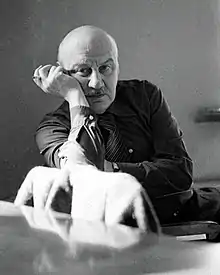

Lev Kulidzhanov

Lev Aleksandrovich Kulidzhanov (Russian: Лев Александрович Кулиджанов; 19 March 1924 – 17 February 2002) was a Soviet and Armenian film director, screenwriter and professor at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography. He was the head of the Union of Cinematographers of the USSR (1965—1986). People's Artist of the USSR (1976). He directed a total of twelve films between 1955 and 1994.[1]

Lev Kulidzhanov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Lev Aleksandrovich Kulidzhanov 19 March 1924 |

| Died | 17 February 2002 (aged 77) |

| Occupation(s) | Film director, screenwriter, pedagogue |

| Years active | 1955–1994 |

Biography

Born on 19 March 1924 (according to other sources including his tomb — on 19 August 1923[2]) in Tiflis, Transcaucasian SFSR. His father Aleksandr Nikolayevich Kulidzhanov (originally Kulidzhanyan) was an Armenian revolutionary who served as a high-ranking Communist Party official. He was arrested during the Great Purge of 1937 and disappeared without a trace. Kulidzhanov's mother Yekaterina Dmitriyevna was either of Russian[3] or of Armenian descent.[4] She was arrested along with her husband and sentenced to five years in the Akmol labor camp in Kazakhstan. She returned home only in 1944. All those years Kulidzhanov spent with his grandmother Tamara Nikolaevna.[5]

From 1942 to 1943 he studied at the Tbilisi State University. In 1944 he traveled to Moscow and enrolled in the All-Union State Institute of Cinematography to study film direction under Grigori Kozintsev, but left it in just a year because of the poor living conditions and returned to Tbilisi. In 1948 Kulidzhanov became a VGIK student again, with Sergei Gerasimov and Tamara Makarova as his teachers. He graduated in 1955 and immediately started working at the Gorky Film Studio, releasing his first short film Ladies co-directed with Genrikh Oganisyan.

His first success happened with a movie The House I Live In co-directed with Yakov Segel. It became one of the 1957 Soviet box office leaders, reaching the 9th place with 28.9 million viewers.[6] Not only it was the first cinema role of the acclaimed Russian actress Zhanna Bolotova, but Kulidzhanov himself also played one of the characters. It was his only big screen role in the entire career. His next film A Home for Tanya turned to be another success and competed for the Palme d'Or at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival.[7]

But his real breakthrough happened with the 1961 drama film When the Trees Were Tall that introduced such actors as Yuri Nikulin, Inna Gulaya, Lyudmila Chursina and Leonid Kuravlyov in their first serious roles. While not as successful with Soviet viewers at the time of release, it turned into a cult classic with years. In 1962 it was also selected for the 1962 Cannes Film Festival.[8] In 1969 Kulidzhanov directed the first Soviet adaptation of the Crime and Punishment novel with many acclaimed Soviet actors involved. Although it failed at the box office and left some of his colleagues unimpressed (like Andrei Tarkovsky who also dreamed of adapting the novel[9]), it was praised by critics and intelligentsia. The movie was officially selected for the 31st Venice International Film Festival, and the filming crew was awarded with the Vasilyev Brothers State Prize of the RSFSR in 1971.[10]

In 1965 Kulidzhanov was elected as the head of the Union of Cinematographers of the USSR, substituting Ivan Pyryev at this post. As the head of the Union he helped to preserve a lot of films, founded the Cinema Museum and saved the archive of Sergei Eisenstein. He held this position for 20 years straight, up till the scandalous 5th Congress of the Soviet Filmmakers in 1986 when a group of activists (presumably encouraged by Alexander Yakovlev[11][12]) started booing the lecturers, accusing Kulidzhanov and other leading directors of «nepotism» and «political conformism» and demanding a reelection of the whole board. All this led to a split, restructuring and a quick demise of the Soviet cinema.

After Kulidzhanov left the Union, he wasn't able to direct anything up until the 1990s when he made his two final films. Both of them symbolized a return to his earlier days of film making and were written by his wife Natalia Anatolyevna Fokina (born 1927), a professional screenwriter whom he met during the 1940s. They had two sons: Aleksandr (born 1950, died 2018), a cinematographer, and Sergei (born 1957), a historian.

Kulidzhanov died on 17 February 2002 and was buried in Moscow at the Kuntsevo Cemetery.[2]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Original title | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Director | Screenwriter | Notes | |||

| 1955 | Ladies | Дамы | Co-directed with Genrikh Oganisyan | ||

| 1956 | That's How It Started... | Это начиналось так… | Co-directed with Yakov Segel | ||

| 1957 | The House I Live In | Дом, в котором я живу | Actor (Vadim Volynsky); co-directed with Yakov Segel | ||

| 1959 | A Home for Tanya | Отчий дом | |||

| 1960 | The Lost Photo | Потерянная фотография | Joined USSR-ČSSR production | ||

| 1961 | When the Trees Were Tall | Когда деревья были большими | |||

| 1962 | Fitil №5 | Co-directed with Isaak Magiton | |||

| 1963 | The Blue Notebook | Синяя тетрадь | |||

| 1969 | Crime and Punishment | Преступление и наказание | |||

| 1972-1974 | Starlit Minute | Звёздная минута | Co-directed with Artavazd Peleshyan | ||

| 1980 | Karl Marx: The Early Years | Карл Маркс. Молодые годы | Joined USSR-GDR production | ||

| 1987 | Risk | Риск | Joined USSR-Japan-ČSSR-West Germany production | ||

| 1991 | Not Afraid to Die | Умирать не страшно | |||

| 1994 | Forget-me-nots | Незабудки |

Awards and honors

- People's Artist of the RSFSR (1969)

- Vasilyev Brothers State Prize of the RSFSR (1971) – for the film Crime and Punishment (1969)

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1974)

- People's Artist of the USSR (1976)

- Lenin Prize (1982)

- Hero of Socialist Labour (1984)

- Two Orders of Lenin

- Order "For Merit to the Fatherland", 3rd class (1999) – for an outstanding contribution to cinema and at his 75th birthday

References

- Peter Rollberg (2009). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. US: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 383–385. ISBN 978-0-8108-6072-8.

- Celebrity Tombs

- Lists of Victims of Red Terror in the USSR. Kulidzhanova Ekaterina Dmitrievna (in Russian)

- Maria Tokmadzhyan.Soviet Neoromantic at the Golos Armenii newspaper, 20 August 2014 (in Russian)

- Lev Kulidzhanov. Mastering Profession by Natalia Fokinam, fragments of her book in the Notes on Film Study journal by the Eisenstein-Centre, 2003 (in Russian)

- The House I Live In at KinoPoisk

- Official Selection 1959 : All the Selection at the Cannes Film Festival official website

- Official Selection 1962 : All the Selection at the Cannes Film Festival official website

- Time Within Time: The Diaries 1970–1986

- Crime and Punishment Archived 16 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine at the National Cinema Encyclopedia, project of the Seance film study journal

- Natalya Bondarchuk (2010). Sole Days. Moscow: AST, 368 p. ISBN 978-5-17-062587-1

- Feodor Razzakov (2013). Industry of Betrayal, or Cinema That Blew Up the USSR. Moscow: Algorithm, 416 p. ISBN 978-5-4438-0307-4

Literature

- Margarita Kvasnetskaya (1968). Lev Kulidzhanov. Moscow: Iskusstvo, 120 pages.

- Natalia Fokina (2004). Back Then the Trees Were Tall. Lev Kulidzhanov in his Wife's Memories. Yekaterinburg: U-Fakrotia, 292 pages.

- Natalia Fokina. When the Trees were Tall. Dedicated to Lev Kulidzhanov. Part 1. // The Art of Cinema journal, № 11, 2003 (in Russian)

- Natalia Fokina. When the Trees were Tall. Dedicated to Lev Kulidzhanov. Part 2. // The Art of Cinema journal, № 12, 2003 (in Russian)

External links

- Lev Kulidzhanov at IMDb

- The Observer. 90 years since Kulidzhanov was born talk-show by Russia-K