Mono Lake

Mono Lake (/ˈmoʊnoʊ/ MOH-noh) is a saline soda lake in Mono County, California, formed at least 760,000 years ago as a terminal lake in an endorheic basin. The lack of an outlet causes high levels of salts to accumulate in the lake which make its water alkaline.[2]

| Mono Lake | |

|---|---|

Aerial photograph of Mono Lake | |

Mono Lake Location of Mono Lake in California | |

| Location | Mono County, California |

| Coordinates | 38°01′00″N 119°00′34″W |

| Type | Endorheic, Monomictic |

| Primary inflows | Rush Creek, Lee Vining Creek, Mill Creek |

| Primary outflows | Evaporation |

| Catchment area | 780 sq mi (2,030 km2) |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Max. length | 13 mi (21 km) |

| Max. width | 9.3 mi (15 km) |

| Surface area | 45,133 acres (18,265 ha)[1] |

| Average depth | 57 ft (17 m)[1] |

| Max. depth | 159 ft (48 m)[1] |

| Water volume | 2,970,000 acre⋅ft (3.66 km3) |

| Surface elevation | 6,383 ft (1,946 m) above sea level |

| Islands | Two major: Negit Island and Paoha Island; numerous minor outcroppings (including tufa rock formations). The lake's water level is notably variable. |

| References | U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Mono Lake |

The desert lake has an unusually productive ecosystem based on brine shrimp, which thrive in its waters, and provides critical habitat for two million annual migratory birds that feed on the shrimp and alkali flies (Ephydra hians).[3][4] Historically, the native Kutzadika'a people ate the alkali flies' pupae, which live in the shallow waters around the edge of the lake.[5]

When the city of Los Angeles diverted water from the freshwater streams flowing into the lake, it lowered the lake level, which imperiled the migratory birds. The Mono Lake Committee formed in response and won a legal battle that forced Los Angeles to partially replenish the lake level.[6]

Geology

Mono Lake occupies part of the Mono Basin, an endorheic basin that has no outlet to the ocean. Dissolved salts in the runoff thus remain in the lake and raise the water's pH levels and salt concentration. The tributaries of Mono Lake include Lee Vining Creek, Rush Creek and Mill Creek which flows through Lundy Canyon.[7]

The basin was formed by geological forces over the last five million years: basin and range crustal stretching and associated volcanism and faulting at the base of the Sierra Nevada.[8]: 45

From 4.5 to 2.6 million years ago, large volumes of basalt were extruded around what is now Cowtrack Mountain (east and south of Mono Basin); eventually covering 300 square miles (780 km2) and reaching a maximum thickness of 600 feet (180 m).[8]: 45 Later volcanism in the area occurred 3.8 million to 250,000 years ago.[8]: 46 This activity was northwest of Mono Basin and included the formation of Aurora Crater, Beauty Peak, Cedar Hill (later an island in the highest stands of Mono Lake), and Mount Hicks.

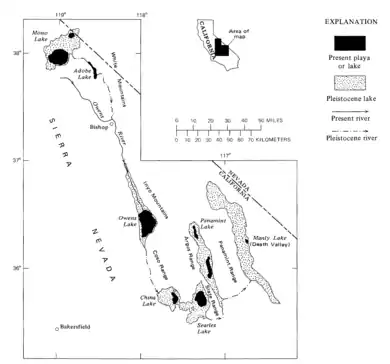

Lake Russell was the prehistoric predecessor to Mono Lake, during the Pleistocene. Its shoreline reached the modern-day elevation of 7,480 feet (2,280 m), about 1,100 feet (330 m) higher than the present-day lake. As of 1.6 million years ago, Lake Russell discharged to the northeast, into the Walker River drainage. After the Long Valley Caldera eruption 760,000 years ago, Lake Russell discharged into Adobe Lake to the southeast, then into the Owens River, and eventually into Lake Manly in Death Valley.[9] Prominent shore lines of Lake Russell, called strandlines by geologists, can be seen west of Mono Lake.[10]

The area around Mono Lake is currently geologically active. Volcanic activity is related to the Mono-Inyo Craters: the most recent eruption occurred 350 years ago, resulting in the formation of Paoha Island.[11] Panum Crater (on the south shore of the lake) is an example of a combined rhyolite dome and cinder cone.[12]

Tufa towers

Many columns of limestone rise above the surface of Mono Lake. These limestone towers consist primarily of calcium carbonate minerals such as calcite (CaCO3). This type of limestone rock is referred to as tufa, which is a term used for limestone that forms in low to moderate temperatures.[13]

Tufa tower formation

Mono Lake is a highly alkaline lake, or soda lake. Alkalinity is a measure of how many bases are in a solution, and how well the solution can neutralize acids. Carbonate (CO32-) and bicarbonate (HCO3−) are both bases. Hence, Mono Lake has a very high content of dissolved inorganic carbon. Through supply of calcium ions (Ca2+), the water will precipitate carbonate-minerals such as calcite (CaCO3). Subsurface waters enter the bottom of Mono Lake through small springs. High concentrations of dissolved calcium ions in these subsurface waters cause huge amounts of calcite to precipitate around the spring orifices.[14]

The tufa originally formed at the bottom of the lake. It took many decades or even centuries to form the well-recognized tufa towers. When lake levels fell, the tufa towers came to rise above the water surface and stand as the pillars seen today (see Lake Level History for more information).[15]

Tufa morphology

Description of the Mono Lake tufa dates back to the 1880s, when Edward S. Dana and Israel C. Russell made the first systematic descriptions of the Mono Lake tufa.[17][16] The tufa occurs as "modern" tufa towers. There are tufa sections from old shorelines, when the lake levels were higher. These pioneering works in tufa morphology are referred to by researchers and were confirmed by James R. Dunn in 1953. The tufa types can roughly be divided into three main categories based on morphology:[14][18]

- Lithoid tufa - massive and porous with a rock-like appearance

- Dendritic tufa - branching structures that look similar to small shrubs

- Thinolitic tufa - large well-formed crystals of several centimeters

Through time, many hypotheses were developed regarding the formation of the large thinolite crystals (also referred to as glendonite) in thinolitic tufa. It was relatively clear that the thinolites represented a calcite pseudomorph after some unknown original crystal.[16] The original crystal was only determined when the mineral ikaite was discovered in 1963.[19] Ikaite, or hexahydrated CaCO3, is metastable and only crystallizes at near-freezing temperatures. It is also believed that calcite crystallization inhibitors such as phosphate, magnesium, and organic carbon may aid in the stabilization of ikaite.[20] When heated, ikaite breaks down and becomes replaced by smaller crystals of calcite.[21][22] In the Ikka Fjord of Greenland, ikaite was also observed to grow in columns similar to the tufa towers of Mono Lake.[23] This has led scientists to believe that thinolitic tufa is an indicator of past climates in Mono Lake because they reflect very cold temperatures.[24]

Tufa chemistry

Russell (1883) studied the chemical composition of the different tufa types in Lake Lahontan, a large Pleistocene system of multiple lakes in California, Nevada, and Oregon. Not surprisingly, it was found that the tufas consisted primarily of CaO and CO2. However, they also contain minor constituents of MgO (~2 wt%), Fe/Al-oxides (.25-1.29 wt%), and PO5 (0.3 wt%).

Climate

| Climate data for Mono Lake, CA | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 66 (19) |

68 (20) |

72 (22) |

80 (27) |

87 (31) |

96 (36) |

97 (36) |

95 (35) |

91 (33) |

85 (29) |

74 (23) |

65 (18) |

97 (36) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 40.4 (4.7) |

44.5 (6.9) |

50.5 (10.3) |

58.4 (14.7) |

67.6 (19.8) |

76.6 (24.8) |

83.8 (28.8) |

82.7 (28.2) |

75.9 (24.4) |

65.5 (18.6) |

51.7 (10.9) |

42.2 (5.7) |

61.7 (16.5) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 19.7 (−6.8) |

21.5 (−5.8) |

24.8 (−4.0) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

36.4 (2.4) |

43.2 (6.2) |

49.6 (9.8) |

49.0 (9.4) |

42.8 (6.0) |

34.6 (1.4) |

27.3 (−2.6) |

21.8 (−5.7) |

33.4 (0.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −6 (−21) |

−4 (−20) |

1 (−17) |

12 (−11) |

16 (−9) |

25 (−4) |

35 (2) |

32 (0) |

18 (−8) |

8 (−13) |

7 (−14) |

−4 (−20) |

−6 (−21) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.17 (55) |

2.21 (56) |

1.38 (35) |

0.66 (17) |

0.57 (14) |

0.36 (9.1) |

0.55 (14) |

0.45 (11) |

0.63 (16) |

0.64 (16) |

1.96 (50) |

2.32 (59) |

13.9 (352.1) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 15.5 (39) |

15.3 (39) |

11.4 (29) |

3.1 (7.9) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.7 (1.8) |

7.6 (19) |

12.0 (30) |

66 (166.7) |

| Source: http://www.wrcc.dri.edu/cgi-bin/cliMAIN.pl?ca5779 | |||||||||||||

Limnology

The limnology of the lake shows it contains approximately 280 million tons of dissolved salts, with the salinity varying depending upon the amount of water in the lake at any given time. Before 1941, average salinity was approximately 50 grams per liter (g/L) (compared to a value of 31.5 g/L for the world's oceans). In January 1982, when the lake reached its lowest level of 1,942 metres (6,372 ft), the salinity had nearly doubled to 99 g/L. In 2002, it was measured at 78 g/L and is expected to stabilize at an average 69 g/L as the lake replenishes over the next 20 years.[25]

An unintended consequence of ending the water diversions was the onset of a period of "meromixis" in Mono Lake.[26] In the time prior to this, Mono Lake was typically "monomictic"; which means that at least once each year the deeper waters and the shallower waters of the lake mixed thoroughly, thus bringing oxygen and other nutrients to the deep waters. In meromictic lakes, the deeper waters do not undergo this mixing; the deeper layers are more saline than the water near the surface, and are typically nearly devoid of oxygen. As a result, becoming meromictic greatly changes a lake's ecology.[27]

Mono Lake has experienced meromictic periods in the past; this most recent episode of meromixis, brought on by the end of the water diversions, commenced in 1994 and had ended by 2004.[28]

Lake-level history

An important characteristic of Mono Lake is that it is a closed lake, meaning it has no outflow. Water can only escape the lake if it evaporates or is lost to groundwater. This may cause closed lakes to become very saline. The reconstruction of historical Mono Lake levels through carbon and oxygen isotopes have also revealed a correlation with well-documented changes in climate.[29]

In the recent past, Earth experienced periods of increased glaciation known as ice ages. This geological period of ice ages is known as the Pleistocene, which lasted until ~11 ka. Lake levels in Mono Lake can reveal how the climate fluctuated. For example, during the cold climate of the Pleistocene the lake level was higher because there was less evaporation and more precipitation. Following the Pleistocene, the lake level was generally lower due to increased evaporation and decreased precipitation associated with a warmer climate.[29]

The lake level has fluctuated during the Holocene, since the end of the ice ages. The Holocene high point is at elevation 6,499 feet (1,980.8 m), reached in approximately 1820 BCE.[30] The low point before modern diversions is at elevation 6,368 feet (1,940.9 m), reached in 143 CE.[30] The lowest modern level due to diversions is at 6,372.0 feet (1,942.2 m), reached in 1980.[31]

Ecology

Aquatic life

The hypersalinity and high alkalinity (pH=10 or equivalent to 4 milligrams of NaOH per liter of water) of the lake means that no fish are native to the lake.[32] An attempt by the California Department of Fish and Game to stock the lake failed.[33]

The whole food chain of the lake is based on the high population of single-celled planktonic algae present in the photic zone of the lake. These algae reproduce rapidly during winter and early spring after winter runoff brings nutrients to the surface layer of water. By March the lake is "as green as pea soup" with photosynthesizing algae.[34]

The lake is famous for the Mono Lake brine shrimp, Artemia monica, a tiny species of brine shrimp, no bigger than a thumbnail, that are endemic to the lake. During the warmer summer months, an estimated 4–6 trillion brine shrimp inhabit the lake. Brine shrimp have no food value for humans, but are a staple for birds of the region. The brine shrimp feed on microscopic algae.[35]

Alkali flies, Ephydra hians, live along the shores of the lake and walk underwater, encased in small air bubbles, for grazing and to lay eggs. These flies are an important source of food for migratory and nesting birds.[36]

Eight nematode species were found living in the littoral sediment:[37]

- Auanema spec., which is outstanding for its extreme arsenic resistance (survives concentrations 500 times higher than humans), having 3 sexes, and being viviparous.

- Pellioditis spec.

- Mononchoides americanus

- Diplogaster rivalis

- species of the family Mermithidae

- Prismatolaimus dolichurus

- 2 species of the order Monhysterida

Birds

_33.JPG.webp)

Mono Lake is a vital resting and eating stop for migratory shorebirds and has been recognized as a site of international importance by the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network.[38] Nearly 2,000,000 waterbirds, including 35 species of shorebirds, use Mono Lake to rest and eat for at least part of the year. Some shorebirds that depend on the resources of Mono Lake include American avocets, killdeer, and sandpipers. One to two million eared grebes and phalaropes use Mono Lake during their long migrations.[39]

Late every summer tens of thousands of Wilson's phalaropes and red-necked phalaropes arrive from their nesting grounds, and feed until they continue their migration to South America or the tropical oceans respectively.[3]

In addition to migratory birds, a few species spend several months to nest at Mono Lake. Mono Lake has the second largest nesting population of California gulls, Larus californicus, second only to the Great Salt Lake in Utah. Since abandoning the landbridged Negit Island in the late 1970s, California gulls have moved to some nearby islets and have established new, if less protected, nesting sites. Cornell University and Point Blue Conservation Science have continued the study of nesting populations on Mono Lake that was begun 35 years ago. Snowy plovers also arrive at Mono Lake each spring to nest along the northern and eastern shores.[40]

History

Native Americans

The indigenous people of Mono Lake are from a band of the Northern Paiute, called the Kutzadika'a.[41] They speak the Northern Paiute language.[42] The Kutzadika'a traditionally forage alkali fly pupae, called kutsavi in their language.

The term "Mono" is derived from "Monachi", a Yokuts term for the tribes that live on both the east and west side of the Sierra Nevada.[43]

During early contact, the first known Mono Lake Paiute chief was Captain John.[44]

The Mono tribe has two bands: Eastern and Western. The Eastern Mono joined the Western Mono bands' villages annually at Hetch Hetchy Valley, Yosemite Valley, and along the Merced River to gather acorns, different plant species, and to trade. The Western Mono and Eastern mono traditionally lived in the south-central Sierra Nevada foothills, including Historical Yosemite Valley.[45]

Present day Mono Reservations are currently located in Big Pine, Bishop, and several in Madera County and Fresno County, California.

Conservation efforts

.jpg.webp)

The city of Los Angeles diverted water from the Owens River into the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913. In 1941, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power extended the Los Angeles Aqueduct system farther northward into the Mono Basin with the completion of the Mono Craters Tunnel[46] between the Grant Lake Reservoir on Rush Creek and the Upper Owens River. So much water was diverted that evaporation soon exceeded inflow and the surface level of Mono Lake fell rapidly. By 1982 the lake was reduced to 37,688 acres (15,252 ha), 69 percent of its 1941 surface area. By 1990, the lake had dropped 45 vertical feet and had lost half its volume relative to the 1941 pre-diversion water level.[47] As a result, alkaline sands and formerly submerged tufa towers became exposed, the water salinity doubled, and Negit Island became a peninsula, exposing the nests of California gulls to predators (such as coyotes), and forcing the gull colony to abandon this site.[48]

In 1974, ecologist David Gaines and his student David Winkler studied the Mono Lake ecosystem and became instrumental in alerting the public of the effects of the lower water level with Winkler's 1976 ecological inventory of the Mono Basin.[49] The National Science Foundation funded the first comprehensive ecological study of Mono Lake, conducted by Gaines and undergraduate students. In June 1977, the Davis Institute of Ecology of the University of California published a report, "An Ecological Study of Mono Lake, California," which alerted California to the ecological dangers posed by the redirection of water away from the lake for municipal uses.[49]

Gaines formed the Mono Lake Committee in 1978. He and Sally Judy, a UC Davis student, led the committee and pursued an informational tour of California. They joined with the Audubon Society to fight a now famous court battle, the National Audubon Society v. Superior Court, to protect Mono Lake through state public trust laws.[49] While these efforts have resulted in positive change, the surface level is still below historical levels, and exposed shorelines are a source of significant alkaline dust during periods of high winds.[50]

Owens Lake, the once-navigable terminus of the Owens River which had sustained a healthy ecosystem, is now a dry lake bed during dry years due to water diversion beginning in the 1920s. Mono Lake was spared this fate when the California State Water Resources Control Board (after over a decade of litigation) issued an order (SWRCB Decision 1631) to protect Mono Lake and its tributary streams on September 28, 1994.[51] SWRCB Board Vice-chair Marc Del Piero was the sole Hearing Officer (see D-1631). In 1941 the surface level was at 6,417 feet (1,956 m) above sea level.[31] As of October 2022, Mono Lake was at 6,378.7 feet (1,944 m) above sea level.[31] The lake level of 6,392 feet (1,948 m) above sea level is the goal, designed to ensure that the lake would be able to reach and sustain a minimum surface level that is generally agreed to be the minimum for keeping the ecosystem healthy.[52] It has more difficult during years of drought in the American West.[53]

In popular culture

Artwork

In 1968, the artist Robert Smithson made Mono Lake Non-Site (Cinders near Black Point)[54] using pumice collected while visiting Mono on July 27, 1968, with his wife Nancy Holt and Michael Heizer (both prominent visual artists). In 2004, Nancy Holt made a short film entitled Mono Lake using Super 8 footage and photographs of this trip. An audio recording by Smithson and Heizer, two songs by Waylon Jennings, and Michel Legrand's Le Jeu, the main theme of Jacques Demy's film Bay of Angels (1963), were used for the soundtrack.[55]

The Diver, a photo taken by Aubrey Powell of Hipgnosis for Pink Floyd's album Wish You Were Here (1975), features what appears to be a man diving into a lake, creating no ripples. The photo was taken at Mono Lake, and the tufa towers are a prominent part of the landscape. The effect was actually created when the diver performed a handstand underwater until the ripples dissipated.[56]

In print

Mark Twain's Roughing It, published in 1872, provides an informative early description of Mono Lake in its natural condition in the 1860s.[57][58] Twain found the lake to be a "lifeless, treeless, hideous desert... the loneliest place on earth."[59][60]

In film

A scene featuring a volcano in the film Fair Wind to Java (1953) was shot at Mono Lake.[61]

Most of the film High Plains Drifter (1973) by Clint Eastwood was shot on the southern shores of Mono Lake in the 1970s. An entire town was built here for the film, and later removed when shooting was complete.[62]

In music

The music video for glam metal band Cinderella's 1988 power ballad Don't Know What You Got ('Till It's Gone) was filmed by the lake.[63]

See also

- Bodie, a nearby ghost town

- List of lakes in California

- Mono Lake Tufa State Reserve

- Mono Basin National Scenic Area

- GFAJ-1, an organism from Mono Lake that has been at the center of a scientific controversy over hypothetical arsenic in DNA.

- List of drying lakes

- Whoa Nellie Deli, located in Lee Vining, California, overlooking Mono Lake

- Monolake, a Berlin-based electronic music project named after the lake

References

- "Quick Facts About Mono Lake". Mono Lake Committee. Archived from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- "Water Chemistry". Mono Lake Committee. January 14, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- "Birds of the Basin: the Migratory Millions of Mono". Mono Lake Committee. Archived from the original on August 31, 2013. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- Carle, David (2004). Introduction to Water in California. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24086-3.

- "Mono Lake". American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- Hart, John (1996). Storm Over Mono: The Mono Lake Battle and the California Water Future. University of California Press.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Lundy Canyon

- Tierney, Timothy (2000). Geology of the Mono Basin (revised ed.). Lee Vining, California: Kutsavi Press, Mono Lake Committee. pp. 45–46. ISBN 0-939716-08-9.

- Reheis, MC; Stine, S; Sarna-Wojcicki, AM (2002). "Drainage reversals in Mono Basin during the late Pliocene and Pleistocene". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 114 (8): 991. Bibcode:2002GSAB..114..991R. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(2002)114<0991:DRIMBD>2.0.CO;2.

- "Mono Lake". Long Valley Caldera Field Guide. USGS. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- "Mono-Inyo Craters". USGS. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- "Long Valley Caldera Field Guide - Panum Crater". USGS. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- Ford, T.D.; Pedley, H.M. (1996). "A review of tufa and travertine deposits of the world". Earth-Science Reviews. 41 (3–4): 117–175. Bibcode:1996ESRv...41..117F. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(96)00030-X.

- Dunn, James (1953). "The origin of the deposits of tufa in Mono Lake". Journal of Sedimentary Petrology. 23: 18–23. doi:10.1306/d4269530-2b26-11d7-8648000102c1865d.

- "Tufa". Mono Lake Committee. September 22, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- Dana, ES (1884). A crystallographic study of the thinolite of Lake Lahontan. Government Printing Office.

- Russell, IC (1889). "Quaternary history of Mono Valley, California". U. S. Geol. Survey 8th Ann. Rept. for 1886-1887. pp. 261–394.

- Russell, IC (1883). "Sketch of the geological history of Lake Lahontan". U. S. Geol. Survey 3rd Ann. Rept. for 1881-1882. pp. 189–235.

- Pauly, H (1963). ""Ikaite", a New Mineral from Greenland". Arctic. 16 (4): 263–264. doi:10.14430/arctic3545.

- Council, TC; Bennett, PC (1993). "Geochemistry of ikaite formation at Mono Lake, California: Implications for the origin of tufa mounds". Geology. 21 (11): 971–974. Bibcode:1993Geo....21..971C. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1993)021<0971:GOIFAM>2.3.CO;2.}

- Shearman, DJ; McGugan, A; Stein, C; Smith, AJ (1989). "Ikaite, CaCO3̇6H2O, precursor of the thinolites in the Quaternary tufas and tufa mounds of the Lahontan and Mono Lake Basins, western United States". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 101 (7): 913–917. Bibcode:1989GSAB..101..913S. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1989)101<0913:ICOPOT>2.3.CO;2.

- Swainson, IP; Hammond, RP (2001). "Ikaite, CaCO3· 6H2O: Cold comfort for glendonites as paleothermometers". American Mineralogist. 86 (11–12): 1530–1533. Bibcode:2001AmMin..86.1530S. doi:10.2138/am-2001-11-1223. S2CID 101559852.

- Buchardt, B; Israelson, C; Seaman, P; Stockmann, G (2001). "Ikaite tufa towers in Ikka Fjord, southwest Greenland: their formation by mixing of seawater and alkaline spring water". Journal of Sedimentary Research. 71 (1): 176–189. Bibcode:2001JSedR..71..176B. doi:10.1306/042800710176.

- Whiticar, MJ; Suess, E (1998). "The Cold Carbonate Connection Between Mono Lake, California and the Bransfield Strait, Antarctica". Aquatic Geochemistry. 4 (3/4): 429–454. doi:10.1023/A:1009696617671. S2CID 130488236.

- "Mono Lake FAQ". Mono Lake Committee. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- Jellison, R.; J. Romero; J. M. Melack (1998). "The onset of meromixis in Mono Lake: unintended consequences of reducing water diversions" (PDF). Limnology and Oceanography. 3 (4): 704–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2008.

- Melack, JM; Jellison, R; MacIntyre, S; Hollibaugh, JT (2017). "Mono Lake: Plankton Dynamics over Three Decades of Meromixis or Monomixis". In Gulati, R; Zadereev, E; Degermendzhi, A (eds.). Ecology of Meromictic Lakes. Ecological Studies. Vol. 228. Springer. pp. 325–351. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-49143-1_11. ISBN 978-3-319-49141-7.

- Jellison, R.; Roll, S. (June 2003). "Weakening and near-breakdown of meromixis in Mono Lake" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2008. Retrieved November 13, 2008 – via monolake.uga.edu.

- Benson, LV; Currey, DR; Dorn, RI; Lajoie, KR; et al. (1990). "Chronology of expansion and contraction of four Great Basin lake systems during the past 35,000 years". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 78 (3–4): 241–286. Bibcode:1990PPP....78..241B. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(90)90217-U.

- Stine, Scott (1990). "Late holocene fluctuations of Mono Lake, eastern California". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 78 (3–4): 333–381. Bibcode:1990PPP....78..333S. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(90)90221-R.

- "Monthly Lake Levels". Mono Basin Research Clearinghouse. Archived from the original on February 4, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- "Living in an Alkaline Environment". Microbial Life Education Resources. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- "Frequently Asked Questions About Mono Lake". www.monolake.org. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- "Mono Lake". Ecoscenario. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- "Brine Shrimp". Mono Lake Committee. August 7, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- "Alkali Files". Mono Lake Committee. August 7, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- Shih, Pei-Yin; Lee, James Siho; Shinya, Ryoji; Kanzaki, Natsumi; Pires-daSilva, Andre; Badroos, Jean Marie; Goetz, Elizabeth; Sapir, Amir; Sternberg, Paul W. (September 26, 2019). "Newly Identified Nematodes from Mono Lake Exhibit Extreme Arsenic Resistance" (PDF). Current Biology. 29 (19): 3339–3344.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.024. PMID 31564490. S2CID 202794288. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 9, 2020.

- "Mono Lake". Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- "Birds". Mono Lake Committee. August 7, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- Shuford, David; Page, Gary; Heath, Sacha; Nelson, Kristie (2016). "Factors influencing the abundance and distribution of the Snowy Plover at Mono Lake, California". Western Birds. 47: 38–49.

- LAWTON, HARRY W.; WILKE, PHILIP J.; DeDECKER, MARY; MASON, WILLIAM M. (1976). "Agriculture Among the Paiute of Owens Valley". The Journal of California Anthropology. 3 (1): 13–50. ISSN 0361-7181. JSTOR 27824857.

- "California Indians and Their Reservations: K". SDSU Library and Information Access. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved August 31, 2010.

- Farquhar, Francis (1926). Place Names of the High Sierra. San Francisco: Sierra Club. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- Stewart, OC. "The Northern Paiute Bands" (PDF). Anthropological Records. 2 (3).

- "California Indians and Their Reservations". SDSU Library and Information Access. Archived from the original on July 26, 2010. Retrieved July 24, 2009.

- "Fortieth Annual Report of the Board of Water and Power Commissioners of the City of Los Angeles" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 14, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- "About Mono Lake". Mono Lake Committee. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- "Protecting California Gulls". Mono Lake Committee. October 21, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- "History of the Mono Lake Committee". Mono Lake Committee. Archived from the original on February 6, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- "Dust Sources at Mono Lake". Mono Basin Research Clearinghouse. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- Sahagún, Louis (January 2, 2023). "Conservationists fight to end Los Angeles water imports from Eastern Sierra's Mono Lake". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- Reznik, Bruce (June 27, 2023). "Opinion: A wet winter began to replenish Mono Lake. L.A. should let it be a lake again". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- "State of the Lake". Mono Lake Committee. August 7, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- "Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, 1981.10.1-2". Mono Lake Non-Site (Cinders near Black Point). 1968. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- "Nancy Holt and Robert Smithson, Mono Lake, 19:54 min, color, sound, Electronic Arts Intermix". 1968–2004. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- "Floyd Extra! How Wish You Were Here Went Up In Flames". MOJO magazine. September 2011. Archived from the original on October 13, 2011.

- Twain, Mark (1996). "chapter 38". Roughing It. University of Virginia Library: Electronic Text Center. ISBN 0-19-515979-9. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- Twain, Mark (1996). "chapter 39". Roughing It. University of Virginia Library: Electronic Text Center. ISBN 0-19-515979-9. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- Harris, S.L. (2005). Fire Mountains of the West: The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes. Mountain Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-87842-511-2.

- Twain, Mark. "Roughing it Chapters 38 & 39". Mono Basin Clearing House. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- Harrison, Ken (March 19, 2015). "Mono in the movies: Fair Wind to java". The Sheet.

- Hughes, Howard (2009). Aim for the Heart. I.B. Tauris. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.

- Sweeney, Mike (July 19, 2011). "Don't Know What You Got ('Till It's Gone)". The Huffington Post. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

Bibliography

- Jayko, A.S., et al. (2013). Methods and Spatial Extent of Geophysical Investigations, Mono Lake, California, 2009 to 2011. Reston, Va.: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

- Miller, C.D.; et al. (1982). "Potential hazards from future volcanic eruptions in the Long Valley-Mono Lake area, east-central California and southwest Nevada : a preliminary assessment". U.S. Geological Survey Circular 877. Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey.

External links

- Mono Lake Area Visitor Information

- Mono Lake Tufa State Nature Reserve

- Mono Lake Committee website

- Mono Lake Visitor Guide

- "World Lake Database entry for Mono Lake". Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- Landsat image of Mono Lake

- Roadside Geology and Mining History of the Owens Valley and Mono Basin

_01.JPG.webp)