Biography in literature

When studying literature, biography and its relationship to literature is often a subject of literary criticism, and is treated in several different forms. Two scholarly approaches use biography or biographical approaches to the past as a tool for interpreting literature: literary biography and biographical criticism. Conversely, two genres of fiction rely heavily on the incorporation of biographical elements into their content: biographical fiction and autobiographical fiction.

Literary biography

A literary biography is the biographical exploration of individuals' lives merging historical facts with the conventions of narrative.[1] Biographies about artists and writers are sometimes some of the most complicated forms of biography.[2] Not only does the author of the biography have to write about the subject of the biography but also must incorporate discussion of the subject-author's literary works into the biography itself.[2][3] Literary biographers must balance the weight of commentary on the subject-author's oeuvre (complete body of works) against the biographical content to create a coherent narrative of the subject-author's live.[2] This balance is interpretively-influenced by the degree of biographical elements inherent in an author's literary works. The close relationship between writers and their work relies on ideas that connect human psychology and literature and can be examined through psychoanalytic theory.[3]

Literary biography may address subject-authors whose oeuvre contains a plethora of autobiographical information and who welcome the biographical analysis of their work. Elizabeth Longford, a biographer of Wilfrid Blunt, noted, "Writers are articulate and tend to leave eloquent source material which the biographer will be eager to use."[4] The opposite may also be the case, some authors and artists go out of their way to discourage the writing of their biographies, as was the case with Kafka, Eliot, Orwell and Auden. Auden said, "Biographies of writers whether written by others or themselves are always superfluous and usually in bad taste.... His private life is, or should be, of no concern to anybody except himself, his family and his friends."[5]

Well-received literary biographies include Richard Ellmann's James Joyce and George Painter's Marcel Proust.[2][5]

Biographical criticism

Biographical criticism is a form of literary criticism which analyzes a writer's biography to show the relationship between the author's life and their works of literature.[7] Biographical criticism is often associated with historical-biographical criticism,[8] a critical method that "sees a literary work chiefly, if not exclusively, as a reflection of its author's life and times".[9]

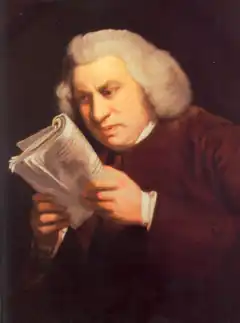

This longstanding critical method dates back at least to the Renaissance period,[10] and was employed extensively by Samuel Johnson in his Lives of the Poets (1779–81).[11]

Like any critical methodology, biographical criticism can be used with discretion and insight or employed as a superficial shortcut to understanding the literary work on its own terms through such strategies as Formalism. Hence 19th century biographical criticism came under disapproval by the so-called New Critics of the 1920s, who coined the term "biographical fallacy"[12][13] to describe criticism that neglected the imaginative genesis of literature.

Notwithstanding this critique, biographical criticism remained a significant mode of literary inquiry throughout the 20th century, particularly in studies of Charles Dickens and F. Scott Fitzgerald, among others. The method continues to be employed in the study of such authors as John Steinbeck,[7] Walt Whitman[8] and William Shakespeare.[14]Biographical fiction

Biographical fiction is a type of historical fiction that takes a historical individual and recreates elements of his or her life, while telling a fictional narrative, usually in the genres of film or the novel. The relationship between the biographical and the fictional may vary within different pieces of biographical fiction. It frequently includes selective information and self-censoring of the past. The characters are often real people or based on real people, but the need for "truthful" representation is less strict than in biography.

The various philosophies behind biographical fiction lead to different types of content. Some assert themselves as a factual narrative about the historical individual, like Gore Vidal's Lincoln. Other biographical fiction creates two parallel strands of narrative, one in the contemporary world and one focusing on the biographical history, such as Malcolm Bradbury's To the Hermitage and Michael Cunningham's The Hours. No matter what style of biographical fiction is used, the novelist usually starts the writing process with historical research.[15]

Biographical fiction has its roots in late 19th and early 20th-century novels based loosely on the lives of famous people, but without direct reference to them, such as George Meredith's Diana of the Crossways (1885) and Somerset Maugham's The Moon and Sixpence (1919). During the early part of the 20th century this became a distinct genre, with novels that were explicitly about individuals' lives.[15]

Autobiographical fiction

Autobiographical fiction, or autofiction, is fiction that incorporates the author's own experience into the narrative. It allows authors to both relay and reflect on their own experience. However, the reading of the autobiographical fiction need not always be associated with the author. Such books may be treated as distinct fictional works.[16]

Autobiographical fiction includes the thoughts and view of the narrator which describes their way of thinking.

References

- Benton, Michael (2009). Literary biography: an introduction. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-9446-4.

- Backschneider 11-13

- Karl, Frederick R. "Joseph Conrad" in Meyers (ed.) The Craft, pp 69–88

- Longford, Elizabeth "Wilfrid Scawen Blunt" of Meyers (ed.) The Craft, pp 55-68

- Meyers, Jeffrey "Introduction" in Meyers (ed.) The Craft, pp 1–8

- "Criticism".

- Benson, Jackson J. (1989). "Steinbeck: A Defense of Biographical Criticism". College Literature. 16 (2): 107–116. JSTOR 25111810.

- Knoper, Randall K. (2003). "Walt Whitman and New Biographical Criticism". College Literature. 30 (1): 161–168. doi:10.1353/lit.2003.0010. Project MUSE 39025.

- Wilfred L. Guerin, A handbook of critical approaches to literature, Edition 5, 2005, page 51, 57-61; Oxford University Press, University of Michigan

- Stuart, Duane Reed (1922). "Biographical Criticism of Vergil since the Renaissance". Studies in Philology. 19 (1): 1–30. JSTOR 4171815.

- http://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/criticism "Samuel Johnson's Lives of the Poets (1779–81) was the first thorough-going exercise in biographical criticism, the attempt to relate a writer's background and life to his works."

- Lees, Francis Noel (1967) "The Keys Are at the Palace: A Note on Criticism and Biography" pp. 135-149 In Damon, Philip (editor) (1967) Literary Criticism and Historical Understanding: Selected Papers from the English Institute Columbia University Press, New York, OCLC 390148

- Discussed extensively in Frye, Herman Northrop (1947) Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, page 326 and following, OCLC 560970612

- Schiffer, James (ed), Shakespeare's Sonnets: Critical Essays (1999),pp. 19-27, 40-43, 45, 47, 395

- Mullan, John (30 April 2005). "Heavy on the source John Mullan analyses The Master by Colm Tóibín. Week three: biographical fiction". The Guardian.

- "Melvyn Bragg on autobiographical fiction". The Sunday Times. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

Further reading

- Dale Salwak, ed. (1996). The Literary Biography. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0333626399.