Lionel Brough

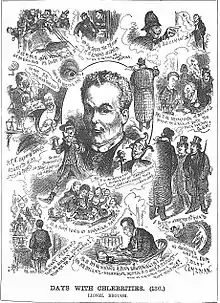

Lionel "Lal" Brough (10 March 1836 – 8 November 1909) was a British actor and comedian.[1] After beginning a journalistic career and performing as an amateur, he became a professional actor, performing mostly in Liverpool during the mid-1860s. He established his career in London as a member of the company at the new Queen's Theatre, Long Acre, in 1867, and he soon became known for his roles in Shakespeare, contemporary comedies, and classics, especially as Tony Lumpkin in She Stoops to Conquer.

In the 1870s and 1880s, Brough was one of the leading comic actors in London. Although untrained musically, he also appeared in several successful operettas in the 1880s and 1890s. He continued to contribute popular performances into the 20th century and ended his career in comedy roles with Herbert Beerbohm Tree's company.

Biography

Early years

Brough was born in Pontypool, Wales, the son of Barnabas Brough, a brewer, publican, wine merchant and later dramatist, and his wife Frances Whiteside, a poet and novelist.[2] His brothers, William[3] and Robert (father of actress Fanny Brough), were also playwrights, and his brother John Cargill Brough was a science writer. His father was briefly kidnapped by the Chartists in 1839 and was a prosecution witness at the trial of the Chartist leader John Frost, which resulted in Frost's deportation to Australia. The family was ostracised and ruined financially as a result, and they moved to Manchester in 1843.[4] Brough's first job was as an office boy at The Illustrated London News. He was then employed as assistant publisher by The Daily Telegraph and for several years at the Morning Star. At the former, he introduced to England the American system of selling the newspaper in the streets using newsboys.[5]

Brough made his stage debut at age 18 with the company of Madame Vestris to play in an extravaganza written by his brother William.[5] In 1858, he was again at the Lyceum but then left the professional stage to work at the Morning Star.[6] He performed in amateur theatricals in the early 1860s.[7] As an amateur he appeared before Queen Victoria at the Lyceum Theatre in 1860 with the Savage Club, in a burlesque of the Ali Baba story called The Forty Thieves, and was judged by the critic of The Times to have played like a practised professional.[8] This burlesque was presented as a fund-raiser for the Lancashire Famine Relief Fund.[9]

Professional career

Brough repeated The Forty Thieves in Liverpool, where Alexander Henderson, manager of the Prince of Wales Theatre in that city, was impressed enough to engage Brough for his company.[9] In his Who's Who entry, Brough recorded: "joined theatrical profession (permanently) at Prince of Wales's, Liverpool, 1863."[10] The company there included Squire Bancroft and John Hare.[5] In 1864, he performed there as Iago in Ernani opposite Lydia Thompson and Lavinia in The Miller and His Men. He also performed at other Liverpool theatres in the 1860s, including the Amphitheatre and the Alexandra, at the last of which he performed with Edward Saker, with whom he also toured.[9][11]

Brough made his London debut in 1865 in Prince Pretty Pet by his brother William at the Lyceum Theatre[7] but continued mostly in Liverpool until 1867.[6] In 1867, he joined the London company that opened the new Queen's Theatre, Long Acre, with Charles Wyndham, Henry Irving, J. L. Toole, Ellen Terry and Henrietta Hodson, in a production of Charles Reade's The Double Marriage. The Times wrote of him, "Mr Lionel Brough, an accession from the Liverpool stage, in the small part of Dard, showed the right and rare quality of humour without gag or grimace.... His appearance in other characters will be looked for with interest."[12] In The Taming of the Shrew, he was cast as Grumio.[13] He then played the serious role of uncle Ben Garner in Dearer Than Life, by H. J. Byron together with Toole, Irving and Harriet Everard, in which he was praised for his "very great power", and in which role he frequently toured.[14] This was followed by La Vivandière, W. S. Gilbert's parody of La fille du régiment, in which the same critic said that Brough "appears to understand thoroughly and remarkably for so young an actor the true principles of burlesque acting."[15] The same company presented many adaptations of the novels of Charles Dickens, including Oliver Twist in 1868, with Brough as Bumble the beadle.[16] The following year, at the St James's Theatre's revival of She Stoops to Conquer, Brough played Tony Lumpkin for almost 200 nights. Thenceforth, in the words of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, "he was the accepted representative of the character, which he played in all 777 times."[4][17] In addition to Tony Lumpkin and Ben Garner, according to Frederick Waddy, Brough's best-known early roles were Spotty in The Lancashire Lass, Sampson Burr in The Porter's Knot, Mark Meddle in London Assurance and Robin Wildbriar in Extremes. In 1873, Waddy wrote of Brough, "to his great natural humour and fun he adds a conscientious and careful study of the characters he undertakes.... He plays them with marked intelligence and appreciation, and a display of genuine humorous power and versatility not too frequently met with on the stage".[6]

In 1870, Brough was the title character in Paul Pry at the St. James's Theatre.[18] In 1871, with Mrs. John Wood, he performed in Milky White and Poll and Partner Joe.[11] In 1872, he acted as stage manager for Dion Boucicault at the Covent Garden.[6] Though not trained as a singer, Brough was recruited in 1872 to join Joseph Fell's company at the Holborn Theatre in leading roles in popular musical works including F. C. Burnand's English version of La Vie parisienne.[19] In August of the same year he appeared at Covent Garden in Dion Boucicault's fairy drama Babil and Bijou.[20] During the 1870s, Brough was resident comic lead at the Gaiety, Globe, Charing Cross and Imperial theatres. In the 1870s and 1880s he increasingly augmented his popular parts in modern works with more revivals of classic comic roles, including Tony Lumpkin again, Croaker in Oliver Goldsmith's The Good-Natured Man, Dromio of Ephesus in The Comedy of Errors and Bob Acres in The Rivals.[4] In 1878, he played opposite Lydia Thompson in burlesques at the Folly Theatre, including as King Jingo in Stars and Garters.[21] He appeared as Valentine in Mefistofele (1880) with Lizzie St Quentin in the title role, Fred Leslie as Faust and Constance Loseby as Marguerite.[22]

One of Brough's popular characters was Constable Robert Roberts, "Policeman X24", an early example of the archetypical British bobby, which he presented at concerts and benefit performances.[23] The character was a vehicle for Brough to entertain an audience with banter and comic songs. In contrast, Brough also played a serious role as a policeman in an 1884 one-act play, Off Duty, as Sergeant Ben Bloss, in which, The Morning Post said, "Mr Lionel Brough has a pathetic part, which he plays with earnestness and feeling."[24] Brough originated the role of Nick Vedder in the hit operetta Rip Van Winkle, in 1882, and played in another operetta, Nell Gwynne, in 1884. In 1885, he toured the United States with Violet Cameron.[7] In 1888, he appeared in T. Edgar Pemberton's comedy, Steeple Jack,[11] and two years later in the operetta La Cigale.[25] Brough played the comic lead, Pietro, in Gilbert and Alfred Cellier's comic opera The Mountebanks (1892).[26]

Later years

In the final phase of his career Brough was a regular member of Herbert Beerbohm Tree's company at Her Majesty's Theatre from 1894 until his death, becoming famous for his comedy roles in Shakespeare, including Sir Toby Belch in Twelfth Night, Touchstone in As You Like It, Trinculo in The Tempest, and the gardener in Richard II.[4][5] In 1895 he played Alexander McAlister, The Laird of Cockpen, in Trilby. His last appearances were in 1909 as the grave-digger in Hamlet (described by The Observer as "ideal"), Moses in The School for Scandal, and the host of the Garter Inn in The Merry Wives of Windsor.[27]

Brough encouraged all his children to become actors. His elder daughter Mary Brough ("Polly") had a long and successful career. His elder son "'Bobbie" (Robert Sydney Brough, 1868–1911) was a popular leading man when he died of complications following a throat infection; he was married to Lizzie Webster, a granddaughter of Benjamin Nottingham Webster.[28][29] Their only child, Jean Webster Brough (1900–1954), was the last theatrical member of the Brough dynasty.[30] Lionel Brough's younger daughter "Daisy" (Margaret Brough, 1870–1901) died of peritonitis, and his younger son Percy Brough (1872–1904) toured with the Brough-Boucicault Comedy Company in Australia and New Zealand but died en route from England to China.[31]

Brough died at his home, Percy Villa, in South Lambeth at the age of 73[5] and was buried at West Norwood Cemetery. The Manchester Guardian said of him in its obituary, "His power of holding his audience and obtaining his effects by the simplest means, and with an expert knowledge of their value, made his work delightful. ... In private life, Mr Brough was universally popular with a fund of anecdote which often kept the members of the Eccentric and other clubs in roars of laughter till the early hours of the morning."[32]

Notes

- "Obituary. 'Lal' Brough", Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 9 November 1909, p. 5

- "Mrs. Barnabas Brough Dead", The New York Times, 25 November 1897, p. 7

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Banerji, Nilanjana. "Brough, Lionel (1836–1909)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 25 May 2009

- The Times obituary notice, 9 November 1909, p. 11

- Waddy, Frederick. Cartoon Portraits and Biographical Sketches of Men of the Day, Tinsley brothers: London (1873), pp. 74–75

- "Lionel Brough Dead", The New York Times, 9 November 1909, p. 9

- The Times, 8 March 1860, p. 10

- Undated interview with Lionel Brough, on file in Manchestre City Library, SC 920 BRO

- "Brough, Lionel", Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, December 2007, accessed 25 May 2009

- Broadbent, R. J. Annals of the Liverpool Stage, pp. 274, 278, 308 and 316–17 Edward Howell: Liverpool (1908)

- The Times, 26 October 1867, p. 11

- The Observer, 29 December 1867, p. 6

- The Observer, 12 January 1868, p. 5

- The Observer, 26 January 1868, p. 6

- The Observer, 12 April 1868, p. 7 and The Times, 20 April 1868, p. 8

- The New York Times, in its obituary notice, gives this figure as 7777, but that would be the approximate equivalent of playing the part six times every week for 25 years

- Who's Who in the Theatre: A Biographical Record of the Contemporary Stage, John Parker (ed.), Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd (1951)

- The Observer, 21 April 1872, p. 4

- The Times, 31 August 1872, p. 8 and The Observer, 1 September 1872, p. 3

- Footnote Lights 23 November 2002 Archived 5 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 21 May 2009

- Mefistofele, Operetta Research Center, accessed 30 July 2014; and Mefistofele, Theatre Collection of the University of Kent, accessed 30 July 2014

- See, for example, The Era, 25 April 1869, p. 9; Dundee Courier, 24 May 1869, p. 1; and "Mr. G. W. Moore's Benefit", The Era, 3 May 1874, p. 11

- The Morning Post, 11 September 1884, p. 5

- Traubner, pp. 89–90

- Review of The Mountebanks from The Illustrated London News, 9 January 1892

- The Observer, 4 July 1909, p. 6

- Barranger (2004), p. 260

- Brough, Jean Webster (1952), p. 105

- "Requiem Mass", The Stage, 13 May 1954, p. 11; and Parker, p. 1611

- Brough, Jean Webster (1952), pp. 102–119

- The Manchester Guardian, 9 November 1909, p. 5

Sources

- Barranger, Milly S. (2004). Margaret Webster: A Life in the Theater. U. of Michigan Press.

- Brough, Jean Webster (1952). Prompt Copy: The Brough Story. London: Hutchinson. OCLC 1523284.

- Parker, John, ed. (1939). Who's Who in the Theatre (ninth ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons. OCLC 473894893.

- Traubner, Richard (2003). Operetta: A Theatrical History. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96641-2.