William Heirens

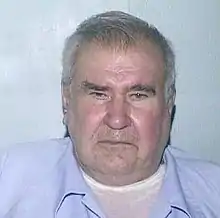

William George Heirens (November 15, 1928 – March 5, 2012) was an American criminal and possible serial killer who confessed to three murders. He was subsequently convicted of the crimes in 1946. Heirens was called the Lipstick Killer after a notorious message scrawled in lipstick at a crime scene. At the time of his death, Heirens was reputedly Illinois' longest-serving prisoner, having spent 65 years in prison.[2]

William Heirens | |

|---|---|

Heirens in 2004 | |

| Born | William George Heirens November 15, 1928 Evanston, Illinois, U.S.[1] |

| Died | March 5, 2012 (aged 83) |

| Other names | The Lipstick Killer |

| Education | University of Chicago |

| Conviction(s) | Murder (3 counts) |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment |

| Details | |

| Victims | 3 |

Span of crimes | June 5, 1945 – January 7, 1946 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | Illinois |

Date apprehended | June 26, 1946 |

He spent the later years of his sentence at the Dixon Correctional Center in Dixon, Illinois. Though he remained imprisoned until his death, Heirens had recanted his confession and claimed to be a victim of coercive interrogation and police brutality.[3]

Charles Einstein wrote a novel called The Bloody Spur about Heirens, published in 1953 which was adapted into the 1956 film While the City Sleeps by Fritz Lang.

On March 5, 2012, Heirens died at the age of 83 at the University of Illinois Medical Center from complications arising from diabetes.[3]

His story was the subject of a 2018 episode of the Investigation Discovery series A Crime to Remember.[4]

Early life

Heirens grew up in Lincolnwood, a suburb of Chicago, Illinois. He was the son of George and Margaret Heirens. George Heirens was the son of immigrants from Luxembourg and Margaret was a homemaker. His family was poor and his parents argued incessantly, leading Heirens to wander the streets to avoid hearing them. He took to crime and later claimed that he mostly stole for fun and to release tension. He never sold what he had stolen.[5]

At age 13, Heirens was arrested for carrying a loaded gun. A subsequent search of the Heirenses' home discovered a number of stolen weapons hidden in a storage shed on the roof of a nearby building, along with furs, suits, cameras, radios, and jewelry he had stolen. Heirens confessed to 11 burglaries and was sent to the Gibault School for wayward boys for several months.[5]

Soon after, he was arrested for theft and sentenced to three years at the St. Bede Academy, where he was an exceptional student. He was accepted into University of Chicago's special learning program just before his release in 1945 at age 16.[5]

To pay his expenses he worked several evenings a week as an usher and docent; he also resumed committing burglaries.[5]

A classmate remembers him as being popular with girls.[6]

Murders

Josephine Ross

On June 5, 1945, 43-year-old Josephine Ross was found dead in her Chicago apartment. She had been repeatedly stabbed, and her head was wrapped in a dress. Dark hairs were clutched in her hand.[7] No valuables were taken from the apartment.[8] Police were unable to identify a dark-haired man reportedly seen running away from the building.[7]

Frances Brown

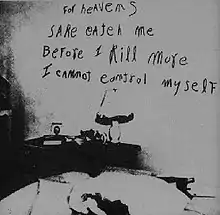

On December 10, 1945,[9] Frances Brown[10] was discovered with a knife lodged in her neck and bullet wound to the head in her apartment. Nothing was taken,[8] but a message was written in lipstick on the wall: "For heavens Sake catch me Before I kill more I cannot control myself."[11]

Police found a bloody fingerprint smudge on the doorjamb of the entrance door. A witness heard gunshots around 4 a.m., and the building's night clerk said a nervous-looking man of 35 to 40 years old, and weighing 140 pounds, got off the elevator and left around that time.[8] At one point Chicago Police said they had reason to believe the killer was a woman.[12]

Suzanne Degnan

On January 7, 1946, six-year-old Suzanne Degnan was discovered missing from her first-floor bedroom in Edgewater, Chicago. Police found a ladder outside her window, and a ransom note: "Get $20,000 ready & wait for my word. Do not notify the FBI or police. Bills are in 5's & 10's. Burn this for her safety."[8]

A man repeatedly called the Degnan residence demanding the ransom.[14]

Chicago Mayor Edward Kelly also received a note:

This is to tell you how sorry I am not to not get ole [sic] Degnan instead of his girl. Roosevelt and the OPA made their own laws. Why shouldn't I and a lot more?

At the time, there was a nationwide meatpackers' strike and the Office of Price Administration (OPA) was talking of extending rationing to dairy products. Degnan was a senior OPA executive recently transferred to Chicago. Another executive of the OPA had been recently assigned armed guards after receiving threats against his children and, in Chicago, a man involved with black market meat had recently been murdered by decapitation. Police considered the possibility the Degnan killer was a meat packer.[15]

Acting on an anonymous tip, police discovered Degnan's head in a sewer a block from the Degnan residence, her right leg in a catch basin, her torso in another storm drain, and her left leg in another drain. Her arms were found a month later in another sewer.[14] Blood was found in the drains of laundry tubs in the basement laundry room of a nearby apartment building.[16][17]

Police questioned hundreds of people, gave polygraph examinations to about 170, and several times claimed to have captured the killer, though all were eventually released.

Witnesses

The coroner fixed the time of death at between 12:30 and 1:00 a.m. and stated that a very sharp knife had been used to expertly dismember the body. A basement laundry room near the Degnans' home was located in which it appeared that Degnan had been dismembered, though it was determined that she was already dead when she was taken there. A coroner's expert stated that the killer was "either a man who worked in a profession that required the study of anatomy or one with a background in dissection...not even the average doctor could be as skillful, it had to be a meat cutter"; the coroner added that it was a "very clean job with absolutely no signs of hacking."[18]

Hector Verburgh arrest

65-year-old Hector Verburgh, a janitor in the building where Degnan lived, was arrested and treated as the suspect. Police told the press "This is the man," despite discrepancies between Verburgh's profile and the one that was developed by them as to what kind of skills the killer had, including him having surgical knowledge or at least being a butcher.[19] Police cited such evidence as Verburgh frequenting the so-called "Murder Room," and the grimy state of the ransom note suggested it was written by a dirty hand such as that of a janitor. The police pressured Verburgh's wife to implicate her husband in the murder.[20]

Police held Verburgh for 48 hours of questionings and beatings that severely injured him, including a separated shoulder.[8] Throughout, Verburgh denied involvement in the murder.[16] Verburgh's Janitor Union lawyer got Verburgh released on a writ of habeas corpus. Verburgh said of the experience:

Oh, they hanged me up, they blindfolded me ... I can't put up my arms; they are sore. They had handcuffs on me for hours and hours. They threw me in the cell and blindfolded me. They handcuffed my hands behind my back and pulled me up on bars until my toes touched the floor. I no eat. I go to the hospital. Oh, I am so sick. Any more and I would have confessed to anything.[19]

Verburgh spent ten days in the hospital.[8] It was determined that Verburgh, a Belgian immigrant, couldn't write English well enough even by the crude standards of the ransom note itself for him to have written it. He successfully sued the Chicago Police Department for $15,000; his wife received $5,000.[8][16]

Sidney Sherman investigation

Another notable false lead was that of Sidney Sherman, a recently discharged Marine who had served in World War II. Police had found blonde hairs in the back of the Degnan apartment building, and nearby was a wire that authorities suspected could have been used as a garrote to strangle Suzanne Degnan. Near that was a handkerchief the police suspected might have been used as a gag to keep Suzanne quiet. On the handkerchief was a laundry mark name: S. Sherman. The police hoped that perhaps the killer had erred in leaving it behind. They searched military records and discovered that a Sidney Sherman lived at the Hyde Park YMCA. The police went to question Sherman but discovered that he had vacated the residence without checking out and quit his job without picking up his last paycheck.[21]

A nationwide manhunt ensued. Sherman was found four days later in Toledo, Ohio. He explained under interrogation that he had eloped with his girlfriend and denied that the handkerchief was his. He was administered a polygraph test, which he passed, and was later cleared.[21] The handkerchief's real owner, Airman Seymour Sherman of New York City, was eventually found. He had been out of the country when Suzanne Degnan was murdered. He had no idea how it could possibly have ended up in Chicago and the presence of the handkerchief was determined to be a coincidence.[21]

Ransom calls

After Suzanne Degnan's disappearance, the Degnan residence received phone calls demanding ransom. A local boy, Theodore Campbell, later said that another local teenager, Vincent Costello, had killed Suzanne Degnan.[22] Costello, who lived a few blocks from the Degnans, had been convicted of armed robbery at age 16 and sent to reform school. Campbell said that Costello admitted to kidnapping and killing Suzanne Degnan, and had told him (Campbell) to make the calls to the Degnans. Costello was arrested,[22] but polygraph tests indicated that neither Campbell nor Costello had knowledge of the murder.[22]

Lack of progress

In February 1946, Suzanne Degnan's arms were found by sewer workers about a half mile from her home after her remains had already been interred. By April, some 370 suspects had been questioned and cleared.[23]

By this time, the press was taking an increasingly critical tone as to how the police were handling the Degnan investigation.[23]

Another confession

Richard Russell Thomas was a nurse living in Phoenix, Arizona, having moved from Chicago. At the time of the Chicago investigation, he was imprisoned in Phoenix for molesting one of his own daughters, but he was in Chicago at the time of the Degnan murder. A handwriting expert for the Phoenix Police Department first informed Chicago authorities of the "great similarities" between Thomas' handwriting and that of the Degnan ransom note, noting that many of the phrases Thomas had used in an extortion note were similar and his medical training as a nurse matched the profile suggested by police. Although Thomas lived on the south side, he frequented a car yard directly across the street from where Suzanne Degnan's arms were found. During questioning by Chicago police, he freely admitted to killing Suzanne Degnan.[24] However, the authorities were intrigued by a promising new suspect reported to the paper the same day the Thomas development broke. A college student was caught fleeing from the scene of a burglary, brandished a gun at police and possibly tried to kill one of the pursuing policemen to escape. By this time, Thomas had recanted his confession, but the press didn't notice in light of this new lead.[25]

Arrest and questioning of Heirens

On June 26, 1946, 17-year-old William Heirens was arrested for attempted burglary.[26]

According to Heirens, he drifted into unconsciousness under questioning and was interrogated around the clock for six consecutive days, beaten, and starved.[20] He was not allowed to see his parents for four days.[20] He was also refused the opportunity to speak to a lawyer for six days.[20][27]

Two psychiatrists, Doctors Haines and Roy Grinker, gave Heirens sodium pentothal without a warrant and without Heirens' or his parents' consent, and interrogated him for three hours.[20] Under the influence of the drug, authorities claimed, Heirens spoke of an alternate personality named "George", who had actually committed the murders. Heirens claimed that he recalled little of the drug-induced interrogation and that when police asked for "George's" last name he said he couldn't remember, but that it was "a murmuring name". Police translated this to "Murman" and the media later dramatized it to "Murder Man." What Heirens actually said is in dispute, as the original transcript has disappeared. In 1952, Grinker revealed that Heirens had never implicated himself in any of the killings.

On his fifth day in custody, Heirens was given a lumbar puncture without anesthesia. Moments later, Heirens was driven to police headquarters for a polygraph test. They tried for a few minutes to administer the test, but it was rescheduled for several days later after they found him to be in too much pain to cooperate.

When the polygraph was administered, authorities, including State's Attorney William Tuohy, announced that the results were "inconclusive." On July 2, 1946, he was transferred to the Cook County Jail, where he was placed in the infirmary to recover.[20][28][29]

Heirens' first confession

After the sodium pentothal questioning but before the polygraph exam, Heirens spoke to Captain Michael Ahern. With State's Attorney William Tuohy and a stenographer at hand, Heirens offered an indirect confession, confirming his claim while under sodium pentothal that his alter-ego "George Murman" might have been responsible for the crimes.[30] That "George" (which happens to be his father's first name and Heirens' middle name) had given him the loot to hide in his dormitory room. Police hunted all over for this "George" questioning Heirens' known friends, family, and associations, but came away empty-handed.[31]

Heirens was attributed as saying while under the influence that he met "George" when he was 13 years old; that it was "George" who sent him out prowling at night, that he robbed for pleasure, and "killed like a cobra" when cornered. "George" related his secrets to Heirens.[32] Heirens allegedly claimed that he was always taking the rap for George, first for petty theft, then assault and now murder.[32] Psychologists explained at the time that, in the same way children make up imaginary friends, Heirens made up this personality to keep his antisocial feelings and actions separate from the person who could be the "average son and student, date nice girls and go to church..."[32]

Authorities were skeptical regarding Heirens' claims and suspected that he was laying the groundwork for an insanity defense, but the confession earned widespread publicity with the press transforming "Murman" to "Murder Man."

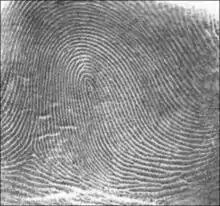

Hard evidence

While handwriting analysts did not definitively link Heirens' handwriting to the "Lipstick Message," police claimed that his fingerprints matched a print discovered at the scene of the Frances Brown murder. It was first reported as a "bloody smudge" on the doorjamb. Furthermore, a fingerprint of the left little finger also allegedly connected Heirens to the ransom note with nine points of comparison. As Heirens' nine points of comparison were loops, this could also provide a match to 65% of the population. At the time, Heirens' supporters pointed out that the FBI handbook regarding fingerprint identification required 12 points of comparison matching to have a positive identification.

On June 30, 1946, Captain Emmett Evans told newspapers that Heirens had been cleared of suspicion in the Brown murder as the fingerprint left in the apartment was not his. Twelve days later, Chief of Detectives Walter Storms confirmed that the "bloody smudge" left on the doorjamb was Heirens'.

Stolen items

Police searches (without a warrant)[20] of Heirens' residence and college dormitory found other items that earned publicity. Notably recovered was a scrapbook containing pictures of Nazi officials that belonged to a war veteran, Harry Gold, that was taken when Heirens burgled his place the night Suzanne Degnan was killed. Gold lived in the vicinity of the Degnans. This, once again, put Heirens in the circle of suspicion.[33]

Also in Heirens' possession was a stolen copy of Psychopathia Sexualis (1886), Richard von Krafft-Ebing's famous study of sexual deviance. In addition, among Heirens' belongings police discovered a stolen medical kit, but they announced that the medical instruments could not be linked to the murders. No trace of biological material such as blood, skin or hair were found on the tools. Moreover, no biological material of the victims was found on Heirens himself or any of his clothes. The medical kit tools were considered to be too fine and small to be used for dissection. Instead, Heirens had used the four-inch-long medical kit to alter the war bonds he stole.[27]

A gun was found in his possession that was linked to a shooting. A Colt Police Positive revolver had been stolen in a burglary at the apartment of Guy Rodrick on December 3, 1945. Two nights later, a bullet crashed through the closed eighth-floor apartment window of Marion Caldwell, wounding her. Heirens had that gun in his possession and, according to the Chicago Police Department, the bullet that injured Caldwell was linked through ballistics to that same gun.[33]

Eyewitness

A witness told police he saw a figure walking toward the Degnan residence with a shopping bag; he described the man as 5 feet, 9 inches tall, 170 pounds, 35 years old, and wearing a light-colored fedora and a dark overcoat, but could not make out the man's face. The witness did not recognize a photo of Heirens as showing the man he saw, but a few days later he identified Heirens in person at a court hearing.[27][34] Before the trial, inconsistencies in the witness's original statement had led many to dismiss his evidence.[18] In court it was pointed out that the witness told police that darkness had prevented his seeing the man's face, while in court he testified that he had seen Heirens walk in front of a car's headlights.[35]

Second confession

Heirens' defense attorneys "felt" he was guilty. Their task, they believed, was to save Heirens from the electric chair. Tuohy, on the other hand, was not certain he could get a conviction.[35]

The small likelihood of a successful murder prosecution of William Heirens early prompted the state's attorney's office to seek out and obtain the cooperative help of defense counsel, and through them, that of their client. All the prosecution had in the Degnan case was a partial fingerprint on the ransom note. … And it was at this stage of the investigation that defense counsel moved forward in cooperation with my office. —State's Attorney Tuohy

Heirens' lawyers pressured him to take Tuohy's plea bargain. That deal, which was the topic of that closed-door meeting with Tuohy, stated that Heirens would serve one life sentence if he confessed to the murders of Josephine Ross, Frances Brown, and Suzanne Degnan. With the help of his lawyers, he began drafting a confession using the Chicago Tribune article as a guide:

As it turned out, the Tribune article was very helpful, as it provided me with a lot of details I didn't know. My attorneys rarely changed anything outright, but I could tell by their faces if I had made a mistake. Or they would say, 'Now, Bill, is that really the way it happened?' Then I would change my story because, obviously, it went against what was known (in the Tribune).[36]

Both Heirens and his parents signed a confession.[37] The parties agreed to a date of July 30 for Heirens to make his official confession. On that date the defense went to Tuohy's office, where several reporters were assembled to ask Heirens questions and where Tuohy himself made a speech.[36][34] Heirens appeared bewildered and gave noncommittal answers to reporters' questions, which he years later blamed on Tuohy:

It was Tuohy himself. After assembling all the officials, including attorneys and policemen, he began a preamble about how long everyone had waited to get a confession from me, but, at last, the truth was going to be told. He kept emphasizing the word 'truth' and I asked him if he really wanted the truth. He assured me that he did... Now Tuohy made a big deal about hearing the truth. Now, when I was being forced to lie to save myself. It made me angry...so I told them the truth, and everyone got very upset.[36]

Tuohy withdrew the previously agreed sentence of one life term with a few minor charges, changed it to three life terms to run consecutively, and threatened Heirens with the death penalty if he went to trial.[34][37] They threatened to charge him with another murder (Estelle Carey) even though Heirens was attending the Gibault School for Wayward Boys, a boarding school in Terre Haute, Indiana, at the time.[20] Heirens' own attorneys were angry at their client for reneging on the plea bargain,[36] spurring the Chicago Tribune headline "Mute Heirens Faces Trial – Killer Spurns Mother's Fervent Plea to Talk."[37]

Tuohy announced that he would press ahead to try Heirens for the deaths of Suzanne Degnan and Frances Brown.

Heirens agreed with the new plea agreement. The public allocution was held again in Tuohy's office. This time, Heirens talked and answered questions, even reenacting parts of the murders to which he had confessed. Ahern changed his opinion and believed he was culpable when he heard how familiar Heirens was with victim Frances Brown's apartment.[37]

Heirens said later: "I confessed to save my life."

Knife

In his confession, Heirens stated that he disposed of the hunting knife with which he said he cut up Suzanne Degnan on the elevated subway tracks near the scene of the murder. The police never searched the El tracks; however, learning of this, reporters enquired with the track crew if they had found a knife. They had found it on the tracks and they kept it in the Granville station storage room. The reporters determined that the knife belonged to Guy Rodrick, the same person who had his Colt Police Positive .22 caliber gun stolen and found in Heirens' possession. On July 31, he positively identified the knife as his. Heirens acknowledged that he threw the knife there from an El train, claiming he didn't want his mother to see it.[38]

Guilty plea

Heirens took full responsibility for the three murders on August 7, 1946. The prosecution had him reenact the crime in the Degnan home in public and in front of the press.[36][39] On September 4, with Heirens' parents and the victims' families attending and Chief Justice Harold G. Ward presiding, Heirens admitted his guilt on the burglary and murder charges.[36] That night, Heirens tried to hang himself in his cell, timed to coincide during a shift change of the prison guards. He was discovered before he died. He said later that despair drove him to attempt suicide:

Everyone believed I was guilty...If I weren't alive, I felt I could avoid being adjudged guilty by the law and thereby gain some victory. But I wasn't successful even at that. ...Before I walked into the courtroom my counsel told me to just enter a plea of guilty and keep my mouth shut afterward. I didn't even have a trial...[36]

On September 5, after further evidence was written into the record and the prosecution and defense had made their closing statements, Ward formally sentenced Heirens to three life terms.[36] As Heirens waited to be transferred to Stateville Prison from the Cook County Jail, Sheriff Michael Mulcahy asked Heirens if Suzanne Degnan suffered when she was killed. Heirens answered:

I can't tell you if she suffered, Sheriff Mulcahy. I didn't kill her. Tell Mr. Degnan to please look after his other daughter, because whoever killed Suzanne is still out there.[36]

Claims of innocence

Within days of his confession in open court, Heirens denied any responsibility for the murders. Mary Jane Blanchard, daughter of murder victim Josephine Ross, was one of the first dissenters, being quoted in 1946 as saying:

I cannot believe that young Heirens murdered my mother. He just does not fit into the picture of my mother's death ... I have looked at all the things Heirens stole and there was nothing of my mother's things among them.[36]

Sodium pentothal interrogation

Heirens was subjected to an interrogation under the influence of sodium pentothal, popularly known as "truth serum." This drug was administered by psychiatrists Haines and Roy Grinker. Under its effects he allegedly stated that a second person named George Murman actually committed the killings.

This form of interrogation, which was done without a warrant and administered with neither Heirens' nor his parents' consent, is believed by most scientists today to be of dubious value in eliciting the truth, due to high suggestibility of subjects under the influence of such substances. By the 1950s, most scientists had declared the very notion of truth serums invalid, and most courts had ruled testimony gained through their use inadmissible.[40] However, when Heirens was arrested in 1946, growing scientific opinion against "truth serum" had not yet filtered down to the courts and police departments.

During Heirens' post-conviction petition in 1952, Tuohy admitted under oath that he not only knew about the sodium pentothal procedure, he had authorized it and paid Grinker $1,000.[20] The same year, Grinker revealed that Heirens never implicated himself in any of the killings.

Polygraph test

In 1946, after Heirens underwent two polygraph examinations, Tuohy declared the results inconclusive. However, John E. Reid and Fred E. Inbau published the test findings in their 1953 textbook, Lie Detection and Criminal Interrogation, which seem to contradict that assertion. According to the book, the test was not inconclusive, writing, "Murder suspect William Heirens was questioned about the killing and dismemberment of six-year old Suzanne Degnan ... On the basis of the conventional testing theory his response on the card test clearly establishes (him) as an innocent person."

Handwriting evidence

During the Degnan murder investigation, the Chicago Police Department contacted Chicago Daily News artist Frank San Hamel to examine a photograph of the ransom note. Three days after the murder, Hamel told the police and the public that he had found "hidden indentation writing" (writing impressions from a note written on an overlying piece of paper, leaving a ghostly impression). At this news, Storms broke the chain of custody and provided Hamel with the original note for him to examine directly. Since the chain of custody was broken by this action, the note was rendered useless in court no matter the result. After Heirens was arrested for the Degnan killing, Hamel reported that it implicated him. The FBI had previously issued a report on March 22, 1946, that it examined the note and declared that there was no indentation writing at all and Hamel's assertions "[...] indicated either a lack of knowledge on his part or a deliberate attempt to deceive."[20]

Even the actual handwriting on the note has been apparently discredited. Most handwriting experts, both attached to the Chicago police and independent at the time of the original investigation, believed that Heirens had no connections to either the note or the wall scribble. Charles Wilson, who was head of the Chicago Crime Detection Laboratory, declared Heirens' known handwriting exemplars obtained from Heirens' handwritten notes from college agreed with the Police Department experts who could not find any connection between Heirens, the note, and the wall message. Independent handwriting expert George W. Schwartz was brought in to give his opinion. He stated flatly that "The individual characteristics in the two writings do not compare in any respect."

A third handwriting expert, Herbert J. Walter, whose credentials included working on the Lindbergh baby kidnapping in 1932, was brought in. After examining documents written by Heirens, Walter declared that Heirens wrote the ransom note and the lipstick scrawl on the wall and attempted to disguise his handwriting. However, this was in direct contradiction to what he said several months before, at which time he said he doubted that the two writings were authored by the same person. He was quoted as saying there were "a few superficial similarities and a great many dissimilarities."

In 1996, FBI handwriting analyst David Grimes declared that Heirens' known handwriting did not match either the Degnan ransom note or the infamous "Lipstick Message,"[41] supporting the two earlier results of the original 1946 investigation and Herbert J. Walter's original January 1946 opinion. In addition, the handwritings of the two notes don't match each other.[19]

Fingerprint evidence

Among evidence suggesting Heirens' guilt is the fingerprint evidence on the Degnan ransom note and on the doorjamb of Frances Brown's bathroom door. However, suspicions on the veracity of doorjamb fingerprints found at the Brown crime scene have arisen, including charges that the police planted the fingerprint since it allegedly looks like a rolled fingerprint, the type that you would find on a police fingerprint index card.[19] Both sets of prints have come under serious question as to their validity, good faith collection and possible contamination; even the possibility of their being planted.

Ransom note fingerprints

On or around June 26, 1946, State's Attorney Tuohy announced that "there can be no doubt now" as to Heirens' guilt after the authorities linked Heirens' prints to the two prints on the ransom note. It was this assertion, unchallenged by Heirens' defense counsel at sentencing, that helped prompt him to confess to the murders with which he was charged. In a 2002 clemency petition, however, his lawyers question the validity of those prints on the ransom note due to the timing of discoveries of fingerprints on the card, the broken chain of evidence and its handling by both inexperienced law enforcement and civilians.[20]

The Degnan ransom note was first examined by the Chicago Crime Detection Laboratory, but they couldn't find any usable prints on the note. Captain Timothy O'Connor took the note to the FBI crime laboratory in Washington, D.C. on January 18, 1946, with the idea of enlisting the FBI's more sophisticated technology in finding any latent prints. The FBI subjected the note to the then advanced method of iodine fuming to raise latent prints.[20] The process was similar in execution to today's polycyanoacrylate "super glue" fuming in which Cyanoacrylate is heated to a vapor. This vapor sticks to the skin oils on the friction ridges of a latent fingerprint. The older Ninhydrin method, which is a liquid that is sprayed on paper to detect latent prints on paper is similar. The FBI were able to raise two prints which they photographed promptly because, unlike modern polycyanoacrylate, fuming prints revealed by the iodine process fade quickly. Captain O'Connor later testified at Heirens' sentencing hearing that he only saw two prints on the front of the note and did not mention the existence of any on the back.[20]

Upon his return to Chicago, he turned over the photographs of the revealed prints on the note to Sergeant Thomas Laffey, the Chicago Police Department's fingerprint expert. After his examination he stated to the press that they were "... so incomplete that it is impossible to classify them."[20] Despite checking these "incomplete" prints with everyone arrested between January 1946 and June 29, 1946, he was unable to find a match even though William Heirens was previously arrested and fingerprinted on May 1, 1946, on a weapons charge.[20] Heirens was arrested for burglary on June 26, 1946; three days later Sergeant Laffey announced a nine-point comparison match to Heirens left little finger with one of the prints. Then a match was announced between Heirens and the second print. In a news conference, State's Attorney Tuohy declared that "[...] there could be no doubt now" about the suspect's guilt but then incongruously also stated that they didn't actually have enough evidence to indict Heirens.[20]

Months after the FBI had returned the note and the photograph of the note to the Chicago police, the police announced that Laffey had discovered a palm print on the reverse side of the note also matching Heirens to ten points of comparison. No other prints were found on the note, prompting Police Chief Walter Storm to say: "This shows that Heirens was the only person to handle the note."[20]

This declaration is suspicious to some because:

- The Chicago Police couldn't find any prints originally, hence the necessity to send the ransom note to the FBI for further processing, indicating that they were incapable of finding it in the first place.

- Captain O'Connor only mentioned the two prints on the obverse side of the note and none on the reverse. Further, since both sides of the note are photographed immediately after fuming by the FBI, a third print on the reverse side would have been obvious on the note itself and at the time of the development of the photograph of the note. Yet, despite the testing occurring in mid-January, this third print wasn't discovered until early July, six months later and approximately two weeks after Heirens was arrested, despite Laffey working on the Degnan case almost exclusively for six months.[20]

- The original note was previously given to Chicago Daily News reporter Frank San Hamel the previous January (after the FBI had processed it) to examine to find any "hidden indentation writing" that Heirens supposedly left. This broke the chain of custody, making the note inadmissible as evidence in court. Additionally, any number of people, including Hamel, had compromised the integrity of any prints on the note by depositing additional prints and obscuring and corrupting the prints of the culprit.[20]

Indeed, even before the police crime lab got a chance to examine the note, Charles Wilson, the chief of the Chicago Crime Detection Laboratory, stated "When we got the Degnan note it came late after other people had photographed it and handled it."[20] In the same vein, a March 22, 1946, FBI report noted "[...] it is evident that the note has been handled considerably."[20]

These statements are in direct contradiction to Chief Walter Storm's assertion that no one else but Heirens handled the note.

Further, Laffey testified during the September 5, 1946, sentencing hearing that one more fingerprint on the reverse side of the note was linked to Heirens to ten points of comparison. He also increased the points of comparison of the palm print to Heirens from ten to the FBI standard of 12.[20]

As to the fingerprints on the front of the note that were discovered by the FBI in January 1946, Laffey only identified one and did not say it belonged to Heirens when he testified at the sentencing hearing. Only the prints not found by the FBI and allegedly discovered after Heirens' arrest were mentioned at the sentencing hearing and not the two front prints that were supposedly "indisputable" proof of Heirens' culpability.[20] They were hardly mentioned, nor were they linked to Heirens, in a court hearing in which the witnesses had to testify under oath.

As a further indication of what could be called ineffective defense by Heirens' lawyers, none of these issues were raised at the sentencing hearings and no objections were made, nor did they bring up chain-of-custody issues.[20]

Doorjamb print

A "bloody, smudged" print of an end and middle joint of a finger was found on the doorjamb of a door between the bathroom and dressing room in Frances Brown's apartment. A photograph of the print was taken, but no match was made with anything on file.[20] After Heirens was arrested on June 26, his prints were compared with the Degnan note. When Laffey claimed a match with Heirens and the prints on the Degnan note, an attempt was made to match him with the doorjamb print. It was unsuccessful, and the police declared him cleared of the Brown murder because the print at the crime scene was not his.[20] Twelve days later, however, it was declared to match Heirens' prints to 22 points of comparison, well above the FBI standard.[20]

At Heirens' sentencing, Laffey testified that the end joint of the bloody print had an eight-point comparison to Heirens' and the middle joint a six-point comparison. The middle joint didn't live up to Laffey's personal standard of seven or eight points to make a positive identification match.[20]

Another source of contention is that the Brown crime scene fingerprint has the appearance of having been rolled, which is the practice of taking a person's inked finger and rolling it on an index card, and not the smudged, bloody and unreadable print as originally reported.[19] Traditionally, after the fingertip is covered in ink from either the suspect's hand being pressed on top of an ink pad or an ink roller being run across it, the finger is placed on the card on one edge. It is rolled once from one edge to the finger's other edge to produce a large, clear print.

Heirens' attorneys did not question the veracity of the prints, however.[20]

Confession

Twenty-nine inconsistencies have been found between his confession and the known facts of the crime.[42] It has since become the understanding that the nature of these inconsistencies is a clear indicator of false confessions.[19] Some details did seem to match, like the police theory that Suzanne Degnan was dismembered by a hunting knife and Heirens confessed to throwing a hunting knife onto a section of the Chicago Subway "El" trestle near the Degnan residence. However, it was never determined scientifically that it was at least the dismemberment tool and Heirens had an alternate explanation for it. Further, it was not initially recovered by the police, but members of the press, who recovered it from the transit track gang who found it.

Alternative suspects

After the Degnan murder, but before Heirens became a suspect, Chicago police interrogated 42-year-old Richard Russell Thomas, a drifter passing through the city of Chicago at the time of Degnan's murder, found in the Maricopa County Jail in Phoenix, Arizona. Police handwriting expert Charles B. Arnold, head of the forgery detail of the Phoenix police in Thomas' hometown of Phoenix, noted similarities between the handwritten Degnan ransom note and Thomas' handwriting when Thomas wrote with his left hand,[34] and suggested that Chicago police investigate Thomas.[41]

Upon being questioned, Thomas confessed to the crime, but he was released from custody after Heirens became the prime suspect.[43] Others contend that Thomas was a strong suspect, given that:

- Thomas previously had been convicted of an attempted extortion – with a ransom note that threatened the kidnapping of a little girl.

- As previously noted, handwriting experts at the time stated that the Thomas' ransom note from his previous conviction of extortion bears similarity in both style in regard to the wording and in form of the actual structure of the letters formed, to the Degnan ransom note.[41]

- Thomas was in Chicago at the time of the Degnan murder.

- At the time he confessed to the Degnan crime, he was awaiting sentencing for molesting his daughter.[44]

- Thomas had a history of violence, including spousal abuse.[41]

- Thomas was a nurse who was known to masquerade as a surgeon. He often boasted to his friends that he was a doctor and he was known to steal surgical supplies.[41] Chicago Police had previously developed a profile of the Degnan killer as having surgical skills or being a butcher.

- He frequented a car agency near the Degnan residence. Parts of Suzanne Degnan's body were found in a sewer across the street from the car agency.[41]

- Like Heirens, he was a known burglar.

- He had confessed freely to the Degnan murder, although he later recanted.

The Chicago detectives dismissed Thomas' claims after Heirens became a suspect. Thomas died in 1974 in an Arizona prison. His prison record and most of the evidence of his interrogation regarding the Chicago murders have been lost or destroyed.[43]

George Hodel is also a prominent suspect according to the findings of his son and former LAPD officer Steve Hodel, who has attempted to link him to the Black Dahlia murder and the Zodiac Killer murders.

Aftermath

Soon after Heirens was arrested, his parents and younger brother changed their surname to "Hill." His parents divorced after his conviction.[34]

Heirens was first housed at Stateville Prison in Joliet, Illinois. He learned several trades, including electronics and television and radio repair, and at one point he had his own repair shop. Before a college education was available to prison inmates, Heirens, on February 6, 1972, became the first prisoner in Illinois history to earn a four-year college degree, receiving a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree, later earning 250 course credits by funding the cost of correspondence courses with 20 different universities from his savings. Passing courses as varied as languages, analytical geometry, data processing and tailoring, he was forbidden by authorities to take courses in physics, chemistry or celestial navigation.[35] He managed the garment factory at Stateville for five years, overseeing 350 inmates, and after transfer to Vienna Correctional Center, he set up their entire educational program. He aided other prisoners' educational progress by helping them earn their General Educational Development (GED) diplomas and becoming a "jailhouse lawyer" of sorts, helping them with their appeals.[45]

Heirens was given an institutional parole for the Degnan murder in 1965, and in 1966 he was discharged on that case and began serving his second life sentence. Although not freed, parole policies of the day meant that he was considered rehabilitated by prison authorities and that the Degnan case could no longer legally be put forward as a reason to deny parole. Based on the regulations of 1946, Heirens should have been discharged from the Brown murder in 1975 and from all remaining charges in 1983. However, in 1973 the focus moved from rehabilitation to punishment and deterrence, which blocked moves to release Heirens.[35]

In 1983, the Seventh District U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that it was unconstitutional to refuse parole on deterrence grounds to inmates convicted before 1973. Magistrate Gerald Cohn ordered Illinois to release Heirens immediately. The brother and sister of Suzanne Degnan went public, pleading with authorities to fight the ruling. Attorney General Neil Hartigan stated "Only God and Heirens know how many other women he murdered. Now a bleeding-heart do-gooder decides that Heirens is rehabilitated and should go free ... I'm going to make sure that kill-crazed animal stays where he is," a sentiment supported by the media. The Illinois Senate passed a resolution that as the "confessed murderer of Suzanne Degnan, a 6-year-old girl whom he strangled in 1946 ... that it is the opinion of the chamber that the release of William Heirens at this time would be detrimental to the best interests of the people of the state." With the support of prominent politicians, the 1983 court ruling was later reversed.[35]

In 1975, he was transferred to the minimum security Vienna Correctional Center in Vienna, Illinois, and then in 1998 upon his request[46] to the Dixon Correctional Center minimum security prison in Dixon, Illinois. He resided in the hospital ward. He suffered from diabetes, which had swollen his legs and limited his eyesight, making him have to use a wheelchair.[47] He continued with his efforts to win clemency.[48]

Petition for clemency

In 2002, Lawrence C. Marshall, et al., filed a petition on Heirens' behalf seeking clemency.[49][50] The appeal was eventually denied.

Former Los Angeles police officer Steve Hodel, who had spent 25 years on the force, met Heirens in 2003 when he was investigating the murders. He was convinced that Heirens was innocent of the crimes. "I felt compelled to write an appeal to the Illinois Prisoner Review Board stating my professional belief that Heirens is innocent."[51]

Heirens' most recent parole hearing was held on July 26, 2007. The Illinois Prisoner Review Board decision in a 14–0 vote against parole, was reflected by Board member Thomas Johnson, who stated that "God will forgive you, but the state won't".[47][52] However, the parole board also decided to revisit the issue once per year from then on.[39]

Death

After being taken to the University of Illinois Medical Center on February 26, 2012, due to complications from diabetes, Heirens died on March 5, 2012, at the age of 83.[53]

References

- Gabriel Falcon (October 24, 2009). "'Lipstick Killer' behind bars since 1946". CNN. Retrieved October 24, 2009.

- Brady-Lunny, Edith (May 30, 2009). "Gray area: Aging prison population has state looking at alternatives". Pantagraph.com. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- Lee, William (March 6, 2012). "William Heirens dead. Known as the 'Lipstick Killer'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- A Crime to Remember, Season 5 Episode 2, "The Bad Old Days", February 17, 2018.

- Martin, Douglas (March 7, 2012). "William Heirens, the 'Lipstick Killer,' Dies at 83". The New York Times. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- "The Core", Winter 2013 Supplement to the University of Chicago Magazine

- ""The Monster That Terrorized Chicago" p. 2". Archived from the original on August 19, 2009. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- Geringer, Joseph. "William Heirens: Lipstick Killer or Legal Scapegoat?: Chapter 2: 'The Atrocities". TruTV. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- "Maniac Slays Ex-WAVE, Leaves Plea In Lipstick". Toledo Blade. December 11, 1945. p. 1.

- Wilson, Colin; Pitman, Patricia (1961). Encyclopedia of Murder. London, England: Pan Books. p. 317. ASIN B0006AX7B8.

- "Heirens Linked To Murder of Wave by Print". Decatur Herald. July 13, 1946. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- "Woman Is Sought As 'Lipstick Killer'". Lewiston Daily Sun. December 15, 1945. p. 1.

- "The Daily Banner 8 January 1946 — Hoosier State Chronicles: Indiana's Digital Historic Newspaper Program". newspapers.library.in.gov. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ""The Monster That Terrorized Chicago" p. 4". Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- Rasmussen, Corroborating Evidence II, p. 51

- "The Monster That Terrorized Chicago" p. 5. Archived March 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Real Chicago: Chicago-Sun Times Photo Essay". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on March 19, 2007.

- Rasmussen, William T. (2006). Corroborating Evidence II. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Sunstone Press. pp. 61–65. ISBN 0-86534-536-8.

- Blog reproduction of Northwestern University law students 2002 article from defunct freeheirens.com site

- "html version of the Heirens Northwestern Clemency petition" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 18, 2004. Retrieved June 18, 2004.

- ""The Monster That Terrorized Chicago" p. 6". Archived from the original on October 12, 2009. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ""The Monster That Terrorized Chicago" p. 7". Archived from the original on October 12, 2009. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ""The Monster That Terrorized Chicago" p. 8". Archived from the original on October 12, 2009. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- William Heirens Archived January 11, 2015, at the Wayback Machine True crime library

- "The Monster That Terrorized Chicago" p. 9.

- ""The Monster That Terrorized Chicago" p. 16". Archived from the original on December 2, 2007. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- Geringer, Joseph. "Chapter 5: "More Clues, More Inquiries". TruTV. William Heirens: Lipstick Killer or Legal Scapegoat?. Archived from the original on August 13, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- "Real Chicago: Chicago-Sun Times Photo Essay". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on March 19, 2007.

- "photo: Heirens". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- CrimeLibrary.com/Serial Killers/Sexual Predators/William Heirens: Lipstick Killer or Legal Scapegoat

- "The Monster That Terrorized Chicago" p. 19.

- Time.com website reproduction of "Bill & George" article that appeared in Time Magazine, July 29, 1946

- ""The Monster That Terrorized Chicago" p. 17". Archived from the original on December 3, 2007. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- "Northwestern University Law April 2002 Clemency Petition" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 18, 2004. Retrieved June 18, 2004..

- Why is William Heirens still in prison? How did he get there to begin with? Chicago Reader August 24, 1989

- Geringer, Joseph. "William Heirens: Lipstick Killer or Legal Scapegoat?: Chapter 6: "Confession"". TruTV.

- ""The Monster That Terrorized Chicago" p. 20". Archived from the original on December 2, 2007. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- "The Monster That Terrorized Chicago". home.earthlink.net. Archived from the original on October 1, 2008. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- August 2, 2007 Northwestern law school article. Archived May 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Some Believe 'Truth Serums' Will Come Back" November 19, 2006 Washington Post. p. 1

- Geringer, Joseph, "William Heirens: Lipstick Killer or Legal Scapegoat?" Chapter 7: Model Prisoner URL accessed January 29, 2007

- Child in the Sewer

- December 23, 2004 Tucson Weekly article

- "Northwestern 2002 Clemency petition p. 3" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 18, 2004. Retrieved January 30, 2007.

- July 29, 2007 Sun-Times article.

- 1999 Justicedenied.org article

- Suburban Chicago News/ Courier News article.

- Tucson Weekly article

- Marshall, Lawrence C., et al., Amended Petition for Executive Clemency Archived June 18, 2004, at the Wayback Machine URL accessed January 30, 2007

- "Amended Petition for Executive Clemency" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 18, 2004. Retrieved January 30, 2007.

- Most Evil, Dutton, Steve Hodel, 2009, p. 71.

- Social Science Research Network

- "William Heirens, known as the 'Lipstick Killer,' dead". Chicago Tribune. March 6, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

Further reading

External links

- "The Monster That Terrorized Chicago" Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine