Lewis H. Michaux

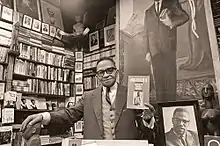

Lewis H. Michaux (1885/1895 – 1976) was a Harlem bookseller and civil rights activist. Between 1932 and 1974 he owned the African National Memorial Bookstore in Harlem, New York City, one of the most prominent African-American bookstores in the country.

Lewis H. Michaux | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1885 or 1895 Newport News, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | August 25, 1976 (aged 92 or 82) |

| Occupation | Bookseller |

| Known for | African National Memorial Bookstore |

| Relatives | Lightfoot Solomon Michaux (brother) |

Biography

Michaux was born in Newport News, Virginia, 1895 — although his birth year and day is uncertain; according to The New York Times he was born August 4, 1885[1] — the son of Henry Michaux and Blanche Pollard. Michaux had little formal education.

Before coming to New York he worked as a pea picker, window washer and deacon in the Philadelphia church of his brother, Lightfoot Solomon.

Michaux died of cancer at Calvary Hospital in the Bronx, New York. He was reportedly 92 at the time of his death.[1]

Personal life

Michaux was married to Bettie Kennedy Logan and they had one son. His brother, Solomon Lightfoot Michaux, acted as an advisor for U.S. President Harry S. Truman and helped to build a 500+ unit housing development for the poor.[2]

African National Memorial Bookstore

The bookstore was founded by Michaux in 1932 on 7th Avenue and stayed there until 1968, when Michaux was forced to move the store to West 125th Street (on the corner of 7th avenue) to give space to the State Harlem office building. The bookstore finally closed in 1974 after another row with authorities over its location.[3]

Michaux stimulated a generation of students, intellectuals, writers and artists.[4] He called his bookstore "House of Common Sense and the Home of Proper Propaganda". The store became an important reading room of the Civil Rights Movement.[5] While Izzy Young's Folk Center further south in Greenwich Village became a hang-out during the folk revival of the late 1950s and early 1960s, including the rising Bob Dylan,[6][7] the Memorial Bookstore up in Harlem was a rare place for black people and scholars and anyone interested in literature by, or about, African Americans, Africans, Caribbeans and South Americans. In the early 1960s folk and popular music, and the civil rights movement, were inter-related, overlapping and "inspiring the growth and creativity of each other" as historians Izzerman and Kazin write[8] Michaux's bookstore had over 200,000 texts and was the nation's largest on its subject.[9] Everyone, white and black, was encouraged to begin home libraries and those who were short of money were allowed to sit down and read.[3]

Politics and religion

Michaux was active in the Black nationalism movement from the 1930s to the 1960s and supported Marcus Garvey's Pan-Africanism.[3] Harlem had been the headquarters of Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League of the world—the largest mass black movement of the times.

Alagba (Elder) Michaux was a personal friend of Malcolm X and a member of the Organization of Afro-American Unity that was formed in 1964.[10]

When it came to religion, Michaux had a sign in the store reading "Christ is Black", but he also departed from his brother Lightfoot Solomon's affiliations with Christianity, saying: "The only lord I know, is the landlord."[3]

References

- Fraser, C. Gerald (August 27, 1976). "Lewis Michaux, 92, Dies; Ran Bookstore in Harlem". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Youel, Barbara Kraley (1976), Obituary. The New York Times, August 27, 1976 (also in American National Biography).

- Youel, Barbara Kraley (1976), Obituary. The New York Times, August 27, 1976. Also in American National Biography.

- The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 – A film by Göran Hugo Olsson (2011). Documentary, Sweden.

- Nelson, Vaunda Micheaux (2012). No Crystal Stair: A Documentary Novel of the Life and Work of Lewis Michaux, Harlem Bookseller. Minneapolis, MN: Carolrhoda Lab. ISBN 9780761387275.

No Crystal Stair: A Documentary Novel of the Life and Work of Lewis Michaux, Harlem Bookseller.

- Scorsese, Martin [Interviews by Jeff Rosen] (2005), No Direction Home. Documentary. Sony.

- Høg Hansen, Anders (2011), "Time and Transition in Oral and Written Testimonies". Unpublished conference paper given at Cultural Studies conference, Linköping University, June 2011, based on interviews with Izzy Young.

- Isserman, M., and M. Kazin (2008), America Divided. The Civil War of the 1960s, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 93.

- Michael Henry Adams, "Reading Amanda: One Black Man's Burden", The Huffington Post, May 13, 2009.

- Ade Oba Tokunbo, NYC resident, participant in Black Power mvmt., and customer of the store.