Leopard Society

The Leopard Society, leopard men, or Anyoto was a secret society that operated in West Africa approximately between 1890 and 1935.[1][2] It was believed that members of the society could transform into leopards through the use of witchcraft.[3] The earliest reference to the society in western literature can be found in George Banbury's "Sierra Leone: or the white man's grave" (1888).[3] In western culture, depictions of the society have been widely used to portray Africans as barbaric and uncivilized.[1]

Members would allegedly dress in leopard skins, waylaying travelers with sharp claw-like weapons in the form of leopards' claws and teeth and engaging in cannibalism, but such allegations have been disputed. Scholar Vicky van Bockhaven writes:

Reports that the Anyoto sometimes imitated leopard attacks, and the existence of their costumes, played on the European imagination. Reports often mention the Anyoto killing innocent victims without any apparent reason. The cannibalistic aspect also receives a great deal of attention in the reports, even if it does not generally seem correct.[1]

Encounters with suspected remnants of the Leopard Society in the post-colonial era have been described by Donald MacIntosh[4] and Beryl Bellman.[5]

In fiction

Fictionalized versions of the Leopard Society feature in the Tarzan novel Tarzan and the Leopard Men, in Willard Price's African Adventure, in Hergé's Tintin au Congo and in Hugo Pratt's Le Etiopiche.

An alternate, more egalitarian version of the Leopard Society appears in the "Nsibidi Script"[6] series by Nnedi Okorafor.[7]

Robert E. Howard also mentions them in his horror/detective short story "Black Talons".

A different take of the Leopard Men appears in The Legend of Tarzan. This version of the group are actually leopards that were magically uplifted by La. A fictional incarnation of the society also appears in the 2016 film The Legend of Tarzan.

In art

.jpg.webp)

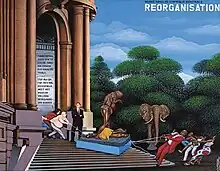

In 1913 the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium, acquired a sculpture by Paul Wissaert commissioned by the Belgium Ministry of Colonies depicting a leopard man preparing to attack a victim.[1] The scene in the sculpture was appropriated by Hergé in Tintin au Congo.[9] The sculpture is depicted by Congolese artist Chéri Samba in Réorganisation (2002), commissioned by the Royal Museum, at the center of a tug-of-war between Africans trying to remove the sculpture from the museum, and whites trying to keep it there.[9][8]

See also

References

- van Bockhaven, Vicky (2009). "Leopard-men of the Congo in literature and popular imagination". Tydskrif vir Letterkunde. 46 (1): 79–94. ISSN 0041-476X.

- "The Leopard Society - Africa in the mid 1900s". Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- Beatty, p.3

- Travels in the White Man's Grave: Memoirs from West and Central Africa, by Donald MacIntosh, 1998

- Beryl L. Bellman (1986). The Language of Secrecy: Symbols and Metaphors in Poro Ritual. Rutgers University Press, p. 47

- "The Nsibidi Scripts".

- @Nnedi (17 November 2018). "Yes, the Leopard Society is real. I didn't make it up in the Akata series. I didn't have to make up a lot of things…" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "The Africa Museum in Brussels". Apollo Magazine. 2019-03-02. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- Wachter, Ellen Mara De (2018-12-11). "Has Belgium's Newly Reopened Africa Museum Exorcized the Ghosts of its Colonial Past?". Frieze. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

Sources

- The International Encyclopedia of Secret Societies & Fraternal Orders, Alan Axelrod, 1997, Checkmark Books

- Pratten, David (2007). The Man-Leopard Murders: History and Society in Colonial Nigeria. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34956-9.

- Poore Sheehan, Perley (2007). The Leopard Man and Other Stories. Pulpville Press. ISBN 978-1-936-72002-6.

- Beatty, K.J. (1915). Human Leopards. London: Hugh Rees Ltd.

- Aye, Efiong U. (1991). A learner's dictionary of the Efik Language, Volume 1. Ibadan: Evans Brothers Ltd. ISBN 9781675276.

External links

- The Leopard Society in the Nimba Range and at the Kru coast Archived 2012-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- 1900-1950: The Leopard Society in 'Vai country' in Bassaland Archived 2010-11-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Human Leopards: An account of the trials of human leopards before the special commission court: With a note on Sierra Leone, Past and present