Southeast Missouri Lead District

The Southeast Missouri Lead District, commonly called the Lead Belt, is a lead mining district in the southeastern part of Missouri. Counties in the Lead Belt include Saint Francois, Crawford, Dent, Iron, Madison, Reynolds, and Washington. This mining district is the most important and critical lead producer in the United States.[1][2]

History

The potential for lead mining in Southeast Missouri was first discovered and documented in 1700 by Father James Gravier.[2] Philip Francois Renault of France led a large exploratory mission in 1719 and started mining operations in Old Mines and Mine La Motte in 1720, establishing the first lead mining subdistrict of Mine LaMotte-Fredericktown.[2]

Between the 1750s and 1799, production of lead in the region decreased. In 1799, Moses Austin settled in Potosi, originally known as Mine a Breton, bringing new mining methods and practices that revitalized lead mining in the district.[2] Austin was the first to sink deep mine shafts and start smelting operations, dramatically increasing lead production. Before this time, lead mines had been surface or near-surface mines of less than 10 feet in depth. In 1808, Moses Austin and Samuel Hammond established the city of Herculaneum as a shipping point closer to the mining region, replacing Ste. Genevieve as the main shipping point to and from the mining district on the Mississippi River.[2]

The Old Lead Belt Subdistrict was established in 1864 with the opening of the Bonne Terre Mine by the St. Joseph Lead Company.[2] Notable mines in the subdistrict region included the Bonne Terre Mine, and mines near Doe Run, Desloge, Flat River (Park Hills), and Leadwood. In 1972, the last Old Lead Belt mine at Flat River closed, ending 108 years of lead mining in the Old Lead Belt.

The area of mining has changed over the years. The Old Lead Belt is centered on Park Hills and Desloge, while the New Lead Belt or Viburnum Trend is near Viburnum. The Irish Wilderness in Ripley and Oregon Counties has significant lead ore; however, this is a protected wilderness area. Significant among Missouri's lead mining concerns in the district was the Desloge family and Desloge Consolidated Lead Company in Desloge, Missouri and Bonne Terre—having been active in lead trading, mining and smelting from 1823 in Potosi to 1929. Lead mining operations were consolidated under the control of St. Joe Lead.

In the late 1940s, reserves in the Old Lead Belt began to decline, spurring new mineral exploration in the Southeast Missouri region. In 1955, the St. Joseph Lead Company discovered a new orebody near Viburnum, Missouri, leading to the opening of the Viburnum No. 27 Mine in 1960.[2] The St. Joseph Lead Company, Cominco, Kennecott Copper, Amax, Inc., and Asarco companies conducted exploration that led to the opening of 10 additional mines, establishing what is known today as the Viburnum Trend, also called the New Lead Belt.[2]

The Viburnum Trend is the only subdistrict mined for lead in the Southeast Missouri Lead District in modern day. Six lead mines are currently operational in 2022: the Brushy Creek, Buick, Casteel, Fletcher, and Sweetwater mines.[3]

Today, many of the mines and mills of the Old Lead Belt have been abandoned or repurposed. Bonne Terre has large subterranean mines, now used commercially for recreational tourism and scuba diving. The Missouri Mines State Historic Site occupies the retired Federal Mill No. 3 in Park Hills.

Mineralogy and geology

The formal geological name for the Lead Belt is the "Southeastern Missouri Mississippi Valley-type Mineral District." It contains the highest concentration of galena (lead(II) sulfide) in the world[2] as well as significant economic quantities of zinc, copper and silver and currently mined sub-economic quantities of metals such as cadmium, nickel and cobalt.[2] Most of the mined ore minerals are found as sulfides, with the primary ore minerals galena and sphalerite, with minor sulfides pyrite, chalcopyrite, bornite, enargite, millerite, and arsenopyrite.[2] Gangue minerals associated with the economic minerals include marcasite, calcite, dolomite, and quartz.

Sulfide and carbonate mineral specimens are highly prized by gem and mineral collectors and are found in museums worldwide.

The ore minerals of the Old Lead Belt are hosted in the dolomite of the lower Bonneterre Formation, and can extend into the underlying Lamotte Sandstone and rarely into the overlying Davis Formation. In the Viburnum Trend, lead-zinc ore mineralization is hosted in the bacterial stromatolite reefs dolomites of the upper Bonneterre Formation,[4] and most orebodies are concentrated in areas where the Lamotte Sandstone pinches out against Precambrian igneous knobs and ridges.[5] The Upper Cambrian age Bonneterre Formation was deposited in a shallow sea around the Precambrian age St. Francois Mountains, which formed an island archipelago. Ore mineralization most likely occurred during the Permian, when low-temperature hydrothermal metal-rich brines migrated through the Ozarks during the Ouachita orogeny in the Late Paleozoic.[6][7][4][5]

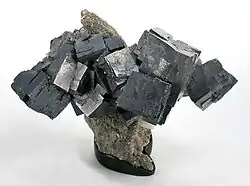

Ore mineralization in the Lead Belt occurred as part of the same mineralization event, however, the intensity of mineralization and depositional controls differ between the Viburnum Trend and Old Lead Belt.[8] In the Old Lead Belt, galena is more fine-grained and disseminated into the host rock, and large, euhedral crystals are rare. Ore is mostly constrained to the lower 60 feet of the Bonneterre Formation, and preferentially follow the lateral sedimentary beds and features. In the Viburnum Trend, zinc and copper are found in higher concentrations, and galena was able to form larger, more euhedral crystals. Ore mineralization in this subdistrict is prominently emplaced along collapse breccias, and not as influenced by lateral sedimentary features as in the Old Lead Belt. Ore in the Viburnum Trend can be found throughout the entire vertical extent of the Bonneterre Formation, but is mostly constrained to the upper 75 feet.[8]

Cubic galena (lead ore) from the Sweetwater Mine of the Viburnum Trend (Reynolds County, Missouri, USA).

Cubic galena (lead ore) from the Sweetwater Mine of the Viburnum Trend (Reynolds County, Missouri, USA). Sphalerite, galena, and marcasite from the Viburnum Trend District (Reynolds County, Missouri, USA).

Sphalerite, galena, and marcasite from the Viburnum Trend District (Reynolds County, Missouri, USA). Calcite and chalcopyrite specimen from the Brushy Creek Mine of the Viburnum Trend District (Reynolds County, Missouri, USA).

Calcite and chalcopyrite specimen from the Brushy Creek Mine of the Viburnum Trend District (Reynolds County, Missouri, USA).

Production

The Lead Belt produces about 70% of the US primary supply of lead, and significant amounts of the nation's zinc.[1] In the year 2000, Missouri produced 313,105 tons, with an estimated value of $128,838,880, according to Missouri DNR Data. About 84% of the lead is used for lead–acid batteries, and a secondary smelter in Boss, Missouri recycles lead–acid batteries. Another major consumer of Missouri lead is Winchester Ammunition, located in East Alton, Illinois.

From 1720 to its closure in 1959, the Mine La Motte-Fredericktown Subdistrict produced over 325,000 tons of lead. From 1864 to 1972, over 8.5 million tons of lead was produced from the Old Lead Belt Subdistrict.[2] The Viburnum Trend is the only subdistrict still in production, and is primarily mined by The Doe Run Company. From 1960 to 2022, The Doe Run Company has reported that nearly 315 million tons of ore has been extracted from the Viburnum Trend.[3]

Communities in the Lead Belt

- Arcadia

- Belgrade

- Bismarck

- Bonne Terre

- Boss

- Bourbon

- Bunker

- Cadet

- Caledonia

- Centerville

- Cobalt

- Cuba

- Davisville

- Desloge

- Doe Run

- Ellington

- Farmington

- Frankclay

- Fredericktown

- Irondale

- Ironton

- Leadington

- Leadwood

- Lesterville

- Mine La Motte

- Old Mines

- Park Hills

- Pilot Knob

- Potosi

- Reynolds

- Richwoods

- Salem

- Steelville

- Sullivan

- Viburnum

Politics

| Year | Democrat | Republican | Third Party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| 2020 | 14,510 | 20.83% | 54,183 | 77.78% | 965 | 1.39% |

| 2016 | 13,456 | 21.24% | 47,521 | 75.01% | 2,372 | 3.74% |

| 2012 | 21,196 | 35.53% | 37,046 | 62.09% | 1,420 | 2.38% |

| 2008 | 27,890 | 43.69% | 34,795 | 54.50% | 1,158 | 1.81% |

| 2004 | 26,282 | 43.26% | 34,061 | 56.06% | 414 | 0.68% |

| 2000 | 23,481 | 44.04% | 28,556 | 53.56% | 1,277 | 2.40% |

| 1996 | 25,135 | 49.72% | 17,817 | 35.24% | 7,601 | 15.04% |

| 1992 | 26,804 | 49.40% | 16,727 | 30.83% | 10,729 | 19.77% |

| 1988 | 23,744 | 50.05% | 23,561 | 49.67% | 134 | 0.28% |

| 1984 | 21,189 | 42.90% | 28,207 | 57.10% | 0 | 0% |

| 1980 | 23,329 | 44.41% | 27,817 | 52.95% | 1,389 | 2.64% |

| 1976 | 25,909 | 56.69% | 19,568 | 42.81% | 229 | 0.50% |

| 1972 | 14,673 | 35.35% | 26,830 | 64.65% | 0 | 0% |

| 1968 | 17,125 | 39.70% | 20,689 | 47.96% | 5,327 | 12.35% |

| 1964 | 28,062 | 64.04% | 15,760 | 35.96% | 0 | 0% |

| 1960 | 19,603 | 42% | 27,066 | 58% | 0 | 0% |

| 1956 | 21,208 | 45.02% | 25,903 | 54.98% | 0 | 0% |

| 1952 | 22,700 | 47.56% | 24,974 | 52.32% | 59 | 0.12% |

| 1948 | 22,019 | 55.88% | 17,300 | 43.90% | 88 | 0.22% |

| 1944 | 19,971 | 49.12% | 20,630 | 50.74% | 55 | 0.14% |

| 1940 | 24,156 | 49.54% | 24,515 | 50.28% | 87 | 0.18% |

| 1936 | 24,077 | 54.27% | 20,067 | 45.23% | 218 | 0.49% |

| 1932 | 24,822 | 60.51% | 15,836 | 38.60% | 365 | 0.89% |

| 1928 | 13,859 | 37.84% | 22,674 | 61.91% | 90 | 0.25% |

| 1924 | 16,619 | 49.22% | 16,399 | 48.57% | 745 | 2.21% |

| 1920 | 15,986 | 46.82% | 17,619 | 51.61% | 535 | 1.57% |

| 1916 | 11,384 | 51.45% | 10,262 | 46.38% | 479 | 2.16% |

| 1912 | 9,225 | 47.85% | 7,228 | 37.49% | 2,825 | 14.65% |

| 1908 | 10,166 | 46.97% | 10,675 | 49.32% | 803 | 3.71% |

| 1904 | 9,129 | 47.73% | 9,537 | 49.87% | 319 | 1.67% |

| 1900 | 10,056 | 53.36% | 8,575 | 45.51% | 213 | 1.13% |

| 1896 | 9,866 | 56.52% | 7,527 | 43.12% | 64 | 0.37% |

| 1892 | 8,681 | 57.71% | 6,102 | 40.56% | 260 | 1.73% |

| 1888 | 8,878 | 56.48% | 6,485 | 41.25% | 357 | 2.27% |

| 1884 | 8,097 | 61.16% | 5,055 | 38.19% | 86 | 0.65% |

| 1880 | 7,964 | 64.38% | 4,160 | 33.63% | 246 | 1.99% |

| 1876 | 7,697 | 68.82% | 3,461 | 30.94% | 27 | 0.24% |

| 1872 | 4,822 | 62.91% | 2,843 | 37.09% | 0 | 0% |

| 1868 | 2,199 | 54.31% | 1,850 | 45.69% | 0 | 0% |

| 1864 | 717 | 24.41% | 2,220 | 75.59% | 0 | 0% |

| 1860 | 2,380 | 43.19% | 211 | 3.83% | 2,920 | 52.98% |

| 1856 | 2,481 | 57.13% | 0 | 0% | 1,862 | 42.87% |

| 1852 | 1,594 | 60.38% | 1,046 | 39.62% | 0 | 0% |

| 1848 | 1,497 | 54.02% | 1,274 | 45.98% | 0 | 0% |

| 1844 | 1,588 | 54.35% | 1,334 | 45.65% | 0 | 0% |

| 1840 | 1,312 | 54.58% | 1,092 | 45.42% | 0 | 0% |

| 1836 | 703 | 58.29% | 503 | 41.71% | 0 | 0% |

| 1832 | Incomplete returns | Incomplete returns | Incomplete returns | |||

| 1828 | 816 | 70.89% | 335 | 29.11% | 0 | 0% |

See also

References

- "Southeast Missouri Mining and Milling". Doe Run Company. 2004. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2008/5140/pdf/Chapter1.pdf Seeger, Cheryl M., History of Mining in the Southeast Missouri Lead District and Description of Mine Processes, Regulatory Controls, Environmental Effects, and Mine Facilities in the Viburnum Trend Subdistrict in Kleeschulte, M.J., ed., 2008, Hydrologic investigations concerning lead mining issues in southeastern Missouri: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2008–5140, Chapter 1

- The Doe Run Company (March 2022). "Doe Run Backgrounder: About The Doe Run Company" (PDF). doerun.com. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- Sverjensky, Dimitri A. (November 1, 1981). "The origin of a mississippi valley-type deposit in the Viburnum Trend, Southeast Missouri". Economic Geology. 76 (7): 1848–1872. Bibcode:1981EcGeo..76.1848S. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.76.7.1848. ISSN 1554-0774.

- Kisvarsanyi, G. (May 1, 1977). "The role of the Precambrian igneous basement in the formation of the stratabound lead-zinc-copper deposits in Southeast Missouri". Economic Geology. 72 (3): 435–442. Bibcode:1977EcGeo..72..435K. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.72.3.435. ISSN 1554-0774.

- Guilbert, John M. and Charles F. Park, Jr., The Geology of Ore Deposits, Freeman, 1986 pp. 890-901 ISBN 0-7167-1456-6

- Appold, Martin S.; Garven, Grant (September 1, 1999). "The hydrology of ore formation in the Southeast Missouri District; numerical models of topography-driven fluid flow during the Ouachita Orogeny". Economic Geology. 94 (6): 913–935. Bibcode:1999EcGeo..94..913A. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.94.6.913. ISSN 1554-0774.

- Ohle, Ernest L. (December 1, 1990). "A comparison of the old lead belt and the new lead belt in Southeast Missouri". Economic Geology. 85 (8): 1894–1895. Bibcode:1990EcGeo..85.1894O. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.85.8.1894. ISSN 1554-0774.