Lie-to-children

A lie-to-children is a simplified, but false, explanation of technical or complex subjects as a teaching method for children and laypeople. The technique has been incorporated by academics within the fields of biology, evolution, bioinformatics and the social sciences. It is closely related to the philosophical concept known as Wittgenstein's ladder.

Origin

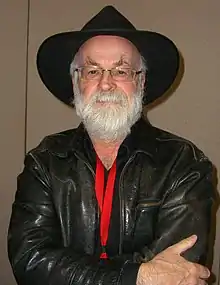

The "lie-to-children" concept was first discussed by scientist Jack Cohen and mathematician Ian Stewart in the 1994 book The Collapse of Chaos: Discovering Simplicity in a Complex World.[1][2][3] They further elaborated upon their views in their coauthored 1997 book Figments of Reality: The Evolution of the Curious Mind.[1][2][4] The concept gained greater exposure when they collaborated with popular author Terry Pratchett, discussing "lies-to-children" in the book The Science of Discworld (1999).[5][6]

Cohen and Stewart discussed "lies-to-children" and the desire inherent in society for a view of simplicity with regard to complex concepts in their 1994 book The Collapse of Chaos.[1][2][3][7]

Stewart and Cohen wrote in Figments of Reality (1997) that the lie-to-children concept reflected the difficulty inherent in reducing complex concepts during the education process.[4][8] Stewart and Cohen noted reality itself was viewed within the prism of human perspective: "Any description suitable for human minds to grasp must be some type of lie-to-children—real reality is always much too complicated for our limited minds."[4]

Librarian and editor Andrew Sawyer discussed the "lie-to-children" concept introduced by scientists Cohen and Stewart in their early two non-fiction books.[1][2] Sawyer wrote: "In The Collapse of Chaos and Figments of Reality, we also come across the concept of 'lies-to-children'—the necessarily simplified stories we tell children and students as a foundation for understanding so that eventually they can discover that they are not, in fact, true."[1][2]

The definition given in The Science of Discworld (1999) is as follows: "A lie-to-children is a statement that is false, but which nevertheless leads the child's mind towards a more accurate explanation, one that the child will only be able to appreciate if it has been primed with the lie".[9][10] The authors acknowledge that some people might dispute the applicability of the term lie, while defending it on the grounds that "it is for the best possible reasons, but it is still a lie".[5] This viewpoint is derived from earlier perspectives within the field of philosophy of science.[11]

In a 1999 interview, Pratchett commented upon the phrase: "I like the lies-to-children motif, because it underlies the way we run our society and resonates nicely with Discworld."[12][13] He was critical of problems inherent in early education: "You arrive with your sparkling A levels all agleam, and the first job of the tutors is to reveal that what you thought was true is only true for a given value of 'truth'."[12][13] Pratchett cautioned: "Most of us need just 'enough' knowledge of the sciences, and it's delivered to us in metaphors and analogies that bite us in the bum if we think they're the same as the truth."[12][13]

Cohen and Stewart further elaborated upon the lie-to-children trope in a 2002 book they coauthored on exobiology, Evolving the Alien: The Science of Extraterrestrial Life.[14] Within the work, the authors were critical of use of lie-to-children as an educational methodology which had an unfortunate side-effect of reducing complex science concepts to overly simplified explanations.[14] Stewart was asked in a 2015 interview about his views on Pratchett beyond the influence of lie-to-children, and the author's take on the understanding of science.[15] Stewart commented upon the interaction between himself and Cohen with Pratchett during the writing process: "Terry wasn't trained as a scientist, but he had the right kind of critical attitude. He was extraordinarily widely read, and would ask all sorts of unexpected questions that really got me and Jack thinking."[15]

Authors Michael Moorhouse and Paul Barry recommended the original works discussing the concept for further analysis of the phenomenon: "These are well worth a read if you fancy a laugh while pretending to work."[16]

Use in adult education

The term "lie to children" should not be taken to imply that it is exclusively used in childhood education. Educators in secondary and post-secondary schools employ increasingly accurate yet still "untrue" models as a means of explicating complex topics.

A typical example of this is found in physics, where the Bohr model of atomic electron shells is still often used to introduce atomic structure before moving on to more complex models based on matrix mechanics; and in chemistry, where the Arrhenius definitions of acids and bases are often introduced, followed (in a manner similar to the historical development of the model) by the Brønsted–Lowry definitions and then the Lewis definitions.

High school teachers and university instructors often explain at the outset that the model they are about to present is incomplete. An example of this is given by Gerald Sussman during the 1986 video recording of the Abelson-Sussman Lectures (lecture 1-b):

If we're going to understand processes and how we control them, then we have to have a mapping from the mechanisms of this procedure into the way in which these processes behave. What we're going to have is a formal, or semi-formal, mechanical model whereby you understand how a machine could, in fact, in principle, do this. Whether or not the actual machine really does what I'm about to tell you is completely irrelevant at this moment.

In fact, this is an engineering model, in the same way that, [for an] electrical resistor, we write down a model V = IR—it's approximately true, but it's not really true; if I put enough current through the resistor, it goes boom, so the voltage is not always proportional to the current, but for some purposes the model is appropriate.

In particular, the model we're going to describe right now, which I call the substitution model, is the simplest model that we have for understanding how procedures work and how processes work—how procedures yield processes.

And that substitution model will be accurate for most of the things we'll be dealing with in the next few days. But eventually, it will become impossible to sustain the illusion that that's the way the machine works, and we'll go to other, more specific and particular models that will show more detail.

Analysis

The concept of lie-to-children was discussed at-length in 2000 by Andrew Sawyer, where the subject itself was included in the article title: "Narrativium and Lies-to-Children: 'Palatable Instruction in 'The Science of Discworld'".[1][2] Sawyer wrote that: "The 'lies-to-children' we tell ourselves about science are a different form of science fiction: one, perhaps where 'fiction' qualifies the word 'science'. They are 'fictions about science' rather than 'science fictions'."[1][2] Sawyer concluded: "The strength of The Science of Discworld—and why in many ways it is something new in science writing—derives from Pratchett's story being more than a parable constructed for the specific purpose of explaining what the scientists have to say. It is, as has been said, a commentary/parody of the scientific method".[1][2]

In a contribution about evolution for the 2001 book Nonlinear Dynamics in the Life and Social Sciences, reproductive biologist Jack Cohen discussed the lie-to-children teaching technique and its use educating students on the concept of evolution and its complex facets including the notion that DNA is an architectural guide for life.[17] The author concluded: "Only the search for universal features, while treasuring all the exceptional specifics, offers some hope of sketching out the general shape of the evolutionary process so that we can explain it honestly as a Lie-to-Children."[17]

D.J. Jeffrey and Robert M. Corless of the Ontario Research Centre for Computer Algebra at the University of Western Ontario wrote in their 2001 computer science paper on linear algebra instruction on the teaching concept.[6] Jeffrey and Corless identified a "useful" lie-to-children, as one in which: "The pedagogical point is to avoid unnecessary burdens on the student’s first encounter with the concept."[6] The authors gave an example from early childhood mathematics instruction: "We happily teach children that 'you cannot take 3 from 2' because we are confident that someone will later introduce them to negative numbers."[6] Corless further expounded on this view in a subsequent paper published in 2004, writing: "A 'lie to children' is a useful oversimplification that starts one on the path to better knowledge. It is a truth unacknowledged that mathematics before computers was a lie to children."[18]

In their 2004 book Bioinformatics, Biocomputing and Perl, authors Michael Moorhouse and Paul Barry explained how the lie-to-children model may be utilized as a teaching technique for the concepts of protein, RNA, and DNA.[16] Moorhouse and Barry wrote that the lie-to-children methodology can reduce complex academic notions to a simpler format for basic understanding.[16] The authors conclude that the lie-to-children teaching technique: "allows the basic features to be understood without confusing things by considering exceptions and enhancements."[16]

Haroom Kharem and Genevieve Collura were critical of the teaching practice, in a contribution to the 2010 book Teaching Bilingual/Bicultural Children.[19] The authors wrote that using this teaching method was a form of disrespect for the truth.[19] Kharem and Collura lament that rather than imparting truth to children, "a pedagogy of stupidification is promoted in which teachers imbue students with untruths and then wonder why education has problems. Sooner or later the fabrications we teach students will come to light and the respect educators expect from students will become disingenuous."[19]

North Eastern Hill University economics professor Sudhanshu K. Mishra in 2010 defined the phrase as: "A lie-to-children is a lie, often a platitude, which may use euphemism(s), which is told to make an adult subject acceptable to children."[20] Mishra gave as an example parents who engage in mythology by lying to their children and telling them they were brought by a stork to the house, instead of explaining childbirth.[20] In a 2011 contribution to the academic journal Digital Difference, Hamish Macleod and Jen Ross discussed the lie-to-children concept and wrote that this teaching methodology can have the negative impact of introducing studying difficulties to students as they progress further in their education.[21] They cautioned this could lead to a negative influence on students' future behaviors.[21] Macleod and Ross wrote: "Playing devil's advocate is in itself a challenging notion for many learners, who may, especially in their early years of higher education, be conditioned by what Stewart and Cohen call 'lies to children' to expect simple and unambiguous questions and equally simple answers."[21]

Writing in 2011 for the Carleton College website, geophysicist Kim Kastens in a column with her daughter at first found the notion of lie-to-children as surprising.[22] Kastens delved further into the issue, and identified specific instances where a lie-to-children teaching technique would do more harm than good for students.[22] The worst examples included a lie-to-children which would later have to be unlearned following teaching from subsequent professors, an instance where the student is successfully able to identify the factual inaccuracy and knows more about it than the teacher, and using the technique without having a "master plan" involving progressive learning.[22] In her 2011 book The Children's Bill of Emotional Rights, Eileen Johnson discussed the lies told by parents to their children during the formation of childhood fictional mythology and pointed out the inherent problems this could raise in the future during the parenting process.[23] Johnson cautioned: "Why do we tell these lies to children? At some point we have to admit we were lying. Parents are not sure how much of this deceit is right, how far to go with it, and how and when to explain it was all a lie."[23]

Kirsten Walsh and Adrian Currie contributed a 2015 article to the journal Metaphilosophy in which they quoted the verbatim definition of lie-to-children from The Science of Discworld and discussed the impact of such behavior on students.[9] Walsh and Currie concluded that mythmaking within education in order to teach a more complex concept is a form of unwarranted behavior with detrimental impact upon instruction methodology.[9] In a 2015 article, The Conversation compared the concept to Wittgenstein's ladder, and defined it: "that in order to get across a complicated idea, sometimes you need to use an explanation that is actually wrong but which helps a child—or anyone learning about anything complex—build an understanding of that issue."[24]

Writing for Forbes in 2015, physics professor and science journalist Chad Orzel explained the concept: "Lies-to-children are not strictly true, but they’re simplified in a way that makes them easier to grasp for children, and provide a framework that allows for future elaboration."[25] Orzel praised the University of California Museum of Paleontology initiative Understanding Science for its strategy of going beyond a simple explanation of the scientific method in a lie-to-children format, and instead going into more depth and specifics to directly inform others on how science impacts their daily quality of living.[25]

British writer Tim Worstall expounded upon the lie-to-children phenomenon in education, in a 2015 article for Forbes.[26] He wrote: "that’s what Terry Pratchett pointed out education was: lies to children to help them make some sense of the world. When they become older, more capable of nuance, then we point this out to them: those previous stories were gross simplifications and now you need to know the caveats."[26] Worstall stressed that this form of educational methodology was ubiquitous across multiple academic disciplines: "This is true of any form of education (...) [w]e don’t start music classes with atonality, we start with simple scales. We don’t do syncopation until we’ve mastered 2/4 and 4/4. Einstein’s corrections at the margin to Newton come quite late in a physics education."[26]

See also

- Age appropriateness – Expected behaviour of a person for their age

- All models are wrong – Common aphorism in statistics

- Discworld (world) – Fictitious setting in the Discworld franchise

- Half-truth – Deceptive statement

- List of common misconceptions

- Misinformation – Incorrect information with or without an intention to deceive

- Naïve physics – untrained human perception of basic physical phenomena

- Neurath's boat – Philosophical analogy about knowledge

- Noble lie – Untruth propagated to strengthen social harmony

- Not even wrong – English phrase

- Pedagogy – Theory and practice of education

- Sunday school answer

- Toy model – Deliberately simplistic scientific model

- Understanding – Ability to think about and use concepts to deal adequately with a subject

- Upaya – Buddhist term

- White lie – Intentionally false statement made to deceive

- Wittgenstein's ladder – Concluding and reflective remark on the propositions in Wittgenstein's early work

References

- Sawyer, Andy (2000). "Narrativium and Lies-to-Children: 'Palatable Instruction in 'The Science of Discworld'". Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies (HJEAS). Centre for Arts, Humanities and Sciences (CAHS), acting on behalf of the University of Debrecen CAHS. 6 (1): 155–178. ISSN 1218-7364. JSTOR 41274079.

- Sawyer, Andrew (2007). "Narrativium and Lies-to-Children: 'Palatable Instruction in 'The Science of Discworld'". In Butler, Andrew M. (ed.). An Unofficial Companion to the Novels of Terry Pratchett. Greenwood. pp. 80–82. ISBN 978-1-84645-043-3.

- Cohen, Jack; Stewart, Ian (1994). The Collapse of Chaos: Discovering Simplicity in a Complex World. Penguin Books. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-0-670-84983-3.

- Stewart, Ian; Cohen, Jack (1997). Figments of Reality: The Evolution of the Curious Mind. Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–38, 140. ISBN 978-0-521-57155-5.

- Pratchett, Terry; Stewart, Ian; Cohen, Jack (2014). The Science of Discworld. Anchor; 2014 Reprint Edition of 1999 book; Paperback. pp. 28–30. ISBN 978-0-8041-6894-6.

- Jeffrey, D.J.; Corless, Robert M. (2001). "Teaching Linear Algebra with and to Computers" (PDF). Ontario Research Centre for Computer Algebra at the University of Western Ontario. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- "Nonfiction Book Review: The Collapse of Chaos". Publishers Weekly. April 1994. Archived from the original on 27 February 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Chapman, Douglas (1997). "Book Review – Figments of Reality: The Evolution of the Curious Mind". Strange Magazine. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- Walsh, Kirsten; Currie, Adrian (22 July 2015). "Caricatures, Myths, and White Lies" (PDF). Metaphilosophy. 46 (3): 414–435. doi:10.1111/meta.12139. hdl:10871/35769. ISSN 1467-9973.

- Fallis, Don (2015). "What Is Disinformation?" (PDF). Library Trends. 63 (3): 401–426. doi:10.1353/lib.2015.0014. hdl:2142/89818. ISSN 0024-2594. S2CID 13178809.

- Judge, Anthony (1 July 2007). "Strategic leadership as essentially a "shell game" with potential opponents, followers and dissidents?". Emergence of a Global Misleadership Council – misleading as vital to governance of the future?. Laetus in Praesens. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- Langford, David (2015). "Terry Pratchett, Jack Cohen and Ian Stewart: 1999". CROSSTALK: Interviews Conducted by David Langford. Lulu.com; Republished from: Amazon.co.uk, 1999. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-1-326-29982-8.

- Langford, David (1999). "Weird Science". Amazon.co.uk. The L-Space Web: Interviews – Interview Conducted by Amazon.co.uk with Terry Pratchett, Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen. Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- Langford, David (5 October 2002). "Evolving the Alien: The science of extraterrestrial life by Jack Cohen and Ian Stewart". New Scientist. ISSN 0262-4079. Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- Jordison, Sam (9 June 2015). "Ian Stewart on the science of Terry Pratchett's Discworld – as it happened". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- Moorhouse, Michael; Barry, Paul (2004). Bioinformatics Biocomputing and Perl: An Introduction to Bioinformatics Computing Skills and Practice. Wiley. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-0-470-85331-3.

- Cohen, Jack (2001). "Complexity of Evolution". In Sulis, William H.; Trofimova, Irina Nikolaevna (eds.). Nonlinear Dynamics in the Life and Social Sciences. NATO Science, Series A: Life Sciences, Vol. 320. IOS. pp. 357–359. ISBN 978-1-58603-020-9.

- Corless, Robert M. (July 2004). "Computer-Mediated Thinking" (PDF). ORCCA and the Department of Applied Mathematics at the University of Western Ontario. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Kharem, Haroom; Collura, Genevieve (2010). "Chapter Seventeen: Teachers Rethinking Their Pedagogical Attitudes in the Bicultural/Bilingual Classroom". In Soto, Lourdes Diaz; Kharem, Haroon (eds.). Teaching Bilingual/Bicultural Children: Teachers Talk about Language and Learning. Counterpoints (Book 371). Peter Lang Publishing. pp. 152–155. ISBN 978-1-4331-0718-4. JSTOR 42980693.

- Mishra, Sudhanshu K. (23 May 2010). "An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Deception and Telling Lies". Munich Personal RePEc Archive; MPRA Paper No. 22906. Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- Macleod, Hamish; Ross, Jenn (2011). "Structure, Authority and Other Noncepts1" (PDF). Digital Difference. pp. 15–28. doi:10.1007/978-94-6091-580-2_2. ISBN 978-94-6091-580-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Kastens, Kim; Chayes, Dana (26 October 2011). "Telling Lies to Children". Earth and Mind. Carleton College. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- Johnson, Eileen (2011). The Children's Bill of Emotional Rights: A Guide to the Needs of Children. Jason Aronson, Inc. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-0-7657-0850-2.

- "Netanyahu's narrative: how the Israeli PM is rewriting history to suit himself". The Conversation. 27 October 2015. Archived from the original on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Orzel, Chad (3 November 2015). "'The Scientific Method' Is A Myth, Long Live The Scientific Method". Forbes. Archived from the original on 12 November 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- Worstall, Tim (25 November 2015). "To Prove Econ 101 Is Wrong You Do Need To Understand Econ 101". Forbes. Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

Further reading

- Orzel, Chad (3 November 2015). "'The Scientific Method' Is A Myth, Long Live The Scientific Method". Forbes. Archived from the original on 12 November 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- Pratchett, Terry; Stewart, Ian; Cohen, Jack (2014). The Science of Discworld. Anchor; 2014 Reprint Edition of 1999 book; Paperback. pp. 28–30. ISBN 978-0-8041-6894-6.

- Sawyer, Andy (2000). "Narrativium and Lies-to-Children: 'Palatable Instruction in 'The Science of Discworld'". Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies (HJEAS). Centre for Arts, Humanities and Sciences (CAHS), acting on behalf of the University of Debrecen CAHS. 6 (1): 155–178. ISSN 1218-7364. JSTOR 41274079.

- Stewart, Ian; Cohen, Jack (1997). Figments of Reality: The Evolution of the Curious Mind. Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–38, 140. ISBN 978-0-521-57155-5.

- Worstall, Tim (25 November 2015). "To Prove Econ 101 Is Wrong You Do Need To Understand Econ 101". Forbes. Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

External links

- "Lies-to-children". Scientific Scribbles. University of Melbourne. 17 August 2012. Archived from the original on 12 July 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- Kastens, Kim; Chayes, Dana (26 October 2011). "Telling Lies to Children". Earth and Mind. Carleton College. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- "Lies-to-Children". Discworld & Terry Pratchett Wiki. The L-Space Web. 12 January 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- Nineteenthly (5 March 2013). "Lying to Children". YouTube. Retrieved 26 February 2016.