Liminality

In anthropology, liminality (from Latin līmen 'a threshold')[1] is the quality of ambiguity or disorientation that occurs in the middle stage of a rite of passage, when participants no longer hold their pre-ritual status but have not yet begun the transition to the status they will hold when the rite is complete.[2] During a rite's liminal stage, participants "stand at the threshold"[3] between their previous way of structuring their identity, time, or community, and a new way (which completing the rite establishes).

| Part of a series on |

| Anthropology of religion |

|---|

|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

The concept of liminality was first developed in the early twentieth century by folklorist Arnold van Gennep and later taken up by Victor Turner.[4] More recently, usage of the term has broadened to describe political and cultural change as well as rites.[5][6] During liminal periods of all kinds, social hierarchies may be reversed or temporarily dissolved, continuity of tradition may become uncertain, and future outcomes once taken for granted may be thrown into doubt.[7] The dissolution of order during liminality creates a fluid, malleable situation that enables new institutions and customs to become established.[8] The term has also passed into popular usage and has been expanded to include liminoid experiences that are more relevant to post-industrial society.[9]

Rites of passage

Arnold van Gennep

Van Gennep, who coined the term liminality, published in 1909 his Rites de Passage, a work that explores and develops the concept of liminality in the context of rites in small-scale societies.[10] Van Gennep began his book by identifying the various categories of rites. He distinguished between those that result in a change of status for an individual or social group, and those that signify transitions in the passage of time. In doing so, he placed a particular emphasis on rites of passage, and claimed that "such rituals marking, helping, or celebrating individual or collective passages through the cycle of life or of nature exist in every culture, and share a specific three-fold sequential structure".[8]

This three-fold structure, as established by van Gennep, is made up of the following components:[10]

- preliminal rites (or rites of separation): This stage involves a metaphorical "death", as the initiate is forced to leave something behind by breaking with previous practices and routines.

- liminal rites (or transition rites): Two characteristics are essential to these rites. First, the rite "must follow a strictly prescribed sequence, where everybody knows what to do and how".[8] Second, everything must be done "under the authority of a master of ceremonies".[8] The destructive nature of this rite allows for considerable changes to be made to the identity of the initiate. This middle stage (when the transition takes place) "implies an actual passing through the threshold that marks the boundary between two phases, and the term 'liminality' was introduced in order to characterize this passage."[8]

- postliminal rites (or rites of incorporation): During this stage, the initiate is re-incorporated into society with a new identity, as a "new" being.

Turner confirmed his nomenclature for "the three phases of passage from one culturally defined state or status to another...preliminal, liminal, and postliminal".[11]

Beyond this structural template, Van Gennep also suggested four categories of rites that emerge as universal across cultures and societies. He suggested that there are four types of social rites of passage that are replicable and recognizable among many ethnographic populations.[12] They include:

- Passage of people from one status to another, initiation ceremonies in which an outsider is brought into the group. This includes marriage and initiation ceremonies that move one from the status of an outsider to an insider.

- Passage from one place to another, such as moving houses, moving to a new city, etc.

- Passage from one situation to another: beginning university, starting a new job, and graduating high school or university.

- Passage of time such as New Year celebrations and birthdays.[12]

Van Gennep considered rites of initiation to be the most typical rite. To gain a better understanding of "tripartite structure" of liminal situations, one can look at a specific rite of initiation: the initiation of youngsters into adulthood, which Turner considered the most typical rite. In such rites of passage, the experience is highly structured. The first phase (the rite of separation) requires the child to go through a separation from his family; this involves his/her "death" as a child, as childhood is effectively left behind. In the second stage, initiands (between childhood and adulthood) must pass a "test" to prove they are ready for adulthood. If they succeed, the third stage (incorporation) involves a celebration of the "new birth" of the adult and a welcoming of that being back into society.

By constructing this three-part sequence, van Gennep identified a pattern he believed was inherent in all ritual passages. By suggesting that such a sequence is universal (meaning that all societies use rites to demarcate transitions), van Gennep made an important claim (one that not many anthropologists make, as they generally tend to demonstrate cultural diversity while shying away from universality).[12]

An anthropological rite, especially a rite of passage, involves some change to the participants, especially their social status.;[13] and in 'the first phase (of separation) comprises symbolic behaviour signifying the detachment of the individual...from an earlier fixed point in the social structure.[14] Their status thus becomes liminal. In such a liminal situation, "the initiands live outside their normal environment and are brought to question their self and the existing social order through a series of rituals that often involve acts of pain: the initiands come to feel nameless, spatio-temporally dislocated and socially unstructured".[15] In this sense, liminal periods are "destructive" as well as "constructive", meaning that "the formative experiences during liminality will prepare the initiand (and his/her cohort) to occupy a new social role or status, made public during the reintegration rituals".[15]

Victor Turner

Turner, who is considered to have "re-discovered the importance of liminality", first came across van Gennep's work in 1963.[6] In 1967 he published his book The Forest of Symbols, which included an essay entitled Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites of Passage. Within the works of Turner, liminality began to wander away from its narrow application to ritual passages in small-scale societies.[6] In the various works he completed while conducting his fieldwork amongst the Ndembu in Zambia, he made numerous connections between tribal and non-tribal societies, "sensing that what he argued for the Ndembu had relevance far beyond the specific ethnographic context".[6] He became aware that liminality "...served not only to identify the importance of in-between periods, but also to understand the human reactions to liminal experiences: the way liminality shaped personality, the sudden foregrounding of agency, and the sometimes dramatic tying together of thought and experience".[6]

'The attributes of liminality or of liminal personae ("threshold people") are necessarily ambiguous'.[16] One's sense of identity dissolves to some extent, bringing about disorientation, but also the possibility of new perspectives. Turner posits that, if liminality is regarded as a time and place of withdrawal from normal modes of social action, it potentially can be seen as a period of scrutiny for central values and axioms of the culture where it occurs.[17]—one where normal limits to thought, self-understanding, and behavior are undone. In such situations, "the very structure of society [is] temporarily suspended"[8]

'According to Turner, all liminality must eventually dissolve, for it is a state of great intensity that cannot exist very long without some sort of structure to stabilize it...either the individual returns to the surrounding social structure...or else liminal communities develop their own internal social structure, a condition Turner calls "normative communitas"'.[18]

Turner also worked on the idea of communitas, the feeling of camaraderie associated among a group experiencing the same liminal experience or rite.[19] Turner defined three distinct and not always sequential forms of communitas, which he describes as "that 'antistructural' state at stake in the liminal phase of ritual forms."[19] The first, spontaneous communitas, is described as "a direct, immediate, and total confrontation of human identities" in which those involved share a feeling of synchronicity and a total immersion into one fluid event.[19] The second form, ideological communitas, which aims at interrupting spontaneous communitas through some type of intervention which would result in the formation of a utopian society in which all actions would be carried out at the level of spontaneous communitas.[19] The third, normative communitas, deals with a group of society attempting to grow relationships and support spontaneous communitas on a relatively permanent basis, subjecting it to laws of society and "denaturing the grace" of the accepted form of camaraderie.[19]

The work of Victor Turner has vital significance in turning attention to this concept introduced by Arnold van Gennep. However, Turner's approach to liminality has two major shortcomings: First, Turner was keen to limit the meaning of the concept to the concrete settings of small-scale tribal societies, preferring the neologism "liminoid" coined by him to analyse certain features of the modern world. However, Agnes Horvath (2013) argues that the term can and should be applied to concrete historical events as offering a vital means for historical and sociological understanding. Second, Turner attributed a rather univocally positive connotation to liminal situations, as ways of renewal when liminal situations can be periods of uncertainty, anguish, even existential fear: a facing of the abyss in void.[20]

Types

Liminality has both spatial and temporal dimensions, and can be applied to a variety of subjects: individuals, larger groups (cohorts or villages), whole societies, and possibly even entire civilizations.[6] The following chart summarizes the different dimensions and subjects of liminal experiences, and also provides the main characteristics and key examples of each category.[6]

| Individual | Group | Society | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moment |

|

|

|

| Period |

|

|

|

| Epoch (or life-span duration) |

|

|

|

Another significant variable is "scale," or the "degree" to which an individual or group experiences liminality.[6] In other words, "there are degrees of liminality, and…the degree depends on the extent to which the liminal experience can be weighed against persisting structures."[6] When the spatial and temporal are both affected, the intensity of the liminal experience increases and so-called "pure liminality" is approached.[6]

In large-scale societies

The concept of a liminal situation can also be applied to entire societies that are going through a crisis or a "collapse of order".[6] Philosopher Karl Jaspers made a significant contribution to this idea through his concept of the "axial age", which was "an in-between period between two structured world-views and between two rounds of empire building; it was an age of creativity where "man asked radical questions", and where the "unquestioned grasp on life is loosened".[6] It was essentially a time of uncertainty which, most importantly, involved entire civilizations. Seeing as liminal periods are both destructive and constructive, the ideas and practices that emerge from these liminal historical periods are of extreme importance, as they will "tend to take on the quality of structure".[6] Events such as political or social revolutions (along with other periods of crisis) can thus be considered liminal, as they result in the complete collapse of order and can lead to significant social change.[15]

Liminality in large-scale societies differs significantly from liminality found in ritual passages in small-scale societies. One primary characteristic of liminality (as defined van Gennep and Turner) is that there is a way in as well as a way out.[6] In ritual passages, "members of the society are themselves aware of the liminal state: they know that they will leave it sooner or later, and have 'ceremony masters' to guide them through the rituals".[6] However, in those liminal periods that affect society as a whole, the future (what comes after the liminal period) is completely unknown, and there is no "ceremony master" who has gone through the process before and that can lead people out of it.[6] In such cases, liminal situations can become dangerous. They allow for the emergence of "self-proclaimed ceremony masters", that assume leadership positions and attempt to "[perpetuate] liminality and by emptying the liminal moment of real creativity, [turn] it into a scene of mimetic rivalry".[6]

Depth psychology

Jungians have often seen the individuation process of self-realization as taking place within a liminal space. "Individuation begins with a withdrawal from normal modes of socialisation, epitomized by the breakdown of the persona...liminality".[21] Thus "what Turner's concept of social liminality does for status in society, Jung [...] does for the movement of the person through the life process of individuation".[22] Individuation can be seen as a "movement through liminal space and time, from disorientation to integration [...] What takes place in the dark phase of liminality is a process of breaking down [...] in the interest of "making whole" one's meaning, purpose and sense of relatedness once more"[23] As an archetypal figure, "the trickster is a symbol of the liminal state itself, and of its permanent accessibility as a source of recreative power".[24]

Jungian-based analytical psychology is also deeply rooted in the ideas of liminality. The idea of a 'container' or 'vessel' as a key player in the ritual process of psychotherapy has been noted by many and Carl Jung's objective was to provide a space he called "a temenos, a magic circle, a vessel, in which the transformation inherent in the patient's condition would be allowed to take place."[12]

But other depth psychologies speak of a similar process. Carl Rogers describes "the 'out-of-this-world' quality that many therapists have remarked upon, a sort of trance-like feeling in the relationship that client and therapist emerge from at the end of the hour, as if from a deep well or tunnel.[25] The French talk of how the psychoanalytic setting 'opens/forges the "intermediate space," "excluded middle," or "between" that figures so importantly in Irigaray's writing".[26] Marion Milner claimed that "a temporal spatial frame also marks off the special kind of reality of a psycho-analytic session...the different kind of reality that is within it".[27]

Jungians however have perhaps been most explicit about the "need to accord space, time and place for liminal feeling"[28]—as well about the associated dangers, "two mistakes: we provide no ritual space at all in our lives [...] or we stay in it too long".[29] Indeed, Jung's psychology has itself been described as "a form of 'permanent liminality' in which there is no need to return to social structure".[30]

Examples of general usage

In rites

.jpg.webp)

In the context of rites, liminality is being artificially produced, as opposed to those situations (such as natural disasters) in which it can occur spontaneously.[6] In the simple example of a college graduation ceremony, the liminal phase can actually be extended to include the period of time between when the last assignment was finished (and graduation was assured) all the way through reception of the diploma. That no man's land represents the limbo associated with liminality. The stress of accomplishing tasks for college has been lifted, yet the individual has not moved on to a new stage in life (psychologically or physically). The result is a unique perspective on what has come before, and what may come next.

It can include the period between when a couple get engaged and their marriage or between death and burial, for which cultures may have set ritual observances. Even sexually liberal cultures may strongly disapprove of an engaged spouse having sex with another person during this time. When a marriage proposal is initiated there is a liminal stage between the question and the answer during which the social arrangements of both parties involved are subject to transformation and inversion; a sort of "life stage limbo" so to speak in that the affirmation or denial can result in multiple and diverse outcomes.

Getz[31] provides commentary on the liminal/liminoid zone when discussing the planned event experience. He refers to a liminal zone at an event as the creation of "time out of time: a special place". He notes that this liminal zone is both spatial and temporal and integral when planning a successful event (e.g. ceremony, concert, conference etc.).[32]

In time

The temporal dimension of liminality can relate to moments (sudden events), periods (weeks, months, or possibly years), and epochs (decades, generations, maybe even centuries).[6]

Examples

Twilight serves as a liminal time, between day and night—where one is "in the twilight zone, in a liminal nether region of the night".[33] The title of the television fiction series The Twilight Zone makes reference to this, describing it as "the middle ground between light and shadow, between science and superstition" in one variant of the original series' opening. The name is from an actual zone observable from space in the place where daylight or shadow advances or retreats about the Earth. Noon and, more often, midnight can be considered liminal, the first transitioning between morning and afternoon, the latter between days.

Within the years, liminal times include equinoxes when day and night have equal length, and solstices, when the increase of day or night shifts over to its decrease. This "qualitative bounding of quantitatively unbounded phenomena"[34] marks the cyclical changes of seasons throughout the year. Where the quarter days are held to mark the change in seasons, they also are liminal times. New Year's Day, whatever its connection or lack of one to the astrological sky, is a liminal time. Customs such as fortune-telling take advantage of this liminal state. In a number of cultures, actions and events on the first day of the year can determine the year, leading to such beliefs as first-foot. Many cultures regard it as a time especially prone to hauntings by ghosts—liminal beings, neither alive nor dead.

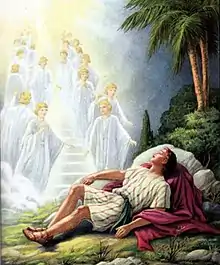

Judeo-Christian worship

Liminal existence can be located in a separated sacred space, which occupies a sacred time. Examples in the Bible include the dream of Jacob (Genesis 28:12–19) where he encounters God between heaven and earth and the instance when Isaiah meets the Lord in the temple of holiness (Isaiah 6:1–6).[35] In such a liminal space, the individual experiences the revelation of sacred knowledge where God imparts his knowledge on the person.

Worship can be understood in this context as the church community (or communitas or koinonia) enter into liminal space corporately.[35] Religious symbols and music may aid in this process described as a pilgrimage by way of prayer, song, or liturgical acts. The congregation is transformed in the liminal space and as they exit, are sent out back into the world to serve.

Of beings

Various minority groups can be considered liminal. In reality illegal immigrants (present but not "official"), and stateless people, for example, are regarded as liminal because they are "betwixt and between home and host, part of society, but sometimes never fully integrated".[6] Bisexual, intersex, and transgender people in some contemporary societies, people of mixed ethnicity, and those accused but not yet judged guilty or not guilty can also be considered to be liminal. Teenagers, being neither children nor adults, are liminal people: indeed, "for young people, liminality of this kind has become a permanent phenomenon...Postmodern liminality".[36]

The "trickster as the mythic projection of the magician—standing in the limen between the sacred realm and the profane"[37] and related archetypes embody many such contradictions as do many popular culture celebrities. The category could also hypothetically and in fiction include cyborgs, hybrids between two species, shapeshifters. One could also consider seals, crabs, shorebirds, frogs, bats, dolphins/whales and other "border animals" to be liminal: "the wild duck and swan are cases in point...intermediate creatures that combine underwater activity and the bird flight with an intermediate, terrestrial life".[38] Shamans and spiritual guides also serve as liminal beings, acting as "mediators between this and the other world; his presence is betwixt and between the human and supernatural."[39] Many believe that shamans and spiritual advisers were born into their fate, possessing a greater understanding of and connection to the natural world, and thus they often live in the margins of society, existing in a liminal state between worlds and outside of common society.[39]

In places

The spatial dimension of liminality can include specific places, larger zones or areas, or entire countries and larger regions.[6] Liminal places can range from borders and frontiers to no man's lands and disputed territories, to crossroads to perhaps airports, hotels, and bathrooms. Sociologist Eva Illouz argues that all "romantic travel enacts the three stages that characterize liminality: separation, marginalization, and reaggregation".[40]

In mythology and religion or esoteric lore liminality can include such realms as Purgatory or Da'at, which, as well as signifying liminality, some theologians deny actually existing, making them, in some cases, doubly liminal. "Between-ness" defines these spaces. For a hotel worker (an insider) or a person passing by with disinterest (a total outsider), the hotel would have a very different connotation. To a traveller staying there, the hotel would function as a liminal zone, just as "doors and windows and hallways and gates frame...the definitively liminal condition".[41]

More conventionally, springs, caves, shores, rivers, volcanic calderas—"a huge crater of an extinct volcano...[as] another symbol of transcendence"[42]—fords, passes, crossroads, bridges, and marshes are all liminal: "'edges', borders or faultlines between the legitimate and the illegitimate".[43] Oedipus met his father at the crossroads and killed him; the bluesman Robert Johnson met the devil at the crossroads, where he is said to have sold his soul.[44]

In architecture, liminal spaces are defined as "the physical spaces between one destination and the next."[45] Common examples of such spaces include hallways, airports, and streets.[46][47]

In contemporary culture viewing the nightclub experience (dancing in a nightclub) through the liminoid framework highlights the "presence or absence of opportunities for social subversion, escape from social structures, and exercising choice".[48] This allows "insights into what may be effectively improved in hedonic spaces. Enhancing the consumer experience of these liminoid aspects may heighten experiential feelings of escapism and play, thus encouraging the consumer to more freely consume".[48]

In folklore

There are a number of stories in folklore of those who could only be killed in a liminal space: In Welsh mythology, Lleu could not be killed during the day or night, nor indoors or outdoors, nor riding or walking, nor clothed or naked (and is attacked at dusk, while wrapped in a net with one foot on a cauldron and one on a goat). Likewise, in Hindu text Bhagavata Purana, Vishnu appears in a half-man half-lion form named Narasimha to destroy the demon Hiranyakashipu who has obtained the power never to be killed in day nor night, in the ground nor in the air, with weapon nor by bare hands, in a building nor outside it, by man nor beast. Narasimha kills Hiranyakashipu at dusk, across his lap, with his sharp claws, on the threshold of the palace, and as Narasimha is a god himself, the demon is killed by neither man nor beast. In the Mahabharata, Indra promises not to slay Namuci and Vritra with anything wet or dry, nor in the day or in the night, but instead kills them at dusk with foam.[49]

The classic tale of Cupid and Psyche serves as an example of the liminal in myth, exhibited through Psyche's character and the events she experiences. She is always regarded as too beautiful to be human yet not quite a goddess, establishing her liminal existence.[50] Her marriage to Death in Apuleius' version occupies two classic Van Gennep liminal rites: marriage and death.[50] Psyche resides in the liminal space of no longer being a maiden yet not quite a wife, as well as living between worlds. Beyond this, her transition to immortality to live with Cupid serves as a liminal rite of passage in which she shifts from mortal to immortal, human to goddess; when Psyche drinks the ambrosia and seals her fate, the rite is completed and the tale ends with a joyous wedding and the birth of Cupid and Psyche's daughter.[50] The characters themselves exist in liminal spaces while experiencing classic rites of passage that necessitate the crossing of thresholds into new realms of existence.

In ethnographic research

In ethnographic research, "the researcher is...in a liminal state, separated from his own culture yet not incorporated into the host culture"[51]—when he or she is both participating in the culture and observing the culture. The researcher must consider the self in relation to others and his or her positioning in the culture being studied.

In many cases, greater participation in the group being studied can lead to increased access of cultural information and greater in-group understanding of experiences within the culture. However increased participation also blurs the role of the researcher in data collection and analysis. Often a researcher that engages in fieldwork as a "participant" or "participant-observer" occupies a liminal state where he/she is a part of the culture, but also separated from the culture as a researcher. This liminal state of being betwixt and between is emotional and uncomfortable as the researcher uses self-reflexivity to interpret field observations and interviews.

Some scholars argue that ethnographers are present in their research, occupying a liminal state, regardless of their participant status. Justification for this position is that the researcher as a "human instrument" engages with his/her observations in the process of recording and analyzing the data. A researcher, often unconsciously, selects what to observe, how to record observations and how to interpret observations based on personal reference points and experiences. For example, even in selecting what observations are interesting to record, the researcher must interpret and value the data available. To explore the liminal state of the researcher in relation to the culture, self-reflexivity and awareness are important tools to reveal researcher bias and interpretation.

In higher education

For many students, the process of starting university can be seen as a liminal space.[52] Whilst many students move away from home for the first time, they often do not break their links with home, seeing the place of origin as home rather than the town where they are studying. Student orientation often includes activities that act as a rite of passage, making the start of university as a significant period. This can be reinforced by the split of town and gown, where local communities and the student body maintain different traditions and codes of behaviour. This means that many university students are no longer seen as school children, but have not yet achieved the status of independent adults. This creates an environment where risk-taking is balanced with safe spaces that allow students to try out new identities and new ways of being within a structure that provides meaning.[53]

Novels and short stories

Rant: An Oral Biography of Buster Casey by Chuck Palahniuk makes use of liminality in explaining time travel. Possession by A. S. Byatt describes how postmodern "Literary theory. Feminism...write about liminality. Thresholds. Bastions. Fortresses".[54] Each book title in The Twilight Saga speaks of a liminal period (Twilight, New Moon, Eclipse, and Breaking Dawn). In The Phantom Tollbooth (1961), Milo enters "The Lands Beyond", a liminal place (which explains its topsy-turvy nature), through a magical tollbooth. When he finishes his quest, he returns, but changed, seeing the world differently. The giver of the tollbooth is never seen and name never known, and hence, also remains liminal. Liminality is a major theme in Offshore by Penelope Fitzgerald, in which the characters live between sea and land on docked boats, becoming liminal people. Saul Bellow's "varied uses of liminality...include his Dangling Man, suspended between civilian life and the armed forces"[55] at "the onset of the dangling days".[56]

Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre follows the protagonist through different stages of life as she crosses the threshold from student to teacher to woman.[57] Her existence throughout the novel takes a liminal character. She can first be seen when she hides herself behind a large red curtain to read, closing herself off physically and existing in a paracosmic realm. At Gateshead, Jane is noted to be set apart and on the outside of the family, putting her in a liminal space in which she neither belongs nor is completely cast away.[58] Jane's existence emerges as paradoxical as she transcends commonly accepted beliefs about what it means to be a woman, orphan, child, victim, criminal, and pilgrim,[59] and she creates her own narrative as she is torn from her past and denied a certain future.[59] Faced with a series of crises, Jane's circumstances question social constructs and allow Jane to progress or to retract; this creates a narrative dynamic of structure and liminality (as coined by Turner).[59]

Karen Brooks states that Australian grunge lit books, such as Clare Mendes' Drift Street, Edward Berridge's The Lives of the Saints, and Andrew McGahan's Praise "...explor[e] the psychosocial and psychosexual limitations of young sub/urban characters in relation to the imaginary and socially constructed boundaries defining...self and other" and "opening up" new "liminal [boundary] spaces" where the concept of an abject human body can be explored.[60] Brooks states that Berridge's short stories provide "...a variety of violent, disaffected and often abject young people", characters who "...blur and often overturn" the boundaries between suburban and urban space.[60] Brooks states that the marginalized characters in The Lives of the Saints, Drift Street and Praise are able to stay in "shit creek" (an undesirable setting or situation) and "diver[t]... flows" of these "creeks", thus claiming their rough settings' "liminality" (being in a border situation or transitional setting) and their own "abjection" (having "abject bodies" with health problems, disease, etc.) as "sites of symbolic empowerment and agency".[60]

Brooks states that the story "Caravan Park" in Berridge's short story collection is an example of a story with a "liminal" setting, as it is set in a mobile home park; since mobile homes can be relocated, she states that setting a story in a mobile home "...has the potential to disrupt a range of geo-physical and psycho-social boundaries".[60] Brooks states that in Berridge's story "Bored Teenagers", the adolescents using a community drop-in centre decide to destroy its equipment and defile the space by urinating in it, thus "altering the dynamics of the place and the way" their bodies are perceived, with their destructive activities being deemed by Brooks to indicate the community centre's "loss of authority" over the teens.[60]

In-Between: Liminal Stories is a collection of ten short stories and poems that exclusively focus on liminal expressions of various themes like memory disorder, pandemic uncertainty, authoritarianism, virtual reality, border disputes, old-age anxiety, environmental issues, and gender trouble. The stories, such as "In-Between", "Cogito, Ergo Sum", "The Trap", "Monkey Bath", "DreamCatcher", "Escape to Nowhere", "A Letter to My-Self", "No Man's Land", "Whither Am I?", and "Fe/Male",[61] apart from their thematic relevance, directly and indirectly link the possibilities and potential of liminality in literature for developing characters, plots, and settings. The experiences and expressions of the in-between states of living ‘betwixt and between’ in a transitional world that intricately changes the constants and perpetuities of human life are eminent in the stories that are associated with the theoretical concepts such as permanent and temporary liminality, liminal space, liminal entity, liminoid, communitas, and anti-structure. The significance of liminality in the short stories is emphasised by conceptualising the existence of the characters as "living not here, not there – but somewhere in a space between here and there".[61]

Plays

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, a play by Tom Stoppard, takes place both in a kind of no-man's-land and the actual setting of Hamlet. "Shakespeare's play Hamlet is in several ways an essay in sustained liminality ... only via a condition of complete liminality can Hamlet finally see the way forward".[62] In the play Waiting for Godot for the entire length of the play, two men walk around restlessly on an empty stage. They alternate between hope and hopelessness. At times one forgets what they are even waiting for, and the other reminds him: "We are waiting for Godot". The identity of 'Godot' is never revealed, and perhaps the men do not know Godot's identity. The men are trying to keep up their spirits as they wander the empty stage, waiting.

Films and TV shows

The Twilight Zone (1959–2003) is a US television anthology series that explores unusual situations between reality and the paranormal. The Terminal (2004), is a US film in which the main character (Viktor Navorski) is trapped in a liminal space; since he can neither legally return to his home country Krakozhia nor enter the United States, he must remain in the airport terminal indefinitely until he finds a way out at the end of the film. In the film Waking Life, about dreams, Aklilu Gebrewold talks about liminality. Primer (2004), is a US science fiction film by Shane Carruth where the main characters set up their time travelling machine in a storage facility to ensure it will not be accidentally disturbed. The hallways of the storage facility are eerily unchanging and impersonal, in a sense depicted as outside of time, and could be considered a liminal space. When the main characters are inside the time travel box, they are clearly in temporal liminality. Yet another example comes from Hayao Miyazaki's Princess Mononoke in which the Forest Spirit can only be killed while switching between its two forms.

Photography and Internet culture

In the late 2010s, a trend of images depicting so-called "liminal spaces" surged in online art and photography communities, with the intent to convey "a sense of nostalgia, lostness, and uncertainty".[63] The subjects of these photos may not necessarily fit within the usual definition of spatial liminality (such as that of hallways, waiting areas or rest stops) but are instead defined by a forlorn atmosphere and sentiments of abandonment, decay and quietness. Additionally, it has been suggested that the liminal space phenomenon could represent a broader feeling of disorientation in modern society, explaining the usage of places that are common in childhood memories (such as playgrounds or schools) as reflective about the passage of time and the collective experience of growing older.[64]

The phenomenon gained media attention in 2019, when a short creepypasta originally posted to 4chan's /x/ board in 2019 went viral.[65] The creepypasta showed an image of a hallway with yellow carpets and wallpaper, with a caption purporting that by "noclipping out of bounds in real life", one may enter the Backrooms, an empty wasteland of corridors with nothing but "the stink of old moist carpet, the madness of mono-yellow, the endless background noise of fluorescent lights at maximum hum-buzz, and approximately six hundred million square miles of randomly segmented empty rooms to be trapped in".[66] Since then, a popular subreddit titled "liminal space", cataloguing photographs that give a "sense that something is not quite right",[67] has accrued over 500,000 followers.[68][69] A Twitter account called @SpaceLiminalBot posts many liminal space photos and it has accrued over 1.2 million followers.[70] Liminal spaces can also be found in painting and drawing, for example in paintings by Jeffery Smart.[71][72]

Research indicates that liminal spaces may appear eerie or strange because they fall into an uncanny valley of architecture and physical places.[73]

Music and other media

The 2019 surrealist puzzle game Superliminal, developed by Pillow Castle Games, explicitly incorporates liminality into its puzzles and level design.

Liminal Space is an album by American breakcore artist Xanopticon. Coil mention liminality throughout their works, most explicitly with the title of their song "Batwings (A Limnal Hymn)" (sic) from their album Musick to Play in the Dark Vol. 2. In .hack//Liminality Harald Hoerwick, the creator of the MMORPG "The World", attempted to bring the real world into the online world, creating a hazy barrier between the two worlds; a concept called "Liminality".

In the lyrics of French rock band Little Nemo's song "A Day Out of Time", the idea of liminality is indirectly explored by describing a transitional moment before the returning of "the common worries". This liminal moment is referred as timeless and, therefore, absent of aims and/or regrets.

Liminoid experiences

In 1974, Victor Turner coined the term liminoid (from the Greek word eidos, meaning "form or shape"[12]) to refer to experiences that have characteristics of liminal experiences but are optional and do not involve a resolution of a personal crisis.[2] Unlike liminal events, liminoid experiences are conditional and do not result in a change of status, but merely serve as transitional moments in time.[2] The liminal is part of society, an aspect of social or religious rites, while the liminoid is a break from society, part of "play" or "playing". With the rise in industrialization and the emergence of leisure as an acceptable form of play separate from work, liminoid experiences have become much more common than liminal rites.[2] In these modern societies, rites are diminished and "forged the concept of 'liminoid' rituals for analogous but secular phenomena" such as attending rock concerts and other[74] liminoid experiences.

The fading of liminal stages in exchange for liminoid experiences is marked by the shift in culture from tribal and agrarian to modern and industrial. In these societies, work and play are entirely separate whereas in more archaic societies, they are nearly indistinguishable.[2] In the past play was interwoven with the nature of work as symbolic gestures and rites in order to promote fertility, abundance, and the passage of certain liminal phases; thus, work and play are inseparable and often dependent on social rites.[2] Examples of this include Cherokee and Mayan riddles, trickster tales, sacred ball games, and joking relationships which serve holy purposes of work in liminal situations while retaining the element of playfulness.[2]

Ritual and myth were, in the past, exclusively connected to collective work that served holy and often symbolic purposes; liminal rites were held in the form of coming-of-age ceremonies, celebrations of seasons, and more. Industrialization cut the cord between work and the sacred, putting "work" and "play" in separate boxes that rarely, if ever, intersected.[2] In a famous essay regarding the shift from liminal to liminoid in industrial society, Turner offers a twofold explanation of this sect. First, society began to move away from activities concerning collective ritual obligations, placing more emphasis on the individual than the community; this led to more choice in activities, with many such as work and leisure becoming optional. Second, the work done to earn a living became entirely separate from his or her other activities so that it is "no longer natural, but arbitrary."[2] In simpler terms, the industrial revolution brought about free time that had not existed in past societies and created space for liminoid experiences to exist.[2]

Sports

Sporting events such as the Olympics, NFL football games, and hockey matches are forms of liminoid experiences. They are optional activities of leisure that place both the spectator and the competitor in in-between places outside of society's norms. Sporting events also create a sense of community among fans and reinforces the collective spirit of those who take part.[19] Homecoming football games, gymnastics meets, modern baseball games, and swim meets all qualify as liminoid and follow a seasonal schedule; therefore, the flow of sports becomes cyclical and predictable, reinforcing the liminal qualities.[19]

Commercial flight

One scholar, Alexandra Murphy, has argued that airplane travel is inherently liminoid—suspended in the sky, neither here nor there and crossing thresholds of time and space, it is difficult to make sense of the experience of flying.[75] Murphy posits that flights shift our existence into a limbo space in which movement becomes an accepted set of cultural performances aimed at convincing us that air travel is a reflection of reality rather than a separation from it.[75]

See also

- Androgyny – Having both male and female characteristics

- Bardo – Buddhist concept

- Cognitive dissonance – Stress from contradictory beliefs

- Critical point (thermodynamics) – Temperature and pressure point where phase boundaries disappear

- Limbo – Theological concept

- Liminal being – Being that cannot be easily placed into a single category of existence

- Liminal deity – Gods of boundaries or transitions

- Limit situation

- Locus amoenus – Literary topos involving an idealized place of safety or comfort

- Phase transition – Physical process of transition between basic states of matter

- Transitioning (transgender) – Changing gender presentation to accord with gender identity

- Trance – Abnormal state of wakefulness or altered state of consciousness

- Entity – Something that exists in some identified universe of discourse

- Intermediate state

Citations

- "liminal", Oxford English Dictionary. Ed. J. A. Simpson and E. S. C. Weiner. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989. OED Online Oxford 23, 2007; cf. subliminal.

- Turner, Victor (July 1974). "Liminal to Liminoid, in Play, Flow, and Ritual: An Essay in Comparative Symbology". Rice Institute Pamphlet - Rice University Studies. 60 (3). hdl:1911/63159. S2CID 55545819.

- Guribye, Eugene; Lie, Birgit; Overland, Gwynyth, eds. (2014). Nordic Work with Traumatised Refugees: Do We Really Care. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-4438-6777-1.

- "Liminality and Communitas", in "The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure" (New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction Press, 2008).

- Katznelson, Ira (11 May 2021). "Measuring Liberalism, Confronting Evil: A Retrospective". Annual Review of Political Science. 24 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-042219-030219.

- Thomassen, Bjørn (2009). "The Uses and Meanings of Liminality". International Political Anthropology. 2 (1): 5–27.

- Horvath, A.; Thomassen, B.; Wydra, H. (2009). "Introduction: Liminality and Cultures of Change". International Political Anthropology. 2 (1): 3–4.

- Szakolczai, A. (2009). "Liminality and Experience: Structuring transitory situations and transformative events". International Political Anthropology. 2 (1): 141–172.

- Barfield, Thomas (1997). The Dictionary of Anthropology. p. 477.

- van Gennep, Arnold (1977). The rites of passage. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7100-8744-7. OCLC 925214175.

- Victor W. Turner, The Ritual Process (Penguin 1969) p. 155.

- Andrews, Hazel; Roberts, Les (2015). "Liminality". International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. pp. 131–137. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.12102-6. ISBN 978-0-08-097087-5.

- Victor Turner, "Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites de Passage", in The Forest of Symbols (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1967).

- Turner, Ritual p. 80

- Thomassen, Bjørn (2006). "Liminality". In Harrington, A.; Marshall, B.; Müller, H.-P. (eds.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Social Theory. London: Routledge. pp. 322–323.

- Turner Ritual p. 81

- Turner, Ritual p. 156

- Peter Homas, Jung in Context (London 1979) p. 207

- John, Graham St (2008). Victor Turner and Contemporary Cultural Performance. Berghahn Books. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-85745-037-1.

- Horvath, Agnes (2013). Modernism and Charisma. doi:10.1057/9781137277862. ISBN 978-1-349-44741-1.

- Homans 1979, 207.

- Hall, quoted in Miller and Jung 2004, 104.

- Shorter 1988, 73, 79.

- Robert Pelton in Young-Eisendrath and Dawson eds. 1997, 244

- Rogers 1961, 202.

- E. Hirsh, in Burke et al. eds. 1994, 309n

- Quoted in Casement 1997, 158.

- Shorter 1988, 79.

- Bly, 1991, 194.

- Homans 1979, 208.

- Getz 2007, 179.

- Getz 2007, 442.

- Costello 2002, 158.

- Olwig, Kenneth R (April 2005). "Liminality, Seasonality and Landscape". Landscape Research. 30 (2): 259–271. doi:10.1080/01426390500044473. S2CID 144415449.

- Carson, Timothy L (2003). Transforming Worship. Chalice Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8272-3692-9.

- Kahane 1997, 31.

- Nicholas 2009, 25.

- Joseph Henderson in Jung 1978, 153.

- Takiguchi, Naoko (1990). "Liminal Experiences of Miyako Shamans: Reading a Shaman's Diary". Asian Folklore Studies. 49 (1): 1–38. doi:10.2307/1177947. JSTOR 1177947.

- Illouz 1997, 143.

- Richard Brown in Corcoran 2002, 211.

- Joseph Henderson, in Jung 1978, 152.

- Richard Brown in Corcoran 2002, 196

- El Khoury, 2015, 217

- Asuncion, Isabel Berenguer (13 June 2020). "Living through liminal spaces". INQUIRER.net.

- Matthews, Hugh (2003). "The street as a liminal space". Children in the City. pp. 119–135. doi:10.4324/9780203167236-11. ISBN 978-0-203-16723-6.

- Huang, Wei-Jue; Xiao, Honggen; Wang, Sha (May 2018). "Airports as liminal space". Annals of Tourism Research. 70: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2018.02.003. hdl:10397/77916.

- Taheri, Babak; Gori, Keith; O’Gorman, Kevin; Hogg, Gillian; Farrington, Thomas (2 January 2016). "Experiential liminoid consumption: the case of nightclubbing". Journal of Marketing Management. 32 (1–2): 19–43. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2015.1089309. S2CID 145243798.

- "Vritra". Encyclopedia of Religion. Macmillan Reference USA/Gale Group. 2006. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- Peters, Jesse (2014). "Intra Limen: An Examination of Liminality in Apuleius' Metamorphoses and Giulio Romano's Sala di Amore e Psiche". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.840.7301.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Norris Johnson, in Robben and Sluka 2007, 76

- Heading, David; Loughlin, Eleanor (2018). "Lonergan's insight and threshold concepts: students in the liminal space" (PDF). Teaching in Higher Education. 23 (6): 657–667. doi:10.1080/13562517.2017.1414792. S2CID 149321628.

- Rutherford, Vanessa; Pickup, Ian (2015). "Negotiating Liminality in Higher Education: Formal and Informal Dimensions of the Student Experience as Facilitators of Quality". The European Higher Education Area. pp. 703–723. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0_44. ISBN 978-3-319-18767-9. S2CID 146606519.

- Byatt 1990, 505–06.

- Elsbree 1991, 66.

- Bellow 1977, 84.

- Brontë, Charlotte (1816–1855). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. 2017-11-28. doi:10.1093/odnb/9780192683120.013.3523.

- Clark, Megan (2017). "The Space In-Between: Exploring Liminality in Jane Eyre". Criterion: A Journal of Literary Criticism. 10.

- Gilead, Sarah (1987). "Liminality and Antiliminality in Charlotte Brontë's Novels: Shirley Reads Jane Eyre". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 29 (3): 302–322. JSTOR 40754831.

- Brooks, Karen (1 October 1998). "Shit Creek: Suburbia, Abjection and Subjectivity in Australian 'Grunge' Fiction". Australian Literary Studies. 18 (4): 87–99.

- Mathew, Raisun (2022). In-Between: Liminal Stories. Authorspress. ISBN 978-93-91314-04-0.

- Liebler, pp. 182–84

- "Architecture: The Cult Following Of Liminal Space". Musée Magazine. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- "How liminal spaces became the internet's latest obsession". TwoPointOne Magazine. 18 June 2021. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- S, Michael L.; al (2020-04-30). "'The Backrooms Game' Brings a Modern Creepypasta to Life [What We Play in the Shadows]". Bloody Disgusting!. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- "We will find where the Original Backrooms Photo was taken. But, we need your help. - YouTube". YouTube. 2020-10-30. Archived from the original on 2020-10-30. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- "Liminal Spaces may be the most 2020 of all trends". Earnest Pettie Online. 2020-12-31. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- "Will the mall survive COVID? Whatever happens, these artists want to capture them before they're gone | CBC Arts". CBC. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- "LiminalSpace". Reddit. Retrieved 2021-07-07.

- Pitre, Jake (2022-11-01). "The Eerie Comfort of Liminal Spaces". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- Kenyon, Nick (2022-03-02). "The Exhibition Spotlighting One Of Australia's Greatest Artists". Boss Hunting. Retrieved 2022-09-02.

- "Jeffrey Smart - 155 artworks - painting". www.wikiart.org. Retrieved 2022-09-02.

- Diel, Alexander; Lewis, Michael (1 August 2022). "Structural deviations drive an uncanny valley of physical places". Journal of Environmental Psychology. 82: 101844. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101844. S2CID 250404379.

- Illouz, Consuming p. 142

- Murphy, Alexandra G. (October 2002). "Organizational Politics of Place and Space: The Perpetual Liminoid Performance of Commercial Flight". Text and Performance Quarterly. 22 (4): 297–316. doi:10.1080/10462930208616175. S2CID 145132584.

General sources

- Barfield, Thomas J. The Dictionary of Anthropology. Oxford: Blackwell, 1997.

- Bellow, Saul. Dangling Man (Penguin 1977).

- Benzel, Rick. Inspiring Creativity: an Anthology of Powerful Insights and Practical Ideas to Guide You to Successful Creating. Playa Del Rey, CA: Creativity Coaching Association, 2005.

- Bly, Robert. Iron John (Dorset 1991).

- Burke, Carolyn, Naomi Schor, and Margaret Whitford. Engaging with Irigaray: Feminist Philosophy and Modern European Thought. New York: Columbia UP, 1994.

- Byatt, A. S. Possession; a Romance. New York: Vintage International, 1990.

- Carson, Timothy L. "Chapter Seven: Betwixt and Between, Worship and Liminal Reality." Transforming Worship. St. Louis, MO: Chalice, 2003.

- Casement, Patrick. Further Learning from the Patient (London 1997).

- Corcoran, Neil. Do You, Mr Jones?: Bob Dylan with the Poets and Professors. London: Chatto & Windus, 2002.

- Costello, Stephen J. The Pale Criminal: Psychoanalytic Perspectives. London: Karnac, 2002.

- Douglas, Mary. Implicit Meanings Essays in Anthropology. London [u.a.]: Routledge, 1984.

- Elsbree, Langdon. Ritual Passages and Narrative Structures. New York: P. Lang, 1991.

- Getz, D. 2007. Event studies: theory, research and policy for planned events. Burlington, MA:Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Girard, René. "To Double Business Bound": Essays on Literature, Mimesis, and Anthropology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1988.

- Girard, René. Violence and the Sacred. London: Athlone, 1988.

- Homans, Peter. Jung in Context: Modernity and the Making of a Psychology. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1979.

- Horvath, Agnes (November 2009). "Liminality and the Unreal Class of the Image-making Craft: An Essay on Political Alchemy". International Political Anthropology. 2 (1): 51–73.

- Horvath, Agnes; Thomassen, Bjorn (May 2008). "Mimetic Errors in Liminal Schismogenesis: On the Political Anthropology of the Trickster". 1.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Illouz, Eva. Consuming the Romantic Utopia: Love and the Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. UCP, 1997.

- Jung, C. G. Man and His Symbols. London: Picador, 1978.

- Kahane Reuven, et al., The Origins of Postmodern Youth (New York: 1997)

- Liebler, Naomi Conn. Shakespeare's Festive Tragedy: the Ritual Foundations of Genre. London: Routledge, 1995.

- Lih, Andrew. The Wikipedia Revolution: How a Bunch of Nobodies Created the World's Greatest Encyclopedia. London: Aurum, 2009.

- Mathew, Raisun (2022). In-Between: Liminal Stories. Authorspress.

- Miller, Jeffrey C., and C. G. Jung. The Transcendent Function: Jung's Model of Psychological Growth through Dialogue with the Unconscious. Albany: State University of New York, 2004.

- Nicholas, Dean Andrew. The Trickster Revisited: Deception as a Motif in the Pentatech. New York: Peter Lang, 2009.

- Oxford English Dictionary. Ed. J. A. Simpson and E. S. C. Weiner. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989. OED Online Oxford University Press. Accessed June 23, 2007; cf. subliminal.

- Quasha, George & Charles Stein. An Art of Limina: Gary Hill's Works and Writings. Barcelona: Ediciones Polígrafa, 2009. Foreword by Lynne Cooke.

- Ramanujan, A. K. Speaking of Śiva. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979.

- Robben, A. and Sluka, J. Editors, Ethnographic Fieldwork: An Anthropological Reader Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

- Rogers, Carl R. On Becoming a Person; a Therapist's View of Psychotherapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1961.

- Shorter, Bani. An Image Darkly Forming: Women and Initiation. London: Routledge, 1988.

- St John, Graham (April 2001). "Alternative Cultural Heterotopia and the Liminoid Body: Beyond Turner at ConFest". The Australian Journal of Anthropology. 12 (1): 47–66. doi:10.1111/j.1835-9310.2001.tb00062.x.

- St John, Graham (ed.) 2008. Victor Turner and Contemporary Cultural Performance Archived 2010-05-07 at the Wayback Machine. New York: Berghahn. ISBN 1-84545-462-6.

- St John, Graham (June 2013). "Aliens Are Us: Cosmic Liminality, Remixticism, and Alien ation in Psytrance". The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture. 25 (2): 186–204. doi:10.3138/jrpc.25.2.186. S2CID 194094479.

- St. John, Graham (2014). "Victor Turner". Oxford Bibliographies in Anthropology. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199766567-0074. ISBN 978-0-19-976656-7.

- John, Graham St (2015). "Liminal Being: Electronic Dance Music Cultures, Ritualization and the Case of Psytrance". The SAGE Handbook of Popular Music. pp. 243–260. doi:10.4135/9781473910362.n14. ISBN 9781446210857.

- Szakolczai, A. (2000) Reflexive Historical Sociology, London: Routledge.

- Turner, "Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites de Passage", in The Forest of Symbols Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1967

- Turner, Victor Witter. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-structure. Chicago: Aldine Pub., 1969

- Turner, Victor Witter. Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1974.

- Turner, Victor. Liminal to liminoid in play, flow, and ritual: An essay in comparative symbology. Rice University Studies 1974.

- Turner, Victor W., and Edith Turner. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture Anthropological Perspectives. New York: Columbia UP, 1978.

- Gennep, Arnold Van. The Rites of Passage. (Chicago: University of Chicago), 1960.

- Waskul, Dennis D. Net.seXXX: Readings on Sex, Pornography, and the Internet. New York: P. Lang, 2004.

- Young-Eisendrath, Polly, and Terence Dawson. The Cambridge Companion to Jung. Cambridge, Cambridgeshire: Cambridge UP, 1997.

External links

The dictionary definition of liminal at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of liminal at Wiktionary The dictionary definition of liminality at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of liminality at Wiktionary The dictionary definition of liminoid at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of liminoid at Wiktionary