Landau–Kleffner syndrome

Landau–Kleffner syndrome (LKS)—also called infantile acquired aphasia, acquired epileptic aphasia[1] or aphasia with convulsive disorder—is a rare childhood neurological syndrome.

| Landau–Kleffner syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

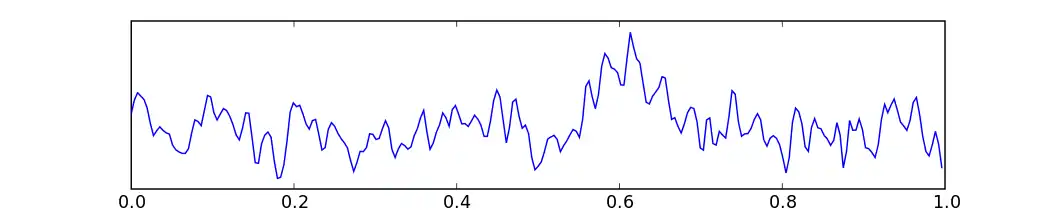

| Landau–Kleffner syndrome is characterized by aphasia and an abnormal EEG | |

| Specialty | Neurology, psychiatry |

It is named after William Landau and Frank Kleffner, who characterized it in 1957 with a diagnosis of six children.[2][3]

Signs and symptoms

The Landau–Kleffner syndrome is characterized by the sudden or gradual development of aphasia (the inability to understand or express language) and an abnormal electroencephalogram (EEG).[4] LKS affects the parts of the brain that control comprehension and speech (Broca's area and Wernicke's area). The disorder usually occurs in children between the ages of 3 and 7 years. There appears to be a male dominance in the diagnosis of the syndrome (ratio of 1.7:1, men to women).[5]

Typically, children with LKS develop normally, but then lose their language skills. While many affected individuals have clinical seizures, some only have electrographic seizures, including electrographic status epilepticus of sleep (ESES). The first indication of the language problem is usually auditory verbal agnosia. This is demonstrated in patients in multiple ways including the inability to recognize familiar noises and the impairment of the ability to lateralize or localize sound. In addition, receptive language is often critically impaired, however in some patients, impairment in expressive language is the most profound. In a study of 77 cases of Landau–Kleffner syndrome, 6 were found to have this type of aphasia. Because this syndrome appears during such a critical period of language acquisition in a child's life, speech production may be affected just as severely as language comprehension.[5] The onset of LKS is typically between 18 months and 13 years, the most predominant time of emergence being between 3 and 7 years.

Generally, earlier manifestation of the disease correlates with poorer language recovery, and with the appearance of night seizures that last for longer than 36 months.[5] LKS has a wide range of symptom differences and lacks a uniformity in diagnostic criteria between cases, and many studies don't include follow-ups on the patients, so no other relationships between symptoms and recovery have been made known.[3]

Language deterioration in patients typically occurs over a period of weeks or months. However, acute onset of the condition has also been reported as well as episodic aphasia.

Seizures, especially during the night, are a heavily weighted indicator of LKS. The prevalence of clinical seizures in acquired epileptic aphasia (LKS) is 70–85%. In one third of patients, only a single episode of a seizure was recorded. The seizures typically appear between the ages of 4 and 10 and disappear before adulthood (around the age of 15).[5]

Often, behavioral and neuropsychologic disturbances accompany the progression of LKS. Behavioral issues are seen in as many as 78% of all cases. Hyperactivity and a decreased attention span are observed in as many as 80% of patients as well as rage, aggression, and anxiety. These behavior patterns are considered secondary to the language impairment in LKS. Impaired short-term memory is a feature recorded in long-standing cases of acquired epileptic aphasia.[5]

Cause

Most cases of LKS do not have a known cause. Occasionally, the condition may be induced secondary to other diagnoses, such as low-grade brain tumors, closed-head injuries, Neurocysticercosis, and Demyelinating Disease. Central Nervous System vasculitis may be associated with this condition as well.

Diagnosis

The syndrome can be difficult to diagnose and may be misdiagnosed as autism, pervasive developmental disorder, hearing impairment, learning disability, auditory/verbal processing disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, intellectual disability, childhood schizophrenia, or emotional/behavioral problems. An EEG (electroencephalogram) test is imperative to a diagnosis. Many cases of patients exhibiting LKS will show abnormal electrical brain activity in both the right and left hemispheres of the brain; this is exhibited frequently during sleep.[3] Even though an abnormal EEG reading is common in LKS patients, a relationship has not been identified between EEG abnormalities and the presence and intensity of language problems. In many cases however, abnormalities in the EEG test has preceded language deterioration and improvement in the EEG tracing has preceded language improvement (this occurs in about half of all affected children). Many factors inhibit the reliability of the EEG data: neurologic deficits do not closely follow the maximal EEG changes in time.[5]

The most effective way of confirming LKS is by obtaining overnight sleep EEGs, including EEGs in all stages of sleep. Many conditions like demyelination and brain tumors can be ruled out by using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In LKS, fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) and positron emission tomography (PET) scanning can show decreased metabolism in one or both temporal lobes – hypermetabolism has been seen in patients with acquired epileptic aphasia.[5]

Most cases of LKS do not have a known cause. Occasionally, the condition may be induced secondary to other diagnoses such as low-grade brain tumors, closed-head injury, neurocysticercosis, and demyelinating disease. Central Nervous System vasculitis may be associated with this condition as well.[5]

Differential diagnosis

The table below demonstrates the extensive and differential diagnosis of acquired epileptic aphasia along with Cognitive and Behavioral Regression:[5]

| Diagnosis | Deterioration | EEG Patterns |

|---|---|---|

| Autistic epileptiform regression | Expressive language, RL, S, verbal and nonverbal communication | Centrotemporal spikes |

| Autistic regression | Expressive language, RL, S, verbal and nonverbal communication | Normal |

| Acquired epileptic aphasia | RL, possibly behavioral | Left or right temporal or parietal spikes, possibly ESES |

| Acquired expressive epileptic aphasia | Expressive language, oromotor apraxia | Centrotemporal spikes |

| (ESES) | Expressive language, RL, possibly behavioral | ESES |

| Developmental dysphasia (developmental expressive language disease) | No; lack of expressive language acquisition | Temporal or parietal spikes |

| Disintegrative epileptiform disorder | Expressive language, RL, S, verbal and nonverbal communication, possibly behavioral | ESES |

| Stuttering | Expressive language, no verbal-auditory agnosia | Spike-and-wave discharges on the left temporocentral and frontal regions[6] |

Note: EEG = electroencephalographic; ESES = electrical status epilepticus of sleep; RL = receptive language; S = sociability

- Continuous spike and wave of slow-wave sleep (>85% of slow-wave sleep).

Treatment

Treatment for LKS usually consists of medications, such as anticonvulsants[7] and corticosteroids[8] (such as prednisone),[9] and speech therapy, which should be started early. Some patients improve with the use of corticosteroids or adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) which lead researches to believe that inflammation and vasospasm may play a role in some cases of acquired epileptic aphasia.[5]

A controversial treatment option involves a surgical technique called multiple subpial transection[10] in which multiple incisions are made through the cortex of the affected part of the brain beneath the pia mater, severing the axonal tracts in the subjacent white matter. The cortex is sliced in parallel lines to the midtemporal gyrus and perisylvian area to attenuate the spread of the epileptiform activity without causing cortical dysfunction. There is a study by Morrell et al. in which results were reported for 14 patients with acquired epileptic aphasia who underwent multiple subpial transections. Seven of the fourteen patients recovered age-appropriate speech and no longer required speech therapy. Another 4 of the 14 displayed improvement of speech and understanding instructions given verbally, but they still required speech therapy. Eleven patients had language dysfunction for two or more years.[11] Another study by Sawhney et al. reported improvement in all three of their patients with acquired epileptic aphasia who underwent the same procedure.[12]

Various hospitals contain programs designed to treat conditions such as LKS like the Children's Hospital Boston and its Augmentative Communication Program. It is known internationally for its work with children or adults who are non-speaking or severely impaired. Typically, a care team for children with LKS consists of a neurologist, a neuropsychologist, and a speech pathologist or audiologist. Some children with behavioral problems may also need to see a child psychologist and a psychopharmacologist. Speech therapy begins immediately at the time of diagnosis along with medical treatment that may include steroids and anti-epileptic or anti-convulsant medications.

Patient education has also proved to be helpful in treating LKS. Teaching them sign language is a helpful means of communication and if the child was able to read and write before the onset of LKS, that is extremely helpful too.

Prognosis

The prognosis for children with LKS varies. Some affected children may have a permanent severe language disorder, while others may regain much of their language abilities (although it may take months or years). In some cases, remission and relapse may occur. The prognosis is improved when the onset of the disorder is after age 6 and when speech therapy is started early. Seizures generally disappear by adulthood. Short-term remissions are not uncommon in LKS but they create difficulties in evaluating a patient's response to various therapeutic modalities.

The following table demonstrate the Long-Term Follow-up of Acquired Epileptic Aphasia across many different instrumental studies:.[5]

| Study | Number of Patients | Mean Follow-up, y | Number of Patients with Normal or Mild Language Problems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soprano et al. (1994) | 12 | 8 | 3 |

| Mantovani and Landau (1980) | 9 | 22 | 6 |

| Paquier (1992) | 6 | 8.1 | 3 |

| Rossi (1999) | 11 | 9.7 | 2 |

| Robinson et al. (2001) | 18 | 5.6 | 3 |

| Duran et al. (2009) | 7 | 9.5 | 1 |

| Total | 63 | 18 (28.6%) |

Lower rates of good outcomes have been reported, ranging between 14% and 50%. Duran et al. used 7 patients in his study (all males, aged 8–27 years of age) with LKS. On long-term followup, most of his patients did not demonstrate total epilepsy remission and language problems continued. Out of the seven patients, one reported a normal quality of life while the other six reported aphasia to be a substantial struggle. The Duran et al. study is one of few that features long-term follow up reports of LKS and utilizes EEG testing, MRIs, the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, the Connor's Rating Scales-revised, and a Short-Form Health Survey to analyze its patients.[13]

Globally, more than 200 cases of acquired epileptic aphasia have been described in the literature. Between 1957 and 1980, 81 cases of acquired epileptic aphasia were reported, with 100 cases generally being diagnosed every 10 years.[5]

References

- "Landau–Kleffner syndrome" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- Landau WM, Kleffner FR (August 1957). "Syndrome of acquired aphasia with convulsive disorder in children". Neurology. 7 (8): 523–30. doi:10.1212/wnl.7.8.523. PMID 13451887. S2CID 2093377. Reproduced as Landau WM, Kleffner FR (November 1998). "Syndrome of acquired aphasia with convulsive disorder in children. 1957". Neurology. 51 (5): 1241, 8 pages following 1241. doi:10.1212/wnl.51.5.1241-a. PMID 9867583. S2CID 45332481.

- "Landau-Kleffner Syndrome (LKS or Infantile Acquired Aphasia)" (medicinenet). Medscape part of WebMD Health Professional Network.

- Pearl PL, Carrazana EJ, Holmes GL (November 2001). "The Landau–Kleffner Syndrome". Epilepsy Curr. 1 (2): 39–45. doi:10.1046/j.1535-7597.2001.00012.x. PMC 320814. PMID 15309183.

- "Acquired Epileptic Aphasia" (medicinenet). Medscape Part of WebMD Health Professional Network. 2019-03-05.

- Tütüncüoğlu S, Serdaroğlu G, Kadioğlu B (October 2002). "Landau-Kleffner syndrome beginning with stuttering: case report". Journal of Child Neurology. 17 (10): 785–8. doi:10.1177/08830738020170101808. PMID 12546439. S2CID 3173640.

- Guevara-Campos J, González-de Guevara L (2007). "Landau–Kleffner syndrome: an analysis of 10 cases in Venezuela". Rev Neurol (in Spanish). 44 (11): 652–6. PMID 17557221.

- Sinclair DB, Snyder TJ (May 2005). "Corticosteroids for the treatment of Landau–Kleffner syndrome and continuous spike-wave discharge during sleep". Pediatr. Neurol. 32 (5): 300–6. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.12.006. PMID 15866429.

- Santos LH, Antoniuk SA, Rodrigues M, Bruno S, Bruck I (June 2002). "Landau–Kleffner syndrome: study of four cases". Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 60 (2–A): 239–41. doi:10.1590/s0004-282x2002000200010. PMID 12068352.

- Grote CL, Van Slyke P, Hoeppner JA (March 1999). "Language outcome following multiple subpial transection for Landau–Kleffner syndrome". Brain. 122 (3): 561–6. doi:10.1093/brain/122.3.561. PMID 10094262.

- Morrell F, Whisler WW, Smith MC, et al. (December 1995). "Landau-Kleffner syndrome. Treatment with subpial intracortical transection". Brain. 118 ( Pt 6): 1529–46. doi:10.1093/brain/118.6.1529. PMID 8595482.

- Sawhney IM, Robertson IJ, Polkey CE, Binnie CD, Elwes RD (March 1995). "Multiple subpial transection: a review of 21 cases". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 58 (3): 344–9. doi:10.1136/jnnp.58.3.344. PMC 1073374. PMID 7897419.

- Duran MH, Guimarães CA, Medeiros LL, Guerreiro MM (January 2009). "Landau-Kleffner syndrome: long-term follow-up". Brain Dev. 31 (1): 58–63. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2008.09.007. PMID 18930363. S2CID 25248883.

Further reading

- "Landau–Kleffner syndrome information page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 2007-02-13. Archived from the original on 2007-08-21. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- "Landau–Kleffner syndrome". National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders. 2002. Archived from the original on 2007-08-13. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- Rotenberg J, Pearl PL (2003). "Landau–Kleffner syndrome". Arch Neurol. 60 (7): 1019–21. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.7.1019. PMID 12873863.