Law of truly large numbers

The law of truly large numbers (a statistical adage), attributed to Persi Diaconis and Frederick Mosteller, states that with a large enough number of independent samples, any highly implausible (i.e. unlikely in any single sample, but with constant probability strictly greater than 0 in any sample) result is likely to be observed.[1] Because we never find it notable when likely events occur, we highlight unlikely events and notice them more. The law is often used to falsify different pseudo-scientific claims; as such, it is sometimes criticized by fringe scientists.[2][3] Similar theorem but bolder (for infinite numbers) is Infinite Monkey Theorem it shows that any finite pattern is possible to get, through infinite random process (but in this case there is skepticism about physical applicability of such arrangements because of finite nature of observable universe).[4]

The law is meant to make a statement about probabilities and statistical significance: in large enough masses of statistical data, even minuscule fluctuations attain statistical significance. Thus in truly large numbers of observations, it is paradoxically easy to find significant correlations, in large numbers, which still do not lead to causal theories (see: spurious correlation), and which by their collective number,[5] might lead to obfuscation as well.

The law can be rephrased as "large numbers also deceive", something which is counter-intuitive to a descriptive statistician. More concretely, skeptic Penn Jillette has said, "Million-to-one odds happen eight times a day in New York" (population about 8,000,000).[6]

Examples

For a simplified example of the law, assume that a given event happens with a probability for its occurrence of 0.1%, within a single trial. Then, the probability that this so-called unlikely event does not happen (improbability) in a single trial is 99.9% (0.999).

For a sample of only 1000 independent trials, however, the probability that the event does not happen in any of them, even once (improbability), is only[7] 0.9991000 ≈ 0.3677, or 36.77%. Then, the probability that the event does happen, at least once, in 1000 trials is ( 1 − 0.9991000 ≈ 0.6323, or ) 63.23%. This means that this "unlikely event" has a probability of 63.23% of happening if 1000 independent trials are conducted. If the number of trials were increased to 10,000, the probability of it happening at least once in 10,000 trials rises to ( 1 − 0.99910000 ≈ 0.99995, or ) 99.995%. In other words, a highly unlikely event, given enough independent trials with some fixed number of draws per trial, is even more likely to occur.

For an event X that occurs with very low probability of 0.0000001% (in any single sample, see also almost never), considering 1,000,000,000 as a "truly large" number of independent samples gives the probability of occurrence of X equal to 1 − 0.9999999991000000000 ≈ 0.63 = 63% and a number of independent samples equal to the size of the human population (in 2021) gives probability of event X: 1 − 0.9999999997900000000 ≈ 0.9996 = 99.96%.[8]

These calculations can be formalized in mathematical language as: "the probability of an unlikely event X happening in N independent trials can become arbitrarily near to 1, no matter how small the probability of the event X in one single trial is, provided that N is truly large."[9]

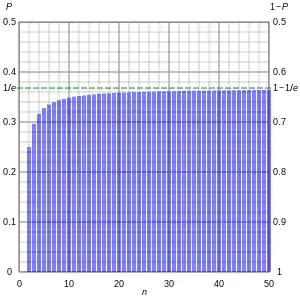

For example, where the probability of unlikely event X is not a small constant but decreased in function of N, see graph.

In sexual reproduction, the chances for a microscopic, single spermatozoon to reach the ovum in order to fertilize it is very small. Thus, in every encounter, spermatozoa are released in numbers of millions at once (in mammals), raising the opportunities of fecundation to a nearly-certain event.

In high availability systems even very unlikely events have to be taken into consideration, in series systems even when the probability of failure for single element is very low after connecting them in large numbers probability of whole system failure raises (to make system failures less probable redundancy can be used - in such parallel systems even highly unreliable redundant parts connected in large numbers raise the probability of not breaking to required high level).[10]

In criticism of pseudoscience

The law comes up in criticism of pseudoscience and is sometimes called the Jeane Dixon effect (see also Postdiction). It holds that the more predictions a psychic makes, the better the odds that one of them will "hit". Thus, if one comes true, the psychic expects us to forget the vast majority that did not happen (confirmation bias).[11] Humans can be susceptible to this fallacy.

Another similar manifestation of the law can be found in gambling, where gamblers tend to remember their wins and forget their losses,[12] even if the latter far outnumbers the former (though depending on a particular person, the opposite may also be true when they think they need more analysis of their losses to achieve fine tuning of their playing system[13]). Mikal Aasved links it with "selective memory bias", allowing gamblers to mentally distance themselves from the consequences of their gambling[13] by holding an inflated view of their real winnings (or losses in the opposite case – "selective memory bias in either direction").

See also

Notes

- Everitt 2002

- Beitman, Bernard D., (15 Apr 2018), Intrigued by the Low Probability of Synchronicities? Coincidence theorists and statisticians dispute the meaning of rare events. at PsychologyToday

- Sharon Hewitt Rawlette, (2019), Coincidence or Psi? The Epistemic Import of Spontaneous Cases of Purported Psi Identified Post-Verification, Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 9–42

- Kittel, Charles; Kroemer, Herbert (1980). Thermal Physics (2nd ed.). San Fransisco: W.H. Freeman Company. p. 53. ISBN 0-7167-1088-9. OCLC 5171399.

- Tyler Vigen, 2015, Spurious Correlations Correlation does not equal causation, book website with examples

- Kida, Thomas E. (Thomas Edward) (2006). Don't believe everything you think : the 6 basic mistakes we make in thinking. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. p. 97. ISBN 1615920056. OCLC 1019454221.

- here other law of "Improbability principle" also acts - the "law of probability lever", which is (according to David Hand) a kind of butterfly effect: we have a value "close" to 1 raised to large number what gives "surprisingly" low value or even close to zero if this number is larger, this shows some philosophical implications, questions the theoretical models but it does not render them useless - evaluation and testing of theoretical hypothesis (even when probability of it correctness is close to 1) can be its falsifiability - feature widely accepted as important for the scientific inquiry which is not meant to lead to dogmatic or absolute knowledge, see: statistical proof.

- Graphing calculator at Desmos (graphing)

- Proof in: Elemér Elad Rosinger, (2016), "Quanta, Physicists, and Probabilities ... ?" page 28

- Reliability of Systems in Concise Reliability for Engineers, Jaroslav Menčík, 2016

- 1980, Austin Society to Oppose Pseudoscience (ASTOP) distributed by ICSA (former American Family Foundation) "Pseudoscience Fact Sheets, ASTOP: Psychic Detectives"

- Daniel Freeman, Jason Freeman, 2009, London, "Know Your Mind: Everyday Emotional and Psychological Problems and How to Overcome Them" p. 41

- Mikal Aasved, 2002, Illinois, The Psychodynamics and Psychology of Gambling: The Gambler's Mind vol. I, p. 129

References

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Law of truly large numbers". MathWorld.

- Diaconis, P.; Mosteller, F. (1989). "Methods of Studying Coincidences" (PDF). Journal of the American Statistical Association. 84 (408): 853–61. doi:10.2307/2290058. JSTOR 2290058. MR 1134485. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-12. Retrieved 2009-04-28.

- Everitt, B.S. (2002). Cambridge Dictionary of Statistics (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-0521810999.

- David J. Hand, (2014), The Improbability Principle: Why Coincidences, Miracles, and Rare Events Happen Every Day