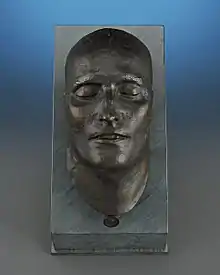

Death mask

A death mask is a likeness (typically in wax or plaster cast) of a person's face after their death, usually made by taking a cast or impression from the corpse. Death masks may be mementos of the dead or be used for creation of portraits.

The main purpose of the death mask from the Middle Ages until the 19th century was to serve as a model for sculptors in creating statues and busts of the deceased person. Not until the 1800s did such masks become valued for themselves.[1]

In other cultures a death mask may be a funeral mask, an image placed on the face of the deceased before burial rites, and normally buried with them. The best known of these are the masks used in ancient Egypt as part of the mummification process, such as the mask of Tutankhamun, and those from Mycenaean Greece such as the Mask of Agamemnon.

In some European countries, it was common for death masks to be used as part of the effigy of the deceased, displayed at state funerals; the coffin portrait was an alternative. Mourning portraits were also painted, showing the subject lying in repose. During the 18th and 19th centuries masks were also used to permanently record the features of unknown corpses for purposes of identification. This function was later replaced by post-mortem photography.

When taken from a living subject, such a cast is called a life mask.

History

Sculptures

Masks of deceased people are part of traditions in many countries. The most important process of the funeral ceremony in ancient Egypt was the mummification of the body, which, after prayers and consecration, was put into a sarcophagus enameled and decorated with gold and gems. A special element of the rite was a sculpted mask, put on the face of the deceased. This mask was believed to strengthen the spirit of the mummy and guard the soul from evil spirits on its way to the afterworld. The best known mask is Tutankhamun's mask. Made of gold and gems, the mask conveys the highly stylized features of the ancient ruler. Such masks were not, however, made from casts of the features; rather, the mummification process itself preserved the features of the deceased.

In 1876 the archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann discovered in Mycenae six graves, which he was confident belonged to kings and ancient Greek heroes—Agamemnon, Cassandra, Evrimdon and their associates. To his surprise, the skulls were covered with gold masks. It is now thought most unlikely that the masks actually belonged to Agamemnon and other heroes of the Homeric epics; in fact they are several centuries older.

The lifelike character of Roman portrait sculptures has been attributed to the earlier Roman use of wax to preserve the features of deceased family members (the so-called imagines maiorum). The wax masks were subsequently reproduced in more durable stone.[2]

The use of masks in the ancestor cult is also attested in Etruria. Excavations of tombs in the area of the ancient city of Clusium (modern Chiusi, Tuscany) have yielded a number of sheet-bronze masks dating from the Etruscan late orientalizing period.[3] In the 19th century it was thought that they were related to the Mycenaean examples, but whether they served as actual death masks cannot be proven. The most credited hypothesis holds that they were originally fixed to cinerary urns, to give them a human appearance. In Orientalising Clusium, the anthropomorphization of urns was a prevalent phenomenon that was strongly rooted in local religious beliefs.

Casts

The Roman élites used during the funerals "death masks" which were in fact casts made during life. These masks were displayed, after one's death in his family's atrium as a sign of social and political prominence. This usage was already established by the 2nd century BC and continued to be used into the 4th and perhaps as late as the 6th century AD.[4] In the late Middle Ages, the masks were not interred with the deceased. Instead, they were used in funeral ceremonies and were later kept in libraries, museums, and universities. Death masks were taken not only of deceased royalty and nobility (Henry VIII, Sforza), but also of eminent people: composers, dramaturges, military and political leaders, philosophers, poets, and scientists, such as Dante Alighieri, Ludwig van Beethoven, Napoleon Bonaparte (whose death mask was taken on the island of Saint Helena), Filippo Brunelleschi, Frédéric Chopin, Oliver Cromwell (whose death mask is preserved at Warwick Castle), Joseph Haydn, John Keats, Franz Liszt, Blaise Pascal, Nikola Tesla (commissioned by his friend Hugo Gernsback and now displayed in the Nikola Tesla Museum), Torquato Tasso, Richard Wagner and Voltaire.

In Russia, the death mask tradition dates back to the times of Peter the Great, whose death mask was taken by Carlo Bartolomeo Rastrelli. Also well known are the death masks of Nicholas I, and Alexander I. Stalin's death mask is on display at the Stalin Museum in Gori, Georgia.

One of the first real Ukrainian death masks was that of the poet Taras Shevchenko, taken by Peter Clodt von Jürgensburg in St. Petersburg, Russia.[5]

In early spring of 1860 and shortly before his death in April 1865, two life masks were created of President Abraham Lincoln.[6]

Science

Death masks were increasingly used by scientists from the late 18th century onwards to record variations in human physiognomy. The life mask was also increasingly common at this time, taken from living people.

Forensic science

Before the widespread availability of photography, the facial features of unidentified bodies were sometimes preserved by creating death masks so that relatives of the deceased could recognize them if they were seeking a missing person.

One mask, known as L'Inconnue de la Seine, recorded the face of an unidentified young girl who, around the age of 16, according to one man's story, had been found drowned in the Seine River in Paris around the late 1880s. A cast of her face was made by a morgue worker who explained that "her beauty was breathtaking and showed few signs of distress at the time of passing. So bewitching that I knew beauty as such must be preserved." The cast was also compared to the Mona Lisa and other famous paintings and sculptures. Copies of the mask were fashionable in Parisian Bohemian society, and the face of Resusci Anne, the world's first CPR training mannequin, introduced in 1960, was modeled after the mask.[7][8]

See also

References

- Wallechinsky, Irving; Wallace, Irving (1978). The People's Almanac #2. New York: Bantam Books. pp. 1189–1192. ISBN 0553011375.

- H.W. Janson with Dora Jane Janson, History of Art: A Survey of the Major Visual Arts from the Dawn of History to the Present Day, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, and New York, Harry N. Abrams, 1962, p. 141.

- N. Steensma, Some considerations on the function and meaning of the Etruscan bronze "masks" from Chiusi (seventh century BC), in: H. Duinker, E. Hopman & J. Steding (eds.), Proceedings of the 11th annual Symposium Onderzoek Jonge Archeologen, Groningen 2014, pp. 65–74 Archived 2017-04-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Rose, .Brian"Recreating Roman Wax Masks" Expedition Magazine 56.3 (2014): n. pag. Expedition Magazine. Penn Museum, 2014 Web. 31 Jan 2022". Archived from the original on 21 June 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- Virtual Museum of Death Mask Archived 2018-03-08 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed on December 4, 2006.

- "Portraits of the Presidents". National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Smithsonian Institution. 21 August 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- Laerdal company website: The Girl from the River Seine Archived 2012-03-24 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed on January 8, 2013

- Gordon, AS. "A death mask to help save lives" (PDF). Wexford, Pennsylvania: Sudden Cardiac Arrest Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

External links

- The International Life Cast Museum

- Laurence Hutton Collection of Life and Death Masks Archived 2006-03-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Collection of Death Masks History of death masks, Pictures of death masks and historical resources

- Episode of Radiolab discussing death masks (specifically L'Inconnue de la Seine)

.jpg.webp)