Li Guang

Li Guang (184-119 BC) was a Chinese military general of the Western Han dynasty. Nicknamed "Flying General" by the Xiongnu, he fought primarily in the campaigns against the nomadic Xiongnu tribes to the north of China. He was known to the Xiongnu as a tough opponent when it came to fortress defense, and his presence was sometimes enough for the Xiongnu to abort a siege.

Li Guang 李廣 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 184 BC |

| Died | 119 BC (aged 64-65) |

| Other names | "Flying General" (飛將軍) |

| Occupation | Military general |

| Children |

|

Li Guang committed suicide shortly after the Battle of Mobei in 119 BC. He was blamed for failing to arrive at the battlefield in time (after getting lost in the desert), creating a gap in the encirclement and allowing Ichise Chanyu to escape after a confrontation between Wei Qing and the Chanyu's main force, which the Han army narrowly managed to defeat. Refusing to accept the humiliation of a court-martial, Li Guang killed himself.

Li Guang belonged to the Longxi branch of the Li clan (隴西李氏). Li Guang was a descendant of Laozi and the Qin general Li Xin, as well as an ancestor of the Western Liang and Tang dynasty monarchs. Li Guang was the grandfather of general Li Ling who defected to the Xiongnu.

Life

According to Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian, Li Guang was a man of great build, with long arms and good archery skills, able to shoot an arrow deeply into a stone (which resembles the shape of a crouching tiger) on one occasion.[1] At the same time, like his contemporaries Wei Qing and Huo Qubing, he was a caring and well-respected general who earned the respect of his soldiers. He also earned the favor of Emperor Wen, who said of him: "If he had been born in the time of Emperor Gaozu, he would have been given a fief of ten thousand households (Chinese:万户侯) without any difficulty".

Li Guang first distinguished himself during the Rebellion of the Seven States, where he served under the Grand General Zhou Yafu. However, Emperor Jing was unhappy that he had accepted a seal given by Liu Wu, Prince of Liang, Emperor Jing's brother; Emperor Jing had been wary of the Prince of Liang, as Liu Wu had ambitions to place himself as Emperor Jing's successor, over Emperor Jing's sons. This stance was also supported by Empress Dowager Dou, their mother. Thus, Li did not get promoted to a marquisate despite his anti-rebellion achievement.

As the border of Hebei was always subject to constant attacks by the Xiongnu, Li Guang's valorous temper was deemed a good fit, and he was assigned to defend against them.[2]

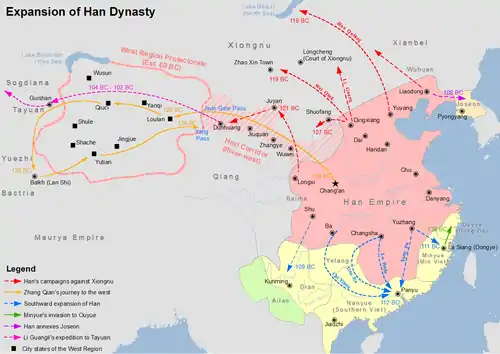

However, Li Guang's late military career was constantly haunted by repeated incidents of what would be regarded as jinxed with "bad luck" by later scholars. He had a nasty tendency of losing direction during mobilisations; in field battles, he was often outnumbered and surrounded by superior enemies. While Li Guang's fame attracted much of his enemies' attention, Li Guang's troops relative lack of discipline and his lack of strategic planning often put him and his regiments in awkward situations. Li Guang himself narrowly escaped capture after his army was annihilated during an offensive campaign at Yanmen in 129 BC, and was stripped of official titles and demoted to commoner status with fellow defeated general Gongsun Ao (公孫敖) after paying parole. During a separate campaign in 120 BC, Li Guang, this time with his son Li Gan (李敢) by his side, was surrounded again by superior enemies. His 4,000 troops suffered heavy casualties before reinforcements led by Zhang Qian (張騫) arrived in time for the rescue. The rules of the Han army dictated a commander's achievement was measured only according to his number of enemy kills minus the casualties of his own side. These, together with Li Guang's political naivety (as shown in the Prince of Liang incident), denied him of any chance of promotion to a marquisate, his lifelong dream. Emperor Wu even secretly ordered Wei Qing not to assign Li Guang to important missions (such as the vanguard position), on the grounds of Li Guang's famed "terrible fortune".

During the Battle of Mobei in 119 BC, an old but still enthusiastic Li Guang insisted Emperor Wu to promise him a vanguard position, but the emperor had secretly messaged generalissimo Wei Qing to not let Li lead the vanguard due to his infamy of "bad fortune". Wei Qing then assigned Li Guang to combine forces with Zhao Shiqi (赵食其/趙食其) on an eastern flanking route through a barren plain. Li Guang protested against the arrangement and angrily stormed out of the main camp. However, he and Zhao then got lost and missed the battle entirely, and only rejoining the main force after Wei Qing returned from a hard-fought victory against Yizhixie Chanyu's numerically superior army. As a result, Li and Zhao were summoned to a court martial to explain why they failed to accomplish orders and put the battle strategy at risk. Li Guang, frustrated and humiliated as this was his last chance to obtain sufficient merits to receive a marquessate as a reward, committed honor suicide. His son Li Gan blamed Wei Qing for his father's death, assaulted Wei and was later shot dead for the offence by his own superior Huo Qubing (who was Wei's nephew) during a hunting trip.

In popular culture

Li Guang is mentioned by his nickname in Wang Changling's seven-character quatrain "On the Frontier" (出塞). Wang comments on how war has been taking its toll on the troops stationed at the frontier, particularly given the lack of a brilliant and charismatic military commander like Li Guang.[3]

In the Imperial Japanese gunka Teki wa Ikuman, the song's lyrics reference Li Guang's ability to pierce a stone with an arrow as an example of determination regardless of difficulty.[4]

References

Citations

- Man, John (2019). Barbarians at the Wall The First Nomadic Empire and the Making of China (ebook). Transworld. ISBN 9781473554191. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- Brown, Kerry (2017). Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography (general history). Berkshire Publishing Group. p. 276. ISBN 9781933782614. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- Yang, 1993, p. 83-84

- "Thousands of enemies may come (Teki wa ikuman, 敵は幾万) 1890s". Retrieved December 9, 2019.

Bibliography

- Joseph P Yap. Wars With The Xiongnu - A translation From Zizhi Tongjian, Chapters 3-4. AuthorHouse (2009). ISBN 978-1-4490-0604-4.

- Yang, Jing Huey (1993). The study of Wang Changling’s seven-character quatrain (Master of Arts dissertation, University of British Columbia). Available from the UBC library database. Retrieved from https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.0087346.

- Theobald, Ulrich (2011). Li Guang 李廣; Cang Xiuliang 倉修良, ed. (1996). Hanshu cidian 漢書辭典 (Jinan: Shandong jiaoyu chubanshe), 296. Retrieved 13 January 2022.