beaches were built to cater for lakeside recreational pursuits. These are mostly prevalent on the western half of the lake complex.[51][64] Rocky outcrops, steeply sloping stable shores with water vegetation such as bullrushes were also used. This treatment is evident in the West Lake in Yarralumla.[51][64] William Holford and Partners were responsible for the foreshore landscaping, and over 55,000 trees were planted in accordance with a detailed scheme.[4][63] Eucalypts were preferred so as to maintain the natural colour of the city landscape.[63]

Bridges

Lake Burley Griffin is crossed by Commonwealth Avenue Bridge (310 metres or 1,020 feet),[60] Kings Avenue Bridge[60] (270 metres or 890 feet[65]) and a roadway over Scrivener Dam. The two bridges were constructed before the lake was filled, and replaced wooden structures.[60]

Site testing for both the Commonwealth Avenue and Kings Avenue bridges took place during late 1959 to early 1960.[55] The construction of the Kings Avenue Bridge began in 1960, followed by Commonwealth Avenue Bridge the year after.[60] Fortunately for the builders, Canberra was in a drought and the ground remained dry during construction.[55] Both bridges use post-tensioned concrete,[63] reinforced with rustproof steel cables.[66]

Both bridges are made of concrete and steel and are dual-carriageway;[67][68] Commonwealth Avenue has three lanes in each direction while Kings Avenue has two.[68][69] Instead of traditional lamp post lighting, Kings Avenue Bridge was illuminated by a series of fluorescent tubes on the handrails, a concept known as "integral lighting".[70] The design was deemed a success, so it was introduced to the Commonwealth Avenue Bridge also. Both structures won awards from the Illuminating Engineering Society.[71]

Kings Avenue Bridge opened on 10 March 1962. Prime Minister Menzies unlocked a ceremonial chain before the motorcade and pageant crossed the lake in front of a large crowd.[60] Commonwealth Avenue Bridge opened in 1963 without an official ceremony. Menzies called it "the finest building in the national capital".[60]

Dam

The dam that holds back the waters of Lake Burley Griffin was named Scrivener Dam after Charles Robert Scrivener.[47] The dam was designed and built by Rheinstahl Union Bruckenbau in West Germany,[60][64] and utilised state-of-the-art post-tensioning techniques to cope with any problems or movements in the riverbed.[55] This was required because of the quartz porphyry and geological faulting upon which the dam sits.[64] About 55,000 cubic metres (72,000 cu yd) of concrete was used in its construction. The dam is 33 metres (108 ft) high and 319 metres (1,047 ft) long with a maximum wall thickness of 19.7 metres (65 ft). The dam is designed to handle a once in 5,000-year flood event.[65] Construction began in September 1960 and the dam was locked in September 1963.[64]

The dam has five bay spillway controlled by 30.5 metres (100 ft) wide,[65] hydraulically operated fish-belly flap gates.[55] The fish-belly gates allow for a precise control of water level, reducing the dead area on the banks between high and low water levels. The five gates have only been opened simultaneously once in the dam's history, during heavy flooding in 1976.[65] The gates hold two-thirds of the lake's volume.[63] They were designed to allow easy flow of debris out of the lake.[64]

The dam has the capacity to allow a flow of 5,600 cubic metres per second (200,000 cu ft/s) but can withstand up to 8,600 cubic metres per second (300,000 cu ft/s) before "catastrophic damage" results;[62][64] A flow of 2,830 m3/s (100,000 cu ft/s) can be dealt with without any substantial change in the water level.[62] The highest recorded flow in the Molonglo was 3,400 cubic metres per second (120,000 cu ft/s) during an earlier flood.[62]

Lady Denman Drive, a roadway atop the dam wall, provides a third road crossing for the lake. It consists of a roadway and a bicycle path,[51] and allows residents in western Canberra to cross the lake.[64] This was possible because the dam gates are closed by pushing up from below, unlike most previous designs that wherein the gates were lifted from above.[72]

Lake filling

A prolonged drought coincided with and eased work on the lake's construction. The valves on the Scrivener Dam were closed on 20 September 1963 by Minister for the Interior, Gordon Freeth; Menzies was absent due to ill health.[72] Several months on, with no rain in sight, mosquito-infested pools of water were the only visible sign of the lake filling.[72] With the eventual breaking of the drought, the lake reached the planned level on 29 April 1964.[49] On 17 October 1964, Menzies (by now Sir Robert) commemorated the filling of the lake and the completion of stage one with an opening ceremony amid the backdrop of sailing craft.[49][73] The ceremony was accompanied by fireworks display, and Griffin's lake had finally come to fruition after five decades, at the cost of A$5,039,050 (equivalent to $70,900,000 in 2018).[49][63] Freeth suggested that Menzies had "been in a material sense the father of the lake" and that the lake should be named after him.[74] Menzies insisted that the lake should be named after Griffin.[47]

In times of severe drought, Lake Burley Griffin's water level can fall unacceptably low. When this happens, a release of water from Googong Dam located upstream can be scheduled to top up and restore the lake water level.[75] The Googong Dam is on the Queanbeyan River which is a tributary of the Molonglo River.[76] The dam whose construction was finished in 1979 is one of three dams—the Cotter and Corin Dams are the others—that meet the water supply needs of the Canberra and Queanbeyan region.[77] The Googong Dam's water carrying capacity is 124,500,000 cubic metres (100,900 acre⋅ft).[76]

Later history and development

Griffin's design made the lake a focal point of the city. In the four decades since the initial construction of the lake, various buildings of national importance were added. According to the policy plan of the government, "The lake is not only one of the centrepieces of Canberra's plan in its own right, but forms the immediate foreground of the National Parliamentary Area."[48]

The creation of the lake also gave a water frontage to many prominent institutions that were previously landlocked. The Royal Canberra Hospital was located on the Acton Peninsula between the West Lake and the West Basin on the north shore until its demolition.[78] Government House, the historic Blundell's Cottage—which was built over 50 years before construction of Canberra began—and the newly built Australian National University, on the southern and northern shores of the West Lake, both gained a waterfront.[78]

In 1970, two tourist attractions were added to the middle of Central Basin. The Captain James Cook Memorial was built by the government to commemorate the Bicentenary of (then Lieutenant) James Cook's first sighting of the east coast of Australia. It includes a water jet fountain located in the central basin (based on the Jet d'eau[79] in Geneva) and a skeleton globe sculpture at Regatta Point showing the paths of Cook's expeditions. On 25 April 1970, Queen Elizabeth II officially inaugurated the memorial.[80] As part of the same ceremony, Queen Elizabeth also opened the National Carillon on Queen Elizabeth II Island, a set of 53 bronze bells donated by the British Government to commemorate the city's 50th anniversary.[53]

The completion of the central basin placed a waterway between Parliament House and the War Memorial and a landscaped boulevard was built along the land axis.[81] Later, various buildings of national importance were built along the land axis in the late-1960s through to the early 1980s. The National Library was opened on the western side of the axis in April 1968.[82] Building of the High Court and National Gallery occurred in the late-1970s and the buildings were opened in May 1980 and October 1982 respectively.[83] The latter two buildings lie on the eastern side of the axis and are connected by an aerial bridge.[52][84] In 1988, the new Parliament House was built on Capital Hill, thereby completing the most important structure in the Parliamentary Triangle.[52]

The current home of the National Museum was built on the former site of the Royal Canberra Hospital in 2001.[14][52] This occurred after the public were encouraged to watch the controlled demolition of the hospital in 1997, but a girl was killed by flying debris, leading to criticism of the ACT Government.[85]

At the start of the 21st century, the layout of the lake was significantly altered for the first time since its construction, through the Kingston Foreshores Redevelopment on southern shore of the East Basin, which was planned in 1997.[86] A bidding process was enacted,[87] multimillion-dollar luxury apartment complexes were built in the suburb of Kingston,[88] driving property values to record-breaking levels.[86] After a dispute over the environmental impact of the development, building works commenced on the previously industrial lakeside area of the suburb.[89][90] In 2007, work started to reclaim land from the lakebed to form a harbour.[86]

The Kingston Powerhouse, which used to provide the city's power supply, was converted into the Canberra Glassworks in 2007, 50 years after the electricity generators stopped.[91] A 25-metre-high (82 ft) tower of glass and light named Touching Lightly was unveiled on 21 May 2010 by Chief Minister and Minister for the Arts and Heritage Jon Stanhope. It was built by Australian artist Warren Langley.[92]

In 2007, the government unveiled a proposal to redevelop the area surrounding the historic Albert Hall into a tourist and dining precinct. This included the building of an eight-storey building and the rezoning of some waterfront land currently designated as cultural to commercial.[93] It was met with widespread hostility from heritage activists and the general community, which submitted more than 3,300 signatories in a petition against the scheme.[94][95] One of the criticisms was that the project was tilted too heavily towards business, and neglected the arts and community events.[96] The proposal was scrapped in 2009.[97][98][99]

It was proposed that a footbridge, to be named Immigration Bridge, be built between the National Museum of Australia and Lennox Gardens on the south shore, in recognition of the contributions that immigrants have made to Australia.[100] The proposal mostly received negative feedback.[101] An inquiry recommended that the bridge be redesigned or moved to accommodate the needs of other lake users.[102] The proposal was abandoned in March 2010.[103]

Lakeside recreation

The surrounds of Lake Burley Griffin are very popular recreational areas, and is known locally as LBG. Public parks exist along most of the shore line, with free electric barbecue facilities, fenced-in swimming areas, picnic tables and toilets.[52] These parklands form a large part of the area around the lake, and occupy 3.139 km2 (776 acres) in total.[50] Some of the parks reserved for public recreation include Commonwealth, Weston, Kings and Grevillea Parks, Lennox Gardens and Commonwealth Place.[52] Commonwealth and Kings Park on the northern shore of the Central Basin are among the two most popular. The former is an urban horticultural park and is the location of the Canberra Festival.[14]

Commonwealth Park is the location of Floriade, an annual flower festival that is held for around a month in spring and attracts upwards of 300,000 visitors,[104] a number comparable to the city population. The largest flower festival in Australia,[105] the event is a major tourist attraction for the city, and legal action was threatened after another festival in Australia wanted to use the same name.[106] An expansion is being planned to coincide with the centenary of the national capital.[107] The Weston Park to the west is known for its woodland and conifers, while Black Mountain Peninsula is known as a picnicking site with eucalypts.[14] Grevillea and Bowen Parks on the East Basin tend to be little used.[78]

Owing to the proliferation of beaches, boat ramps and jetties, the West Lake is the area most used by swimmers and vessels.[14] A bike path also surrounds the lake, and riding, walking or jogging around the lake are a popular activity on the weekends.[2][78][108] Fireworks are often held over the lake on New Year's Eve, and a large show called Skyfire has been held at the lake since 1989.[109][110]

Water sports

Lake Burley Griffin, apart from being ornamental, is used for many recreational activities. Canoeing, sailing, paddleboating, windsurfing and dragon boating are popular.[78] A rowing course is set up at the western end of the lake.[111] The National Championships were held in the lake in 1964,[61] but high winds have deterred organisers. On one occasion, winds swept a boat into a bridge pylon.[112] While not particularly popular, opportunities for swimming have been limited recently because of increasingly frequent lake closures due to concerns about water quality;[113] another deterrent against swimming is the generally cold water temperature.[111][114] During summer, the lake is used for the swim leg of numerous triathlon and aquathlon events including the Sri Chinmoy Triathlon Festival.[115]

Generally, powerboat use on the lake is not permitted. Permits are available for the use of powered boats on the lake for use in rescue, training, commercial purposes or special interest (such as historic steam-powered boats).[116] Molonglo Reach, an area of the Molonglo River just before it enters the east basin is set aside for water skiing. Ten powerboats may be used in this limited area.[117]

Safety

The lake is patrolled by the Australian Federal Police water police.[49] The water police give assistance to lake users, helping to right boats and towing crippled craft to shore.[49]

At most swimming locations around Lake Burley Griffin there are fenced-in swimming areas for safety. In the more popular areas, there are also safety lockers with life belts and emergency phones for requesting help. Between 1962 and 1991, seven people died from drowning.[118]

For safety and water quality reasons, the lake has different zones for different activities.[119] The eastern extremity is zoned for primary contact water activities such as swimming and water skiing.[119] The East and Central Basins, closer to populated areas, are zoned for secondary contact water sports such as sailing or rowing.[119] West Lake and Tarcoola Reach, which covers the area between Commonwealth Avenue and Kurrajong Point, is the primary recreational area of the lake, and both primary and secondary contact water sports are permitted.[119] Yarramundi Reach near Scrivener Dam has a marked rowing course, and is zoned as secondary, although primary contact activities are also allowed.[119]

Environmental issues

Water quality

Toxic blue-green algae blooms are a reasonably common occurrence in the lake.[120] Warnings about coming into contact with the water are released when an algal bloom is detected. Attempts are being made to limit the amount of phosphates entering the lake in the hope of improving its water quality.[121] Blue-green algae (more correctly cyanobacteria) produce toxins, which can be harmful for humans and any other animals that come in contact with the contaminated water. There have been several cases of dogs being affected after playing in and drinking the lake water.[122]

The water also appears murky due to a high level of turbidity;[114] however, this is not usually a health risk.[114] However, the turbidity, which is caused by wind, prevents photosynthetic stabilisation.[123] Siltation is not considered a major problem and is only a factor in the East Basin, but dredging is not required. The problem has eased with the construction of the Googong Dam, and the spectre of heavy metal pollution has receded,[120] partly due to the closure of some lead mines upstream.[58] However, leaching and groundwater leakage still causes some pollution.[58] Rubbish, oil and sediment traps have been set up at the incoming openings to the lake to minimise pollution.[120]

Aquatic life and fishing

Fishing is quite popular in the lake. The most common species caught is the illegally introduced carp.[120] Annual monitoring is carried out to determine fish populations. Almost equally as common are the introduced redfin European perch, with these being a regular by catch when fishing for golden perch. However, a number of less common species also inhabit the lake, including native Murray cod, western carp gudgeon and golden perch, as well as introduced goldfish, Gambusia, rainbow trout and brown trout.[124]

The lake has been stocked annually with a variety of introduced and native species and over half a million fish have been released since 1981.[125] There have been many changes to the fish populations in the lake as well as stocking practices since it was first filled.[125]

Regular stocking since the start of the 1980s have re-established reasonable populations of golden perch and Murray cod;[125] native fish that were indigenous to the Molonglo River before the lake was built, but had been lost to mining pollution of the Molonglo River in the first half of the 20th century.[126] The main reason for stocking is to boost fish stocks along the Molonglo, which have been depleted by overfishing, introduced species and habitat destruction. One of the motives for raising the level of Murray cod and golden perch is to balance the ecosystem by having them act as native predators of other fish.[126]

Native Silver perch and introduced brown trout were released in 1981–1983 and 1987–1989 respectively, but have not been stocked since.[125] Silver perch stockings resulted in almost no captures. Introduced rainbow trout have been released sporadically, approximately once a decade, but have not been released since 2002–04,[125] due to unacceptably low survival rates. According to a government report, the reason for the low survival rate is unknown, but the dominance of carp in the competition for food is one suggested theory.[125] However, the eutrophic nature and high water temperatures of the lake in summer are more probable reasons. Golden perch and Murray cod have accounted for around four-fifths of the released fish in the last three decades and have been the only fish stocked in the last five years.[125] The government plans to stock only these two species for the five years leading up to 2014.[127]

Engineering heritage award

The lake is listed as a National Engineering Landmark by Engineers Australia as part of its Engineering Heritage Recognition Program.[128]

Notes

- Maher, Norris et al (1992). Zinc in the sediments, water and biota of Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra, in The Science of the Total Environment, ISSN 0048-9697, p. 238.

- "Lake Burley Griffin and Surrounding Parklands". National Capital Authority. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra : Policy Plan, p. 3.

- Andrews, p. 88.

- Sparke, pp. 4–7.

- "Canberra contour survey". National Library of Australia. 1909. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- The Griffin Legacy. Canberra: National Capital Authority. 2004. p. 51. ISBN 0-9579550-2-2.

- Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra : Policy Plan, p. 4.

- Wigmore, p. 67.

- Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra : Policy Plan, pp. 6–7.

- Andrews, p. 89.

- Wigmore, p. 64.

- Sparke, pp. 1–3.

- Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra : Policy Plan, p. 17.

- "Short history". Canberra House. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

- Hoyle, Arthur (1988). "O'Malley, King (1858–1953)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- Wigmore, pp. 52–57.

- Andrews, pp. 88–89.

- Wigmore, pp. 61–63.

- Wigmore, p. 63.

- Wigmore, pp. 69–79.

- Sparke, p. 2.

- Sparke, p. 6.

- Sparke, pp. 7–9.

- Minty, p. 804.

- Sparke, p. 14.

- Sparke, pp. 6–7.

- Sparke, p. 5.

- Sparke, p. 131.

- Wigmore, p. 151.

- Wigmore, p. 152.

- Sparke, p. 13.

- Sparke, p. 11.

- Sparke, pp. 13–14.

- Andrews, p. 90.

- Sparke, pp. 13–15.

- Sparke, p. 16.

- Sparke, pp. 16–17.

- Sparke, pp. 15–16.

- Sparke, p. 17.

- Sparke, p. 30.

- Sparke, pp. 31–32.

- Wigmore, p. 153.

- Sparke, pp. 19–21.

- Sparke, pp. 56–57.

- Sparke, pp. 60–61.

- Sparke, p. 132.

- Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra : Policy Plan, p. 1.

- Sparke, p. 141.

- Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra : Policy Plan, p. 8.

- Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra : Policy Plan, p. 9.

- "Lake Burley Griffin Interactive Map". National Capital Authority. Archived from the original on 22 May 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- Sparke, p. 174.

- Andrews, p. 91.

- Sparke, p. 136.

- Andrews, p. 92.

- Sparke, p. 135.

- Minty, p. 808.

- Sparke, pp. 136–138.

- Sparke, p. 138.

- Andrews, p. 94.

- Minty, p. 806.

- Minty, p. 809.

- Andrews, p. 93.

- Scrivener Dam (PDF). National Capital Authority. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- Andrews, p. 34.

- Sparke, pp. 138–139.

- Wigmore, p. 189.

- Andrews, pp. 30–31.

- Andrews, p. 141.

- Andrews, pp. 141–142.

- Sparke, p. 140.

- "Menzies Virtual Museum – 1964". Sir Robert Menzies Memorial Foundation. Archived from the original on 19 January 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- Sparke, pp. 97, 132.

- Sparke, pp. 220–221.

- ACT Infrastructure Five-yearly report to the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), p. 42.

- ACT Infrastructure Five-yearly report to the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), pp. 40–41.

- Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra : Policy Plan, p. 18.

- "Captain Cook Memorial" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- Sparke, pp. 173–174.

- Sparke, pp. 113–116.

- Sparke, pp. 170–171.

- Sparke, pp. 307–310.

- Sparke, p. 311.

- "Increasing pressure on ACT Chief Minister". A.M. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 5 November 1999. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- "ACT Govt awards Kingston harbour contract". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 7 April 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- "Six companies short-listed for Kingston Foreshore Project". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 23 June 2003. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- "Developer buys first Kingston Foreshore land". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 September 2003. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- "Landscaping, waste water concerns hit Kingston development". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 31 March 2005. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- "Kingston Foreshore". Macmahon. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- "Canberra Glassworks celebrates first birthday". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 23 May 2008. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- Touching Lightly ACT Government Public Art at Canberra Glassworks, Canberra glass works, archived from the original on 10 September 2015, retrieved 4 August 2015

- "National Capital Plan Draft Amendment 53 – Albert Hall Precinct" (PDF). National Capital Authority. February 2007. pp. 11, 19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "Petitioners seek to stop hall development". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 14 May 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "Historian hits out at Albert Hall development plans". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 26 March 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "Experts want Albert Hall to be used for community activities". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 3 April 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "Facelift planned for Albert Hall precinct". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 22 February 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "Albert Hall development plans axed". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 22 June 2009. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "No news is bad news for Albert Hall: lobby group". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 7 October 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- Doherty, Megan (31 March 2009). "Clamour to scuttle bridge proposal". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "Canberrans speak out on proposed memorial bridge". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 28 March 2009. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "Lake users must agree to footbridge: committee". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 29 May 2009. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "Immigration Bridge plans collapse". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 30 March 2010.

- "Organisers tip record Floriade crowd". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 10 October 2006. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- "Floriade herbs". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 20 September 2004. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- "Legal row brews over NSW Floriade event". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 September 2005. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- "Floriade to expand to 3 locations, says Govt". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 30 April 2009. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra : Policy Plan, p. 25.

- "Skyfire 09". Australian Federal Police. 17 March 2009. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- "Upcoming Events". National Capital Authority. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra : Policy Plan, p. 13.

- Sparke, pp. 138–144.

- "Lake remains closed to swimmers". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 September 2003. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra : Policy Plan, p. 27.

- "Sri Chinmoy Triathlon". National Capital Authority. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- "Boating on Lake Burley Griffin". National Capital Authority. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- "Water Skiing". Canberra Connect. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- "Casuarina Sands Weir" (PDF). Hansard. Australian Capital Territory Legislative Assembly. 21 February 1991. p. 614. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Lake Burley Griffin Water Quality Management Plan". National Capital Authority. June 2004. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra : Policy Plan, p. 28.

- "Territory and Municipal Services – Blue-Green Algae Monitoring". ACT Environment Protection Authority. 29 May 2009. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- "Algae closes all lakes Blue-green menace here to stay: learn to live with it, says expert". Newsletter. Australian Institute of Marine Science. October 2003. Archived from the original on 28 April 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- Minty, p. 810.

- "Fishing information & lake map of Lake Burley Griffin". Sweetwater Fishing. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- Draft for public comment: Fish stocking plan for the Australian Capital Territory 2009–2014, pp. 5–6.

- Draft for public comment: Fish stocking plan for the Australian Capital Territory 2009–2014, p. 4.

- Draft for public comment: Fish stocking plan for the Australian Capital Territory 2009–2014, p. 14.

- "Lake Burley Griffin Scheme, Molonglo River, 1964-". Engineers Australia. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

References

- ACT Infrastructure Five-yearly report to the Council of Australian Governments (COAG). ACT Chief Minister’s Department. January 2007.

- Draft for public comment: Fish stocking plan for the Australian Capital Territory 2009–2014. Department of Territory and Municipal Services. January 2009.

- Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra : Policy Plan. National Capital Development Commission. 1988. ISBN 0-642-13957-1.

- Andrews, W. C., ed. (1990). Canberra's Engineering Heritage. Institution of Engineers Australia. ISBN 0-85825-496-4.

- Minty, A. E. (1973). Man-Made Lakes: Their Problems and Environmental Effects. William Byrd Press. ISBN 0-87590-017-8.

- Sparke, Eric (1988). Canberra 1954–1980. Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-08060-4.

- Wigmore, Lionel (1971). Canberra: history of Australia's national capital. Dalton Publishing Company. ISBN 0-909906-06-8.

External links

- Lake Burley Griffin Heritage Assessment with "Lake Burley Griffin and Adjacent Lands Draft Heritage Management Plan"