Lâm Văn Phát

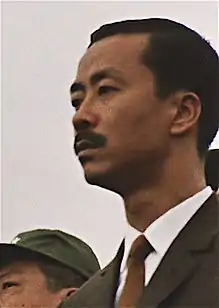

Major General Lâm Văn Phát (1920 – 30 October 1998) was a Vietnamese army officer. He is best known for leading two coup attempts against General Nguyễn Khánh in September 1964 and February 1965. Although both failed to result in his taking power, the latter caused enough instability that it forced Khánh to resign and go into exile.

Lâm Văn Phát | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1920 Cần Thơ, French Indochina |

| Died | 30 October 1998 (aged 77–78) California, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 19??–1965 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | 2nd Division (June 1961 – June 1963) 7th Division (December 1963 – February 1964) III Corps (February 1964 – September 1964) |

| Battles/wars | |

| Other work | Interior Minister (removed September 1964) |

A member of the Roman Catholic minority, Phát joined the French-backed Vietnamese National Army which became the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) after the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) was established. After having been sent to the U.S. for further training in 1958, Phát returned home to head the Civil Guard, a paramilitary force then mostly used to protect the ruling family of President Ngô Đình Diệm, rather than to counteract the communist Việt Cộng insurgency. Later commanding the 2nd Division, he was known for his loyalty to Diệm, who favored fellow Catholics. In 1963, Diệm knew some of the generals were about to launch a coup against him. He appointed Phát to command the 7th Division, located near the capital, Saigon, so he could help in the fighting, but the plotters successfully used delaying tactics so that the paperwork for the transfer of the division leadership could not occur before they proceeded to overthrow and execute Diệm. Despite Phát's pro-Diệm allegiance he was promoted to brigadier general and given command of the 7th Division.

After the January 1964 coup against Dương Văn Minh, Phát was made the commander of III Corps and also Interior Minister for a time until he was dismissed in September 1964. This prompted him to join Dương Văn Đức, another general relieved of command, in launching a coup attempt against Khánh on 13 September. They initially took over the capital without a fight, but Khánh escaped, and after having received endorsements from the U.S., defeated Phát and Đức. At the military trial that followed, charges were dropped. In February 1965, Phát joined with fellow Catholic, Diệm protégé and Khánh opponent Phạm Ngọc Thảo – actually a communist agent intent on maximizing infighting in South Vietnam – in another coup attempt. After the forces deadlocked, Phát met with Republic of Vietnam Air Force chief Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, insisting on Khánh's assassination. After the meeting concluded, the coup collapsed, but Khánh was forced from office the next day. Phát and Thảo went into hiding and were sentenced to death in absentia by Kỳ's military tribunal. Thảo was killed under mysterious circumstances, but Phát evaded capture for three years until surrendering. By this time Kỳ's power had been eclipsed by another Catholic, General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, who freed Phát from prison.

Early military career

The President of South Vietnam, Ngô Đình Diệm, heavily favored Catholics, and, as a result, Phát rose quickly up the ranks. Having started his career in the French-backed Vietnamese National Army of the State of Vietnam, Phát became a member of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam after the State of Vietnam became the Republic of Vietnam. In 1958, holding the rank of colonel, Phát was sent to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas for officer training.[1] Described as being tall for relatively short Vietnamese norms, Phát "spoke halting English".[1] After returning to Vietnam, he served as the head of the Civil Guard,[1] a paramilitary force that was mostly used at the time to protect the ruling family of President Ngô Đình Diệm rather than to counteract the communist Viet Cong insurgency.

Phát has been described as a "political Catholic",[1] a term for those who practiced or converted to the religion to curry favor with Diệm, who made most military and political appointments and promotions on the basis of religion.[2] Phát's habit of customarily being seen in public with a swagger stick and his reputation for autocratic leadership alienated most of his subordinate officers.[1] He grew his pinky fingernail to great length, a practice observed by mandarins during Vietnam's imperial era to denote their status. Some observers claimed that the mandarin style of his fingernail spread to his general behavior, decrying him as "haughty" and "hawklike".[1] U.S. military advisors regarded Phát as "mediocre".[3] As a colonel, he served as the commander of 2nd Division, located in central Vietnam from 8 June 1961 until 18 June 1963, when he was replaced by Colonel Trương Văn Chương.[4]

Overthrow of Diệm in 1963

By late 1963, Diệm knew a coup was brewing and that the 7th Division at Mỹ Tho outside Saigon might be involved. As it was close to the capital, it would play a crucial role in either attacking or defending Diệm, or blocking outlying units from entering the city. Diệm put Phát in command of the 7th Division on 31 October.[5] According to tradition, Phát had to pay the corps commander a courtesy visit before assuming control of the division. However, General Tôn Thất Đính, commander of the III Corps was part of the plot and deliberately refused to see Phát and told him to come back at 14:00 the following day, by which time the coup had already been scheduled to start. In the meantime, Đính had General Trần Văn Đôn sign a counter-order transferring command of the 7th Division to his deputy and co-conspirator Nguyễn Hữu Có.[5]

Có then trapped and arrested the 7th Division's officers on the day of the coup.[5][6] He then phoned General Huỳnh Văn Cao, further south in the Mekong Delta's largest town, Cần Thơ, where the IV Corps was headquartered. Có, a central Vietnamese, imitated Phát's southern accent and tricked Cao into thinking that nothing unusual was happening.[5] Phát's removal had thus stopped Cao from sending loyalists to Saigon to save Diệm,[7] who was captured and executed the following day.[8] Despite the fact that Đính saw Có as being more reliable for the purposes of staging the coup against Diệm, Minh promoted him to brigadier general immediately after the officers seized power.[1] As a brigadier general, he served as the commander of the 7th Division, from 2 December 1963 until 2 February 1964.[4]

Nguyễn Khánh

He was then promoted and served as the commander of III Corps, which oversaw the region of the country surrounding Saigon from 2 February until 4 April 1964, when he was replaced by Lieutenant General Tran Ngoc Tam.[4] Phát's promotion coincided with a coup by General Nguyễn Khánh against the officers who removed Diệm. Many of these, such as Generals Trần Văn Đôn, Lê Văn Kim, Tôn Thất Đính and Mai Hữu Xuân were put under house arrest, opening up vacancies for other generals.[9][10]

Phát was regarded as a dour military tactician who persisted with his pre-devised battleplan once hostilities had commenced, refusing to change tactics even when difficulties arose. In one engagement in 1964 in Bến Tre Province in the Mekong Delta, Phát was blamed for the loss of an American helicopter in addition to heavy personnel losses after he proceeded with an attack despite advice to the contrary from his junior officers. U.S. military advisers who worked with Phát reportedly regarded him as competent, albeit dour and lacking in charisma.[1]

September 1964 coup attempt

In September 1964, Phát was dismissed as Interior Minister, while General Dương Văn Đức was about to be removed as IV Corps commander.[11] Both were removed partly due to pressure from Buddhist activists, who accused Khánh of accommodating too many Catholic pro-Diệm elements in leadership positions.[12] This came after Khánh attempted to augment his power in August by declaring a state of emergency and introducing a new constitution, which resulted in mass unrest and calls for civilian rule, forcing Khánh to make concessions in an attempt to dampen discontent.[13] Disgruntled, the pair tried to launch a coup attempt of their own in the pre-dawn hours of 13 September, using 10 army battalions they had recruited.[14] They gained the support of Colonel Lý Tòng Bá, head of the 7th Division's armored section.[3] The coup was supported by Catholic and Đại Việt elements.[15] Another member of the conspiracy was Colonel Phạm Ngọc Thảo, who, while ostensibly a Catholic, was actually a communist double agent trying to maximize infighting at every possible opportunity.[16][17] General Trần Thiện Khiêm, a member of the ruling triumvirate along with Khánh and Minh, but a rival of the dominant Khánh, was also believed to have supported the plot.[16]

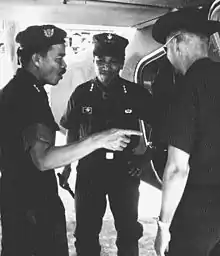

Four battalions of rebel troops moved before dawn towards Saigon from the Mekong Delta, with armored personnel carriers and jeeps carrying machine guns. After cowing a police checkpoint on the edge of the capital, they put sentries in their place to seal off Saigon from incoming or outgoing traffic. They then captured communication facilities in the capital. As the rebel troops took over the city without any firing and sealed it off, Phát sat in a civilian vehicle and calmly said, "We'll be holding a press conference in town this afternoon at 4 pm"[3][18] Claiming to represent The Council for the Liberation of the Nation, Phát proclaimed the deposal of Khánh's "junta" over national radio, and accused Khánh of promoting conflict within the nation's military and political leadership. He promised to capture Khánh and pursue a policy of increased anti-communism,[19] stronger government and military.[20] Phát stated he would return to the crypto-fascist, Catholic integrist ideology of the Ngô family to lay the foundation for his junta.[12] According to historian George McTurnan Kahin, Phát's broadcast was "triumphant" and may have prompted senior officers who were neither part of the original conspiracy nor fully loyal to Khánh to conclude that Phát and Đức would not embrace them if they rallied to their side.[21]

There was little reaction from most of the military commanders.[12] Phát's rebels set up their command post in the Saigon home of General Dương Ngọc Lắm, a Diệm loyalist who had been removed from his post as Mayor of Saigon by Khánh.[9][19] In contrast to Phát's serene demeanour, his incoming troops prompted worshippers at the Roman Catholic cathedral attending mass to flee in panic. The Buddhists, however, made no overt reaction to a coup that would dent their rights. Air Force commander Kỳ had promised two weeks earlier to use his planes against any coup attempt, but there was no reaction early in the morning. Đức mistakenly thought Kỳ and his subordinates would join the coup, but later realized that he was mistaken. After he found out that he had been tricked into thinking that the plotters had great strength, he defected.[22] Several U.S. advisers were chased away by rebel officers who did not want interference in the coup. They thought the Americans would not approve of their actions, as both U.S. Ambassador Maxwell Taylor and President Lyndon Johnson had made optimistic comments about South Vietnam recently.[3]

Phát and Đức failed to apprehend Khánh, who had escaped the capital and flew to the central highlands resort town of Đà Lạt.[12] Their forces stormed Khánh's office and arrested his duty officers but could not find him.[3] There was then a lull in the power struggle. One Vietnamese official said that "All these preparations are the result of a big misunderstanding on both sides. I don't think either group will start anything, but both think the other will."[3]

American officials followed Khánh to encourage him to return to Saigon and reassert his control. The general refused to do so unless the Americans publicly announced their support for him to the nation. They then asked Khánh about his plans for the future, but felt that he was directionless. After talking to Phát and Đức, they concluded the same and decided to back the incumbent and publicly released a statement through the embassy to endorse Khánh.[12] The announcement helped to deter ARVN officers from joining Phát and Đức, who decided to give up, the former only temporarily, however.[11]

Kỳ then decided to make a show of force and sent jets to fly low over Saigon and finish off the rebel stand.[3] He also sent two C-47s to Vũng Tàu to pick up two companies of South Vietnamese marines who remained loyal to Khánh. Several more battalions of loyal infantry were transported into Saigon.[3] Phát withdrew with his forces to the Mỹ Tho base of the 7th Division.[23] In the early hours of 14 September, before dawn, Kỳ met senior coup leaders at Tân Sơn Nhất and told them to back down, which they did.[18]

After the coup collapsed, Kỳ held a press conference claiming that the senior officers involved in the stand-off "have agreed to rejoin their units to fight the Communists", naming Phát among them.[18] Kỳ claimed no further action would be taken against those involved with Phát and Đức's activities,[23] and that events in the capital were being misinterpreted by observers, as "there was no coup".[18] Despite the media event, Phát and Colonel Huỳnh Văn Tôn remained defiant after returning to the latter's 7th Division's headquarters in Mỹ Tho. Tôn was threatening to break away from the government.[24] On 16 September, Khánh had the plotters arrested; Phát returned to Saigon to turn himself in, the last to be taken into custody.[23] Three of the four corps commanders and six of the nine division commanders were removed for failing to move against Phát and Đức.[11]

Kỳ's role in putting down Phát and Đức's coup attempt gave him more leverage in Saigon's military politics. Indebted to Kỳ and his supporters for maintaining his hold on power, Khánh was now in a weaker position. Kỳ's group called on Khánh to remove "corrupt, dishonest and counterrevolutionary" officers, civil servants and exploitationists, and threatened to remove him if he did not enact their proposed reforms.[22]

Phát and 19 others were put on trial in a military court; observers predicted that he would be the only one to face the death penalty. Phát's lawyers started by unsuccessfully moving for the charges against the conspirators to be dismissed, claiming the rebels had not been captured "red-handed". They were more successful in another demand, managing to persuade the five judges to allow witnesses to be called. The court agreed to their request to compel Khánh, Kỳ, and Deputy Prime Minister Nguyễn Xuân Oánh to appear before the hearing. The accused officers claimed they had only intended to make a show of force, rather than overthrow Khánh.[25] Asked why he had denounced Khánh as a "traitor" during a broadcast on national radio during the coup attempt, Phát claimed he had merely "gotten excited".[25]

Phát was asked about the collapse of his coup attempt and he discussed his visit to the American Embassy along with labor union leader Trần Quốc Bửu. Phát claimed his discussion with deputy ambassador U. Alexis Johnson was "not too important" and played down its impact, claiming that Johnson's limited usage of French had limited any talks he would have wanted to have. However, Bửu contradicted Phát, telling journalists the meeting with Johnson had lasted around 90 minutes.[25] One week later on 24 October, the charges were dropped,[26] because Khánh needed support for his fragile regime and wanted to have a counterweight against Kỳ and Thi.[21] Khánh sentenced Phát and Đức to two months of detention; their subordinates were given even shorter sentences.[26]

February 1965 coup attempt

In 1965, Phát was involved in another coup attempt against Khánh. Colonel Thảo and General Khiêm had both been sent by Khánh to Washington to keep them away from plotting. In late December 1964, Thảo was summoned back to Saigon by Khánh, who correctly thought he was plotting with Khiêm to launch another coup. Thảo, likewise, suspected Khánh was attempting to have him killed,[27][28] so he underground upon returning to Saigon,[27] and began plotting,[29] having been threatened with being charged for desertion.[27] Due to his Catholic background, Thảo was able to recruit Catholic pro-Diệm loyalists such as Phát.[30] Thảo was still successfully operating as a double agent.[17] By this stage, the Americans had fallen out with Khánh and were encouraging various Vietnamese officers to launch a coup, and the Thảo-led effort caught them out. [31]

Between January and February, Thảo began plotting his own counter-coup.[32] He consulted with Air Force Chief Kỳ and tried to convince him to join the coup, but Kỳ stated that he would remain neutral. Thảo believed Kỳ would not intervene against him.[33] Shortly before noon on 19 February, Thảo and Phát attacked, using some 50 tanks and a mixture of infantry battalions to seize control of the military headquarters, the post office and the radio station in Saigon. They surrounded Khánh's home as well as Gia Long Palace, the residence of head of state Phan Khắc Sửu.[32][34] At the same time Phát headed towards Tân Sơn Nhất to capture the country's military headquarters with an assortment of marines, paratroopers and special forces troops.[34]

At the same time, most of the senior officers had been in meetings with American officials at Tân Sơn Nhất since the early morning, and Khánh left at 12:30. The plotters had secured the cooperation of someone working inside the Joint General Staff headquarters. This collaborator was supposed to have closed the gate so that Khánh would be held up, but left them open.[35]

Some of the other senior officers in the Armed Forces Council were not so lucky, and they were caught by Phát's troops inside headquarters, while other buildings of the military complex remained under junta control.[36] Khánh managed to escape to Vũng Tàu. His plane was just emerging from the hangar and lifted off just as rebel tanks were rolling in, attempting to block the runway and shut down the airport.[33][34][37] Phát's ground troops also missed capturing Kỳ, who fled through the streets in a sports car with his wife and mother-in-law.[38] Kỳ ended up at Tân Sơn Nhất, where he ran into Khánh; the pair flew off together to regroup.[36]

Thảo made a radio announcement stating that the sole objective of his military operation was to get rid of Khánh, whom he described as a "dictator".[32] He said he intended to recall Khiêm to Saigon to lead the Armed Forces Council in place of Khánh, while his supporters made pro-Diệm speeches. It was later concluded that the coup was again mostly by hard-core Diệm loyalists and Catholics.[39] This turned American officials against the coup as they feared that the plotters would lead a divisive regime that would inflame sectarian tensions and play into the hands of the communists, so they decided to look for officers to defeat Thảo and Phát.[40]

Phát was supposed to seize the second largest air force base in the country, located in the satellite city of Biên Hòa outside Saigon. This was to prevent Kỳ from mobilizing air power against them,[30][32] but this failed, as Kỳ had already flown there to take control after dropping Khánh off at Vũng Tàu. Phát could not challenge Kỳ's fighter planes, which were already patrolling the air above Biên Hòa by the time they arrived.[36] Kỳ flew a short distance southwest and circled Tân Sơn Nhất, threatening to bomb the rebels.[32][33] Kỳ had never trusted Thảo or Phát, and did not want them in power.[41] Most of the forces of the III and IV Corps surrounding the capital disliked both Khánh and the rebels, and took no action.[42] As nightfall came, it appeared that forces loyal to Khánh were strengthening as they began to move towards Saigon.[41]

At 20:00, Thảo and Phát met Kỳ in a meeting organized by the Americans, and insisted Khánh be removed from power. The coup collapsed when, between midnight and dawn, anti-coup forces swept into the city. Whether the rebels were defeated or a deal was struck with Kỳ to end the revolt in exchange for Khánh's removal is disputed.[32][43][44] According to the latter version, Thảo and Phát agreed to free the members of the Armed Forces Council whom they had arrested and to withdraw in exchange for Khánh's complete removal from power.[41] Thảo and Phát were given an appointment with the figurehead chief of state, Sửu, who was under the close control of the junta, to "order" him to sign a decree stripping Khánh of the leadership of the military.[41] Before fleeing, Phát changed into civilian clothes and made a broadcast stating "We have capitulated", before leaving with Colonel Tôn, who had also participated in his September 1964 coup attempt.[45] The Armed Forces Council then adopted a vote of no confidence in Khánh and forced him into exile, while Kỳ assumed control.[32][46]

Post-military life

Thảo and Phát were stripped of their ranks, but nothing was initially done as far as prosecuting or sentencing them for their involvement in the coup for the time being.[47] They went into hiding in Catholic villages and offered to surrender and support the government if they and their officers were granted amnesty.[48] However, this failed to materialize, and in May 1965, a military tribunal loyal to Kỳ sentenced both to death in absentia.[49]

In July 1965, Thảo was hunted down and is believed to have been executed in unclear circumstances.[49] Phát remained on the run for three years. During that time, Kỳ's power was eclipsed by General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, a Catholic and a Diệmist, in a continuing power struggle. Thiệu became president in 1967 with Kỳ as his deputy, and over time began to work himself into a dominant position, removing his deputy's supporters in the military from positions of high power. In June 1968, Phát came out of hiding and surrendered himself to the authorities. He was pardoned by the Thiệu-dominated military court in August and released.[50] His last-known assignment was as Military Governor of Saigon from 28 to 30 April 1975, when Saigon fell, under General Dương Văn Minh.

Other

Little is known of Phát's personal life except that he was married and, according to The New York Times, believed to have been in his late 30s when he made his coup attempts, implying he was born in the mid-to-late 1920s.[1] He died in 1998.

References

- "Challenger in Saigon: Lam Van Phat". The New York Times. 14 September 1964. p. 14.

- Jacobs, pp. 85–95.

- "South Viet Nam: Continued Progress". Time. 18 September 1964.

- Tucker, pp. 526–33.

- Halberstam, David (6 November 1963). "Coup in Saigon: A Detailed Account". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- Karnow, p. 321.

- Moyar, p. 270.

- Karnow, pp. 323–26.

- Shaplen, pp. 228–40.

- Kahin, pp. 198–204.

- Karnow, p. 396.

- Moyar, p. 327.

- Moyar, pp. 315–20.

- Moyar, p. 326.

- Shaplen, p. 288.

- Kahin, p. 231.

- Karnow, pp. 39–40.

- "Coup collapses in Saigon; Khanh forces in power; U.S. pledges full support". The New York Times. 14 September 1964. p. 1.

- "Key posts taken". The New York Times. 13 September 1964. p. 1.

- Grose, Peter (14 September 1964). "Coup Lasted 24 Hours". The New York Times. p. 14.

- Kahin, p. 232.

- "South Viet Nam: Remaking a Revolution". Time. 25 September 1964.

- "Khanh arrests 5 in coup attempt". The New York Times. 17 September 1964. p. 10.

- "Dissident Said to Hold Out". The New York Times. 16 September 1964. p. 2.

- Langguth, Jack (16 October 1964). "Trial of officers starts in Saigon". The New York Times. p. 4.

- Grose, Peter (25 October 1964). "Vietnam council chooses civilian as chief of state". The New York Times. p. 1.

- Shaplen, pp. 308–09.

- Tang, pp. 56–57.

- Tang, p. 57.

- VanDeMark, p. 80.

- Kahin, pp. 295–99.

- Shaplen, pp. 310–12.

- VanDeMark, p. 81.

- Moyar, p. 363.

- Kahin, p. 514.

- Kahin, p. 300.

- Tang, p. 363.

- "South Viet Nam: A Trial for Patience". Time. 26 February 1965.

- Kahin, pp. 299–300.

- Kahin, p. 301.

- Kahin, p. 302.

- Moyar, pp. 363–64.

- Moyar, p. 364.

- VanDeMark, p. 82.

- "Dissident General Yields". The New York Times. 20 February 1965. p. 2.

- Langguth, pp. 346–47.

- Kahin, p. 303.

- Shaplen, pp. 321–22.

- Shaplen, pp. 338–44.

- "Saigon Frees General". The New York Times. 18 August 1968. p. 3.

Sources

- Jacobs, Seth (2006). Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diem and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950–1963. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-4447-8.

- Jones, Howard (2003). Death of a Generation: How the Assassinations of Diem and JFK Prolonged the Vietnam War. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505286-2.

- Kahin, George McT. (1986). Intervention: How America Became Involved in Vietnam. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-394-54367-X.

- Karnow, Stanley (1997). Vietnam: A History. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-84218-4.

- Langguth, A. J. (2000). Our Vietnam: The War, 1954–1975. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-81202-9.

- Moyar, Mark (2006). Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954–1965. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-86911-0.

- Shaplen, Robert (1966). The Lost Revolution: Vietnam 1945–1965. London: André Deutsch. OCLC 460367485.

- Truong Nhu Tang (1986). Journal of a Vietcong. London: Cape. ISBN 0-224-02819-7.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (ed.) (2000). Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social and Military History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-040-9.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - VanDeMark, Brian (1995). Into the Quagmire: Lyndon Johnson and the Escalation of the Vietnam War. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509650-9.