Symmedian

In geometry, symmedians are three particular lines associated with every triangle. They are constructed by taking a median of the triangle (a line connecting a vertex with the midpoint of the opposite side), and reflecting the line over the corresponding angle bisector (the line through the same vertex that divides the angle there in half). The angle formed by the symmedian and the angle bisector has the same measure as the angle between the median and the angle bisector, but it is on the other side of the angle bisector.

The three symmedians meet at a triangle center called the Lemoine point. Ross Honsberger has called its existence "one of the crown jewels of modern geometry".[1]

Isogonality

Many times in geometry, if we take three special lines through the vertices of a triangle, or cevians, then their reflections about the corresponding angle bisectors, called isogonal lines, will also have interesting properties. For instance, if three cevians of a triangle intersect at a point P, then their isogonal lines also intersect at a point, called the isogonal conjugate of P.

The symmedians illustrate this fact.

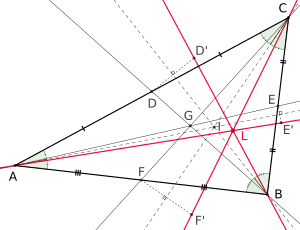

- In the diagram, the medians (in black) intersect at the centroid G.

- Because the symmedians (in red) are isogonal to the medians, the symmedians also intersect at a single point, L.

This point is called the triangle's symmedian point, or alternatively the Lemoine point or Grebe point.

The dotted lines are the angle bisectors; the symmedians and medians are symmetric about the angle bisectors (hence the name "symmedian.")

Construction of the symmedian

Let △ABC be a triangle. Construct a point D by intersecting the tangents from B and C to the circumcircle. Then AD is the symmedian of △ABC.[2]

first proof. Let the reflection of AD across the angle bisector of ∠BAC meet BC at M'. Then:

second proof. Define D' as the isogonal conjugate of D. It is easy to see that the reflection of CD about the bisector is the line through C parallel to AB. The same is true for BD, and so, ABD'C is a parallelogram. AD' is clearly the median, because a parallelogram's diagonals bisect each other, and AD is its reflection about the bisector.

third proof. Let ω be the circle with center D passing through B and C, and let O be the circumcenter of △ABC. Say lines AB, AC intersect ω at P, Q, respectively. Since ∠ABC = ∠AQP, triangles △ABC and △AQP are similar. Since

we see that PQ is a diameter of ω and hence passes through D. Let M be the midpoint of BC. Since D is the midpoint of PQ, the similarity implies that ∠BAM = ∠QAD, from which the result follows.

fourth proof. Let S be the midpoint of the arc BC. |BS| = |SC|, so AS is the angle bisector of ∠BAC. Let M be the midpoint of BC, and It follows that D is the Inverse of M with respect to the circumcircle. From that, we know that the circumcircle is an Apollonian circle with foci M, D. So AS is the bisector of angle ∠DAM, and we have achieved our wanted result.

Tetrahedra

The concept of a symmedian point extends to (irregular) tetrahedra. Given a tetrahedron ABCD two planes P, Q through AB are isogonal conjugates if they form equal angles with the planes ABC and ABD. Let M be the midpoint of the side CD. The plane containing the side AB that is isogonal to the plane ABM is called a symmedian plane of the tetrahedron. The symmedian planes can be shown to intersect at a point, the symmedian point. This is also the point that minimizes the squared distance from the faces of the tetrahedron.[3]

References

- Honsberger, Ross (1995), "Chapter 7: The Symmedian Point", Episodes in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Euclidean Geometry, Washington, D.C.: Mathematical Association of America.

- Yufei, Zhao (2010). Three Lemmas in Geometry (PDF). p. 5.

- Sadek, Jawad; Bani-Yaghoub, Majid; Rhee, Noah (2016), "Isogonal Conjugates in a Tetrahedron" (PDF), Forum Geometricorum, 16: 43–50.