Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard (/ˈsɪlɑːrd/; Hungarian: Szilárd Leó, pronounced [ˈsilaːrd ˈlɛoː]; born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-American physicist and inventor. He conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea in 1936, and in late 1939 wrote the letter for Albert Einstein's signature that resulted in the Manhattan Project that built the atomic bomb. According to György Marx, he was one of the Hungarian scientists known as The Martians.[1]

Leo Szilard | |

|---|---|

Szilard, c. 1960 | |

| Born | Leó Spitz February 11, 1898 |

| Died | May 30, 1964 (aged 66) San Diego, California, US |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics, biology |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Über die thermodynamischen Schwankungserscheinungen (1923) |

| Doctoral advisor | Max von Laue |

| Other academic advisors | Albert Einstein |

| Signature | |

Together with Enrico Fermi, he applied for a nuclear reactor patent in 1944. In addition to the nuclear reactor, Szilard coined and submitted the earliest known patent applications and the first publications for the concept of the electron microscope (1928), he also contributed to the development of the linear accelerator (1928), and the cyclotron (1929) in Germany. Between 1926 and 1930, he worked with Einstein on the development of the Einstein refrigerator. His inventions, discoveries, and contributions related to biological science are also equally important, they include the discovery of feedback inhibition and the invention of the chemostat. According to Theodore Puck and Philip I. Marcus, Szilard gave essential advice which made the earliest cloning of the human cell a reality.

Szilard initially attended Palatine Joseph Technical University in Budapest, but his engineering studies were interrupted by service in the Austro-Hungarian Army during World War I. He left Hungary for Germany in 1919, enrolling at Technische Hochschule (Institute of Technology) in Berlin-Charlottenburg, but became bored with engineering and transferred to Friedrich Wilhelm University, where he studied physics. He wrote his doctoral thesis on Maxwell's demon, a long-standing puzzle in the philosophy of thermal and statistical physics. Szilard was the first scientist of note to recognize the connection between thermodynamics and information theory.

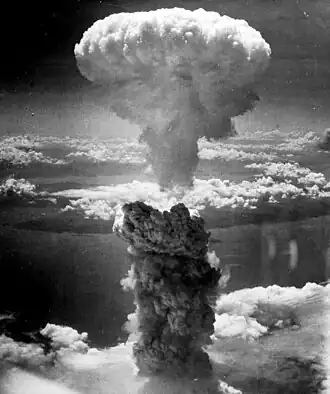

After Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany in 1933, Szilard urged his family and friends to flee Europe while they still could. He moved to England, where he helped found the Academic Assistance Council, an organization dedicated to helping refugee scholars find new jobs. While in England he discovered a means of isotope separation known as the Szilard–Chalmers effect. Foreseeing another war in Europe, Szilard moved to the United States in 1938, where he worked with Enrico Fermi and Walter Zinn on means of creating a nuclear chain reaction. He was present when this was achieved within the Chicago Pile-1 on December 2, 1942. He worked for the Manhattan Project's Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago on aspects of nuclear reactor design. He drafted the Szilard petition advocating a demonstration of the atomic bomb, but the Interim Committee chose to use them against cities without warning.

He publicly sounded the alarm against the possible development of salted thermonuclear bombs, a new kind of nuclear weapon that might annihilate mankind. Diagnosed with bladder cancer in 1960, he underwent a cobalt-60 treatment that he had designed. He helped found the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, where he became a resident fellow. Szilard founded Council for a Livable World in 1962 to deliver "the sweet voice of reason" about nuclear weapons to Congress, the White House, and the American public. He died in his sleep of a heart attack in 1964.

Early life

He was born as Leó Spitz in Budapest, Kingdom of Hungary, on February 11, 1898. His middle-class Jewish parents, Lajos (Louis) Spitz, a civil engineer, and Tekla Vidor, raised Leó on the Városligeti Fasor in Pest.[2] He had two younger siblings, a brother, Béla, born in 1900, and a sister, Rózsi, born in 1901. On October 4, 1900, the family changed its surname from the German "Spitz" to the Hungarian "Szilárd", a name that means "solid" in Hungarian.[3] Despite having a religious background, Szilard became an agnostic.[4][5] From 1908 to 1916 he attended the Lutheran gymnasium school in his home town along with others such as Edward Teller.[6] Showing an early interest in physics and a proficiency in mathematics, in 1916 he won the Eötvös Prize, a national prize for mathematics.[7][8]

With World War I raging in Europe, Szilard received notice on January 22, 1916, that he had been drafted into the 5th Fortress Regiment, but he was able to continue his studies. He enrolled as an engineering student at the Palatine Joseph Technical University, which he entered in September 1916. The following year he joined the Austro-Hungarian Army's 4th Mountain Artillery Regiment, but immediately was sent to Budapest as an officer candidate. He rejoined his regiment in May 1918 but in September, before being sent to the front, he fell ill with Spanish Influenza and was returned home for hospitalization.[10] Later he was informed that his regiment had been nearly annihilated in battle, so the illness probably saved his life.[11] He was discharged honorably in November 1918, after the Armistice.[12]

In January 1919, Szilard resumed his engineering studies, but Hungary was in a chaotic political situation with the rise of the Hungarian Soviet Republic under Béla Kun. Szilard and his brother Béla founded their own political group, the Hungarian Association of Socialist Students, with a platform based on a scheme of Szilard's for taxation reform. He was convinced that socialism was the answer to Hungary's post-war problems, but not that of Kun's Hungarian Socialist Party, which had close ties to the Soviet Union.[13] When Kun's government tottered, the brothers officially changed their religion from "Israelite" to "Calvinist", but when they attempted to re-enroll in what was now the Budapest University of Technology, they were prevented from doing so by nationalist students because they were Jews.[14]

Time in Berlin

Convinced that there was no future for him in Hungary, Szilard left for Berlin via Austria on December 25, 1919, and enrolled at the Technische Hochschule (Institute of Technology) in Berlin-Charlottenburg. He was soon joined by his brother Béla.[15] Szilard became bored with engineering, and his attention turned to physics. This was not taught at the Technische Hochschule, so he transferred to Friedrich Wilhelm University, where he attended lectures given by Albert Einstein, Max Planck, Walter Nernst, James Franck and Max von Laue.[16] He also met fellow Hungarian students Eugene Wigner, John von Neumann and Dennis Gabor.[17]

Szilard's doctoral dissertation on thermodynamics Über die thermodynamischen Schwankungserscheinungen (On The Manifestation of Thermodynamic Fluctuations), praised by Einstein, won top honors in 1922. It involved a long-standing puzzle in the philosophy of thermal and statistical physics known as Maxwell's demon, a thought experiment originated by the physicist James Clerk Maxwell. The problem was thought to be insoluble, but in tackling it Szilard recognized the connection between thermodynamics and information theory.[18][19] Szilard was appointed as assistant to von Laue at the Institute for Theoretical Physics in 1924. In 1927 he finished his habilitation and became a Privatdozent (private lecturer) in physics. For his habilitation lecture, he produced a second paper on Maxwell's Demon, Über die Entropieverminderung in einem thermodynamischen System bei Eingriffen intelligenter Wesen (On the reduction of entropy in a thermodynamic system by the intervention of intelligent beings), that had actually been written soon after the first. This introduced the thought experiment now called the Szilard engine and became important in the history of attempts to understand Maxwell's demon. The paper is also the first equation of negative entropy and information. As such, it established Szilard as one of the founders of information theory, but he did not publish it until 1929, and did not pursue it further.[20][21] Cybernetics, via the work of Norbert Wiener and Claude E. Shannon, would later develop the concept into a general theory in the 1940s and 1950s—though, during the time of the Cybernetics Meetings, John Von Neumann pointed out that Szilard first equated information with entropy in his review of Wiener's Cybernetics book.[22][23]

Throughout his time in Berlin, Szilard worked on numerous technical inventions. In 1928 he submitted a patent application for the linear accelerator, not knowing of Gustav Ising's prior 1924 journal article and Rolf Widerøe's operational device,[24][25] and in 1929 applied for one for the cyclotron.[26] He was also the first person to conceive the idea of the electron microscope,[27] and submitted the earliest patent for one in 1928.[28] Between 1926 and 1930, he worked with Einstein to develop the Einstein refrigerator, notable because it had no moving parts.[29] He did not build all of these devices, or publish these ideas in scientific journals, and so credit for them often went to others. As a result, Szilard never received the Nobel Prize, but Ernest Lawrence was awarded it for the cyclotron in 1939, and Ernst Ruska for the electron microscope in 1986.[28]

Szilard received German citizenship in 1930, but was already uneasy about the political situation in Europe.[30] When Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933, Szilard urged his family and friends to flee Europe while they still could.[21] He moved to England, and transferred his savings of £1,595 (£120,500 today) from his bank in Zurich to one in London. He lived in hotels where lodging and meals cost about £5.5 a week.[31] For those less fortunate, he helped found the Academic Assistance Council, an organization dedicated to helping refugee scholars find new jobs, and persuaded the Royal Society to provide accommodation for it at Burlington House. He enlisted the help of academics such as Harald Bohr, G. H. Hardy, Archibald Hill and Frederick G. Donnan. By the outbreak of World War II in 1939, it had helped to find places for over 2,500 refugee scholars.[32]

Nuclear physics

On the morning of September 12, 1933, Szilard read an article in The Times summarizing a speech given by Lord Rutherford in which Rutherford rejected the feasibility of using atomic energy for practical purposes. The speech remarked specifically on the recent 1932 work of his students, John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton, in "splitting" lithium into alpha particles, by bombardment with protons from a particle accelerator they had constructed.[33] Rutherford went on to say:

We might in these processes obtain very much more energy than the proton supplied, but on the average we could not expect to obtain energy in this way. It was a very poor and inefficient way of producing energy, and anyone who looked for a source of power in the transformation of the atoms was talking moonshine. But the subject was scientifically interesting because it gave insight into the atoms.[34]

Szilard was so annoyed at Rutherford's dismissal that, on the same day, he conceived of the idea of nuclear chain reaction (analogous to a chemical chain reaction), using recently discovered neutrons. The idea did not use the mechanism of nuclear fission, which was not yet discovered, but Szilard realized that if neutrons could initiate any sort of energy-producing nuclear reaction, such as the one that had occurred in lithium, and could be produced themselves by the same reaction, energy might be obtained with little input, since the reaction would be self-sustaining.[35] He wanted to carry out a systematic survey of all 92 then-known elements in order to find one that can allow the chain reaction, at an estimated cost of $8000, but he did not for lack of funds.[36]

Szilard filed for a patent on the concept of the neutron-induced nuclear chain reaction in June 1934, which was granted in March 1936.[37] Under section 30 of the Patents and Designs Act (1907, UK),[38] Szilard was able to assign the patent to the British Admiralty to ensure its secrecy, which he did.[39] Consequently, his patent was not published until 1949[37] when the relevant parts of the Patents and Designs Act (1907, UK) were repealed by the Patents Act (1949, UK).[40] Richard Rhodes described Szilard's moment of inspiration:

In London, where Southampton Row passes Russell Square, across from the British Museum in Bloomsbury,[41] Leo Szilard waited irritably one gray Depression morning for the stoplight to change. A trace of rain had fallen during the night; Tuesday, September 12, 1933, dawned cool, humid and dull. Drizzling rain would begin again in early afternoon. When Szilard told the story later he never mentioned his destination that morning. He may have had none; he often walked to think. In any case another destination intervened. The stoplight changed to green. Szilard stepped off the curb. As he crossed the street time cracked open before him and he saw a way to the future, death into the world and all our woe,[42] the shape of things to come.[43]

Prior to conceiving the nuclear chain reaction, in 1932 Szilard had read H. G. Wells' The World Set Free, a book describing continuing explosives which Wells termed "atomic bombs"; Szilard wrote in his memoirs the book had made "a very great impression on me."[44] When Szilard assigned his patent to the Admiralty to keep the news from reaching the notice of the wider scientific community, he wrote, "Knowing what this [a chain reaction] would mean—and I knew it because I had read H. G. Wells—I did not want this patent to become public."[44]

In early 1934, Szilard began working at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London. Working with a young physicist on the hospital staff, Thomas A. Chalmers, he began studying radioactive isotopes for medical purposes. It was known that bombarding elements with neutrons could produce either heavier isotopes of an element, or a heavier element, a phenomenon known as the Fermi Effect after its discoverer, the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi. When they bombarded ethyl iodide with neutrons produced by a radon–beryllium source, they found that the heavier radioactive isotopes of iodine separated from the compound. Thus, they had discovered a means of isotope separation. This method became known as the Szilard–Chalmers effect, and was widely used in the preparation of medical isotopes.[45][46][47] He also attempted unsuccessfully to create a nuclear chain reaction using beryllium by bombarding it with X-rays.[48][49]

Manhattan Project

Columbia University

Szilard visited Béla and Rose and her husband Roland (Lorand) Detre, in Switzerland in September 1937. After a rainstorm, he and his siblings spent an afternoon in an unsuccessful attempt to build a prototype collapsible umbrella. One reason for the visit was that he had decided to emigrate to the United States, as he believed that another war in Europe was inevitable and imminent. He reached New York on the liner RMS Franconia on January 2, 1938.[50] Over the next few months, he moved from place to place, conducting research with Maurice Goldhaber at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, and then the University of Chicago, University of Michigan and the University of Rochester, where he undertook experiments with indium but again failed to initiate a chain reaction.[51]

In November 1938, Szilard moved to New York City, taking a room at the King's Crown Hotel near Columbia University. He encountered John R. Dunning, who invited him to speak about his research at an afternoon seminar in January 1939.[51] That month, Niels Bohr brought news to New York of the discovery of nuclear fission in Germany by Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann, and its theoretical explanation by Lise Meitner, and Otto Frisch. When Szilard found out about it on a visit to Wigner at Princeton University, he immediately realized that uranium might be the element capable of sustaining a chain reaction.[52]

Unable to convince Fermi that this was the case, Szilard set out on his own. He obtained permission from the head of the physics department at Columbia, George B. Pegram, to use a laboratory for three months. To fund his experiment, he borrowed $2,000 from a fellow inventor, Benjamin Liebowitz. He wired Frederick Lindemann at Oxford and asked him to send a beryllium cylinder. He persuaded Walter Zinn to become his collaborator and hired Semyon Krewer to investigate processes for manufacturing pure uranium and graphite.[53]

Szilard and Zinn conducted a simple experiment on the seventh floor of Pupin Hall at Columbia, using a radium–beryllium source to bombard uranium with neutrons. Initially nothing registered on the oscilloscope, but then Zinn realized that it was not plugged in. On doing so, they discovered significant neutron multiplication in natural uranium, proving that a chain reaction might be possible.[54] Szilard later described the event: "We turned the switch and saw the flashes. We watched them for a little while and then we switched everything off and went home."[55] He understood the implications and consequences of this discovery, though. "That night, there was very little doubt in my mind that the world was headed for grief".[56]

While they had demonstrated that the fission of uranium produced more neutrons than it consumed, this was still not a chain reaction. Szilard persuaded Fermi and Herbert L. Anderson to try a larger experiment using 500 pounds (230 kg) of uranium. To maximize the chance of fission, they needed a neutron moderator to slow the neutrons down. Hydrogen was a known moderator, so they used water. The results were disappointing. It became apparent that hydrogen slowed neutrons down, but also absorbed them, leaving fewer for the chain reaction. Szilard then suggested Fermi use carbon, in the form of graphite. He felt he would need about 50 tonnes (49 long tons; 55 short tons) (50.8 metric ton) of graphite and 5 tonnes (4.9 long tons; 5.5 short tons) of uranium. As a back-up plan, Szilard also considered where he might find a few tons of heavy water; deuterium would not absorb neutrons like ordinary hydrogen but would have the similar value as a moderator. Such quantities of material would require a lot of money.[57]

Szilard drafted a confidential letter to the President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, explaining the possibility of nuclear weapons, warning of the German nuclear weapon project, and encouraging the development of a program that could result in their creation. With the help of Wigner and Edward Teller, he approached his old friend and collaborator Einstein in August 1939, and persuaded him to sign the letter, lending his fame to the proposal.[58] The Einstein–Szilárd letter resulted in the establishment of research into nuclear fission by the US government, and ultimately to the creation of the Manhattan Project. Roosevelt gave the letter to his aide, Brigadier General Edwin M. "Pa" Watson with the instruction: "Pa, this requires action!"[59]

An Advisory Committee on Uranium was formed under Lyman J. Briggs, a scientist and the director of the National Bureau of Standards. Its first meeting on October 21, 1939, was attended by Szilard, Teller, and Wigner, who persuaded the Army and Navy to provide $6,000 for Szilard to purchase supplies for experiments—in particular, more graphite.[60] A 1940 Army intelligence report on Fermi and Szilard, prepared when the United States had not yet entered World War II, expressed reservations about both. While it contained some errors of fact about Szilard, it correctly noted his dire prediction that Germany would win the war.[61]

Fermi and Szilard met with Herbert G. MacPherson and V. C. Hamister of the National Carbon Company, who manufactured graphite, and Szilard made another important discovery. He asked about impurities in graphite and learned[62] from MacPherson that it usually contained boron, a neutron absorber. He then had special boron-free graphite produced.[63] Had he not done so, they might have concluded, as the German nuclear researchers did, that graphite was unsuitable for use as a neutron moderator.[64] Like the German researchers, Fermi and Szilard still believed that enormous quantities of uranium would be required for an atomic bomb, and therefore concentrated on producing a controlled chain reaction.[65] Fermi determined that a fissioning uranium atom produced 1.73 neutrons on average. It was enough, but a careful design was called for to minimize losses.[66] Szilard worked up various designs for a nuclear reactor. "If the uranium project could have been run on ideas alone," Wigner later remarked, "no one but Leo Szilard would have been needed."[65]

Metallurgical Laboratory

At its December 6, 1941, meeting, the National Defense Research Committee resolved to proceed with an all-out effort to produce atomic bombs. This decision was given urgency by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor the following day that brought the United States into World War II. It was formally approved by Roosevelt in January 1942. Arthur H. Compton from the University of Chicago was appointed head of research and development. Against Szilard's wishes, Compton concentrated all the groups working on reactors and plutonium at the Metallurgical Laboratory of the University of Chicago. Compton laid out an ambitious plan to achieve a chain reaction by January 1943, start manufacturing plutonium in nuclear reactors by January 1944, and produce an atomic bomb by January 1945.[67]

In January 1942, Szilard joined the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago as a research associate, and later the chief physicist.[67] Alvin Weinberg noted that Szilard served as the project "gadfly", asking all the embarrassing questions.[68] Szilard provided important insights. While uranium-238 did not fission readily with slow, moderated neutrons, it might still fission with the fast neutrons produced by fission. This effect was small but crucial.[69] Szilard made suggestions that improved the uranium canning process,[70] and worked with David Gurinsky and Ed Creutz on a method for recovering uranium from its salts.[71]

A vexing question at the time was how a production reactor should be cooled. Taking a conservative view that every possible neutron must be preserved, the majority opinion initially favored cooling with helium, which would absorb very few neutrons. Szilard argued that if this was a concern, then liquid bismuth would be a better choice. He supervised experiments with it, but the practical difficulties turned out to be too great. In the end, Wigner's plan to use ordinary water as a coolant won out.[68] When the coolant issue became too heated, Compton and the director of the Manhattan Project, Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves, Jr., moved to dismiss Szilard, who was still a German citizen, but the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, refused to do so.[72] Szilard was therefore present on December 2, 1942, when the first man-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was achieved in the first nuclear reactor under viewing stands of Stagg Field and shook Fermi's hand.[73]

Szilard started to acquire high-quality graphite and uranium, which were the necessary materials for building a large-scale chain reaction experiment. The success of this demonstration and technological breakthrough at the University of Chicago were partially due to Szilard’s new atomic theories, his uranium lattice design, and the identification and mitigation of a key graphite impurity (boron) through a joint collaboration with graphite suppliers.[74]

Szilard became a naturalized citizen of the United States in March 1943.[75] The Army offered Szilard $25,000 for his inventions before November 1940, when he officially joined the project. He refused.[76] He was the co-holder, with Fermi, of the patent on the nuclear reactor.[77] In the end he sold his patent to the government for reimbursement of his expenses, some $15,416, plus the standard $1 fee.[78] He continued to work with Fermi and Wigner on nuclear reactor design and is credited with coining the term "breeder reactor".[79]

With an enduring passion for the preservation of human life and political freedom, Szilard hoped that the US government would not use nuclear weapons, but that the mere threat of such weapons would force Germany and Japan to surrender. He also worried about the long-term implications of nuclear weapons, predicting that their use by the United States would start a nuclear arms race with the USSR. He drafted the Szilárd petition advocating that the atomic bomb be demonstrated to the enemy, and used only if the enemy did not then surrender. The Interim Committee instead chose to use atomic bombs against cities over the protests of Szilard and other scientists.[80] Afterwards, he lobbied for amendments to the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 that placed nuclear energy under civilian control.[81]

After the war

In 1946, Szilard secured a research professorship at the University of Chicago that allowed him to research in biology and the social sciences. He teamed up with Aaron Novick, a chemist who had worked at the Metallurgical Laboratory during the war. The two men saw biology as a field that had not been explored as much as physics and was ready for scientific breakthroughs. It was a field that Szilard had been working on in 1933 before he had become subsumed in the quest for a nuclear chain reaction.[81] The duo made considerable advances. They invented the chemostat, a device for regulating the growth rate of the microorganisms in a bioreactor,[82][83] and developed methods for measuring the growth rate of bacteria. They discovered feedback inhibition, an important factor in processes such as growth and metabolism.[84] Szilard gave essential advice to Theodore Puck and Philip I. Marcus for their first cloning of a human cell in 1955.[85]

Personal life

Before his relationship with his later wife Gertrud "Trude" Weiss, Leo Szilard's life partner in the period 1927–1934 was the kindergarten teacher and opera singer Gerda Philipsborn, who also worked as a volunteer in a Berlin asylum organization for refugee children and in 1932 moved to India to continue this work.[86] Szilard married Trude Weiss,[87] a physician, in a civil ceremony in New York on October 13, 1951. They had known each other since 1929 and had frequently corresponded and visited each other ever since. Weiss took up a teaching position at the University of Colorado in April 1950, and Szilard began staying with her in Denver for weeks at a time when they had never been together for more than a few days before. Single people living together was frowned upon in the conservative United States at the time and, after they were discovered by one of her students, Szilard began to worry that she might lose her job. Their relationship remained a long-distance one, and they kept news of their marriage quiet. Many of his friends were shocked, having considered Szilard a born bachelor.[88][89]

.jpg.webp)

Writings

In 1949 Szilard wrote a short story titled "My Trial as a War Criminal" in which he imagined himself on trial for crimes against humanity after the United States lost a war with the Soviet Union.[90] He publicly sounded the alarm against the possible development of salted thermonuclear bombs, explaining in a University of Chicago Round Table radio program on February 26, 1950,[91] that sufficiently big thermonuclear bomb rigged with specific but common materials, might annihilate mankind.[92] His comments, as well as those of Hans Bethe, Harrison Brown, and Frederick Seitz (the three other scientists who participated in the program), were attacked by the Atomic Energy Commission's former Chairman David Lilienthal, and the criticisms plus a response from Szilard were published.[91] Time compared Szilard to Chicken Little[93] while the AEC dismissed his ideas, but scientists debated whether it was feasible or not. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists commissioned a study by James R. Arnold, who concluded that it was.[94] Physicist W. H. Clark suggested that a 50 megaton cobalt bomb did have the potential to produce sufficient long-lasting radiation to be a doomsday weapon, in theory,[95] but was of the view that, even then, "enough people might find refuge to wait out the radioactivity and emerge to begin again."[93]

In 1961 he proposed the idea of "Mined Cities", an early example of mutually assured destruction.[96][97]

Szilard published a book of short stories, The Voice of the Dolphins (1961), in which he dealt with the moral and ethical issues raised by the Cold War and his own role in the development of atomic weapons. The title story described an international biology research laboratory in Central Europe. This became reality after a meeting in 1962 with Victor F. Weisskopf, James Watson and John Kendrew.[98] When the European Molecular Biology Laboratory was established, the library was named The Szilard Library and the library stamp features dolphins.[99] Other honors that he received included the Atoms for Peace Award in 1959,[100] and the Humanist of the Year in 1960.[101] A lunar crater on the far side of the Moon was named after him in 1970.[102] The Leo Szilard Lectureship Award, established in 1974, is given in his honor by the American Physical Society.[103]

Cancer diagnosis and treatment

In 1960, Szilard was diagnosed with bladder cancer. He underwent cobalt therapy at New York's Memorial Sloan-Kettering Hospital using a cobalt 60 treatment regimen that his doctors gave him a high degree of control over. A second round of treatment with an increased dose followed in 1962. The higher dose did its job and his cancer never returned.[104]

Last years

Szilard spent his last years as a fellow of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in the La Jolla community of San Diego, California, which he had helped to create.[105] Szilard founded Council for a Livable World in 1962 to deliver "the sweet voice of reason" about nuclear weapons to Congress, the White House, and the American public.[106] He was appointed a non-resident fellow there in July 1963, and became a resident fellow on April 1, 1964, after moving to San Diego in February.[107] With Trude, he lived in a bungalow on the property of the Hotel del Charro. On May 30, 1964, he died there in his sleep of a heart attack; when Trude awoke, she was unable to revive him.[108] His remains were cremated.[109]

His papers are in the library at the University of California, San Diego.[107] In February 2014, the library announced that they received funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission to digitize its collection of his papers, extending from 1938 to 1998.[110]

Patents

- GB 630726—Improvements in or relating to the transmutation of chemical elements—L. Szilard, filed June 28, 1934, issued March 30, 1936

- U.S. Patent 2,708,656—Neutronic reactor—E. Fermi, L. Szilard, filed December 19, 1944, issued May 17, 1955

- U.S. Patent 1,781,541—Einstein Refrigerator—co-developed with Albert Einstein filed in 1926, issued November 11, 1930

Recognition and remembrance

- Atoms for Peace Award, 1959

- Albert Einstein Award, 1960

- American Humanist Association's Humanist of the Year, 1960

- Szilard (crater) on the far side of the Moon, named in 1970

- Leo Szilard Lectureship Award, since 1974

- Asteroid 38442 Szilárd discovered in 1999[111]

- Leószilárdite, mineral, reported in 2016

In media

Szilard was portrayed in the 2023 Christopher Nolan film Oppenheimer by Máté Haumann.[112]

See also

Notes

- Marx, György. "A marslakók legendája". Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 10–13.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 13–15.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, p. 167.

- Byers, Nina. "Fermi and Szilard". Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- Laucht, C. (2012). Elemental Germans: Klaus Fuchs, Rudolf Peierls and the Making of British Nuclear Culture 1939-59. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-137-02833-4. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- Frank 2008, pp. 244–246.

- Blumesberger, Doppelhofer & Mauthe 2002, p. 1355.

- Szilard, Leo (February 1979). "His version of the facts". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 35 (2): 37–40. Bibcode:1979BuAtS..35b..37S. doi:10.1080/00963402.1979.11458587. ISSN 0096-3402. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 36–41.

- Bess 1993, p. 44.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, p. 42.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 44–46.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 44–49.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 49–52.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 56–58.

- Hargittai 2006, p. 44.

- Szilard, Leo (December 1, 1925). "Über die Ausdehnung der phänomenologischen Thermodynamik auf die Schwankungserscheinungen". Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 32 (1): 753–788. Bibcode:1925ZPhy...32..753S. doi:10.1007/BF01331713. ISSN 0044-3328. S2CID 121162622.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 60–61.

- Szilard, Leo (1929). "Über die Entropieverminderung in einem thermodynamischen System bei Eingriffen intelligenter Wesen". Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 53 (11–12): 840–856. Bibcode:1929ZPhy...53..840S. doi:10.1007/BF01341281. ISSN 0044-3328. S2CID 122038206. Available on-line in English at Aurellen.org.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 62–65.

- von Neumann, John (1949). "Review of Norbert Wiener, cybernetics". Physics Today. 2: 33–34.

- Kline, Ronald (2015). The cybernetics moment: Or why we call our age the information age. JHU Press.

- Telegdi, V. L. (2000). "Szilard as Inventor: Accelerators and More". Physics Today. 53 (10): 25–28. Bibcode:2000PhT....53j..25T. doi:10.1063/1.1325189.

- Calaprice & Lipscombe 2005, p. 110.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 101–102.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 83–85.

- Dannen, Gene (February 9, 1998). "Leo Szilard the Inventor: A Slideshow". Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- U.S. Patent 1,781,541

- Fraser 2012, p. 71.

- Rhodes 1986, p. 26.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 119–122.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 131–132.

- Rhodes 1986, p. 27.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 133–135.

- Rotblat, J. (March 1973). "The Sixteen Faces of Leo Szilard". Nature. 242 (5392): 67–68. Bibcode:1973Natur.242...67R. doi:10.1038/242067a0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 4163940.

- GB patent 630726, Leo Szilard, "Improvements in or relating to the transmutation of chemical elements", published 1949-09-28, issued March 30, 1936

- "Section 30: Assignment to Secretary for War or the Admiralty of certain inventions". Patents and Designs Act (1907, UK). The National Archives on behalf of HM Government. Retrieved January 7, 2020 – via legislation.gov.uk.

- Rhodes 1986, pp. 224–225.

- "Changes over time for Section 1". Patents and Designs Act (1907, UK). The National Archives on behalf of HM Government. Retrieved January 7, 2020 – via legislation.gov.uk.

Ss. 1–46 repealed by Patents Act 1949 (c. 87), Schs. 2, 3 and Registered Designs Act 1949 (c. 88), s. 48, Sch. 2

- "Street corner in London where Szilard conceived the idea of the chain reaction", about 1980. Leo Szilard Papers. MSS 32. Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Library.

- Quote from Milton, John (1667) "Paradise Lost", Book I, verse 3

- Rhodes 1986, p. 13.

- "H.G. Wells and the Scientific Imagination". The Virginia Quarterly Review. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- Szilard, L.; Chalmers, T. A. (September 22, 1934). "Chemical Separation of the Radioactive Element from its Bombarded Isotope in the Fermi Effect". Nature. 134 (3386): 462. Bibcode:1934Natur.134..462S. doi:10.1038/134462b0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4129460.

- Szilard, L.; Chalmers, T. A. (September 29, 1934). "Detection of Neutrons Liberated from Beryllium by Gamma Rays: a New Technique for Inducing Radioactivity". Nature. 134 (3387): 494–495. Bibcode:1934Natur.134..494S. doi:10.1038/134494b0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4111335.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 145–148.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, p. 148.

- Brasch, A.; Lange, F.; Waly, A.; Banks, T. E.; Chalmers, T. A.; Szilard, Leo; Hopwood, F. L. (December 8, 1934). "Liberation of Neutrons from Beryllium by X-Rays: Radioactivity Induced by Means of Electron Tubes". Nature. 134 (3397): 880. Bibcode:1934Natur.134..880B. doi:10.1038/134880a0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4106665.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 166–167.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 172–173.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 178–179.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 182–183.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 186–187.

- Rhodes 1986, p. 291.

- Rhodes 1986, p. 292.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 194–195.

- The Atomic Heritage Foundation. "Einstein's Letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt". Archived from the original on June 17, 2022. Retrieved May 26, 2007.

- The Atomic Heritage Foundation. "Pa, this requires action!". Archived from the original on October 29, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2007.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 19–21.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 223–224.

- Weinberg 1994b.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, p. 222.

- Bethe, Hans A. (March 27, 2000). "The German Uranium Project". Physics Today. 53 (7): 34–36. Bibcode:2000PhT....53g..34B. doi:10.1063/1.1292473.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, p. 227.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 28.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 227–231.

- Weinberg 1994a, pp. 22–23.

- Weinberg 1994a, p. 17.

- Weinberg 1994a, p. 36.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 234–235.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 238–242.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 243–245.

- Leo Szilard article of the Atomic Heritage Foundation

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, p. 249.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, p. 253.

- U.S. Patent 2,708,656

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, p. 254.

- Weinberg 1994a, pp. 38–40.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 266–275.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 377–378.

- Grivet, Jean-Philippe (January 1, 2001). "Nonlinear population dynamics in the chemostat" (PDF). Computing in Science and Engineering. 3 (1): 48–55. Bibcode:2001CSE.....3a..48G. doi:10.1109/5992.895187. ISSN 1521-9615. The chemostat was independently invented the same year by Jacques Monod.

- Novick, Aaron; Szilard, Leo (December 15, 1950). "Description of the Chemostat". Science. 112 (2920): 715–716. Bibcode:1950Sci...112..715N. doi:10.1126/science.112.2920.715. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 14787503.

- Hargittai 2006, pp. 143–144.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 395–397.

- Dannen, Gene (January 26, 2015). "Physicist's Lost Love: Leo Szilard and Gerda Philipsborn". dannen.com. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- "Trude Weiss Szilard interviewed by Harold Keen at the Jewish Community Center". 1980.

- Esterer & Esterer 1972, p. 148.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 334–339.

- Jogalekar, Ashutosh (February 18, 2014). "Why the world needs more Leo Szilards". Scientific American. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- Bethe, Hans; Brown, Harrison; Seitz, Frederick; Szilard, Leo (1950). "The Facts About the Hydrogen Bomb". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 6 (4): 106–109. Bibcode:1950BuAtS...6d.106B. doi:10.1080/00963402.1950.11461233.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 317, 366.

- "Science: fy for Doomsday". Time. November 24, 1961. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016.

- Arnold, James R. (1950). "The Hydrogen-Cobalt Bomb". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 6 (10): 290–292. Bibcode:1950BuAtS...6j.290A. doi:10.1080/00963402.1950.11461290.

- Clark, W. H. (1961). "Chemical and Thermonuclear Explosives". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 17 (9): 356–360. Bibcode:1961BuAtS..17i.356C. doi:10.1080/00963402.1961.11454268.

- Szilard, Leo (December 1, 1961). "The Mined Cities". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 17 (10): 407–412. Bibcode:1961BuAtS..17j.407S. doi:10.1080/00963402.1961.11454283. ISSN 0096-3402.

- Horn, Eva (November 1, 2016), Grant, Matthew; Ziemann, Benjamin (eds.), "The apocalyptic fiction: shaping the future in the Cold War", Understanding the Imaginary War, Manchester University Press, pp. 30–50, doi:10.7228/manchester/9781784994402.003.0002, ISBN 978-1-78499-440-2, retrieved September 3, 2023

- "Brief History". European Molecular Biology Laboratory. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- "Szilard Library". European Molecular Biology Laboratory. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- "Guide to Atoms for Peace Awards Records MC.0010". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on August 5, 2015. Retrieved May 19, 2015.

- "The Humanist of the Year". American Humanist Association. Archived from the original on January 14, 2013. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- "Szilard". United States Geographical Survey. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- "Leo Szilard Lectureship Award". American Physical Society. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- Lanouette, William. (2013). Genius in the Shadows : a Biography of Leo Szilard, the Man Behind the Bomb. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-1-62873-477-5. OCLC 857364771.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, pp. 400–401.

- "Founding". Council for a Livable World. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- "Leo Szilard Papers, 1898 – 1998 MSS 0032". University of California in San Diego. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, p. 477.

- Lanouette & Silard 1992, p. 479.

- Davies, Dolores. "Materials Documenting Birth of Nuclear Age to be Digitized". Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- 38442 Szilard (1999 SU6)

- Moss, Molly; Knight, Lewis (July 22, 2023). "Oppenheimer cast: Full list of actors in Christopher Nolan film". Radio Times. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

References

- Bess, Michael (1993). Realism, Utopia, and the Mushroom Cloud: Four Activist Intellectuals and their Strategies for Peace, 1945–1989. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-04421-1. OCLC 27894840.

- Blumesberger, Susanne; Doppelhofer, Michael; Mauthe, Gabriele (2002). Handbuch österreichischer Autorinnen und Autoren jüdischer Herkunft. Vol. 1. Munich: K. G. Saur. ISBN 9783598115455. OCLC 49635343.

- Calaprice, Alice; Lipscombe, Trevor (2005). Albert Einstein: A Biography. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33080-3. OCLC 57208188.

- Esterer, Arnulf K.; Esterer, Luise A. (1972). Prophet of the Atomic Age: Leo Szilard. New York: Julian Messner. ISBN 0-671-32523-X. OCLC 1488166.

- Frank, Tibor (2008). Double exile: migrations of Jewish-Hungarian professionals through Germany to the United States, 1919–1945. Exile Studies. Vol. 7. Oxford: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-03911-331-6. OCLC 299281775.

- Fraser, Gordon (2012). The Quantum Exodus. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-959215-9. OCLC 757930837.

- Hargittai, István (2006). The Martians of Science: Five Physicists Who Changed the Twentieth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517845-6. OCLC 62084304.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Anderson, Oscar E. (1962). The New World, 1939–1946 (PDF). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-07186-7. OCLC 637004643. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- Lanouette, William; Silard, Bela (1992). Genius in the Shadows: A Biography of Leo Szilard: The Man Behind The Bomb. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 1-626-36023-5. OCLC 25508555.

- Rhodes, Richard (1986). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0671441337. OCLC 25508555.

- Weinberg, Alvin (1994a). The First Nuclear Era: The Life and Times of a Technological Fixer. New York: AIP Press. ISBN 1-56396-358-2.

- Weinberg, Alvin (1994b), "Herbert G. MacPherson", Memorial Tributes, vol. 7, National Academy of Engineering Press, pp. 143–147, doi:10.17226/4779, ISBN 978-0-309-05146-0

Further reading

- Szilard, Leo; Weiss-Szilard, Gertrud; Weart, Spencer R. (1978). Leo Szilard: His Version of the Facts – Selected Recollections and Correspondence. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-69070-5. OCLC 4037084.

- Szilard, Leo (1992). The Voice of the Dolphins: And Other Stories (Expanded edition from 1961 original ed.). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1754-0. OCLC 758259818.

External links

- Leo Szilard Online – an "Internet Historic Site" (first created March 30, 1995) maintained by Gene Dannen

- Register of the Leo Szilard Papers, MSS 32, Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Library.

- Leo Szilard Papers, MSS 32, Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Library.

- Lanouette/Szilard Papers, MSS 659, Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Library.

- 2014 Interview with William Lanouette, author of "Genius in the Shadows: A Biography of Leo Szilard, the Man Behind the Bomb." Voices of the Manhattan Project

- Einstein's Letter to President Roosevelt—1939

- The Szilard Library at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory

- Szilard lecture on war

- Einstein and Szilard re-enact their meeting for the film Atomic Power (1946)

- The Many Worlds of Leo Szilard, an invited session sponsored by the APS Forum on the History of Physics at the APS April Meeting 2014, speakers discuss the life and physics Léo Szilárd. Presentations by William Lanouette (The Many Worlds of Léo Szilárd: Physicist, Peacemaker, Provocateur), Richard Garwin (Léo Szilárd in Physics and Information), and Matthew Meselson (Léo Szilárd: Biologist and Peacemaker)

- Leo Szilard on IMDb

- Entry at isfdb.org

- Works by or about Leo Szilard at Internet Archive

- Works by Leo Szilard at Faded Page (Canada)