Limburg (Belgium)

Limburg (Dutch: Limburg, pronounced [ˈlɪmbʏr(ə)x] ⓘ; Limburgish: Limburg [ˈlɪm˦ˌbɵʀ˦(ə)ç] or Wes-Limburg [wæsˈlɪm˦ˌbɵʀ˦(ə)ç]; French: Limbourg, pronounced [lɛ̃buʁ] ⓘ) is a province in Belgium. It is the easternmost of the five Dutch-speaking provinces that together form the Region of Flanders, one of the three main political and cultural sub-divisions of modern-day Belgium.

Limburg | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Anthem: "Limburg mijn Vaderland" "Limburg My Fatherland" | |

| |

| Coordinates: 50°36′N 5°56′E | |

| Country | |

| Region | |

| Capital (and largest city) | Hasselt |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Jos Lantmeeters |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,427 km2 (937 sq mi) |

| Population (1 January 2019 [2]) | |

| • Total | 874,048 |

| • Density | 360/km2 (930/sq mi) |

| ISO 3166 code | BE-VLI |

| Gross Regional Product[3] | 2021 |

| - Total | €31.766 billion |

| - Per capita | €36,300 |

| HDI (2019) | 0.925[4] very high · 7th of 11 |

| Website | www |

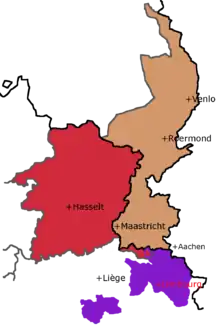

Limburg is located west of the Meuse (Dutch: Maas), which separates it from the similarly-named Dutch province of Limburg. To the south it shares a border with the French-speaking province of Liège, with which it also has historical ties. To the north and west are the old territories of the Duchy of Brabant. Today these are the Flemish provinces of Flemish Brabant and Antwerp to the west, and the Dutch province of North Brabant to the north.

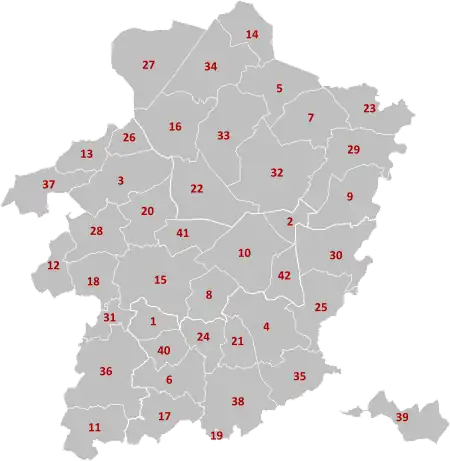

The province of Limburg has an area of 2,427 km2 (937 sq mi) which comprises three arrondissements (arrondissementen in Dutch) containing 44 municipalities. Among these municipalities are the current capital Hasselt, Sint-Truiden, Genk, and Tongeren, which is the only Roman city in the province, and regarded as the oldest city of Belgium. As of January 2019, Limburg has a population of 874,048.[5]

The municipality of Voeren is geographically detached from Limburg and the rest of Flanders, with the Netherlands to the north and the Walloon province of Liège to the south. This municipality was established by the municipal reform of 1977 and on 1 January 2008 with its six villages had a total population of 4,207. Its total area is 50.63 km2 (19.55 sq mi).

Name

The name Limburg was not applied to the territory of Belgian Limburg until the 19th century. Instead, the territory broadly coincides with that of the medieval County of Loon, which was one of the main parts of the Prince-bishopric of Liège. In the late-18th century, following the French Revolution and the Campaign in the Low Countries, the region became part of the newly created Lower Meuse Department of the French First Republic (later the First French Empire), along with a significant part of what would become Dutch Limburg.

After the defeat of the French empire and the Congress of Vienna in 1815, this department was reconstituted into the Province of Limburg as part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. The new name had its own medieval history, being associated with the extinct Duchy of Limburg, which had its capital at nearby Limbourg-sur-Vesdre, now in the French-speaking Belgian province of Liège. The new Dutch monarchy chose this name because it desired to recreate the prestigious old title in a new Duchy of Limburg.

Because of the Belgian revolution in 1830, this province of Limburg was divided in 1839 by the Treaty of London; the western portion being recognised as a province of the newly-formed Kingdom of Belgium, while the eastern portion remained part of the Netherlands as the modern Dutch Province of Limburg. Both parts retained the name they had been given by the Dutch monarchy after the defeat of France.

History

The first wave of people who brought farming and pottery technology from the Middle East to northern Europe was the LBK culture, which originated in central Europe and reached a geographical limit in the fertile southern Haspengouw part of Limburg about 5000 BC, only to die out about 4000 BC. A later wave of people from this farming culture, the Michelsburg culture, arrived from central Europe about 3500 BC and shared a similar fate. Pottery technology had however apparently been taken up by local tribes of the Swifterbant culture, who remained present throughout.

The area became permanently agricultural only in the Bronze Age with the Urnfield culture around 1200 BC, followed by the possibly related Halstatt and La Tène material cultures, which are generally associated with Celts. Under these cultures the population increased in the region, and it is also during this period that Indo-European languages are thought to have arrived. Although these new technologies and languages once again arrived from the direction of Germany, they can partly be traced back to peoples who arrived in Europe, not from the Middle East, but from the direction of Ukraine and southern Russia around 2000 BC. This migration had a similar impact across the continent.

Caesar gave the first surviving written description of the area around 55 BC and described its people as the Germani cisrhenani. He described them as allies of the Belgae and Treveri, and reported that they had ancestral links with their neighbours on the east side of the Rhine. Somewhat earlier, we know from surviving fragments of his work that Poseidonius had already mentioned these same Germani, saying that they roasted meat in separate joints, and drank milk and unmixed wine.[6] Caesar noted several peoples within the Germani group, the most important of which were the Eburones who fought against Julius Caesar under their leaders Ambiorix and Cativolcus. Apart from the Germani, somewhere to the west of the Eburones (possibly outside Limburg) were the Aduatuci, who Caesar reported to be the descendants of the Cimbri and Teutones who had migrated around Europe some generations before Caesar.

Under Roman imperial rule, the area was known as the "city" (civitas) the Tungri. Tacitus reported that these Tungri were the same as the earlier Germani cisrhenani, and noted that the use of the name "Germani" had been expanded in Roman times to cover many peoples in Germany east of the Rhine. The Tungri are generally accepted to have been speakers of a Germanic language, but modern historians disagree over the extent to which they descend from new immigrants who came from over the Rhine after Caesar. Notably, the Tungri participated on the Roman side in the revolt of the Batavi against Roman rule, which was a major event in this region.[7] In the north of Limburg during Roman times lived the Texandri.

The site of the fort where Caesar's soldiers encamped was called Aduatuca. This was apparently a general word for a fort, associated not only with the Eburones, but also the Aduatuci, and the later Tungri. The Roman city established in Belgian Limburg was referred to as Aduatuca Tungrorum meaning "Aduatuca of the Tungri". Today this has become "Tongeren", in the southeast of Belgian Limburg, and it was the capital of a Roman administrative region called the "Civitas Tungrorum". Under the Romans, the Tungri civitas was first a part of Gallia Belgica, and this was later split out with the more militarized border regions between it and the Rhine, to become Germania Inferior, which was later converted into Germania Secunda.[8]

In late Roman and early medieval times, the northern or "Kempen" part of Belgian Limburg became depopulated and uncultivated. This area, still known then by its Roman name as Texandria, was settled by incoming Salian Franks from the north, who were under pressure from Saxons. The southern or "Haspengouw" part of Belgian Limburg was an important agricultural region and remained more heavily Romanised, and eventually became a core land of the Frankish empires.

Middle Ages

By the 9th century, the Frankish Carolingian dynasty, who had lands in and around Belgian Limburg, ruled an empire that included much of Western Europe. The Franks originally had several smaller kingdoms ruling each of the old Roman civitates, but under the Merovingians one empire formed, which was divided each generation among family members. In the period around 881 and 882 the areas along the Maas and in the Haspengouw were plundered by Vikings, who established a base on the Maas river. Early Christianity was established first in the Romanised southern parts of Limburg, around Tongeren, and missionaries went north from there to convert the Franks. The church capital moved to nearby Maastricht, and then Liège, this was the area of activity of St Servatius, and later, Lambert of Maastricht.

Limburg was part of the central Austrasian kingdom of the Franks which lay between the parts which would become France and Germany. A version of these divisions was eventually fixed in the 9th century when this Middle Kingdom came to be known as Lotharingia after its first king, Lothair II. During the 10th-century the region slowly came under the permanent control of Eastern Francia, which was to become the Holy Roman Empire. Under the Ottonians the archbishops became responsible for a very large territory stretching up to the delta of the river Maas. Another early saint in the south of Limburg was St Trudo, whose name survives in one of the major towns in southern Limburg.

Belgian Limburg corresponds closely to the medieval territory of the County of Loon (French Looz) which starts to appear in records only in the 11th century. This county originally centred on the fortified town of Borgloon, which was originally simply known as Loon. Although the exact details are unclear today, from an early time Loon was subservient, not only spiritually but also politically, to the powerful Prince-Bishopric of Liège. When the male line of the counts ended with Louis IV in 1336, the bishops began to take direct control, and the last claimant to that inheritance, Arnold of Rumigny, count of Chiny gave up his claim.

Modern history

Loon, and the rest of the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, were not joined politically with the rest of what would become Belgium until the French revolution. Nevertheless, in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries the population of Loon was constantly and badly affected by the large-scale international wars of the neighbouring Spanish Netherlands and Dutch Republic, including the Eighty Years' War, the Nine Years' War, the War of the Spanish Succession, the War of the Austrian Succession, the Seven Years' War, and even the Brabant Revolution. During this period the region's episcopal government was often unable to maintain law and order, and the economy of the area was often desperately bad, affected by plundering soldiers and gangs of thieves such as the "Bokkenrijders". Nevertheless, the population contained strongly conservative Catholic elements, and not only supported the conservative Brabant revolution, but also rebelled unsuccessfully against the revolutionary French regime in the Peasants' War of 1798.

The modern Limburg region, containing the Belgian and Dutch provinces of that name, were first united within one province while under the power of revolutionary France, and later the Napoleonic empire, but then under the name of the French department of the Lower Meuse (Maas). After Napoleon's defeat, a united Kingdom of the Netherlands was formed, containing modern Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. While it kept many of the French provincial boundaries, the first king, William I, insisted that the name be changed to the "Province of Limburg", based on the name of the medieval Duchy of Limburg. The only part of Belgian or Dutch Limburg which was really in the Duchy of Limburg is the extreme east of Voeren, the villages of Teuven and Remersdaal, and these only became part of Belgian Limburg in 1977.

After the Belgian Revolution of 1830, the province of Limburg was at first almost entirely under Belgian rule, but the status of both Limburg and Luxembourg became unclear. During the "Ten days campaign", 2–12 August 1831, Dutch armies entered Belgium and took control of several Belgian cities in order to negotiate from a stronger position. Several Belgian militias and armies were easily defeated including the Belgian Army of the Meuse near Hasselt, on 8 August. The French and British intervened, leading to a ceasefire. After a Conference in London, they signed a treaty in 1839 and established after that both Limburg and Luxemburg would be split between the two states. That happened; Limburg was split into so-called Dutch Limburg and Belgian Limburg.

Twentieth century

Belgian Limburg became officially Flemish when Belgium was divided into language areas in 1962. In the case of Voeren, surrounded by French speaking parts of Belgium, and having a significant population of French speakers, this was not without controversy.

Only in 1967, the Catholic Church created a diocese of Hasselt, separate from the diocese of Liège.

Geography

The centre of Belgian Limburg is crossed east to west by the river Demer and the Albert Canal, which run similar paths. The Demer's drainage basin covers most of the central and southern part of the province, except for the southeastern corner, where the Jeker (in French: (le) Geer) runs past Tongeren and into the river Maas (in French: (la) Meuse) at Maastricht.

The eastern border of the province corresponds to the western bank of the Maas, which originates in France. Its drainage basin includes not only the Jeker but most of the northern part of Belgian Limburg.

The south of the province is the northern part of the Hesbaye region (in Dutch: Haspengouw), with fertile soils, farming and fruit-growing, and historically the higher population density. The hilliness increases in the southeast, including the detached Voeren part of Limburg.

North of the river Demer and the Albert Canal is part of the Campine (in Dutch: (de) Kempen) region, with sandy soils, heathlands, and forests. This area was relatively less populated, until coal-mining started in the 19th century, attracting immigration from other areas, including Mediterranean countries.

Language

As in all Flemish provinces, the official language is Dutch, but two municipalities, Herstappe and Voeren, are to a certain extent allowed to use French to communicate with their citizens. They are two of the municipalities with language facilities in Belgium.

Several variations of Limburgish are also still actively used, these being a diverse group of dialects which share features in common with both German and Dutch. Limburg mijn Vaderland is the official anthem of both Belgian and Dutch Limburg, and has versions in various dialects of Limburgish, varying from accents closer to standard Dutch in the west, to more distinctive dialects near the Maas. Outside of the two Limburgs related dialects or languages are found stretched out towards the nearby Ruhr valley region of Germany. And there are also related dialects around Aachen in Germany as well as in the extreme northeast of the mainly French-speaking province of Liège.

As in the rest of Flanders a high level of multi-lingualism is found in the population.

Limburg is close to Germany and Wallonia, and because of the natural political, cultural and economics links, French and German have long been important second languages in the area.

English has also now become a language which is widely understood and used in business and cultural activities, and is supplanting French in this regard.

Veldeke, the medieval property of the family of Hendrik van Veldeke, was near Hasselt, along the river Demer, to the west of Kuringen.

Economy

The Gross domestic product (GDP) of the province was 28.7 billion € in 2018. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was 29,000 € or 96% of the EU27 average in the same year.[9]

In the economic field tourism is being actively promoted with publicized attractions including Limburg's claim to be a "Bicycle Paradise" (Fietsparadijs). There's also the possibility to walk in nature reserves, such as the "High Kempen National Park".[10][11]

In the south, the Haspengouw (Hesbaye), predominantly situated in Limburg, is now Belgium's major area for fruit growing. In Limburg more than 50% of Belgium's fruit production is grown.

Coal mining has been an important industry in the 20th century,[12] but has now ended in this province. Nevertheless, it has laid the basis for a more complex modern economy and community. In the 20th century, Limburg became a centre for the secondary sector, attracting Ford, who had a major production centre in Genk that closed in December 2014, and the electronics company Philips, who had a major operation in Kiewit.

Many areas such as Genk continue to have a lot of heavy and chemical industry, but emphasis has moved towards encouraging innovation. The old Philips plant is now the site of a Research Campus,[13] and the Hasselt University in Diepenbeek has a science park attached to it. Similarly, the site of the coal mine in Genk is now Thor Park, where Energyville, a research hub of the KU Leuven, VITO, imec, and UHasselt.

The region today promotes itself as a centre for trade in the heart of industrialised Europe. It is part of the Meuse-Rhine Euroregion, which represents a partnership between this province and neighbouring provinces in Germany, the Netherlands and Wallonia.

Culture

Essential elements in Limburgian culture are:

- Music (many places have their own brass-band; from 1965 until 1981 yearly an internationally known jazz- en rockfestival took place at Bilzen, before it moved outside of Limburg to Werchter, where it is still held, by now as "Rock Werchter"). Another well known yearly music festival is Pukkelpop in Hasselt.

- Religion predominantly Roman Catholic[14]

- Folklore several places still have a now folkloristic "citizen force".

- Carnival

- Sports, of which especially bicycle racing[15] and soccer are most popular. Professional soccer clubs playing in the three highest national divisions are: K.R.C. Genk and K. Sint-Truidense V.V. (Division 1), Lommel United (Division 2); K. Patro Eisden Maasmechelen and KSK Hasselt (Division 3). K.R.C. Genk have won the national championship four times. Motocross is also popular, with four former world champions in this sport coming from Belgian Limburg; together they won 20 world championships.

- Outdoor recreation. walking or biking through the local nature areas.[16]

Pukkelpop music festival

Pukkelpop music festival Religion and folklore: Processions

Religion and folklore: Processions

Biking road alongside Meuse river

Biking road alongside Meuse river

Sports

Like the rest of Belgium, association football (soccer) and cycling, including cyclocross, are dominant sports, and tennis has gained a high prominence. Limburg is also home to Limburg United, one of the country's top professional basketball teams. The team plays its home games in the Sporthal Alverberg.

Sights

- Bokrijk open-air museum near Genk.

- High Kempen National Park.

- Racing circuit Terlaemen in Zolder, where apart from many Formula One and other car races also two world championships in bicycle racing have been held.

- A considerable number of castles and other historic properties[17]

The Abbey of Hocht at Lanaken

The Abbey of Hocht at Lanaken Royal Atheneum Hasselt

Royal Atheneum Hasselt Altembrouck castle at Gravenvoeren

Altembrouck castle at Gravenvoeren Duras castle Sint-Truiden

Duras castle Sint-Truiden Site at Tongeren near the "Perroen"

Site at Tongeren near the "Perroen"

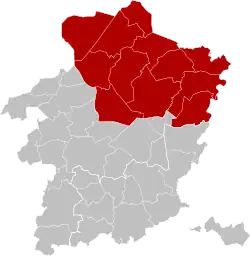

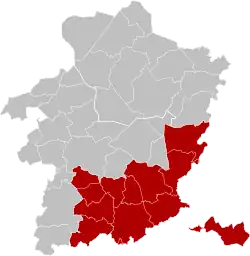

Administrative divisions

Municipalities

|

|

|

Judicial cantons

Hasselt

Hasselt Tongeren

Tongeren

Governors since the Second World War

The first governor of united Limburg (including the province of Limburg in the Netherlands) was Charles de Brouckère, from 1815, after the Battle of Waterloo until 1828. He was followed by Maximilien de Beeckman who governed the united province until 1830, when the Belgian revolution began and division of Limburg began, first with the separation of Maastricht. The splitting of Dutch and Belgian Limburg was completed by 1839.

There were also breaks in the sequence of governors in the First World War and at the end of the Second World War. The following list contains all governors of the province of Limburg since the Second World War.[18]

- Herman Reynders, governor of Limburg from 5 October 2009 until present (°1958)

- Steve Stevaert, governor of Limburg from 1 June 2005 until 15 June 2009 (°1954 – +2015)

- Hilde Houben-Bertrand, governor of Limburg from 1995 until 2005 (° 1940)

- Harry Vandermeulen, governor of the king from 1978 until 1995 (°1928)

- Louis Roppe, governor of the king from 1950 until 1978 (°1914 – +1982)

Towns in Limburg

Notable Limburgians

- Ambiorix (1st century B.C.) – Leader of the Gaulish Eburones against Julius Caesar.

- Frieda Brepoels, (1955) – Politician

- Robert Cailliau, (1947) – Co-inventor of the World Wide Web, together with Tim Berners-Lee.

- Willy Claes, (1938) – Politician; former Secretary General of NATO.

- Ingrid Daubechies, – (1954) Physicist and mathematician.

- Neel Doff, (1858–1942) – Writer.

- Jan van Eyck, (ca.1390–1441) – Flemish painter.

- Adrien de Gerlache, (1866–1934) – Former Antarctica explorer.

- Lambert of Maastricht, – Early Christian saint.

- St Servatius, – Early Christian saint.

- Barthélémy de Theux de Meylandt, (1794–1874) – Politician; former Prime Minister.

- Hendrik van Veldeke, – First writer from the Low Countries known by name (c. 1140-c. 1190).

Sports & Entertainment

- Ingrid Berghmans (1961) – Former judo world champion

- Kim Clijsters (1983) – Tennis player

- Miel Cools (1935) – Singer nl:Miel Cools

- Jos Daerden (1954) (former football player and coach)

- Lisa del Bo (1961) – Singer

- Nico Dewalque (1945) – Former soccer player

- Harry Everts (1952) – Former (4 time) motocross world champion

- Stefan Everts (1972) – Former (10 time) motocross world champion

- Eric Geboers (1962) – Former (5 time) motocross world champion

- Eric Gerets (1954) – Former soccer player

- Karel Lismont (1949) – Former athlete

- Jacky Martens (1963) – Former (1 time) motocross world champion

- Wilfried Nelissen (1970) – Former road racing cyclist~

- Luc Nilis (1967) – Former soccer player

- Guy Nulens (1957) – Former cyclist nl:Guy Nulens

- Odilon Polleunis (1943) – Former soccer player

- Axelle Red (real name Fabienne Demal (1968) – Singer-songwriter

- Kate Ryan (real name Katrien Verbeeck) (1980) – Singer

- Léon Semmeling (1940)- Former soccer player

- Steven Van Broeckhoven (1985) – Professional Freestyle Windsurfer

- Ingrid Vandebosch (1970) – Model and actress, married to NASCAR driver Jeff Gordon

- Eric Vanderaerden (1962) – Former cyclist

- Max Verstappen (1997) – Racing driver

- Jef Vliers (1932–1994), (football player and coach)

- Dana Winner (real name Chantal Vanlee) (1965) – Singer

- Jelle Vossen (1989) – Football Player

- Thibaut Courtois (1992) – Football Player

- Simon Mignolet (1988) – Football Player

See also

- Limburgish language

- Governor of Limburg

- Limburg (Netherlands), a province in southeastern Netherlands.

- Hesbaye

- CIPAL

- Campine

- Limburg Science Park

References

- "Be.STAT".

- "Structuur van de bevolking | Statbel".

- "EU regions by GDP, Eurostat". Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab".

- "Structuur van de bevolking | Statbel".

- Athenaeus, Deipnosophists, Book 4 reports the description of Poseidonius.

- Wightman (1985:104)

- Wightman (1985:202)

- "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- Tourism Limburg website

- National Park "Hoge Kempen" website

- in 1901, black coal was discovered in the Kempens steenkoolbekken; six mines closed between 1987 and 1992

- www.cordacampus.com

- PDF on official site Province saying on page 3 that Catholicism is the biggest relion in limburg

- Site showing list of typical so called "fair couses" held 2015 in Limburg Belgium

- Page on official site Province about this kind of subjects

- "List of castles in Limburg" on NlWp

- (Dutch) Gouverneurs van 1815 tot nu, limburg.be

Works cited

- Wightman, Edith Mary (1985). Gallia Belgica. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05297-0. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

General references

- Alberts, Wybe Jappe (1972). Geschiedenis van de beide Limburgen: Tot 1632 (in Dutch). Van Gorcum. ISBN 978-90-232-0999-7. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

External links

- Official website (in Dutch)