Leslie Lynch King Sr.

Leslie Lynch King Sr. (July 25, 1884 – February 18, 1941) was the biological father of U.S. President Gerald Ford. Because of his alcoholism and abusive behavior, his wife, Dorothy Gardner, left him sixteen days after Ford's birth.

Leslie Lynch King Sr. | |

|---|---|

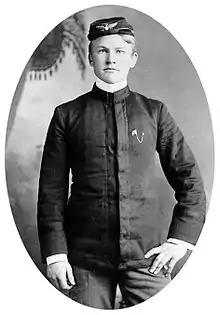

Leslie Lynch King Sr., circa 1900 | |

| Born | Leslie Lynch King July 25, 1884 Chadron, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Died | February 18, 1941 (aged 56) Tucson, Arizona, U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California, U.S. |

| Known for | Biological father of Gerald Ford |

| Spouses | |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

Personal life

King was born in Chadron, Nebraska, the son of businessman Charles Henry King and Martha Alicia (née Porter) King. King attended military academy in Missouri.[2] His father founded several small trading towns in Nebraska and Wyoming along the railroad. He also became a banker and was very successful. In 1905, the family moved to Omaha, Nebraska, where his parents commissioned the construction of a large Victorian mansion.

In May 1908, King, his father, Dana C. Bradford and H. C. Brome incorporated the Omaha Wool and Storage company,[3] a business King would later take over.[2] King was prone to violence,[4] and in November 1908 he and his father were indicted for beating one of their employees.[5][6] King's father later took a primary house in Los Angeles and since the company's business interests were largely in Wyoming, the younger King became the primary manager. King later took a residence in Los Angeles as well.[2]

Marriage and family

First marriage

While one of his sisters, Marietta, was at Wellesley College in Wellesley, Massachusetts, King met and courted her roommate, Dorothy Ayer Gardner of Harvard, Illinois. They were married on September 7, 1912 at Christ Episcopal Church. Dorothy and King returned to Omaha where King was working.[7] King was eight years older than his wife.[8] When they returned to Omaha, Dorothy discovered that King was not as wealthy as he claimed; in fact, he was deep in debt.[9] On their honeymoon to the West Coast and then in Omaha, King abused his wife, and eventually threw her out. Dorothy returned to her parents' home in Illinois, and a few weeks later Leslie came to their home and Dorothy agreed to return to Omaha with him.[8]

They initially lived with his parents at 3202 Woolworth in the Hanscom Park neighborhood, a central part of the city. After returning from Illinois, however, they moved into a basement apartment.[8] Their son, Leslie Jr., was born on July 14, 1913. Dorothy had quickly learned that King was abusive, short-tempered and had trouble with alcohol. A few days after their son's birth, King gestured at his wife and son with a butcher knife and threatened to kill them. Dorothy quickly completed plans to leave her husband; she would not tolerate the abuse, or the threats to their son's safety.[10][9] King also quarreled with his mother-in-law.

Sixteen days after the birth, Dorothy Gardner King left Omaha with her son for Oak Park, Illinois, home of her sister Tannisse and brother-in-law Clarence Haskins James. From there, she moved to the home of her parents Levi Addison Gardner and Adele Augusta (née Ayer) in Grand Rapids, Michigan.[1] On December 19, 1913, an Omaha court granted a divorce to the Kings. Leslie King refused to pay child support, and the court found that he had no money and no job. King's father had recently fired him for mismanaging a warehouse, overdrawing his bank account, and poor personal conduct.[11] In 1916, Charles H. King agreed to pay the delinquent alimony and future child support until his death on the stipulation that Dorothy drop charges against Leslie.[12]

On February 1, 1917, Dorothy Gardner King married Grand Rapids businessman Gerald Rudolff Ford. They called her son Gerald Ford Jr., although he was not formally adopted. In honor of his stepfather, in 1935 at the age of 22, young Gerald legally changed his name to Gerald Rudolph Ford, adopting the more-common spelling of his middle name. The Fords also had three sons together.

Second marriage

King married Margaret Atwood in Reno, Nevada, in 1919. They had three children:

Later years and death

Gerald Ford's mother and stepfather did not tell him of his biological father until shortly before he turned fifteen, in 1928. Ford described his biological father as "a carefree, well-to-do man who didn't really give a damn about the hopes and dreams of his firstborn son".[13][14] Ford's paternal grandfather, Charles Henry King, took care of his first grandson and paid Ford's mother child support until shortly before his death in 1930. After Charles' death, Leslie inherited $50,000 ($687,000 in 2016 dollars), and Dorothy got a judgment from Nebraska courts to force him to pay support. King was living in Wyoming, outside of Nebraska's legal jurisdiction, and refused.[15]

King met his firstborn son for the first time when Ford was a sophomore in high school. King came to Michigan to pick up a new car and visited Ford where the future president was working at a restaurant in Grand Rapids.[8] They had a superficial conversation. King, who had never paid child support, handed Ford $25. It is believed that the two had no further contact,[16][17][18] although it is also reported that Ford visited King Sr. one summer at King's spacious home in Wyoming when Ford was working at Yellowstone,[8] and that King once visited his son at Yale when Ford was assistant football coach there.[15]

In 1939, King moved from his home in Riverton, Wyoming, to Lincoln, Nebraska. In Nebraska, he was arrested for failing to pay alimony, particularly what was due after the death of King's father in 1930.[19]

King died on February 18, 1941, in Tucson, Arizona.[2][8] He was buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, in Glendale, California, near his parents.[15] In 1949, his widow Margaret King married Roy Mather.

References

- "University of Texas Ford Genealogy". Archived from the original on December 23, 2006.

- "Youth Told 'You're my Son'". News Journal. Mansfield, Ohio (originally in the Los Angeles Times). August 14, 1974. p. 3. Archived from the original on 2017-02-21. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- "Wool Company is Incorporated". The Kearney Daily Hub. Kearney, Nebraska. May 19, 1908. p. 1. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "Mrs. King Tells Hers Story". Omaha Daily Bee. Omaha, Nebraska. October 21, 1913. p. 8. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- "Claims Kings Beat Him". Omaha Daily Bee. Omaha, Nebraska. November 22, 1908. p. 5. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "List of Indictments found". Omaha Daily Bee. Omaha, Nebraska. December 5, 1908. p. 8. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- Cannon & Cannon 2013, p. 40

- Gullan 2004

- Cannon & Cannon 2013, p. 41

- James M. Cannon (1995). "Gerald R. Ford". In Wilson, Robert A. (ed.). Character Above All: Ten Presidents from FDR to George Bush. Retrieved August 21, 2009 – via PBS.

- Cannon & Cannon 2013, p. 42

- "Father Has Agreed to Pay Son's Alimony". Omaha World Herald. Omaha, Nebraska. October 19, 1916. p. 1.

- Ford, Gerald (1979). A Time to Heal: The Autobiography of Gerald R. Ford. Harper & Row. p. 48. ISBN 9780060112974.

- Holmes 2012, p. 125

- Young 1997

- "Nebraska-born, Ford Left State as Infant". The Associated Press, The New York Times. December 27, 2006..

- Cannon & Cannon 2013, pp. 46–47 (Cannon reports it as $20)

- Holmes 2012, p. 124

- "Say King Failed to Pay Alimony". The Lincoln Star. Lincoln, Nebraska. May 5, 1939. p. 15. Archived from the original on 2017-02-21. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

Sources

- Gullan, Harold I. (2004). First Fathers: The men who inspired our presidents. Wiley. pp. 241–243.

- Holmes, David L. (2012). The Faiths of the Postwar Presidents: From Truman to Obama. Vol. 5. University of Georgia Press. p. 124 – via Project MUSE.

- Cannon, James; Cannon, Scott (2013). Gerald R. Ford: An Honorable Life. University of Michigan Press – via Project MUSE.

- Wead, Doug (2005). The Raising of a President: The Mothers and Fathers of Our Nation's Leaders. Simon and Schuster. pp. 400–401.

- Young, Jeff C. (1997). The Fathers of American Presidents: From Augustine Washington to William Blythe and Roger Clinton. McFarland & Company. pp. 205–207.