Lakota religion

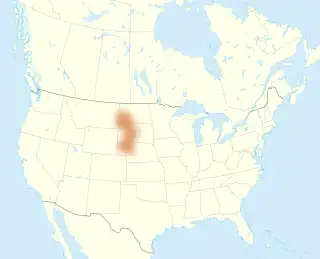

Lakota religion or Lakota spirituality is the traditional Native American religion of the Lakota people. It is practiced primarily in the Lakota reservations of the North American Plains. The tradition has no formal leadership and displays much internal variation.

Central to Lakota religion is the concept of wakʽą or wakan, an energy or power permeating the universe. The unified totality of wakʽą is termed Wakʽą Tʽąką, and is regarded as the source of all things. Lakota religionists believe that, due to their shared possession of wakʽą, humans exist in a state of kinship with all life forms, a relationship that informs adherents' behavior. The Lakota worldview includes various supernatural wakʽą beings, the Wakampi, who fall into different categories and may be benevolent or malevolent. Prayers are given to the wakʽą beings to secure their assistance, often facilitated through the smoking of a sacred pipe or the provision of offerings, usually cotton flags or tobacco. Various rituals are important to Lakota life, seven of them presented as having been given by a benevolent wakʽą being, White Buffalo Calf Woman. These include the sweat lodge purification ceremony, the vision quest, and the sun dance. A ritual specialist responsible for healing and other tasks is usually called a wičháša wakhá ("holy man"). There are various types, the most common being the yuwípi wičháša (yuwípi man), who specialises in the Yuwípi ritual.

One of the three main populations speaking a Sioux language, the Lakota had emerged as a distinct nation composed of seven groups by the 19th century. Many of their religious traditions reflected commonalities with those of other Sioux groups as well as non-Sioux communities like the Cheyenne. In the 1860s and 1870s, the United States government relocated most of the Lakota people to the Great Sioux Reservation, where concerted efforts were made to convert them to Christianity. Most Lakota ultimately converted, although many also continued to practice various Lakota traditions. The U.S. government also implemented measures to suppress traditional rites, for instance banning the sun dance in 1883, although traditional perspectives were documented in the 19th and early 20th centuries by practitioners like Black Elk. Encouraged by the American Indian Movement, the 1960s and 1970s saw revitalisation efforts to revive Lakota traditional religion. In the late 20th century, Lakota practices increasingly influenced other Native American religions across North America.

Many Lakotas practice their traditional religion alongside another, primarily Christianity although sometimes the peyote religion of the Native American Church. Lakota traditions have also been adopted by many non-Natives, the latter a tendency condemned by Lakota spokespeople as cultural appropriation.

Definition and classification

Their name deriving from a term meaning "allies",[1] the Lakota comprise the seven westernmost groups of the Sioux peoples.[2] Other terms for the Lakota include the Western Sioux,[2] Teton Sioux,[3] Tetons,[2] Teton Dakotas,[2] or the Thíthuwa (Prairie Dwellers).[4] The Lakotas had formed into seven subdivisions by the 19th century. The two southern groups are the Oglálas and the Sičháŋǧu, while the five northern groups are the Itázipčho, Húŋkpapȟa, Mnikȟówožu, Sihásapa, and Oóhenuŋpa, sometimes collectively termed the Saône.[5]

Lakota religion has been described as an indigenous religion,[6] and as a primal religion.[7] There is no centralized authority in control of the religion,[8] which is non-dogmatic,[9] with no specific creeds.[10] The tradition is transmitted orally,[11] being open to individual interpretation,[10] and displaying internal variation in its practice.[12] Some practitioners have an attitude of religious pluralism and thus involve themselves in other religious traditions,[13] such as the peyotism of the Native American Church,[14] or alternatively forms of Christianity, especially Roman Catholicism or Episcopalianism.[15] Other Lakotas identify themselves strictly with just one religion,[16] with this particularly the case for Christian fundamentalists.[17] They may perceive some conflict between the two; some Lakota will remove any Christian imagery from a room if a traditional ceremony is to be performed there.[18]

Native American religions have always adapted in response to environmental changes and interactions with other communities,[19] including the encounter with Christianity.[20] This adaptation is evident in Lakota religion, with change being observed since textual records of it were first made during the 18th century.[21] Much of this adaptation is the result of visions experienced by its practitioners,[22] but also from influences coming from other Native American groups like the Cheyenne and the Arikaras.[23] At the same time, tradition is a vital concept for Lakota communities, one that is regularly invoked to legitimate a link between contemporary practices and those of the past.[24]

Among the Lakota, there are difficulties in drawing boundaries between religion and other areas of culture;[25] as is the case with many Native American religious traditions,[26] Lakota religion permeates other areas of life.[27] In the Lakota language, there is no term cognate to the English word "religion",[28] although Christian missionaries active among the Lakota have tried to devise one.[29] Several writers have referred to the tradition as "Lakota spirituality,"[30] reflecting the fact that many Lakotas, like certain other Native Americans, prefer to describe their traditional beliefs and practices as "spirituality", largely as a reaction against the Christian missionary use of the term "religion".[31] The anthropologist David C. Posthumus suggested that the terms "religion" and "spirituality" could be used interchangeably when discussing Lakota traditions.[32] Alternatively, some Lakota prefer to describe these traditions as a "way of life."[32]

Beliefs

Wakʽą and Wakʽą Tʽąką

A key concept in Lakota religion is wakʽą (wakan).[33] This has been translated into English as "holy,"[34] "power,"[35] or "sacred."[36] The anthropologist Raymond J. DeMallie described wakʽą as "the animating force of the universe,"[37] and "the creative universal force."[38] Similarly, the scholar of religion Suzanne Crawford termed it an "invisible energy or life-force,"[39] while Posthumus described it as an "incomprehensible, mysterious, nonhuman instrumental power or energy".[33] Many Lakotas have stressed the incomprehensibility of wakʽą;[40] the Oglála man Good Seat described wakʽą as "anything that was hard to understand."[40] The term wakʽą also has connotations of being ancient and enduring.[41] Ideas similar to the Lakota wakʽą are evident in the orenda of the Iroquois, the manitou of the Algonquian peoples, and the pokunt of the Shoshone.[42]

Displaying a holistic view of the universe,[43] Lakota religionists believe that wakʽą flows through the cosmos, animating all things,[33] and that all beings thus share the same essence.[13] It incorporates evil aspects of the universe, described as wakan šica ("evil sacred").[44] The universe is deemed to exist in a harmonious balance,[45] although is considered fundamentally incomprehensible and beyond humanity's ability to know it fully.[46] In Lakota, objects or people who are imbued with wakʽą force can also be termed wakʽą.[39] Practitioners of Lakota religion hold that humanity can share in wakʽą through ritual.[37] Both wakʽą itself, and the rituals that pertain to it, are considered to be wókʽokipʽe (dangerous),[47] with Stephen E. Feraca, who worked at Pine Ridge, relating that in Lakota religion, "fear and respect" were "virtually indistinguishable."[48]

The unified totality of wakʽą is termed Wakʽą Tʽąką (Wakan Tanka),[49] a term translated as "the Great Mysterious,"[17] "the Great Mystery,"[50] "the great holy,"[51] "great incomprehensibility,"[37] or "the sum of all things unknown".[39] DeMallie described Wakʽą Tʽąką as "the sum of all that was considered mysterious, powerful, or sacred".[37] Wakʽą Tʽąką is deemed to be eternal, both creating and constituting the universe.[37] The term Wakʽą Tʽąką has been used as a Lakota translation for the English word "God", including by Christian missionaries,[52] with some Lakota equating Wakʽą Tʽąką with the Christian deity.[53] Although the scholar of religion Åke Hultkrantz suggested that Wakʽą Tʽąką could be regarded as "a personal, delimited Supreme Being",[51] various other scholars have cautioned that Wakʽą Tʽąką was unlikely to have been seen as a personified divinity prior to the influence of Christianisation.[54]

Wakampi

The Wakampi are beings made from wakʽą.[55] The anthropologist William K. Powers characterised these as "supernatural beings and powers,"[56] although Lakota belief draws no distinction between the natural and the supernatural,[57] the latter being a European-derived category.[58] These wakʽą beings are eternal,[59] and play a role in creating and controlling the universe.[56] Morally ambiguous in their approach to humanity,[60] they can behave either benevolently or malevolently to humans.[61] Lakota religionists show them respect by referring to them with the honorific terms tʻukášila or thukášila ("paternal grandfather") or ųcí (grandmother), terms which also invoke a family relationship.[62]

There is much variation in how Lakota religionists classify the wakʽą beings, as these classifications can be rooted in individual visions and experiences.[38] One approach is to divide them into 16 groups, arranged hierarchically into groups of four: the Wakan akanta, the Wakan kolaya, the Wakan kuya, and the Wakanlapi.[63] The former two groups are considered to be Wakan kin ("the sacred"); the latter two called Taku wakan ("sacred things").[63]

The Wakan akatna or "superior wakan" comprise four primordial characters: the sun, Wi, the sky, Škan, the Earth, Maka, and the rock, Inyan.[63] The Wakan kolaya, or "those whom the wakan call friends or associates", include the moon, Hanwi, the wind, Tate, the falling star, Woĥpe, and the thunder-being, Wakinyan.[63] The Wakan kuya are the "lower, or lesser, wakan", and include the buffalo, Tatanka, the two-legged (including both bears and humans), Hununpa, the four winds, Tatetob, and the whirlwind, Yumni.[63] He Wakanlapi, "those similar to wakan", include niyá, nağí, and the šicų, the eternal inner components of a person.[63]

There are also groups of spirits who inhabit specific parts of the universe.[64] These include the Unkteĥi water spirits, the Unkcegila land spirits, the Canoti forest spirits, and the Hoĥogica lodge spirits.[64] These spirits are potentially dangerous to humans and so are warded off through specific rituals and the aroma of sweetgrass and sage.[64]

The Wakinyan oyate or thunder beings are spirits of thunder and lightning deemed to live in the west.[65] They are generally benevolent, thought capable of ridding evil with their cleansing rains.[65] Linked to these spirits are the Heyoka kaga, deceased men who dreamt of thunder and lightning and ultimately became invisible to other humans.[66]

Neither specifically malevolent of benevolent to humanity is Inktomi, the spider,[56] a figure presented as being both human and non-human.[64] He takes the role of a culture hero in Lakota lore,[56] and is thought to play tricks on people.[67]

Cosmogony

A common origin story among the Lakota begins with Iyan (Rock). This Iyan opened up and the blue Mahpitayo (Sky) and green Maka Ina (Earth) bled from it, but were initially without motion. Iyan then opened again and released its spirit, taku skan skan, which imbued Mahpitayo and Maka Ina with life.[68] Together, Mahpitayo and Maka Ina then created Taté (Wind), Anpetu Wi (Sun), Hanhepi Wi (Moon) and the Pté Otayé (Buffalo Nation), who were the first people,[68] as well as the ancestors of the Lakota.[69] The first members of the Pté Otayé were Wazi (Old Man) and Wakanka (Old Woman), and they had a daughter, Ité, who then married Taté, giving birth to East Wind, West Wind, North Wind, South Wind, and Whirlwind.[70]

The trickster, Iktomi (Spider) then convinced Anpetu Wito to fall in love with Ité, encouraging them to sit next to each other, breaking established decorum. To deal with the problem, Mahpitayo ordered Anpetu Wi and Hanhepi Wi to keep from each other, resulting in the sun and moon appearing at different times. Wazi, Wakanka, and Ité were banished to wander the earth, while the rest of the Pté Otayé remained in the spirit realm.[68] Lonely on earth, Ité – who was now renamed Anog-Iné – conspired with Iktomi to lure other members of the Pté Otayé to join her. Seven couples from the Pté Otayé entered the earth in the midst of a harsh winter, where they were taught how to survive by Wazi and Wakanka.[71] The seven couples established the seven sacred fires, or Oceti Šakowin, of the Pté Otayé.[71]

The Pté Otayé on earth lived a harsh existence, and one winter were desperate for help. Two young men encountered a woman on the Plains, White Buffalo Calf Woman. One of them men lusted after her and sought to rape her; a mist arose and the man was reduced to bones. The other man treated her with respect, and she went on to teach his people how to use the sacred pipe, to perform seven ceremonies, and how to hunt buffalo.[72] Lakota tradition holds that the White Buffalo Calf Woman will one day return to them from the east.[73]

Spirit and afterlife

Lakota religion draws a clear distinction between the physical body and a spiritual interior.[74] It holds to a triune conception of the human spirit or soul, comprising the niyá, nağí, and the šicų.[75] The niyá is the life or breath; the nağí is the spirit or soul; the šicų is the guardian spirit.[75] These are the wakʽą aspects of a person and are therefore immortal.[75] Also important to a person's identity is the wacʽį (mind, will, consciousness), the cʽąté (feelings, emotions), and the wówaš'ake (strength, power).[75]

Lakota religion teaches that the niyá is given to a person at birth by the sky, Táku Škąšką ("Something that Moves").[76] The niyá is believed to live on after bodily death as an immaterial thing, likened to smoke or a shadow.[76] The nağí retains a person's idiosyncrasies.[77] The šicų is a non-human potency or influence, believed to have been given to a person by Táku Škąšką.[77] After bodily death, it returns to the nonhuman person or star from which it originally came.[77] A human may also acquire additional šicų in life, mainly through visions and dreams.[77]

Afterlife beliefs vary among the Lakota.[78] Some practitioners belief that the deceased continue to reside near their living kinsmen; others hold that the dead move on to an afterlife world that is similar to the world of the living.[78] A spirit may remain and haunt a particular place, such as its former house or the tree in which it was buried.[79] Ghosts of individuals who died unsatisfied are particularly prone to haunting the living; these may be appeased through ritual interventions.[80]

Animism

Lakota tradition holds that animals, spirits, rocks, trees, and medicine bundles are all persons with their own souls.[81] Posthumus argued that this makes the religion animistic.[82] Due to the underlying shared interiority of all beings, Lakota lore holds to the possibility of physical metamorphosis.[83] In Lakota myth, the Wakíyą can take the form of both birds and humans, while the Buffalo People similarly can take either buffalo or human form.[84] Prominent mythological figures can also take different forms; White Buffalo Calf Woman for instance appears as both a buffalo cow and as a young woman.[85]

The šicų is deemed to be present in both animate and inanimate objects, as well as in supernatural beings and powers.[86] A person may acquire many šicų; in Lakota belief, this is how holy men increase their power.[86] Sacred bundles are a foci for ritual activity.[87] Lakota traditionalists may place objects into a bundle that are based on images they have received in a vision.[87] For practitioners, these bundles are not regarded as being purely symbolic, but rather are "material manifestations of sacred power."[87]

Stones are also deemed capable of having their own niyá and being animate; Lakota lore teaches that they can move of their own accord, dance, communicate with humans, and produce sparks or blue light.[88] Certain stones, usually small and spherical or egg-shaped ones, are believed to possess particular power.[89] These stones are regarded as being inhabited by a šicų spirit that has its own personal name.[90] The šicų is invited into the stone through a ritual called the cʻaštʻų,[88] or the Inktomi Iowanpi (Spider Sing).[91] These stones are often referred to as a thuká, an abbreviation of the term thukášila, or alternatively as íya wakhá (holy stones).[92] Šicų-inhabited stones are deemed to protect their keeper,[93] and contribute to the latter's power.[88] They are worn if a person is engaged in an important task or is in need of assistance from spirit beings.[90] The bundle in which these stones are usually kept is called the wašícų tʻųká.[94] Although generally supposed to be kept in the bundle when not in use, this is not always adhered to – Feraca encountered a large example which was used as a doorstop.[92]

Kinship

Due to the unifying presence of wakʽą,[47] in the Lakota worldview all life-forms as thought to be related,[95] thus having reciprocal obligations and responsibilities to one another.[96] Lakota religionists express this notion with the saying mitákuye oyás’į (Mitakuye Oyasin), meaning "all my relations" or "relatives all",[97] something often repeated at ceremonial and social gatherings.[98] Humans—who in Lakota are called Wicaša akantula ("men on top")[37]—are deemed to be connected to all other living things through these bonds of kinship.[45] Feraca described Lakota religion as "very strongly kinship oriented",[99] while Posthumus suggested that kinship is "the dominant interpretative principle of Lakota culture".[47]

In Lakota belief, each species forms its own oyáte, a people, nation, or tribe.[100] The oyáte categories are based on physical attributes, for instance the two-legged, the four-legged, the winged, those who swim, those who crawl, and those who burrow.[101] There are further subdivisions within these categories.[101] Each oyáte is regarded as having its own kinship rules, with its own warriors, hunters, holy men, and leaders.[102] The Zįtkála Oyáte (Bird Nation), for example, is led by Wąblí Glešká (Spotted Eagle).[102] Like human groups, the oyáte do not always interact peacefully with each other.[101] There is for instance a war between Ųktéhpi (Horned Water Spirits) and the Wakíyąpi (Thunderbirds).[103]

Lakota religion does not present humans as being superior to other lifeforms.[104] Instead, humans are perceived as the least knowledgeable and least powerful of beings, requiring the aid and pity of other entities.[105] Lakota mythology holds that humans have learned much from other animal species.[106] The buffalo play a central role in traditional Lakota cosmology. They are regarded as being relatives of the Lakota and a source of life, having historically provided the meat and hide that Lakota used for food, clothing, and shelter.[107] Traditionally, the hunting and butchery of buffalo had ceremonial elements.[107]

Cosmology and the Sacred Hoop

The anthropologist Luis Kemnitzer noted that, for Lakota, land offers a "religious-historical sense of place and continuity."[108] Disrespect to the land is seen as an affront to Lakota spirituality.[109] In the Lakota worldview, there are six directions, each with an associated color: west (black), north (red), east (yellow), south (white), the earth (green), and the sky (blue).[110] The cross symbolism involving turning to the four directions is acted out in procedures such as the smoking of the pipe or the vison quest.[111]

The Sacred Hoop, or cangleska wakan, is historically conceived as a camp circle formed by a ring of tipis.[112] At some point, it came to symbolise the idea of all nations living in harmony,[112] as well as the notion that all life is connected,[113] including humanity's relationship with the buffalo and the wider universe.[45]

Morality and gender roles

The anthropologist Beatrice Medicine referred to four main virtues among the Lakota: sharing and generosity, fortitude, wisdom, and bravery.[114] The traditional Lakota concept of wolakota refers to living life in a manner that maintains a balanced relationship with other entities.[107] Crawford noted that to "assure personal and communal health," it is important for Lakota traditionalists to honor their relatives, remain faithful to their bonds of kinship, and to affirm relationships with the cosmos and to wakʽą forces.[87] It has been argued that the Lakota traditional belief that all things are kin has contributed to a conservationist ethos among 21st-century Lakota.[115]

Lakota culture features a notion of imminent justice or retribution termed wakhúza.[116] Feraca described the traditional Lakota worldview as being fatalistic.[116]

Traditional Lakota society clearly defines and separates the roles for men and women,[117] with Medicine referring to the "complementarity of the sex roles in Lakota life".[118] In Lakota religion, the quest for knowledge of wakʽą has been a largely male concern.[117] While menstruating, women are prohibited from certain rituals like the yuwipi, with tradition maintaining that their blood would offend the spirits.[119] During menstruation, women were historically expected to retreat to the išnatipi ("to live alone"), away from other community members.[120] Historically, the winkte ("would-be woman") were males who experienced dreams of a wakan woman or the pte winkte hermaphroditic buffalo cow, and thus adopted the social role of women, sometimes marrying men. The winkte were responsible for naming children.[121]

Practices

Both public and private rituals permeate traditional Lakota life.[122] While some Lakota have emphasised the importance of correct procedure, others have said that a practitioner's intention is the most important part of a rite.[123] Some scholars have described Lakota traditional ceremonies as being culturally conservative.[124] DeMallie argued that ritual is more standardised than belief in Lakota religion,[117] and that the incorrect performance of a rite according to custom can be seen as invalidating it and potentially causing harm.[117] Conversely, Feraca observed a "lack of rigid standardization in Lakota ceremonialism."[125]

The right to lead a ceremony is typically deemed to derive from oral transmission from elders, from personal visions, or from an act of self-sacrifice such as fasting.[126] Lakota will often believe that the authenticity of the rite derives from its following of protocol as well as the ethnicity of the person leading it;[127] Lakota practitioners disagree on the extent to which non-Native Americans can participate in such rites.[128] The place of distinct sex roles during ritual has also been an issue of increasing debate among Lakota communities since the mid-20th century.[129] Generally, menstruating women are asked not to attend ritual.[130]

The ceremonies are designed to achieve and maintain a state of wolakota, meaning balance or harmony.[39] Participants will usually remove shoes for ceremonies, as a sign of humility.[131] According to a tradition recorded by Black Elk, seven of these rites were taught to the Lakota by White Buffalo Woman:[132] the wanagi’yu hapi funerary rite, the isnati ca lowan rite of passage for girls, the tapa wankayeyapi ball game, the inipi sweat lodge, the hanble’ceya vision quest, the hunkapi adoption ceremony, and the wi’wanyang wacipi sun dance.[133]

Prayer and offerings

Through ceremony, the [Lakota] sought to (re)establish relationship and to placate, and appease ambiguous, powerful, and often frightening and dangerous spirits. Generally, they wanted to be left alone, free of anxiety, misfortune, sickness, and death. Honoring, respect, and reverence[...] are more appropriate from [Lakota] perspectives than worship.

— Anthropologist David C. Posthumus[60]

The Lakota term wacʽékiye (wacekiye) denotes prayer, but also means to call on someone's aid or to claim a relationship with them.[134] In Lakota religion, prayer thus entails invoking a relationship with wakʽą beings, encouraging them to live up to the generosity expected of them as kin.[45] Also part of wacʽékiye is the need to appear pitiful before the spirits,[135] with Lakota prayers commonly featuring the expressions "pity me" and "pity us".[136] For Lakota, prayer is also about placating the spirits and showing them respect.[60] It usually entails a ceremonial crying or wailing, followed by lifting the arms up with palms outstretched and then putting them towards the ground in a sign of respect and gratitude.[137]

A sacred space for communicating with the spirits is termed hocoka.[138] These are not permanent spaces and ceremonial rules only apply for the duration of the ritual;[139] DeMallie noted that no "sharp distinction" is made between the sacred and the profane in Lakota tradition.[140] Bison skulls are often used as temporary altars, as are rocks or boulders typically painted with red earth.[141] Offerings to the spirits may also be tied to trees,[142] left at the base of a tree,[143] or placed on hillsides.[144] These places become means through which to communicate with wakʽą.[141]

Cloth flags erected as offerings are called a wa’úyapi (wanunyanpi; "offerings").[145] These became prominent at a time when cloth was a highly esteemed item among Lakota communities.[146] The flags appear in different colors, each representing a cardinal direction: black (west), red (north), yellow (east), and white (south).[147] For certain rituals, like the yuwípis, two additional flags may be used: green (earth) and blue (sky).[147] Small bits of tobacco are often tied in one corner of the cloth.[148] The Čhalí wapháĥta ("tied tobacco pouches") consist of small squares of cloth that contain a few grains of tobacco.[149] The spirits are believed to take the essence of the tobacco back to their homes.[138] Sage is often employed in Lakota ceremonies;[150] it is deemed sacred to wakʽą beings,[151] with the spirits enjoying its aroma.[152] As well as being used in prayer, it is burned for purification and tied into bundles given as offerings.[153] Those picking leaves will often request permission from the plant before doing so.[153]

Suffering is an important element of Lakota religion.[154] The sincere suffering of an individual during ritual is believed to attract the spirits' attention while also mediating the broader suffering of the community.[154] As most people are deemed to have nothing to offer to the wakʽą forces but their own bodies, the sacrifice of a person's own flesh is deemed appropriate.[65] In some ceremonies, participants cut small pieces of flesh out of their arms or legs, which are then offered to the spirits, especially if the supplicant wishes to get the spirits' aid in healing a sick person.[155]

Dog sacrifice is also practiced in Lakota religion,[156] an act generally seen as repugnant by many other Native American groups and European Americans.[157] One explanation given for this act is that the dog's spirit will receive a vision, which it can then relay back to a ritual specialist.[158] The sacrifice usually entails a puppy being selected, sometimes painted, and then strangled to death with a rope, after which its flesh will be prepared as the main dish of a religious feast.[159] Once the dog meat is boiling in a pot, a ceremony called the Heyoka kaga is performed. This entails people dancing around the pot while singing songs to the heyoka spirits, plunging their hand into the boiling water intermittently. They then use forked sticks to try and remove the meat, which is subsequently shared and eaten.[160] Other dishes traditionally eaten at Lakota feasts include the wahanpi buffalo or beef stew, a chokeberry dish called wojapi, and frybread.[161]

The Sacred Pipe

An important sacred object for the Lakota is the chanupa or pipe.[162] It usually consists of a hollow wooden stem attached to a catlinite bowl.[162] Catlinite is quarried from near Pipestone, Minnesota; the Lakota term this iyanša (red stone), for in their mythology it formed from the blood of a people killed in a primordial flood.[163] Additional material, such as eagle feathers, may be attached to the pipe.[162]

Smoking the pipe is a means of prayer;[17] the Lakota word for pipe smoking and for prayer are both wacʽékiye.[164] The substance smoked, kinnikinnick, is a blend of various herbs, but primarily cancasa, the inner bark of red ossier dogwood.[165] Practitioners believe that smoking renders their prayers more powerful and effective,[87] for the smoke takes the prayers directly to Wakʽą Tʽąką.[166] The smell is deemed pleasing to benevolent spirits and off-putting to malevolent ones.[165]

Pipe smoking ceremonies were historically found among various Plains peoples.[167] Among the Lakota, it is integral to most major rituals, although is not regarded as one of the seven rites given by White Buffalo Woman.[167] In Lakota pipe smoking ceremonies, the pipe will be unwrapped, assembled, and then held aloft to each of the four directions while prayers are offered. It may also be passed around all assembled persons, so that each may pray in turn.[168] Those menstruating are barred from smoking.[169] When not in use, the pipe will be dissembled into its bowl and stem so as to limit its power and potential danger arising from that.[170]

Any Lakota may possess a pipe, but there are certain examples, owned by particular families, that are well-known and highly regarded.[168] The most important for the Lakota is the Buffalo Calf Pipe or Ptehícala Čhanúpa.[171] This is the community's "most sacred possession," described as "the very soul of their religious life".[172] In Lakota tradition, the Calf Pipe was given to the Lakota by White Buffalo Woman.[173] Many Lakota attribute much of their community's traditional religion to the acquisition of this pipe,[174] sometimes believing that all other pipes originate from it,[175] or derive their power from it.[176] The Buffalo Calf Pipe is kept within a sacred bundle and entrusted to a keeper within the community.[172] The scholar of religion Suzanne Owen called the Pipe's keeper "one of the most important roles among the Lakota".[123] For several generations the Pipe has been in the custody of the same family, residing at Green Grass Village on the Cheyenne River Reservation in South Dakota.[177] Before the keeper dies, they will pass the task on to a blood relative, a decision they are guided to make through visions.[11] The Sacred Calf Bundle will be opened for ceremonies on special occasions.[178]

Sweat lodge

A basic preparation before Lakota rituals is the ini kaġapi ("they revitalize themselves"), a period of time spent in a purification lodge or sweat lodge.[179] A shorter variant of this process is often termed the inípi.[180] This is deemed a time for prayer.[181] Although intended to cleanse or purify a person's body and spirit in readiness for a ritual,[179] it can also be carried out for its own sake, rather than as a preparation for another rite.[182]

The sweat lodge itself is called the iníthi.[180] This is the only permanent religious structure used in Lakota religion,[183] and is often situated close to a practitioner's home.[180] The iníthi is typically made from willows bent into a framework, usually around six feet in diameter and four feet in height. The entrance may face either the east or west.[180] The structure typically resembles a round dome.[154] Participants may tie offerings of cloth or tobacco to the willow framework.[184] When in use, a canvas will be draped over the outer frame.[185] Close to the iníthi will often be found an earthen mound representing the Earth,[180] or an altar featuring staffs to which offerings may be tied.[186]

While there is a general framework behind the sweat lodge ritual, each performance will be unique.[187] A fire will be lit outside the lodge; ceremonies sometimes accompany the gathering of firewood and the lighting of this fire.[180] Once the participants have entered the iníthi, one person may stay outside, the thiyópa awáyąke (doorkeeper).[188] Stones heated on the fire are then placed in a pit at the centre of the lodge. Water is poured onto these stones, producing steam.[189] Cedar may also be sprinkled onto them to create an aroma.[188] The interior becomes extremely hot;[190] the endurance is seen as a means of suffering to secure prayers to aid others.[191] The interior of the lodge is largely dark;[191] sparks seen on the rocks, or sounds heard, are often considered spirit manifestations.[192] The men who meet inside the sweat lodge are typically naked.[193] Participants will offer prayers and songs, also rubbing and slapping themselves with sage.[194] A pipe may be smoked, in which case it will be passed clockwise so that everyone can smoke in turn.[195] Once the ceremony is over, the participants leave the lodge and dress,[196] sometimes sharing another smoke and a meal.[197]

Vision quest

In Lakota, a vision quest is called a habléčheya ("crying for a dream/vision").[198] According to Feraca, this is "one of the core elements of Lakota religion."[199] In Lakota, the term hablé applies to a dream or vision, although in traditional culture a distinction is usually made between an unsought dream and a vision pursued through a habléčheya.[200] In Lakota culture it is thought that anyone, regardless of gender, may undertake the habléčheya to gain advice from the wakʽą beings.[201] While both men and women now undertake the quest, there are debates as to whether that was the case historically;[202] 19th-century records only describe male experiences with vision questing.[117]

Prior to a habléčheya, an individual may undergo purification in the sweat lodge, sometimes with an older mentor.[203] They will then depart to an isolated place, usually upon a hill, to spend time alone in the hope of receiving a vision.[204] During this period, the seeker will be largely naked and have their hair un-braided as a sign of humility to the spirits.[205] This is to ensure that they are pitiable to the spirits and the latter will hear the supplicant's prayers.[151] They will fast, although a small quantity of water may be permitted them if staying for multiple days.[206] Often, they will stand and sleep on a bed of sage;[205] they may also have, and smoke, a filled pipe for prayer.[207] Offerings of cloth flags and tobacco may be tied to poles positioned in the four directions, marking the space as wakʽą.[208] A buffalo skull altar may be placed in the west corner.[154] The vision seeker may remain there for as long as four days and nights.[209] A mentor may visit them daily, although passers by are expected to ignore them.[206]

The content of the vision is often unique, however there are also recurring motifs among Lakota visions, such as the presence of a tipi in the clouds.[38] Receiving a vision gives the vision seeker a wakʽą quality that sets them apart from other people.[210] It provides the vision seeker with knowledge and often powers to heal the sick, which they will then be obliged to use to help people.[210] After the vision, the seeker may return to their community and undergo another sweat lodge ceremony, during which they may discuss their vision with their mentor.[211] Some of those taking part in the habléčheya give up without receiving a vision.[206] Those who fail are often accused of breaking their fast or of being morally unfit to receive a vision.[201]

Sun dance

The Lakota sun dance is termed the Wiwáyag Wačípi ("sun gazing dance" or "gazing at the sun").[212] It derives from the Cheyenne medicine lodge ceremony;[213] the Cheyenne called these ceremonies "sun dances", although unlike the Lakota version these did not entail dancers staring at the sun.[214] It is unclear when the Lakota developed their sun dance,[215] although scholar of religion Åke Hultkrantz argued that the rite spread through the Plains no earlier than the 18th century.[216] It was present among the Lakota by the 19th century, when it was "essentially a warrior ceremony," performed to secure success in battle or to capture horses, or to fulfil a vow in thanks for a previous success.[215] The Oglalás were then instrumental in diffusing the sun dance among other Plains groups.[213]

The modern sun dance is organised by a committee who select the date, pick a director, and arrange for publicity and the maintenance of the grounds east of Pine Ridge Village, where the ceremony takes place.[217] The dance itself takes place in a purpose-built dance lodge, consisting of two concentric circles of posts. Between the inner and outer rings, pine boughs or plywood forms a protective roof to create areas of shade where the spectators sit. The inner circle is left open to direct sunlight.[218] In the inner circle, a central pole, the čhawákha ("holy tree"), is erected.[219] It is made from a wáğačha, or cottonwood tree, which is stripped of its branches except at the top.[220] Specific customs are observed while cutting this tree, with the first cuts being made by virgin girls;[221] the pole is not supposed to touch the ground until being erected in the dance lodge.[222]

After being erected, the čhawákha is honored with songs, smoke from a sacred pipe, and prayers to the four directions.[223] While the decoration on the čhawákha varies, it typically features a red cloth banner and a brush bundle tied near the top,[148] the latter an offering to secure the supply of wild plant foods.[224] Also commonly added to the čhawákha are rawhide images of a human or buffalo figure,[225] cloth streamers and tobacco bundles.[226] A buffalo skull will often be at the base, with an altar set up nearby.[227] Near to the dance lodge, a sweat lodge and tipi will also be erected in advance of the ceremony.[219]

The sun dance has always seen variation,[228] and no two sun dance ceremonies are identical.[229] On the night before the dance, a feast will often be held, while some people will stay up around a fire all night, drumming and singing.[230] The dancers will sleep in the tipis, where the floors will be covered in sage.[231] The dancers form part of a procession who come from the tipi to the centre of the dance lodge, carrying a buffalo skull.[232] They circle the čhawákha clockwise, before placing the skull on the west side of the lodge. Prayers will often be said, and the dancers then face toward the sun.[213] They may face the sun, or alternatively the four directions, or the čhawákha.[229] The dancers will often bob by their knees while remaining standing in one location,[213] although will sometimes dance around the pole.[233] Throughout, the dancers are expected to pray,[233] blowing repeatedly on eagle ulnar whistles.[234] A group of singers will perform accompanied by drumming.[234]

The sun dance is intended to facilitate communal renewal through the sacrifice of the dancers.[235] Many dancers physically pierce their skin during the ceremony, although the manner in which this occurred varies. A more basic form included cuts being made on the dancers' limbs.[214] Other instances involved thongs being affixed to the dancers back or chest muscles, often on sticks skewered through their flesh. These thongs were then attached to a rope that would be attached to the čhawákha.[236] Often, the piercings will tear free from the dancer's body during the dance.[237] Some of those who dance for several days choose to only pierce during one of them, although others remain pierced for each day.[238] On occasion, the rope will instead be attached to a group of buffalo skulls which will then be dragged around the circle by a dancer.[239] Some of the spectators, including women and the elderly, sometimes also provide flesh offerings during the ceremony.[240]

Further rites

The Isnati Awicalowan is a coming of age ceremony for young women.[202] When a girl first menstruates, she is placed in seclusion for four days, during which older women will teach her women's tasks, including cooking, basketry, weaving and beading.[241] A sponsor, who is often the girl's grandmother, will symbolically take on the role of White Buffalo Calf Woman during this ritual.[242] Once the rite is over, the girl is considered to have become a woman.[242] Her family then hold a feast and give gifts away to others.[242] Medicine suggested that the habléčheya ceremony offered a comparable coming of age rite for males.[118]

When a person dies, their family may hold a mourning ceremony, the Wanagi Yuhapi.[242] A lock of hair is taken from the deceased and kept for a year, cared for as it is considered to hold the person's spirit. During that year, the family must observe specific etiquette. At the end of the year, mourning songs and prayers are offered and the hair is burned. The family will then hold a feast and give away gifts.[242] Objects belonging to the deceased may be given away to prevent their soul continuing to lurk around their possessions.[79] Traditionally, corpses were placed in trees or on purpose-built scaffolds.[243]

The Hunkapi lowanpi is an adoption ceremony in which new kinship relations are established with somebody,[202] sometimes allowing the integration of non-Lakota people into Lakota families.[244] Historically it has played an important role in keeping peace between communities.[202] According to Black Elk, the first Hunkapi lowanpi was held between the Lakota and the Arikara, having been given to the Lakota holy man Matohoshila (Bear Boy) in a vision.[244] In some versions of this ceremony, songs are sung over the individual being adopted and a pipe stem is waved over them.[202] The adopted person will be given a new name, and they are then given dried meat and cherry juice to consume.[202]

Healing and cursing

Healing is an important part of traditional Lakota religion.[245] By at least the latter half of the 20th century, a common belief among Lakota people was that their ancestors experienced no serious ailments prior to the move onto the reservations.[246] Traditional healing practices are often the most popular alternative to Western medicine among Lakota.[247] Many modern Lakota favor traditional medicines;[248] they may regard them as being more powerful,[249] mistrust European American doctors,[249] or fear being hospitalised away from their family.[250]

Anyone with knowledge of traditional healing methods is termed a wupiye ("one who heals/mends" or "doctor").[247] The wupiye can often be divided into two groups, the pejutu wicušu/winyelu ("medicine man/woman") whose healing procedures do not necessarily invoke supernatural assistance, and the wičháša wakhá ("holy man"), who invokes such entities as helpers.[251] When herbs are collected for use in healing practices, it is expected that a small quantity of tobacco will be given in exchange, scattered by the plant or buried beneath it.[247] The herbs collected will then be kept away from any menstruating woman.[247] In rites where spirits are invoked for a healing purpose, these entities might stipulate certain instructions that the patient must then follow.[252]

A wičháhmuğa ("bewitcher", "witch") describes a person who uses supernatural powers to purposefully harm others.[253] It is feared that these individuals can kill with incantations,[254] pervert the ton of things such as water so that they become harmful,[255] and turn humans into other animals.[254] Between the 1970s and 1990s, fears about witchcraft became a growing presence in Lakota reservations.[256] Certain animal species are also deemed capable of causing humans supernatural harm.[80]

Holy Men

.jpg.webp)

The term wičháša wakhá ("holy man") describes those in Lakota society who serve a healing function.[257] Most provide a range of functions, including healing, counselling, locating missing persons or objects, predicting the future, directing ceremonies, and conjuring.[258] Lakota people sometimes use English-language terms for these specialists, such as "doctor" and "medicine man," although these are used loosely for the benefit of non-Lakota speakers.[257] Other English language terms that have become popular among Lakota since the 1960s have included "holy man", "spiritual leader," "spiritual advisor" and "mentor".[259] The term waphíye wičháša ("doctor man") is sometimes applied to any ritual healer, but is often reserved for those who practice herbalism without any ceremonial conjuring.[260]

Holy men derive their powers of interpretation from their communing with supernatural forces.[78] In Lakota traditional culture, it is believed that an initial dream will often set a person on the path to becoming a ritual specialist. They might then consult an experienced elder about their dream, and the latter may often urge them to undertake a vision quest.[261] Once the vision quest is over and they have received a dream, the seeker may start training as a ritual specialist under an experienced practitioner.[262] It is believed that during the vision, a wakʽą being may instruct the vision-seeker in a particular ceremony, the use of herbs, or some other religious skill.[263] The vision may also lead to taboos being imposed on the dreamer, for instance that they must not fall in love or keep money rendered for their services.[264] Holy men become conduits through which wakʽą flows,[55] but they cannot completely control this force.[264] Many stories of ritual specialists using trickery circle in Lakota communities; some believe that this makes these individuals frauds, although other Lakota regard a certain element of trickery as being part of the performance.[265]

These specialists gain contact with Wakampi through dreams or visions,[55] and are expected to undergo vision quests at least annually.[266] It is believed that they gain new knowledge and new power through each vision, possessing more šicų. The more šicų a specialist has, the more powerful their ceremonies are believed to be.[267] At the same time, growing power means the holy man poses greater potential danger both to himself and to those around him.[266] By helping others, the holy man gives away some of his šicų, ultimately weakening him.[268] By the time they are elderly, they are regarded as being largely without power, and may be subject to ridicule and mistrust.[269] Their ritual paraphernalia is often destroyed when they die.[269]

Someone seeking the assistance of a ritual specialist will approach them with a pipe and tobacco, an offering termed the opaĝi, at which the specialist will then decide whether they will help.[270] If the holy man feels that the afflicted person is being punished for a misdemeanour then they may refuse to assist them.[116] If they accept the task then they will give the client instructions.[271]

Yuwípi and yuwípi wičháša

In his repetition of Lakota themes and values, the yuwipi practitioner reaffirms and strengthens tribal identity. The recounting of myths and songs, the repeated testimonials, the emphasis on the unity of the living, the departed dead, and the historical heroes, all forge stronger links between the participants in yuwipi ceremonies and help them glory in their differentiation from off-reservation culture.

— Thomas H. Lewis, 1987[272]

Another Lakota rite is the yuwípi, the name of which means "they wrap him" or "to wrap".[273] This is a type of ceremony known widely among Plains and Woodlands Native groups, bearing close similarities with the Ojibwe and Cree tent-shaking rite.[274] A client may sponsor a yuwípi to request the spirits assist with healing, retrieving lost objects, dealing with legal problems, or as a thanksgiving to a task already accomplished by the spirits.[275]

Among the Lakota, the yuwípi is conducted by a specialist called the yuwípi wičháša (yuwípi man),[276] a figure who may also call himself an iyeska ("interpreter, medium").[277] The yuwípi wičháša does not wear distinctive clothing,[278] although is typically accorded respect with the honorific term thukášila.[277] They are typically called to the profession through visions, after which they are apprenticed to an existing practitioner.[277] On taking on the role, they are expected to revitalise their powers through regular vision quests, handle their sacred pipe correctly, and avoid menstruating women;[279] should their ritual paraphernalia come into contact with a menstruating woman it is believed that it will lose its efficacy.[280] Yuwípi wičháša often also utilise stones containing a šicų spirit.[281]

Having previously undertaken a sweat lodge ceremony,[282] the yuwípi wičháša will go to the place where the yuwípi is being held and set out objects to demarcate the ceremonial hocoka area. At one end will be the makhákağapi ("made of earth"), an altar of soil, usually taken from underground rather than the surface to ensure it has not been polluted by humans.[283] The yuwípi wičháša will be alone inside this ceremonial area; the spectators remain outside, where they may sit or dance in-place.[284] Each may wear a protective sprig of sage;[285] some attendees will offer pieces of their flesh, typically then placed in a rattle.[65] During the rite, participants often sing or drum to call the spirits.[286]

Tunkasila wamayank uye yo eye

Tunkasila wamayank uye yo eye

Mitakuye ob wani kte lo eye ya

hoyewayelo eye ye.

Grandfather, come to see me.

Grandfather, come to see me.

So that my relatives and I will

live, I am sending my voice.

— A yuwípi song[287]

The yuwípi wičháša will often be tied up with rope or leather thongs, sometimes wrapped within a quilt.[288] While bound, they will seek visions from the wakʽą spirits.[289] With the room in darkness, he will announce the names of spirits that he claims have arrived in the space, and spectators can then give him questions and prayers to relay to the spirits.[290] He will also encourage the spirits to heal anyone with ailments.[291] The shaking of rattles is deemed to reveal the spirits' presence;[292] the stone spirits are also thought to manifest in blue sparks and lights.[293] When the lights are turned on, the yuwípi wičháša will appear freed from his bonds, claiming that the spirits untied them.[294] A pipe may then be smoked by the attendees.[295] The yuwípi wičháša will dismantle the altar and ceremonial area,[296] after which a feast may be held.[297]

Scholar of religion Paul B. Steinmetz suggested that the yuwípi became the most common traditional rite among the Lakota during the reservation period due to an absence of alternatives.[298] Around the 1960s, yuwípi were the most popular traditional religious ceremonies on the Pine Ridge and Rosebud reservations,[274] although the number of yuwípi wičháša had declined substantially by the 1990s.[299] As well as seeking to treat sickness,[279] the yuwípi wičháša may also be invited to supervise the sun dance.[278] There is often much competitiveness between yuwípi wičháša as they seek to build their own client bases.[278] If a yuwípi wičháša is exposed for fraudulently producing phenomena, they may leave their reservation in disgrace.[300] It is believed that the power of the yuwípi wičháša usually decreases over time as they give away their spirits.[301] When one of them dies, their ritual paraphernalia is usually buried with them or burned.[277]

Other specialists

Certain other ritual healers have ceremonies different from the yuwípi,[302] although several of these declined under state suppression in the reservation era.[251] These groups brought together individuals deemed to have had similar visions;[303] Powers referred to them as "dream cults".[303]

Once found in Lakota religion was the mathó waphíye or bear doctor,[304] a specialist in treating wounds.[305] The bear ritual entails possession by the spirit of the bear, at which the possessed individual behaves like a bear.[306] This will also involve wearing the skin and head of a bear while carrying out healing procedures;[305] any medicinal roots they required were dug up with a bear claw.[305] Bear doctors were formerly found throughout indigenous Plains and Woodland communities and among the Lakota were probably common prior to the move to the reservations.[305] The last known bear doctor active on Pine Ridge died in 1965;[251] Feraca suggested that at the start of the 21st century none remained among the Lakota.[305]

Eagle doctors were assisted by their contact with eagle spirits.[302] The Heĥaka ihanblapi ("they dream of elks") were a sodality who dressed as elks during their ceremonies and were thought to have powers over women.[303] The Sinte sapela ("black tails") were similar, but were devoted to black tailed deer rather than elks.[121] The Mato ihanplapi ("they dream of bears") dressed as bears during their ceremonies, while the Tatang ihablapi ("they dream of buffalo bulls") dressed as buffalo.[121] The Šunkmahetu ihanblapi were inspired by wolves and prepared war medicine for protecting Lakota warriors from their enemies.[121]

The heyókha (clowns) are deemed to have the power to undo the work of other holy men.[307] Individuals join this group after experiencing dreams or visions of the wakinyan spirits,[303] who are then regarded as their friends.[308] They behave in ways contrary to custom, for instance by walking backwards,[307] or dressing warmly in summer and wearing little in winter.[303] They are often deemed amusing although also thought capable of bringing catastrophe.[307] A major heyókha ceremony is the heyókha kaga ("clown making ceremony"), involving a dance around a pot of boiling dog meat.[303] Heyókha are expected to participate in the Omaha (grass) dances;[307] although historically sometimes forbidden from the sun dance,[307] they have appeared at 21st-century sun dances, where their function was to test the commitment of the dancers by taunting them.[309]

History

Prehistory

The prehistory of Sioux-speaking peoples "is at best conjectural".[311] It is possible that the different Sioux communities originated as a single group,[312] and this common origin may be reflected in certain underlying religious ideas shared across contemporary Sioux communities.[313] Various developments in Sioux religion prior to the 19th century can be suggested.[314] Feraca noted that what archaeologists term the Prairie and Woodland cultures "still have bearing" on Lakota religion.[315] The Hopewell tradition Mound Builders of the Ohio Valley, for instance, utilised elaborate pipes, suggesting a lengthy heritage to the Lakota belief in the Sacred Pipe.[310]

The Sioux-speaking peoples first encountered Europeans in the mid-17th century.[316] At that time, the ancestors of the Lakota were members of a broad confederation that called itself the Oceti Šakowin, usually translated as the Seven Council Fires.[317] By the start of the 16th century, they were living on the headwaters of the River Mississippi.[318] From 1640, Europeans referred to the Oceti Šakowin as the Sioux, a term borrowed from the Ojibwe, in whose language it was a pejorative word meaning "lesser, or small, adder."[319] The Oceti Šakowin spoke three mutually intelligible dialects of what came to be called the Sioux language: Dakota, Nakota, and Lakota.[319] Over time, these linguistic demarcations also came to define political units.[319] Linguistic reconstruction places the homeland of the Lakota's ancestors, the proto-Western Siouans, to the west of Lake Michigan, an area encompassing southern Wisconsin, southeast Minnesota, northeast Iowa, and northern Illinois.[320]

Encounters with Christianity and colonialism

Christian contact with the Sioux-speaking peoples began circa 1665 when the Jesuit missionaries Claude Allouez and Jacques Marquette met with Dakota groups, an event followed by sporadic Roman Catholic missionary visits to the Sioux throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.[321] In the 18th century, the Lakota were among the Sioux-speaking peoples who began to migrate west,[322] a process encouraged by conflict with the Ojibwe and Cree.[323] After 1750 they entered the Black Hills area.[324] By the early 19th century, the Lakota had adopted the use of the horse, providing greater mobility and wealth and generating radical transformations of their culture.[325]

Sioux-speaking peoples first encountered official representatives of the United States government in the early 19th century.[326] By the mid-19th century, the U.S. government's approach to Native Americans was to encourage them onto reservations.[327] The Sioux Treaty of 1868 resulted in many Lakota moving onto the Great Sioux Reservation.[328] In 1876, the US Department of War ordered all Lakota to remain confined to this reservation;[329] some Lakota, such as groups led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, resisted.[330] In 1876, the US government took the Black Hills from the Lakotas and Yanktonias.[331] This loss of the Black Hills became a recurring theme in Lakota religion,[332] with many Lakotas subsequently maintaining that their people originated from the Black Hills.[23] In 1878, new agencies were set up within the Great Sioux Reservation; the Pine Ridge Agency was for the Oglalás, the Rosebud Agency was for the Sičhą́ǧus. Pine Ridge and Rosebud became separate reservations in 1889.[332]

Establishing the reservations assisted Christian proselytization among the Lakotas,[332] although Christian conversion did not always mean the rejection of traditional practices.[17] Various Christian groups were active in missionizing to the Lakota; Roman Catholic Jesuits were present by the 1880s,[333] while the Mormons established a presence on the reservations in the 20th century.[334] In tandem with the Christianisation process was the state suppression of traditional ceremonies. In 1883, a Bureau of Indian Affairs edict banned the Lakotas' practice of the sun dance and traditional funeral practices.[335] Perhaps because they were aware of the imminent ban, the 1881 sun dance ceremony at Pine Ridge featured over 40 dancers, more than usual.[229] Despite the 1883 ban, there are accounts of sun dances later taking place in secret.[336]

The Lakota also absorbed religious influences from other Native groups. Having originated among the Paiute in 1889, the Ghost Dance movement spread throughout the Great Plains and by 1890 had attracted growing popularity among Lakota.[337] U.S. authorities sought to suppress the Ghost Dance, and when trying to arrest its leaders among the Lakota they killed Sitting Bull.[338] Tensions intensified and led to the Massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890,[339] an event with a profound psychological impact on the Lakota.[340] In the 1900s, the peyote religion of the Native American Church spread into the Lakota reservations by members of the Ho-Chunk and Omaha people.[341] The Lakotas were among the last to embrace peyotism,[342] with some participating in both peyotism and traditional Lakota ceremonies.[343]

Extensive records of Lakota religion were made in the 19th century, both by non-Native collectors like James R. Walker as well as by Lakotas such as George Bushotter, George Sword, Thomas Tyon, and Ivan Stars who wrote in their own language.[344] No other Native Plains community saw their religious traditions recorded to such an extent.[344] Further records were made in the early 20th century, primarily by Black Elk, an Oglála holy man who dictated his beliefs to both John G. Neihardt and Joseph Epes Brown;[345] these were first published as Black Elk Speaks in 1932.[346] As well as having been involved in the Ghost Dance,[347] Black Elk was committed to both traditional religion and to Catholicism,[348] and taught that God had intended the Lakota's traditional religion to prepare them for the arrival of the Gospel.[349]

Revivalism

In 1934, John Collier, head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, issued a circular ending the Bureau's objections to traditional Native American religions, allowing for a revival of many Lakota traditional practices.[350] Revived sun dances occurred from at least 1924,[351] with the first major example taking place in 1934, coming to be known as "the First Annual Sun Dance."[229] The "locus for contemporary religious revitalization" came from the Lakota communities of South Dakota, especially those on the reservations at Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Cheyenne River, and Standing Rock.[352] Ritual leaders from these reservations subsequently stimulated revivals among other Sioux-speaking communities in North Dakota, Nebraska, Minnesota, Montana, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan.[352]

The 1960s and 1970s saw a revitalisation of Lakota religion.[353] From the 1960s, Christian leaders on Lakota reservations became more open to including traditional Lakota elements in their worship.[168] Following the Second Vatican Council, Roman Catholic missionaries for instance increasingly interpreted traditional religion through the lens of fulfilment theology, the notion that Christianity fulfilled ideas foreshadowed in earlier traditions. Thus, they interpreted the Sacred Pipe as a foreshadowing of Jesus Christ, linked White Buffalo Woman with the Virgin Mary, and associated the sun dance tree with the Cross of the Crucifixion.[354] In 1971 Black Elk Speaks was republished and became a bestseller, making a significant contribution to the reclamation of Lakota religion.[355] In 1978, the U.S. government passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, ensuring religious freedom to groups like the Lakota.[356]

The embrace of Lakota traditional religion was helped, as Feraca observed, by "an atmosphere of New Nativism".[357] The New Nativist movement influenced various Lakota practices; it has been attributed as the reason behind medicine men conducting weddings, something that only developed in the 1960s.[174] In 1968, several Ojibwe Natives founded the American Indian Movement (AIM) activist group.[358] AIM soon gained a Lakota focus as its members sought the guidance of Lakota religious leader Leonard Crow Dog.[359] With the support of Lakota elders, in 1973 AIM members occupied Wounded Knee. They were besieged by U.S. federal authorities and several occupiers were killed.[360] AIM politicised Lakota religion, transforming it into a symbol of resistance as part of an anti-colonial ideology;[361] they for instance converted the Lakota's sacred pipe into a Pan-Indian symbol.[362] AIM also assisted in promoting Lakota ceremonies to other Native American groups.[363] By the early 21st century, for instance, the sweat lodge ceremony had spread to indigenous communities across North America.[364]

During the 20th century some Lakota, such as Fools Crow, encouraged a universalisation of Lakota spirituality.[364] Elements of Lakota religion that proved particularly attractive to non-Lakota included the vision quest, sweat lodge, the idea of the "medicine wheel," as well as Lakota uses of the pipe, drum, and specific Plains herbs like sage and sweetgrass.[365] Various Lakota began to accuse non-Natives who adopted these practices of cultural appropriation, an accusation they did not typically also level at Native Americans of other groups.[365] In 1993, 500 representatives of the Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota Nations ratified a Declaration of War against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality, a document written by Lakota activists from Pine Ridge.[366] In 2003, Arvol Looking Horse, the Keeper of the Sacred Pipe, issued a proclamation prohibiting non-Native entry to the hocoka spaces during the seven sacred rites.[367] Certain other Lakota, such as Leonard Crow Dog, spoke against Looking Horse's proclamation, and the Afraid of Bear/American Horse Sun Dance in the Black Hills announced that it would not impose ethnic restrictions on involvement, seeing such an attitude as contrary to the spirit of mitakuye oyasin.[368]

Demographics

A study conducted on the Pine Ridge Reservation during the 2000s found that 29% of respondents described themselves as followers of Lakota religion exclusively, 28% said that they combined Lakota religion with Christianity, and 41% stated that they only followed Christianity.[369] A majority of those who considered themselves fully or three-quarters Lakota identified with Lakota religion, while those who identified as a quarter or less Lakota were more likely to identify as Christian.[370]

Reception and influence

Christian fundamentalists active among Sioux communities have typically actively opposed traditional religious expression and sought to transcend differences between indigenous and non-indigenous communities.[17] Christian missionaries tried to adapt traditional Lakota beliefs to assist conversion. They for instance sought to use the term Wakʽą Tʽąką to describe their God and the term wakan sica for demons.[371]

Various Native critics have spoken against those promoting Native-derived practices to non-Native audiences, with Sun Bear and Lynn Andrews being particularly targeted for criticism.[372] These critics are often unhappy with people commodifying Native practices for their personal enrichment while indigenous communities continue to struggle both economically and culturally.[373] Lakota and other Native American voices objecting to the non-Native uses of Lakota-derived practices have centred on four points. The first is that Native practices are being sold indiscriminately to anyone who can pay; the second is that non-Native practitioners may present themselves as an expert after taking only a workshop or course. The third is that non-Natives remove these ceremonies from their original context, and the fourth is that these practices are often blended with other, non-Native elements and worldviews.[374]

References

Citations

- Bucko 1999, p. 16.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 1.

- Feraca 2001, pp. 1–2; Posthumus 2018, p. 1.

- Feraca 2001, pp. 1–2.

- Powers 1984, pp. 26–27; Feraca 2001, p. 2.

- Stoeber 2020, p. 606.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 7.

- Owen 2008, pp. 3, 80.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 34; Steinmetz 1998, p. 50; Owen 2008, pp. 80, 178; Posthumus 2018, p. 9.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 9.

- Looking Horse 1987, p. 67.

- Grant 2017, pp. 82–83.

- Markowitz 2012, p. 12.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 273; Feraca 2001, p. 31.

- Bucko 1999, p. 15; Feraca 2001, p. 42; Crawford 2007, p. 94; Harvey 2013, p. 133.

- Bucko 1999, p. 15.

- DeMallie & Parks 1987, p. 13.

- Feraca 2001, p. 81.

- Crawford 2007, p. 17.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 6.

- Powers 1982, p. xvi.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 43; Bucko 1999, pp. 12–13; Crawford 2007, p. 91; Posthumus 2018, p. 4.

- Feraca 2001, p. 2.

- Bucko 1999, p. 14.

- Posthumus 2018, pp. 4–5.

- Hultkrantz 1980, p. 9; Owen 2008, p. 164.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 27.

- Powers 1982, p. xv; Owen 2008, p. 10.

- Powers 1982, p. xv.

- Owen 2008, p. 17.

- Owen 2008, p. 7; Posthumus 2018, p. 4.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 4.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 36.

- Crawford 2007, p. 44; Posthumus 2018, p. 36.

- DeMallie & Parks 1987, p. 8; Steinmetz 1998, p. 42.

- DeMallie & Parks 1987, p. 8; Posthumus 2018, p. 36.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 28.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 42.

- Crawford 2007, p. 44.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 28; Posthumus 2018, p. 36.

- Powers 1982, p. 47.

- Hultkrantz 1980, p. 11; Powers 1982, pp. 46–47.

- Thomas 2017, p. 452.

- Powers 1982, pp. 51–52.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 31.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 32.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 37.

- Feraca 2001, p. xii.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 28; Crawford 2007, p. 44.

- Hultkrantz 1980, p. 45; Medicine 1987, p. 166; Posthumus 2018, p. 36.

- Hultkrantz 1980, p. 45.

- Powers 1982, p. 45; Steinmetz 1998, p. 40.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 274; Feraca 2001, pp. 2–3.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 40.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 29.

- Powers 1982, p. 53.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 28; Markowitz 2012, p. 5.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 41.

- Powers 1982, pp. 47, 53.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 85.

- Powers 1982, p. 53; DeMallie 1987, p. 29.

- Feraca 2001, p. 33; Posthumus 2018, pp. 49, 78–79.

- Powers 1982, p. 54.

- Powers 1982, p. 55.

- Powers 1984, p. 43.

- Powers 1984, pp. 43–44.

- Powers 1984, p. 84.

- Crawford 2007, p. 41.

- Amiotte 1987, p. 78.

- Jahner 1987, p. 48; Crawford 2007, p. 41.

- Crawford 2007, p. 42.

- Looking Horse 1987, p. 68; Steinmetz 1998, p. 54; Crawford 2007, p. 43.

- Modaff 2016, p. 17.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 63.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 64.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 65.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 66.

- Powers 1982, p. 51.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 275.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 276.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 43; Posthumus 2018, p. 35.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 15.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 93.

- Posthumus 2018, pp. 93–94.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 94.

- Powers 1982, p. 52.

- Crawford 2007, p. 46.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 76.

- Feraca 2001, p. 56; Posthumus 2018, p. 76.

- Powers 1984, p. 11.

- Powers 1984, pp. 12–13.

- Feraca 2001, p. 56.

- Powers 1984, p. 12.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 77.

- Crawford 2007, p. 44; Posthumus 2018, p. 35.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 14.

- Medicine 1987, p. 160; Crawford 2007, p. 44; Posthumus 2018, p. 14.

- Owen 2008, p. 52; Hallowell 2010, p. 88; Posthumus 2018, p. 41.

- Feraca 2001, p. 6.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 44.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 56.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 55.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 57.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 43.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 42.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 51.

- Crawford 2007, p. 47.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 262.

- Pickering & Jewell 2008, p. 139.

- DeMallie & Parks 1987, p. 4.

- Hultkrantz 1980, p. 28.

- Owen 2008, p. 53.

- Owen 2008, p. 52.

- Medicine 1987, p. 162.

- Pickering & Jewell 2008, p. 136.

- Feraca 2001, p. 57.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 34.

- Medicine 1987, p. 161.

- Powers 1984, p. 39.

- Powers 1982, p. 64.

- Powers 1982, p. 58.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 33.

- Owen 2008, p. 5.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 43; Steinmetz 1998, p. 65.

- Feraca 2001, p. 20.

- Owen 2008, pp. 82–83.

- Owen 2008, p. 84.

- Owen 2008, p. 58.

- Medicine 1987, p. 163.

- Medicine 1987, p. 168.

- Powers 1984, p. 53.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 54; Owen 2008, pp. 48–49; Modaff 2016, p. 14.

- Owen 2008, p. 50.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 31; Posthumus 2018, p. 49.

- Feraca 2001, p. 76; Posthumus 2018, p. 85.

- Powers 1982, p. 46; Feraca 2001, p. 76.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 86.

- Powers 1984, p. 14.

- Powers 1984, p. 25.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 30.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 81.

- Powers 1982, p. 50; Powers 1984, p. 14.

- Feraca 2001, p. 77.

- Powers 1982, p. 50.

- Powers 1984, p. 15; Feraca 2001, p. 15.

- Feraca 2001, p. 15.

- Powers 1984, p. 15.

- Feraca 2001, pp. 15, 17.

- Powers 1984, p. 14; Feraca 2001, p. 36.

- Feraca 2001, p. 44.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 35.

- Powers 1984, p. 44.

- Harvey 2013, p. 133.

- Crawford 2007, p. 45.

- Powers 1984, p. 43; Crawford 2007, p. 23.

- Owen 2008, p. 83.

- Powers 1984, p. 70.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 65.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 267; Powers 1984, p. 70; Amiotte 1987, p. 85; Feraca 2001, p. 41.

- Powers 1984, pp. 62–63, 70.

- Powers 1984, p. 71.

- Grant 2017, p. 66.

- Powers 1984, p. 15; Grant 2017, p. 66.

- Posthumus 2018, pp. 55, 86.

- Grant 2017, p. 68.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 31; Thomas 2017, p. 456; Posthumus 2018, p. 55.

- Owen 2008, p. 49.

- Crawford 2007, p. 94.

- Owen 2008, p. 108.

- Powers 1984, p. 46.

- DeMallie & Parks 1987, p. 3; Feraca 2001, p. 47; Crawford 2007, p. 46.

- DeMallie & Parks 1987, p. 3.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 31; Looking Horse 1987, p. 68; Feraca 2001, p. 47; Posthumus 2018, pp. 37–38.

- Feraca 2001, p. 86.

- Feraca 2001, p. 47.

- Looking Horse 1987, p. 69.

- Looking Horse 1987, p. 69; Steinmetz 1998, p. 15; Feraca 2001, p. 91.

- Steinmetz 1998, pp. 15–16.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 33; Feraca 2001, p. 32.

- Feraca 2001, p. 32.

- Bucko 1999, p. 4; Feraca 2001, p. 32.

- Powers 1984, pp. ix–x; Steinmetz 1998, p. 58; Feraca 2001, p. 32.

- Powers 1984, p. 24.

- Powers 1984, p. 14; Feraca 2001, p. 33.

- Powers 1984, p. 26; Feraca 2001, p. 32.

- Bucko 1999, p. 1.

- Bucko 1999, p. 12.

- Bucko 1999, p. 3.

- Powers 1984, pp. 26–28; Bucko 1999, pp. 3, 6; Feraca 2001, p. 33.

- Feraca 2001, p. 34.

- Bucko 1999, p. 4.

- Bucko 1999, p. 8.

- Powers 1984, p. 26; Feraca 2001, p. 33; Crawford 2007, p. 45.

- Bucko 1999, pp. 3–4; Feraca 2001, pp. 33, 34; Crawford 2007, p. 45.

- Bucko 1999, p. 3; Feraca 2001, p. 34; Crawford 2007, p. 45.

- Bucko 1999, p. 11; Feraca 2001, p. 34.

- Bucko 1999, p. 11.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 35; Feraca 2001, p. 23.

- Feraca 2001, p. 29.

- Feraca 2001, p. 23.

- Feraca 2001, p. 25.

- Crawford 2007, p. 92.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 35; Feraca 2001, pp. 23–24; Crawford 2007, p. 45.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 35; Feraca 2001, p. 23; Crawford 2007, p. 45.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 35; Feraca 2001, p. 24.

- Feraca 2001, p. 24.

- Powers 1984, p. 35; DeMallie 1987, p. 35; Feraca 2001, p. 24.

- Powers 1984, p. 35; DeMallie 1987, p. 35; Feraca 2001, p. 24; Crawford 2007, p. 45.

- Feraca 2001, p. 24; Crawford 2007, p. 46.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 38.

- Feraca 2001, p. 25; Crawford 2007, p. 46.

- Feraca 2001, p. 9; Crawford 2007, p. 19.

- Feraca 2001, p. 9.

- Feraca 2001, p. 10.

- Feraca 2001, p. 3.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 27.

- Feraca 2001, pp. 13–14.

- Feraca 2001, p. 14; Crawford 2007, p. 20; Modaff 2016, p. 17.

- Feraca 2001, p. 14.

- Feraca 2001, p. 15; Crawford 2007, pp. 20–21.

- Amiotte 1987, pp. 76, 81–82; Feraca 2001, p. 15; Crawford 2007, p. 20.

- Amiotte 1987, p. 82; Feraca 2001, p. 15; Crawford 2007, p. 20.

- Crawford 2007, pp. 20–21.

- Feraca 2001, pp. 87–88.

- Amiotte 1987, p. 83; Steinmetz 1998, p. 26; Feraca 2001, p. 15.

- Crawford 2007, p. 21; Modaff 2016, p. 18.

- Amiotte 1987, p. 86; Crawford 2007, p. 21.

- Medicine 1987, p. 164.

- Feraca 2001, p. 11.

- Crawford 2007, p. 21.

- Crawford 2007, p. 19.

- Feraca 2001, p. 8.

- Crawford 2007, p. 23.

- Feraca 2001, p. 9; Crawford 2007, p. 23.

- Hallowell 2010, p. 87.

- Feraca 2001, p. 10; Crawford 2007, p. 23; Modaff 2016, pp. 19–20.

- Crawford 2007, p. 24.

- Crawford 2007, p. 25.

- Steinmetz 1998, pp. 34, 79; Modaff 2016, p. 20.

- Medicine 1987, p. 163; Steinmetz 1998, p. 34; Thomas 2017, p. 453.

- Crawford 2007, pp. 92–93.

- Crawford 2007, p. 93.

- Markowitz 2012, pp. 13–14.

- Owen 2008, p. 51.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 49.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 278; Feraca 2001, p. 78.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 264.

- Lewis 1987, p. 182; Feraca 2001, p. 78.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 263.

- Feraca 2001, p. 78.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 265.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 273.

- Powers 1982, p. 57; Feraca 2001, p. 47.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 95.

- Markowitz 2012, p. 7.

- Feraca 2001, pp. 89, 91.

- Feraca 2001, p. 45.

- Powers 1982, p. 57; Feraca 2001, p. 43.

- Feraca 2001, p. 90.

- Feraca 2001, p. 46.

- Powers 1982, pp. 61–62; Feraca 2001, p. 24.

- Powers 1982, p. 62; Feraca 2001, p. 25.

- Feraca 2001, p. 26.

- Feraca 2001, p. 27.

- Feraca 2001, p. 43.

- Powers 1982, p. 63; Feraca 2001, p. 27.

- Powers 1982, pp. 52, 63; Feraca 2001, p. 27.

- Powers 1982, pp. 52–53.

- Powers 1982, p. 63.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 264, 266; Feraca 2001, p. 31.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 266.

- Lewis 1987, p. 185.

- Powers 1984, p. 88; Feraca 2001, p. 30.

- Feraca 2001, p. 30.

- Kemnitzer 1976, pp. 270–271.

- Feraca 2001, pp. 30, 46.

- Powers 1984, p. 19.

- Powers 1984, p. 21.

- Powers 1984, p. 20.

- Powers 1984, p. 40.

- Powers 1984, pp. 11–12; Feraca 2001, p. 56.

- Hurt 1960, p. 49; Powers 1984, p. x; Feraca 2001, p. 35.

- Hurt 1960, p. 49; Kemnitzer 1976, p. 267; Powers 1984, pp. 41–42; Feraca 2001, pp. 35–38.

- Feraca 2001, p. 39.

- Hurt 1960, p. 49; Kemnitzer 1976, p. 269.

- Powers 1984, pp. 54–56; Lewis 1987, p. 180; Feraca 2001, p. 39.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 66.

- Hurt 1960, p. 49; Kemnitzer 1976, p. 269; Powers 1984, p. 54; Lewis 1987, p. 180; Feraca 2001, p. 39.

- Feraca 2001, pp. 30–31.

- Hurt 1960, p. 51; Powers 1984, pp. 56–58; Feraca 2001, p. 40.

- Powers 1984, p. 64.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 269.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 78.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 270; Powers 1984, p. 66; Feraca 2001, p. 41.

- Kemnitzer 1976, p. 270; Powers 1984, pp. 66–67.

- Hurt 1960, p. 51; Kemnitzer 1976, p. 270; Powers 1984, p. 67; Feraca 2001, p. 41.

- Hurt 1960, p. 51; Kemnitzer 1976, p. 270; Lewis 1987, p. 182; Powers 1984, p. 69; Feraca 2001, p. 42.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 18.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 18; Feraca 2001, p. 90.

- Feraca 2001, p. 82.

- Powers 1984, p. 42.

- Feraca 2001, pp. 53–54.

- Powers 1982, p. 57.

- Feraca 2001, p. 28.

- Feraca 2001, p. 53.

- DeMallie 1987, p. 41.

- Feraca 2001, p. 50.

- Modaff 2016, p. 21.

- Modaff 2016, pp. 21–22, 24.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 15.

- Powers 1982, p. 16.

- Powers 1982, p. 15.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 5.

- DeMallie & Parks 1987, p. 8.

- Feraca 2001, p. 1.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 7.

- Powers 1982, p. 3.

- Powers 1982, p. 116.

- Powers 1982, p. 5.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 6.

- DeMallie & Parks 1987, p. 9.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 3; Feraca 2001, p. 1; Posthumus 2018, p. 8.

- Powers 1982, p. 17; Steinmetz 1998, p. 3.

- Steinmetz 1998, p. 3.

- Posthumus 2018, p. 8.

- Powers 1982, pp. 17–18.

- Crawford 2007, p. 80.

- Feraca 2001, p. 3; Crawford 2007, p. 71.

- Crawford 2007, p. 72.

- Feraca 2001, p. 3; Crawford 2007, p. 72.

- Feraca 2001, pp. 3–4.