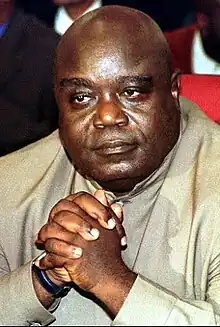

Laurent-Désiré Kabila

Laurent-Désiré Kabila (French pronunciation: [lo.ʁɑ̃ de.zi.ʁe ka.bi.la]) (27 November 1939 – 16 January 2001)[1][2] or more succinctly, Laurent Kabila (US: ⓘ), was a Congolese revolutionary and politician who served as the third President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1997 until his assassination in 2001.[3]

Laurent-Désiré Kabila | |

|---|---|

Kabila in 1997 | |

| 3rd President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| In office 17 May 1997 – 16 January 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Mobutu Sese Seko (as President of Zaire) |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Kabila |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 27 November 1939 Baudouinville or Jadotville, Belgian Congo |

| Died | 18 January 2001 (aged 61) Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Manner of death | Assassination |

| Nationality | Congolese |

| Political party | People's Revolution Party (1967–1996) Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (1996–1997) Independent (1997–2001) |

| Spouse | Sifa Mahanya |

| Children | at least 9 or 10 (including Joseph Kabila, Jaynet Kabila, Zoé Kabila and Aimée Kabila Mulengela) |

| Alma mater | University of Dar es Salaam |

| Profession | Rebel leader, President |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Battles/wars | |

A longtime opponent of Mobutu Sese Seko, he led the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (ADFLC), a Rwandan and Ugandan-sponsored rebel group that invaded Zaire and overthrew Mobutu during the First Congo War from 1996 to 1997. Having now become the new president of the country, whose name was changed back to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kabila found himself in a delicate position as a puppet of his foreign backers. The following year, he ordered the departure of all foreign troops from the country following the Kasika massacre to prevent a potential coup, leading to the Second Congo War in which his former Rwandan and Ugandan allies began sponsoring several rebel groups to overthrow him including the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD) and the Movement for the Liberation of the Congo (MLC). During the war, he was assassinated by one of his bodyguards, and was succeeded ten days later by his 29-year-old son Joseph.[4]

Early life

Kabila was born to the Luba people in Baudouinville, Katanga Province, (now Moba, Tanganyika Province), or Jadotville, Katanga Province, (now Likasi, Haut-Katanga Province) in the Belgian Congo.[5] His father was a Luba and his mother was a Lunda; his father's ethnicity was defining in the patriarchal kinship system. It is claimed that he studied abroad (political philosophy in Paris, got a PhD in Tashkent, in Belgrade and at last in Dar es Salaam), but no proof has been found or provided.[6]

Political activities

Congo crisis

Shortly after the Congo achieved independence in 1960, Katanga seceded under the leadership of Moïse Tshombe. Kabila organised the Baluba in an anti-secessionist rebellion in Manono. In September 1962 a new province, North Katanga, was established. He became a member of the provincial assembly[7] and served as chief of cabinet for Minister of Information Ferdinand Tumba.[8] In September 1963 he and other young members of the assembly were forced to resign, facing allegations of communist sympathies.[7]

Kabila established himself as a supporter of hard-line Lumumbist Prosper Mwamba Ilunga. When the Lumumbists formed the Conseil National de Libération, he was sent to eastern Congo to help organize a revolution, in particular in the Kivu and North Katanga provinces. This revolution was part of the larger Simba rebellions happening in the provinces at the time.[9] In 1965, Kabila set up a cross-border rebel operation from Kigoma, Tanzania, across Lake Tanganyika.[8]

Che Guevara

Kabila met Che Guevara for the first time in April 1965 where Guevara had appeared in the Congo with approximately 100 Cuban men who envisaged to bring about a Cuban-style revolution to overthrow the Congolese government. Guevara assisted Kabila and his rebel forces for a few months before Guevara judged Kabila (then age 26) as "not the man of the hour" he had alluded to, being too distracted and his men poorly trained and disciplined. This, in Guevara's opinion, accounted for Kabila showing up days late at times to provide supplies, aid, or backup to Guevara's men. Kabila preferred to spend most of his time at local bars or brothels instead of training his men or fighting the Congolese government forces. The lack of cooperation between Kabila and Guevara contributed to the suppression of the revolt in November that same year.[10]

In Guevara's view, of all of the people he met during his campaign in Congo, only Kabila had "genuine qualities of a mass leader"; but Guevara castigated Kabila for a lack of "revolutionary seriousness". After the failure of the rebellion, Kabila turned to smuggling gold and timber on Lake Tanganyika. He also ran a bar and brothel in Kigoma, Tanzania.[11][12]

Marxist mini-state (1967–1988)

In 1967, Kabila and his remnant of supporters moved their operation into the mountainous Fizi – Baraka area of South Kivu in the Congo, and founded the People's Revolutionary Party (PRP). With the support of the People's Republic of China, the PRP created a secessionist Marxist state in South Kivu province, west of Lake Tanganyika.[4]

The PRP state came to an end in 1988 and Kabila disappeared and was widely believed to be dead. While in Kampala, Kabila reportedly met Yoweri Museveni, the future president of Uganda. Museveni and former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere later introduced Kabila to Paul Kagame, who would become president of Rwanda. These personal contacts became vital in mid-1990s, when Uganda and Rwanda sought a Congolese face for their intervention in Zaire.[13][14]

First Congo War

As Rwandan Hutu refugees fled to Congo (then Zaire) after the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, refugee camps along the Zaire-Rwanda border became militarized with Hutu militia vowing to retake power in Rwanda. The Kigali regime considered these militias as a security threat and was seeking a way to dismantle those refugee camps. After Kigali had expressed its security concerns to Kinshasa, requesting that refugee camps get moved further inside the country, and Kinshasa ignored these concerns, Kigali believed that only military option could solve the issue. However, a military operation inside Zaire was likely be seen by the international community as an invasion.[15] A plan was put in place to foment a rebellion that would serve as a cover. The Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (AFDL) was then born with Rwanda's blessing, and with Kabila as its spokesperson.

By mid-1997, the AFDL had almost completely overrun the country and the remains of Mobutu's army. Only the country's decrepit infrastructure slowed Kabila's forces down; in many areas, the only means of transit were irregularly used dirt paths.[16] Following failed peace talks held on board of the South African ship SAS Outeniqua, Mobutu fled into exile on 16 May.

The next day, from his base in Lubumbashi, Kabila declared victory and installed himself as president. Kabila suspended the Constitution and changed the name of the country from Zaire to the Democratic Republic of the Congo—the country's official name from 1964 to 1971. He made his grand entrance into Kinshasa on 20 May and was sworn in on 31 May, officially commencing his tenure as president.

Presidency (1997–2001)

.svg.png.webp)

Kabila had been a committed Marxist, but his policies at this point were social democratic. He declared that elections would not be held for two years, since it would take him at least that long to restore order. While some in the West hailed Kabila as representing a "new breed" of African leadership, critics charged that Kabila's policies differed little from his predecessor's, being characterised by authoritarianism, corruption, and human rights abuses. As early as late 1997, Kabila was being denounced as "another Mobutu". Kabila was also accused trying to set up a personality cult. Mobutu's former minister of information, Dominique Sakombi Inongo, was retained by Kabila; he branded Kabila as "the Mzee," and created posters reading "Here is the man we needed" (French: Voici l'homme que nous avions besoin) appeared all over the country. [17]

By 1998, Kabila's former allies in Uganda and Rwanda had turned against him and backed a new rebellion of the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD), the Second Congo War. Kabila found new allies in Angola, Namibia and Zimbabwe, and managed to hold on in the south and west of the country and by July 1999, peace talks led to the withdrawal of most foreign forces.

Assassination

On January 16, 2001, Kabila was shot in his office at the Palais de Marbre and subsequently transported to Zimbabwe for medical treatment.[18] The DRC's authorities managed to keep power, despite Kabila's assassination. The exact circumstances are still contested. Kabila reportedly died on the spot, according to DRC's then-health minister Leonard Mashako Mamba, who was in the next door office when Kabila was shot and arrived immediately after the assassination. The government claimed that Kabila was still alive, however, and he was flown to a hospital in Zimbabwe after he was shot so that DRC authorities could organize the succession.[4]

The Congolese government announced that he had died of his wounds on 18 January.[19] One week later, his body was returned to Congo for a state funeral and his son, Joseph Kabila, became president ten days later.[20] By doing so, DRC officials were accomplishing the "verbal testimony" of the deceased President. Then Justice Minister Mwenze Kongolo and Kabila's aide-de-camp Eddy Kapend reported that Kabila had told them that his son Joseph, then number two of the army, should take over, if he were to die in office.

The investigation into Kabila's assassination led to 135 people, including four children, being tried before a special military tribunal. The alleged ringleader, Colonel Eddy Kapend (one of Kabila's cousins), and 25 others were sentenced to death in January 2003, but not executed. Of the remaining defendants, 64 were incarcerated, with sentences from six months to life, and 45 were exonerated. Some individuals were also accused of being involved in a plot to overthrow his son. Among them was Kabila's special advisor Emmanuel Dungia, former ambassador to South Africa. Many people believe the trial was flawed and the convicted defendants innocent; doubts are summarized in an Al Jazeera investigative film, Murder in Kinshasa.[21][22]

In January 2021, DRC's President Félix Tshisekedi pardoned all those convicted in the murder of Laurent-Désiré Kabila in 2001. Colonel Eddy Kapend and his co-defendants, who have been incarcerated for 15 years, were released.[23]

Personal life

He had at least nine children with his wife Sifa Mahanya: Josephine, Cécile, Fifi, Selemani, twins Jaynet and Joseph, Zoé, Anina and Tetia. He was also the alleged father of Aimée Kabila Mulengela whose mother is Zaïna Kibangula.

Citations

- Defense & Foreign Affairs Handbook. Perth Corporation. 2002. p. 380. ISBN 978-1-892998-06-4.

- Rabaud, Marlène; Zajtman, Arnaud (2011). "Murder in Kinshasa: who killed Laurent Désiré Kabila?".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "IRIN – In Depth Reports". IRIN. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- John C. Fredriksen, ed. Biographical Dictionary of Modern World Leaders (2003) pp 239–240.

- Erik Kennes (1 October 2003). Essai biographique sur Laurent Désiré Kabila: Cahiers 57-58-59. Editions L'Harmattan. p. 13. ISBN 978-2-296-31958-5. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

Quant au lieu de naissance du futur Président, plusieurs sources fiables confirment Jadotville [...] Certains affirment qu'il est né à Baudouinville (>Moba), ce qui paraît très peu probable.

- "L'obscur M. Kabila". L'Express. 25 June 1998. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- Colvin 1968, p. 169.

- Dunn 2004, p. 54.

- Van Reybrouck, David (2014). Congo : the epic history of a people. Garrett, Sam. London. p. 322. ISBN 9780007562916. OCLC 875627937.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Mfi Hebdo". Rfi.fr. 6 July 2009. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Laurent Kabila". The Economist. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- Meredith, Martin (2005). The fate of Africa : from the hopes of freedom to the heart of despair : a history of fifty years of independence (1st ed.). New York: Public Affairs. p. 150. ISBN 1-58648-246-7. OCLC 58791298.

- Dunn 2004, p. 55.

- "Mfi Hebdo". Rfi.fr. 6 July 2009. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- Lokongo, Antoine (September 2000). "The suffering of Congo". New African. No. 388. p. 20. ISSN 0140-833X. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- Dickovick, J. Tyler (2008). The World Today Series: Africa 2012. Lanham, Maryland: Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 978-1-61048-881-5.

- Edgerton, Robert (18 December 2002). The Troubled Heart of Africa: A History of the Congo. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-30486-2.

- Jeffries, Stuart (11 February 2001). "Revealed: how Africa's dictator died at the hands of his boy soldiers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Official SADC Trade, Industry, and Investment Review. Southern African Marketing Company. 2006. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-620-36351-8. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- Onishi, Norimitsu (27 January 2001). "Glimpse of New President as Joseph Kabila Takes Oath in Congo". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- Special programme. "Murder in Kinshasa". Aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- Zajtman, Arnaud; Rabaud, Marlène. "Zone d'ombre autour d'un assassinat" (in French). Archived from the original on 5 July 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- Stanis Bujakera Tshiamala (5 January 2021). "DRC: Tshisekedi pardons those convicted in the killing of Laurent-Désiré Kabila". The Africa Report. Archived from the original on 8 February 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

References

- Colvin, Ian Goodhope (1968). The rise and fall of Moise Tshombe: a biography. London: Ferwin. ISBN 9780090876501. OCLC 752436625.

- Dunn, Kevin C. (2004). "A Survival Guide to Kinshasa: Lessons of the Father, Passed Down to the Son". In John F. Clark (ed.). The African Stakes of the Congo War. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 1-4039-6723-7.

Further reading

- Boya, Odette M. "Contentious Politics and Social Change in Congo." Security Dialogue 32.1 (2001): 71–85.

- Fredriksen, John C. ed. Biographical Dictionary of Modern World Leaders (2003) pp 239–240.

- Kabuya-Lumuna Sando, C. (2002). "Laurent Désiré Kabila". Review of African Political Economy. 29 (93/4): 616–9. doi:10.1080/03056240208704645. JSTOR 4006803. S2CID 152898226.

- Rosenblum, R. "Kabila's Congo." Current History 97 (May 1998) pp 193–198.

- Scharzberg, Michael G. "Beyond Mobutu: Kabila and the Congo." Journal of Democracy, 8 (October 1997): 70–84.

- Weiss, Herbert. "Civil war in the Congo." Society 38.3 (2001): 67–71.

- Cosma, Wilungula B. (1997). Fizi, 1967-1986: Le maquis Kabila. Paris: Institut africain-CEDAF.

External links

- Kabila Legacy by Human Rights Watch

- Retracing Che Guevara's Congo Footsteps by BBC News, November 25, 2004