Les Télots Mine

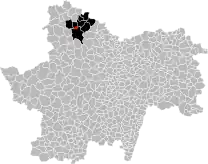

Les Télots Mine extracted oil shale dating from the Asselian era at Saint-Forgeot, on the outskirts of Autun in Saône-et-Loire town in central-eastern France.

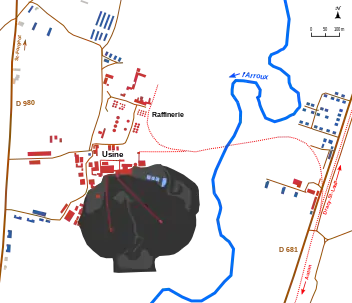

In the foreground, is a workers' company town. Behind, the distillation plant, the refinery, and the two conical slag heaps. | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

Les Télots Mine | |

| Location | Saint-Forgeot commune, Saône-et-Loire department, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region. |

| Country | France |

| Coordinates | 46°59′12″N 04°18′12″E |

| Production | |

| Type | Autun oil shale deposit |

| History | |

| Opened | April 22nd, 1865. |

| Active | 1865-1881: Télots concession,

1881-1936: SLSB (Société lyonnaise des schistes bitumineux), 1936-1957: SMSB (Société Minière des Schistes Bitumineux) |

| Closed | August 31st, 1957. |

Shale mining in the area began in 1824 at Igornay. By 1837, shale oil was being produced for public lighting, and installations were constantly being improved to diversify production. Les Télots concession was granted in 1865. The refinery completed the oil distillation plant in 1936, employing several hundred workers who produced automotive fuel. During the Occupation, the site was of strategic importance to the German army, which kept a watchful eye on it, and minor acts of sabotage were carried out by the local resistance and the Allies (notably the Scullion raids). In retaliation, militiamen executed five workers.

Following closure in 1957, the site was dismantled and partially demolished. Remains of the installations (ruins) and two large spoil tips still mark the landscape at the beginning of the 21st century, overgrown with particular vegetation studied for its biodiversity. Les Télots is recognized as a natural zone of ecological, faunistic, and floristic interest (ZNIEFF).

Location

The mine is located in a Morvan valley in the commune of Saint-Forgeot, on the outskirts of Autun in the north of the Saône-et-Loire département, in the Burgundy-Franche-Comté region of eastern France.[1]

Geology

The Autun oil shale deposit gives its name to the geological period in which it was formed: the Autunian, from 299 to 282 million years ago,[2] with a thickness of 1.3 km. The oil shale layers are interspersed with fine detrital sediments, including limestone. The layers form lenses of widely varying thickness and quality. The deposit is underlain by the Stéphanien d'Épinac coal bedrock.[3]

The basin is divided into two strata, themselves subdivided into two beds. Les Télots Mine exploits a deposit belonging to the Upper Autunian and Millery strata, which are 250 meters thick of shale, crossed by clastic rock. It has ten bituminous layers, the top of which is composed of torbanite, a type of bituminous coal.[4]

In the early 1980s, studies conducted by Pascal Martaud for BRGM revealed significant reserves[5] (20 to 30 million tonnes). The deposit covers an area of 240 km2.[6]

History

General information

The deposit was discovered in 1813 in Igornay, and extraction began in 1824. From 1837 onwards, shale oil was produced industrially for street lighting in major cities such as Paris, Lyon, Dijon, and Strasbourg.[7][8][9][10] The shale is crushed and heated to between 450°C and 500°C in a confined, airless space. The gas that escapes is then condensed to obtain a liquid material similar to petroleum.[11] In 1847, Autun's lamp oil was confronted with competition from coal gas, but production soon began to rise again.[6]

By the late 19th century, shale was being extracted up to 300 meters underground, shareholders were making a 30% profit, and production peaked in 1864 and 1865 (6,700 tons of oil extracted from oil shale in 1865[12]). However, with the arrival of competition from American and Russian oil in 1870, several concessions disappeared. In 1881, the Société lyonnaise des schistes bitumineux (SLSB) bought out several remaining concessions to revive production. With new private capital and government support, it obtained a monopoly in 1891. Between 1840 and 1870, the surface installations were gradually extended, notably to produce oil, paraffin, sulfates, and ammonia. The latter products were abandoned after World War I.[6][7][8][9][13]

In 1892, the French government reduced taxes on foreign petroleum products, making them more competitive with Autun shale oil. To compensate for this, bonuses were introduced, which enabled the facilities to be modernized, increasing the yield of crude oil by 30%. Following the 1914 mobilization, the Ravelon (Dracy-Saint-Loup) and Margenne (Monthelon) mines and plants were forced to close. Mining was concentrated at Télots and Surmoulin (Dracy-Saint-Loup). In 1933, a law allowed tax exemption for gasolines derived from shale oil, opening up new prospects. Nonetheless, social reforms introduced by the Front Populaire in 1936 reduced SLSB's profitability. In response, a new company, Société Minière des Schistes Bitumineux (SMSB), was created with financial backing from Pechelbronn SAEM.[14]

Les Télots

The 126-hectare Télots concession was granted on April 22, 1865.[15] The mining and processing facilities were developed by SLSB after 1881. In 1911, the French equipment was replaced by a Scottish system, including more efficient Pumpherston retorts.[8]

A refinery with cracking units was opened in 1936 to complement the oil distillation plant, and the company specialized in automotive fuels. Following a change of ownership, the company changed its name to Société minière des schistes bitumineux (SMSB).[8][10] The workforce numbered 600, including around 100 miners, who extracted almost 1,000 tonnes of shale daily, producing 70 million liters of gasoline a year.[13]

During the Second World War Occupation, 600 workers were employed at Les Télots, including former miners from the Épinac collieries. There was also a population of Polish origin, living mainly in the workers' company houses.[16] Equipment was recovered from the Eugène Soyez shaft at Sincey collieries in Côte-d'Or for use at Les Télots.[17] The pyrogenation facilities were strategic for the German army, which obtained its fuel supplies there. The area was guarded by the Luftwaffe and militiamen from Autun. Acts of sabotage (including arson) were first carried out by the French army during the 1940 debacle. Two missions, known as "Scullion 1 and 2", were carried out by the Special Air Service (SAS),[16] notably by SOE agents George Connerade, George Demand, George Larcher, Eugène Levene, Jack Hayes, Jean Le Harivel, David Sibree, and Victor Soskice.[18] Other actions were carried out by the local resistance (maquis Socrate). But each of these attacks inflicted only minor damage on the facilities. In retaliation, militiamen executed young workers aged between 17 and 20: three Frenchmen and a Polish man, as well as the latter's father. Following the Liberation, the fuel was used by the First French Army.[9][19]

On April 1, 1944, the Saint-Léger-du-Bois and Moloy coal concessions in Épinac were taken over by Les Télots mines, which needed fuel.[10] By the 1950s, production had risen to 22,000 tonnes of processed products, despite a gradual reduction in the workforce,[20] thanks to the use of roadheaders, excavators, and conveyor belts, which changed the mining method and replaced pillar mining. This method enabled 95% of the layers visited to be recovered, compared with a maximum of 60% before World War II.[8] Production ceased on August 31, 1957, due to competition from liquid oil, which was easier to extract, although 340 workers were still employed.[9][11]

Les Télots well, c. 1880.

Les Télots well, c. 1880. The extraction shaft c. 1900.

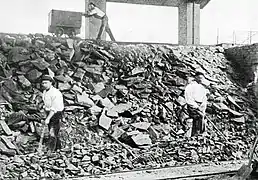

The extraction shaft c. 1900. Shale preparation.

Shale preparation. Crushing and stockpiling.

Crushing and stockpiling.

Staff

The workforce was mainly made up of local farmers; Polish miners were recruited in the early 1930s. The maximum number of employees was 1,420. Wages were lower than at Épinac Collieries. Bottom miners worked 46 hours 30 min a week, while surface workers worked between 44 and 48 hours a week, depending on the position. Les Télots mine did not suffer any major mining disasters, although a dozen miners died in technical accidents between 1914 and 1957. From 1872 onwards, a union chamber was responsible for the social welfare of the workers at Les Télots. It was replaced by a relief society in 1936. In 1946, the miners' status was identical to that of the Charbonnages de France.[8]

Post-mining

Reconversion

Electricité de France (EDF)[8] was responsible for the reconversion. After closure, the mine entrances were backfilled, the installations dismantled and largely demolished by the Pigeat company. A Dubbs cracking unit was dismantled and reassembled at the Pechelbronn site in Alsace.[16]

Vestiges

The ruins of maintenance buildings, the crushing-storage building, two water towers, and a factory chimney were still standing at the beginning of the 21st century, overgrown by vegetation, as were the two large spoil tips,[10][11][21] reaching heights of 386 and 397 meters, i.e. a hundred meters higher than the plain, thus marking the landscape.[16][22]

- Surface remains.

Aerial overview.

Aerial overview. Perspective, chimney, two water towers and two slag heaps.

Perspective, chimney, two water towers and two slag heaps. Old railway access.

Old railway access. Crusher building seen from the slope tips.

Crusher building seen from the slope tips.

Closed water tower.

Closed water tower. Inside view.

Inside view. Open water tower.

Open water tower. Base of the chimney.

Base of the chimney. Full fireplace.

Full fireplace. Crushers.

Crushers. Crusher building (on the downhill side).

Crusher building (on the downhill side). Downhill view of machinery.

Downhill view of machinery.

- The two conical spoil tips.

Ground view.

Ground view. Aerial view.

Aerial view. Gradient view.

Gradient view. The summit.

The summit.

Biodiversity

Biodiversity is studied by naturalists, particularly for its butterflies, amphibians and flora. Since 2007, the Autun Natural History Museum has been showcasing this industrial and natural heritage with exhibitions.[23]

Les Télots is recognized as a natural zone of ecological, faunistic, and floristic interest (ZNIEFF). From a sterile, stony soil, several types of natural areas have developed: siliceous scree, various types of low-acid silicolous lawns with annual plants, thin hay meadows colonized by Arrhenatherum elatius, aquatic vegetation such as the broad-leaved pondweed (Potamogeton natans), which develops in mining subsidence reservoirs.[24]

Inclined spoil tips are colonized by a birch grove, while the flat industrial wasteland is occupied by an oak-ash forest. Wetlands include both reed beds with Phragmites and Typha, and wet meadows with Yellow Rush (Juncus inflexus). More than 210 plant species have been inventoried, the most notable are the mourning sorrel (Rumex thyrsiflorus), the bean-leaved sedum (Hylotelephium telephium), the rosemary fireweed (Epilobe de feuilles de romarin) and the white cephalanthera (Cephalanthera damasonium). The presence of ponds provides shelter for amphibians, notably the green tree frog (Hyla arborea), a protected species.[25]

- Most notable species recorded.

References

- J. Le Goff 2013, p. 9.

- Georges Gand 2010.

- J. Le Goff 2013, p. 11.

- J. Le Goff 2013, p. 12.

- Jean-Philippe Passaqui et Sylvain Bellenfant 2010, p. 9.

- Recherches des étudiants, Gilles Miot, "L'exploitation de schiste bitumineux dans l'Autunois : La mine et l'usine des Télots" archive [PDF].

- R.Feys 1945, p. 16-17.

- Bernard Lecomte, La Bourgogne Pour les Nuls, EDI8, June 20th, 2013 (ISBN 9782754054874, read online archive), Deux mystérieux terrils à l'entrée d'Autun....

- CCCA after Gilles Pacaud, "What future for oil shale?", on gensdumorvan.fr archive.

- "Les Houillères de Blanzy en Bourgogne : Mine de schiste bitumineux des Télots - Autun / Saint-Forgeot" archive, on patrimoine-minier.fr archive.

- "Les Houillères de Blanzy : Mine des Télots" archive, on exxplore.fr archive.

- Lucien Taupenot, "Quand le pétrole autunois éclairait Paris, Lyon, Dijon, Strasbourg", Images de Saône-et-Loire, no. 145, March 2006, pp. 2 and 3.

- Lilian Bonnard, "Gaz de schiste et si on rouvrait la mine d'Autun?", on miroir-mag.fr archive, October 14th, 2013.

- J. Le Goff 2013, p. 17.

- R.Feys 1945, p. 20-21.

- Jean-Philippe Passaqui et Sylvain Bellenfant 2010, p. 5.

- [PDF] Jean-Philippe Passaqui, Mines et minières de Côte-d'Or au XIXe siècle, 2001 (read online archive), p. 394.

- Michael R D Foot, Jean-Louis Crémieux-Brilhac, Des anglais dans la résistance. Le SOE en France, 1940-1944, Tallandier, 2013, 831 p. (ISBN 979-10-210-0194-7, read online archive).

- "July 20th, 1944 at Télots, murder of the Warzyboks" archive, on respol71.com archive.

- Jean-Philippe Passaqui et Sylvain Bellenfant 2010, p. 4-5.

- J. Le Goff 2013 (4), p. 9 (Annex 7).

- "IGN map of slope tips archive" on Géoportail.

- Jean-Philippe Passaqui et Sylvain Bellenfant 2010, p. 5-7.

- S.H.N.A. (Bellenfant S., Balay G.) 2016, p. 2-3.

- S.H.N.A. (Bellenfant S., Balay G.) 2016, p. 2-3.

See also

Related articles

External links

- [video] Autun : à la découverte de l'ancienne mine des Télots archive on YouTube by France 3 Bourgogne-Franche-Comté.

- "Histoire des mines de schiste" archive, on mairie-saint-forgeot.fr archive

- ZNIEFF 260030145 - Les Télots à Saint-Forgeot [archive], INPN website.

Bibliography

- [PDF] R. Feys, Puits et sondage dans le bassin d'Autun et Epinac, des origines à nos jours, BRGM, October 15, 1945 (read online archive).

- Dominique Chabard et Jean-Philippe Passaqui, L'essence autunoise, un carburant national : Patrimoine industriel, scientifique et technique, Autun, Muséum d'histoire naturelle d'Autun, 2006, 99 p.

- Jean-Philippe Passaqui et Dominique Chabard, Les routes de l'énergie : Epinac, Autun, Morvan, Muséum d'histoire naturelle d'Autun, 2007.

- [PDF] Jean-Philippe Passaqui et Sylvain Bellenfant, Les Télots : une usine devenue friche industrielle aux portes d’Autun, Bourgogne-Nature, December 2010 (read online).

- [PDF] Georges Gand, Reprise de fouilles paléontologiques dans un gîte bourguignon célèbre : les «schistes bitumineux» de l’Autunien de Muse (Bassin d’Autun): Bilan 2010 et perspectives, Bourgogne-Nature, December 2010 (read online).

- [PDF] J. Le Goff, Étude des aléas miniers dans le bassin d'Autun, Bourgogne (71) (exploitations de houille, schistes bitumineux et fluorine): Communes de Autun, Barnay, Cordesse, Curgy, Dracy-Saint-Loup, Igornay, La Celle en Morvan, Monthelon, La Grande Verrière, La Petite Verrière, Reclesne, Saint Forgeot, Saint Léger du Bois, Sully et Tavernay, vol. 1, Géoderis, February 21, 2013 (read online archive).

- [PDF] S.H.N.A. (Bellenfant S., Balay G.), Les Télots à Saint-Forgeot, INPN, 2016 (read online archive).

- [PDF] J. Le Goff, Étude des aléas miniers dans le bassin d'Autun, Bourgogne (71) (exploitations de houille, schistes bitumineux et fluorine) : Communes de Autun, Barnay, Cordesse, Curgy, Dracy-Saint-Loup, Igornay, La Celle en Morvan, Monthelon, La Grande Verrière, La Petite Verrière, Reclesne, Saint Forgeot, Saint Léger du Bois, Sully et Tavernay, vol. 4, Géoderis, 2013 (4) (read online archive).