Fagradalsfjall

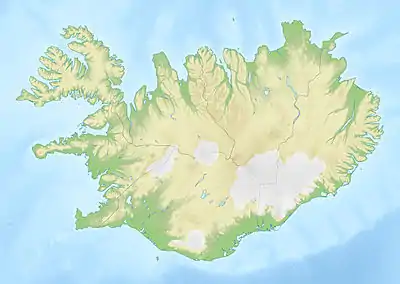

Fagradalsfjall (Icelandic: [ˈfaɣraˌtalsˌfjatl̥] ⓘ) is an active tuya volcano formed in the Last Glacial Period on the Reykjanes Peninsula,[5][6] around 40 kilometres (25 mi) from Reykjavík, Iceland.[7] Fagradalsfjall is also the name for the wider volcanic system covering an area 5 kilometres (3 mi) wide and 16 kilometres (10 mi) long between the Svartsengi [ˈsvar̥(t)sˌeiɲcɪ] and Krýsuvík systems.[8] The highest summit in this area is Langhóll [ˈlauŋkˌhoutl̥] (385 m (1,263 ft)).[1] No volcanic eruption had occurred for 815 years on the Reykjanes Peninsula until 19 March 2021 when a fissure vent appeared in Geldingadalir to the south of Fagradalsfjall mountain.[9][10] The 2021 eruption was effusive and continued emitting fresh lava sporadically until 18 September 2021.[11]

| Fagradalsfjall | |

|---|---|

_-_Fagradalsfjall.JPG.webp) Fagradalsfjall with its main peak Langhóll and Geldingadalir to the right (2012 photo) | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | Mountain: 385 m (1,263 ft) |

| Coordinates | 63°54′18″N 22°16′21″W[1] |

| Geography | |

Fagradalsfjall Iceland | |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Tuya and fissure system[2] |

| Last eruption | 10 July 2023[3][4] |

The eruption was unique among the volcanoes monitored in Iceland so far and it has been suggested that it could develop into a shield volcano.[12][13] Due to its relative ease of access from Reykjavík, the volcano has become an attraction for local people and foreign tourists.[14][15] Another eruption, very similar to the 2021 eruption, began on 3 August 2022,[16] and ceased on 21 August 2022.[17] A third eruption appeared to the north of Fagradalsfjall near Litli-Hrútur [ˈlɪhtlɪ-ˌr̥uːtʏr̥] on 10 July 2023,[4][18] and ended on 5 August 2023.[19]

Etymology

The name is a compound of the Icelandic words 'fagur' ("fair", "beautiful"), 'dalur' ("dale", "valley") and 'fjall' ("fell", "mountain"). The mountain massif is named after Fagridalur ([ˈfaɣrɪˌtaːlʏr̥], "fair dale" or "beautiful valley") which is at its northwest.[1] The 2021 lava field is named Fagradalshraun [ˈfaɣraˌtalsˌr̥œyːn].[20]

Tectonic setting

The mountain Fagradalsfjall is a volcano in areas of eruptive fissures, cones and lava fields also named Fagradalsfjall. The Fagradalsfjall fissure swarm was considered in some publications to be a branch or a secondary part of the Krýsuvík-Trölladyngja volcanic system on the Reykjanes Peninsula in southwest Iceland,[21][22] but scientists now consider Fagradalsfjall to be a separate volcanic system from Krýsuvík and it is regarded as such in some publications.[23][5] It is in a zone of active rifting at the divergent boundary between the Eurasian and North American plates. Plate spreading at the Reykjanes peninsula is highly oblique and is characterized by a superposition of left-lateral shear and extension.[24] The Krýsuvík volcanic system has been moderately active in the Holocene, with the most recent eruptive episode before the 21st century having occurred in the 12th-century CE.[25] The Fagradalsfjall mountain was formed from an eruption under the ice sheet in the Pleistocene period,[5] and it had lain dormant for 6,342 years until an eruption fissure appeared in the area in March 2021.[26]

The unrest and eruption in Fagradalsfjall are part of a larger unrest period on Reykjanes Peninsula including unrest within several volcanic systems and among others also the unrest at Þorbjörn volcano next to Svartsengi and the Blue Lagoon during the spring of 2020.[27] However, eruptions at this location were unexpected as other nearby systems on the Reykjanes Peninsula had been more active.[28]

The 2021 eruption is the first to be observed on this branch of the plate boundary in Reykjanes.[28] It appears to be different from most eruptions observed where the main volcanoes are fed by a magma chamber underneath, whose size and pressure on it determine the size and length of eruption. This eruption may be fed by a relatively narrow and long channel (~ 17 km (11 mi)) that is linked to the Earth's mantle, and the lava flow may be determined by the properties of the eruption channel.[29] However, the channel may also be linked to a deep magma reservoir located near the boundary between the crust and the mantle.[30] Some scientists believed that volcanic activities in the area may last for decades.[31]

2019 to 2021 activity and eruption

Precursors

Beginning December 2019 and into March 2021, a swarm of earthquakes, two of which reached magnitude Mw5.6, rocked the Reykjanes peninsula, sparking concerns that an eruption was imminent,[32][33][34] because the earthquakes were thought to have been triggered by dyke intrusions and magma movements under the peninsula.[35] Minor damage to homes from a 4 February 2021 magnitude 5.7 earthquake was reported.[36] In the three weeks before the eruption, more than 40,000 tremors were recorded by seismographs.[37]

Eruption fissures in Geldingadalir

On 19 March 2021, an effusive eruption started at approximately 20:45 local time in Geldingadalir ([ˈcɛltiŋkaˌtaːlɪr̥];[lower-alpha 1] the singular "Geldingadalur" [ˈcɛltiŋkaˌtaːlʏr̥] is also often used)[39] to the south of Fagradalsfjall,[9] the first known eruption on the peninsula in about 800 years.[40] Fagradalsfjall had been dormant for 6,000 years.[41][42] The eruptive activity was first announced by the Icelandic Meteorological Office at 21:40.[43] Reports stated a 600–700-metre-long (2,000–2,300 ft) fissure vent began ejecting lava,[44] which covered an area of less than 1 square kilometre (0.39 sq mi). As of the March eruptions, the lava flows posed no threat to residents, as the area is mostly uninhabited.[7]

The eruption has been called Geldingadalsgos ([ˈcɛltiŋkaˌtalsˌkɔːs] "Geldingadalur eruption").[45] On 26 March, the main eruptive vent was at 63.8889 N, 22.2704 W, on the site of a previous eruptive mound. The eruption may be a shield volcano eruption,[46] which may last for several years.[46] It could be seen from the suburbs of the capital city of Reykjavík[47] and had attracted a large number of visitors.[48] However, high levels of volcanic gases such as carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide made parts of the area inaccessible.[49]

Geldingadalir eruption near Fagradalsfjall, 24 March 2021.

Geldingadalir eruption near Fagradalsfjall, 24 March 2021. People on the slopes of Fagradalsfjall, watching the Geldingadalir eruption.

People on the slopes of Fagradalsfjall, watching the Geldingadalir eruption.- Video of eruption from helicopter.

.jpg.webp) Satellite image from 29 April 2021

Satellite image from 29 April 2021

On 13 April 2021, four new craters formed in Geldingadalir within the lava flows. The lava output which had been somewhat reduced over the last days, increased again.[50]

Eruption fissures on Fagradalsfjall

Around noon on 5 April a new fissure, variously estimated to be between about 100 and 500 metres (300 and 2,000 ft) long, opened a distance of about 1 kilometre (0.5 mi) to the north/north-east of the still-active vents at the center of the March eruption. As a precaution the area was evacuated by the coast guard.[51][52][53]

Some time later, another eruption fissure opened parallel to the first on the slopes of Fagradalsfjall.[54]

The lava production of all open eruption fissures in the whole was estimated on 5 April 2021, being around 10 m3/s (350 cu ft/s) [55][56] and is flowing into the Meradalir valleys ([ˈmɛːraˌtaːlɪr̥], "mare dales") via a steep gully.[57]

The new eruption fissures.

The new eruption fissures. The new eruption fissures to the left, the older ones to the right, seen from a helicopter, view to the east.

The new eruption fissures to the left, the older ones to the right, seen from a helicopter, view to the east.

About 36 hours later, around midnight on 6–7 April, another eruption fissure opened up. It is about 150 m (490 ft) long and about 400–450 m (1,300–1,500 ft) to the north-east of the first fissure, between the Geldingadalur fissures and the ones on the slope of the mountain.[58][59][60] Search and rescue crews observed a new depression, about 1 m (3 ft) deep there the previous day. The lava from this fissure flowed into Geldingadalur valley.[61]

Another fissure opened during the night of 10–11 April 2021 between the two open fissures on the slopes of Fagradalsfjall.[62] In total, 6 fissures had opened until the 13 April and at each fissure, activity concentrated and formed individual vents. Towards the end of April, activity at most vents, apart from Vent 5, started to decrease.[63]

By 2 May 2021, only one fissure, Vent 5 that appeared near the initial eruption site on Geldingadalir, remained active. It developed into a volcano with the occasional explosive eruptions within its crater that sometimes reached heights of hundreds of meters.[64] The rim of the volcano itself had risen to a height of 334 m (1,096 ft) above sea level by September 2021.[30] The lava flowed into the Meradalir valleys,[65] and later the Nátthagi [ˈnauhtˌhaijɪ] valley.[66]

A number of smaller openings appeared temporarily, one small vent was reported to have erupted near the main crater on 1 July.[67] On 14 August, lava spurted from what appeared to be a hole on the crater wall, and this turned out to be an independent eruption.[68] Cracks appeared on Gónhóll [ˈkouːnˌhoutl̥] that was once popular with spectators in August but no lava flowed at the site.[69] After eight and a half days of inactivity at the main volcano, lava broke through the surface in the lava field to the north of the crater in a number of places.[70]

Lava and gas output: Development of the eruption

The eruption showed distinct phases in its eruption pattern. The first phase lasted for about two weeks with continuous lava flow of around 6 m3/s (210 cu ft/s) from its first crater, the second phase also lasted around two weeks with new eruptions to the north of the first crater with variable lava flow of 5–8 m3/s (180–280 cu ft/s). This is followed by a period of two and a half months of eruption at a single crater with largely continuous and sometimes pulsating eruption and lava flow of around 12 m3/s (420 cu ft/s) lasting until the end of June. From then on until early September was a phase of fluctuating eruption with periodic strong lava flow interrupted by periods of inactivity.[71][72]

On 12 April, scientists from the University of Iceland measured the lava field's area to be 0.75 km2 (0.29 sq mi) and its volume to be 10.3 million m3 (360 million cu ft). The flow rate of the lava was 4.7 m3/s (170 cu ft/s), and sulfur dioxide, carbon dioxide and hydrogen fluoride were being emitted at 6,000, 3,000 and 8 tonnes per day (5,900, 3,000 and 7.9 long tons per day) respectively.[73]

The lava produced by the eruption shows a composition differing from historical Reykjanes lavas. This could be caused by a new batch of magma arriving from a large magma reservoir at a depth of about 17–20 km (11–12 mi) at the Moho under Reykjanes.[74][75][76]

- Examples of basaltic lava collected in late March

_1.jpg.webp)

_2.jpg.webp)

_4.jpg.webp)

Results from measurements published by University of Iceland on 26 April 2021 showed that the composition of eruption products had changed, to more closely resemble the typical Holocene basalts of Reykjanes peninsula.[77] The eruption itself also changed in character at the same time,[78] and was producing lava fountains up to 50 m (160 ft) in height on Sunday, 25 April 2021.[79] On 28 April 2021, the lava fountains from the main crater reached a height of 250 m (820 ft).[80]

The eruption pattern changed on 2 May from a continuous eruption and lava flow to a pulsating one, where periods of eruptions alternated with periods of inactivity, with each cycle lasting 10 minutes to half an hour.[81][82] The magma jets became stronger, producing lava fountains of 300 m (980 ft) in height, visible from Reykjavík,[83][84] with the highest one measured at 460 m (1,510 ft).[82] The lava jets have been explained as explosive release of ancient trapped water or magma coming in contact with groundwater.[85][86] The lava flow rate in the following weeks was also double that of the average for the first six weeks,[87] with an average lava flow rate of 12.4 m3/s (440 cu ft/s) from 18 May to 2 June.[88]

The increase in lava flow is unusual, as eruption outputs typically decrease with time. Scientists from the University of Iceland hypothesize that there is a large magma reservoir deep under the volcano, not the typical smaller magma chamber associated with these kinds of eruptions that empty over a short time.[89] From the composition of the magma sampled, they also believe that there is a discrete vent feeding the main lava flow from a depth of 17–20 kilometres (11–12 mi) from the Earth's mantle, and may be of a more primitive kind than those previously observed.[90] The channel widened in the first six weeks leading to increased lava flow.[30] The eruption may create a new shield volcano if it continues for long enough.[91] The formation of such volcano has not been studied before in real time, and this eruption can offer insights into the working of the magmatic systems.[13]

Two defensive barriers were created starting 14 May as an experiment to stop lava flowing into the Nátthagi valley where telecommunication cables are buried, and further on to the southern coastal road Suðurlandsvegur.[92] However, the lava soon flowed over the top of eastern barrier 22 May, and cascaded down to the Nátthagi.[93][94][95] Lava flowed over the western barrier on 5 June.[96] Lava flow blocked the main trail that provide access to the main viewing area on Gónhóll, first on 4 June,[97] then again early in the morning of 13 June at another location.[98] A further wall five meters high and 200 meters long was then created on 15 June in an attempt to divert lava flow away from Nátthagakriki [ˈnauhtˌhaːɣaˌkʰrɪːcɪ] with important infrastructure to its west and north.[99] A barrier of 3 to 5 m high started to be constructed on 25 June at the mouth of Nátthagi to delay the flow of the lava over the southern coastal road and properties on Ísólfsskáli [ˈiːsˌoul(f)sˌskauːlɪ], although it was expected that the lava would eventually flow over the area into the sea.[100][101] A proposal to build a bridge over the road to allow the lava flow underneath was rejected.[102]

Around three months after the volcano first erupted, the lava flow was a steady 12 m3/s (420 cu ft/s), and the lava now covered an area of more than 3 km2 (1.2 sq mi) increasing by around 60,000 m2/d (650,000 sq ft/d).[103][104] Lava had accumulated 100 m (330 ft) deep around the volcano.[105] The lava flow became continuous, which can be either above or below ground, although the eruptions also became calmer with the occasional increase in activity.[106][107] There appeared to be no direct connection between the activity at the crater and lava flow.[108] The lava flow can be tracked by helicopter or satellite, for example via radar imaging that can penetrate through the clouds and volcanic smog that had become more frequent in the area by July.[109][110]

The eruptions stayed unusually constant until 23 June, and the activity then reduced significantly on 28 June, becoming inactive for many hours,[111][112] and resuming on 29 June.[113][114] It shifted to a pattern of many hours of inactivity, for example on 1 and 4 July,[115][116] with the eruptions resuming later.[117] Lava flow from the crater ceased for 4 days from 5 July until 9 July,[118][119] when eruptions resumed, initially with a periodicity of around 10 to 15 minutes,[120] then lengthening to 3 to 4 an hour by 13 July.[121] Lava has also been observed emerging from the bottom of the volcano on 10 July with considerable amount of lava flowing into the Meradalir valleys,[120][122][123] and a section of the volcano on the northeastern side also broke off on 14 July.[124] Lava flow was estimated to be around 10 m3/s (350 cu ft/s) but averaged to 5 to 6 m3/s (180 to 210 cu ft/s) due to the periods of inactivity from late June to mid-July, half of the flow rate in May and June.[125] The periodic lull in activity continued,[126][127] with 7 to 13 hours of inactivity and similar period of eruption by late July,[128] which lengthened to a pattern of mostly around 15 hours of inactivity alternating with around 20 hours of continuous eruption in August.[129] It has been speculated that there are blockages at the top hundred metres of the eruption channel.[127] By July, this eruption had become larger than most eruptions that have ever occurred on the Reykjanes peninsula.[130] Measurement taken on 27 July indicated that the lava flow had increased again, returned to and possibly exceeding the peak level last seen in June.[131] The measurement indicated an average flow of 17–18 m3/s (600–640 cu ft/s) over 8–10 days, the highest observed thus far, but with a large margin of error.[132] After a couple of months where the lava flowed mainly into the Meradalir valleys, the lava started to flow down the Nátthagi valley again on 21 August.[133][134] The eruption by now had become the second longest in Iceland of the 21st century.[135]

The volcano stopped erupting on 2 September,[136] but lava flow resumed on 11 September, with the magma breaking through the lava field surface in several places.[137] However, the main crater channel appeared to have been blocked, and the crater was filled with lava from a source underneath the northwestern wall through a crack on the wall,[138] and lava also flowed outside the volcano through the wall.[70] The average lava flow over the past 32 days had returned to 8.5 m3/s (300 cu ft/s), and the lava field of 143 million m3 (5.0 billion cu ft) now covered an area of 4.6 km2 (1.8 sq mi).[30][139] After a period of continuous eruption, a pulsing pattern of activity last seen in April/May started on 13 September,[140] a pattern believed to be similar to what is observed in geysers where the frequency of eruption may be determined by the size of the reservoir below and how quickly it is filled up. The volcano was pulsing at a rate of around eight eruptions per hour on 14 September.[141] No lava flowed out directly from the crater, instead lava began to emerge in significant amount from outside the volcano on 15 September.[142] On 16 September 2021, after 181 days of eruption, it became the longest eruption of the 21st century in Iceland.[143] Average lava flow was 16 m3/s (570 cu ft/s) from 11 to 17 September when flow resumed, with the lava field increasing to 151 million m3 (5.3 billion cu ft) covering an area of 4.8 km2 (1.9 sq mi).[144] The eruption stopped again on 18 September, but the activity decreased unusually slowly.[145] On 18 October, the alert level was lowered from "Orange" to "Yellow" due to no lava having erupted since 18 September. The Icelandic meteorological office also stated that "it is assessed that Krýsuvík volcano is currently in a non-eruptive state. The activity might escalate again, so the situation is monitored closely".[146]

2022 eruption

On 30 July, IMO reported an intense earthquake swarm in an area close to the lava field in Geldingadalur. On 31 July, almost 3,000 earthquakes were detected. [147]

Earthquakes were reportedly felt in SW Iceland, in Reykjanesbær, Grindavík, the Capital region, and as far as Borgarnes. Several of these earthquakes were above an Mw 3, with the largest event of an Mw 4 occurring at 1403. according to the Norwegian Meteorological Agency’s automatic location system; an Mw 5.4 event was detected at 1748. Deformation models indicated magma was around 1 km below the surface at 1749 on 2 August, according to IMO. [148]

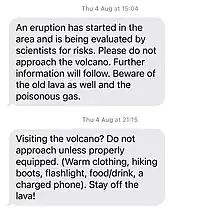

On 3 August 2022, after weeks of unrest on the Reykjanes Peninsula including over 10,000 recorded earthquakes from 30 July to 3 August with two quakes measuring over 5.0 Mw, another eruption began at Fagradalsfjall. A live stream from a camera at the site showed magma spewing from a narrow fissure vent. On 4 August the Icelandic Meteorological Office estimated it 360 meters in length. Over 1,830 people visited the volcano on the first day.[149] It erupted over a lava flow from the 2021 eruption. The Icelandic Meteorological Office initially advised people not to go near Fagradalsfjall due to the new eruption.[150][151]

Lava flows were reported traveling downslope to the NW. The flow rate was about 32 m3/s during the initial hours of the eruption, which then decreased to an average of 18 m3/s from 1700 on 3 August until 1100 on 4 August. By this time, about 1.6 million cubic meters of lava had covered an area of 0.14 km2. [152]

Iceland's Department of Civil Protection and Emergency Management stated that no lives or infrastructure were currently at risk from the eruption. Iceland's main airport, Keflavík Airport, was briefly on alert, which is a standard procedure during eruptions, though the facility did not cancel any flights.[153][154] Airplanes were prohibited from flying over the site, although some helicopters were sent in to survey the eruption.[155] The eruption was not producing large plumes, though it was likely to affect air quality and pollution in immediately surrounding areas.[156] Professor of geophysics Magnús Tumi Guðmundsson said, judging from the initial lava flow, that the eruption was likely five to ten times bigger than the 2021 eruption, but that it was not "the big one". From the nearby geomorphology, the lava was likely to flow into the Meradalir valleys.[157]

According to a news article from RUV, the length of the active fissure had decreased and the middle part of the fissure was the most active by 5 August. In addition, the number of daily earthquakes declined around the same day; strong gas-and-steam emissions were still visible. By 10 August lava was primarily erupting from a central cone and flowed ESE and NW. IMO reported that lava was mostly flowing onto the 2021 lava flow field and was filling the eastern end of the Meradalir lava through at least 16 August.[158]

There were three vents within the building cone that were visible on 10 August: the first is the largest and most centrally located vent, the second is to the left (east) of the central vent, and the third is the smallest one located to the right (west) of the central vent. Each of these vents erupted strong lava fountains rising tens to several tens of meters high during at least 10-13 August, then during 14-16 August the height of the lava fountains diminished. A smaller, secondary cone formed to the east of the main cone around 12 August. These vents fed into a large lava pond that traveled NW of the breached vent and occasionally, lava breakouts would be noted along the ponded lava. Each day during 12-16 August the primary eruptive cone continued to grow, evolving to a perched lava pond that fed the lava flows to the NW of it.[159]

The lava flow decreased around 17 August[160] and stopped on 21 August 2022. An estimated 12 million cubic meters of lava had erupted. The lava near the vent was 20-40 m thick, but flows were 5-15 m thick in the Meradalir valley, outside the crater area[161] Since then, there has been no visible activity at this site.[17]

2023 Litli-Hrútur eruption

.jpg.webp)

Seismic activity in the area increased greatly starting 4 July 2023 with over 12,000 earthquakes recorded, and following a 5.2 magnitude earthquake,[162] lava broke through the surface on 10 July 2023 near Litli-Hrútur northeast of previous eruptions.[163][164][165] This eruption was initially significantly stronger than the first two,[166][167] with initial lava flow estimated to be 10 times more than the first eruption.[168][169] Multiple eruptive fissures, originally 200m in length, stretched for over 1 km between Fagradalsfjall and Keilir,[170] significantly longer than the Meradalir eruptions.[171] Flow of lava up to 50 m3/s was reported in the first day,[172] but dropped to an average of 13 m3/s, the peak flow rate of the first eruption, within a few days.[173] The eruptions quickly reduced to a single 200m long fissure, which formed a single elongated active cone that increased in height by around 3m a day.[174]

The lava flowed in a southerly direction to meet the older lava field of Meradalir,[175][176] but the lava caused significant wildfires in the area.[177] Some lava flowed in different directions when the wall of the volcano collapsed on 19 July,[178] but it then resumed flowing southwards.[179][180] The crater rim has widened significantly, which increased the possibility of wall collapse,[181] and another rim collapse happened on 24 July.[182] Lava flow gradually slowly fall through time, down to 8 m3/s by 23 July, with most of the lava by now flowing to the east. Lava flow also reached a volume of 12.4 million cubic meters, greater in volume than the second eruption, covering an area of 1.2 km2.[183] Lava flow from the crater by now has become completely underground.[184] The lava since the beginning of the eruption has been determined to be similar to the lava from the end of the first eruption and the lava of the second eruption, indicating a link to the previous two eruptions.[185]

The latest Icelandic Institute of Earth Sciences statistics revealed on 31 July indicate a notable reduction of the effusive eruption. The estimated lava flow discharge rate during 23-31 July was measured to be about 5,0 m³/s. The previous values, detected between 18 and 23 July, signalized the discharge rate of the lava at about 9,0 m³/s, which is nearly double the drop in the rate. As of 31 July, the outpouring lava has covered an area of 1,5 km² with a volume of approx. 15,9 million m³.[186]

Lava flow reduced to 3–4 m3/s by early August, suggesting that the eruption is approaching its end.[187] With the reduced amount of lava in the crater, a smaller cone also formed within the crater.[188] Volcanic activity at the site ceased on 5 August 2023.[19] The eruption site proved very popular with tourists once more. It is estimated that almost seven hundred thousand people have visited the area since the 2021 Fagradalsfjall eruption.[189]

Risk mitigation and tourism

Due to the volcanic site's proximity to the town of Grindavík, Vogar and to a lesser extent Keflavik, Keflavik International Airport and the Greater Reykjavík Area, Iceland's Department of Civil Protection and Emergency Management has created protocols for evacuation plans of nearby settlements and in case of gas pollution and/or lava flows.[190][191][192] The large number of tourists visiting the eruption sites is also a concern to authorities, especially under-equipped tourists and those who do not heed official closures during inclement weather or new lava flows.[193][194][195]

As of the second eruption in 2022, there is little risk of lava flows blocking roads or reaching settlements, but this could change if the Meradalir valleys fill with lava or another fissure opens up in a different area.[196]

Air traffic

The eruption site is only around 20 km (12 mi) from Iceland's main international airport, Keflavik International Airport. Due to the eruption's effusive nature with little to no ash production, it is not considered a risk to air traffic. The ICAO Aviation Colour code has mostly stayed orange (ongoing eruption with low to no ash production). This has meant that no interruptions to flight traffic to and from Keflavik International Airport.[197] Icelandic Coast Guard helicopters have conducted many research and monitoring flights around the volcano[198] as well as large numbers of helicopter tour companies operating and landing in the vicinity, as well as small private aviation and sightseeing fixed wing aircraft circling the eruption site. Many unmanned drones are also active around the volcano site.[199]

Roads and utilities

The main concerns are if lava flows were to reach the main highway to Keflavik and the airport, Road 41,[200] as well as the south coast road, Road 427, an important evacuation route for the town of Grindavík.[201]

In addition, if the lava flows travel northwards, an important high-voltage transmission line to Keflavik is in danger of being cut off. Communications fiber routes both to the north and south side of the volcano are also in danger of being cut off, which could impact communications and the data center industry in Keflavik. However, the fissure's location as of August 2022 is unlikey to affect the roads and utilities.

Within a week of the start of the 2021 eruption, power and fiber-optic lines were laid from Grindavík to support operations of the authorities near the eruption site as well as 4G cell and TETRA masts were set up to ensure access to communications and emergency services (112) for tourists and authorities.[202]

Lava flow experiments

In July 2021, in collaboration with Iceland's Department of Civil Protection and Emergency Management, utility companies conducted an experiment by burying various types of utilities (underground electrical cables, fibers, water lines and sewage line) with varying levels of insulation in order to see how overland lava flows affect buried utilities.[203][204] Another separate experiment was conducted by constructing large levees to control direction of lava flows; they were moderately effective in controlling slow moving lava flows.[205]

In July 2023, during the Litli Hrútur eruption, Icelandic electrical grid operator Landsnet constructed a dummy electricity pole, as well installing a high voltage underground electrical cable in the path of lava as an experiment to study the lava flow's potential effects on the electricity network.[206]

Tourism management

The Fagradalsfjall volcano site is unusual in terms of its close proximity to Iceland's main international airport and popular tourist sites such as the Blue Lagoon. The site is only around 60 km (37 mi) from Reykjavík. Access is a short distance from Grindavík along paved Road 427, with limited parking available by the trailhead. Depending on the route taken, the hike to the new site is around 6–8 km (3.7–5.0 mi) each way, taking around 3–6 hours in hiking time (not including sightseeing or stops). Many parts of the route are extremely steep with uneven rocky ground, as well as being poorly signed due to the recency of the eruption. Depending on the wind direction, toxic gas pollution can be a risk as well as unpredictable lava flows and new fissures opening up.

Due to its easy access, a very large number of locals and tourists have visited the site. Around 10,000 people visited the 2022 eruption on its first day.[207] Authorities have kept the site open for the most part, and try to inform rather than ban people from visiting the site.[208] There have been no deaths reported as a result of the eruption, However, many injuries have been indirectly caused by the volcano, due to inadequately equipped tourists visiting the site with reports of broken ankles,[209] lost travellers and hypothermia as weather is very unpredictable in the area.

Authorities have used Location Based SMS messages to inform and warn tourists travelling to the site to be prepared. The site is manned during busy periods by the volunteers from the Icelandic Association for Search and Rescue, as well as local police.[210] The site has had to be evacuated at least once due to fast moving lava flows.[211] The site was closed for 2 days from 7 August 2022 due to inclement weather, however groups of tourists who did not heed the closures had to be rescued by the local volunteer search and rescue team, Þorbjörn.[195]

During the 2023 Litli Hrútur eruption, new challenges were faced in managing the tourism flow with more closures in place than previous eruptions. The 2023 eruption produced more volcanic gases as well as sparking some of Iceland's largest moss wildfires, creating much more dangerous respiratory risks for hikers. The 2023 eruption is also further away from main roads, making the hike more difficult (over 4-5 hours) and access for emergency services more challenging.[212]

Supposed burial site

The area where the volcano first erupted is thought to be the burial site of an early Norse settler Ísólfur frá Ísólfsstöðum [ˈiːsˌoulvʏr frauː ˈiːsˌoul(f)sˌstœːðʏm].[213] However, a quick archaeological survey of Geldingadalur after the eruption started in 2021 found no evidence of human remains in the area.[214]

1943 accident

On 3 May 1943, LTG Frank Maxwell Andrews, a U.S. Army senior officer, founder of the United States Army Air Forces, and a leading candidate for command of the Allied invasion of Europe was killed along with 14 others when their B-24 aircraft Hot Stuff crashed into the side of the mountain.[215][216]

See also

Notes

References

- "Kortasjá". kortasja.lmi.is. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- Pedersen, G. B. M. (February 2016). "G.M. Pedersen, Semi-automatic classification of glaciovolcanic landforms: An object-based mapping approach based on geomorphometry". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 311: 29–40. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2015.12.015.

- "Fagradalsfjall: Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- "Volcanic eruption has started near Litli-Hrútur". Iceland Monitor. 10 July 2023.

- "Fagradalsfjall". Volcano Discovery. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- "Global Volcanism Program | Krýsuvík-Trölladyngja". Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ""Small" volcanic eruption in Iceland lights up night sky near Reykjavik". France 24. 20 March 2021. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Sæmundsson, Kristján; Sigurgeirsson, Magnús Á. (25 June 2018). "Hvað getið þið sagt mér um eldstöðvakerfið sem kennt er við Fagradalsfjall?". Vísindavefurinn. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- "Upptök gossins eru í Geldingadal". www.mbl.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- "Iceland volcano: Eruption under way in Fagradalsfjall, near Reykjavik". The Guardian. 20 March 2021. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- "The Civil protection crisis level lowered from orange to yellow for the Volcano in Fagrdalsfjall | News". Icelandic Meteorological Office. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- Einarsson, Guðni (14 July 2021). "Óljóst hvað stýrir gosóróa". mbl.is. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- Ravilious, Kate (7 July 2021). "Terrawatch: witnessing a 'lava shield' volcano form". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- Churm, Philip Andrew (10 May 2021). "An erupting volcano in Iceland is drawing tourists from around the world". EuroNews. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- Sherwood, Harriet (18 April 2021). "Lava in a cold climate: Icelanders rush to get wed at volcano site". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- "Volcano near Iceland's main airport erupts again after series of earthquakes". CBS News. Archived from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- "Eruption Information".

- Gunnarsson, Oddur Ævar (10 July 2023). "Vísir í beinni í þyrluflugi yfir gosstöðvum". Vísir.

- "„Þetta er búið í bili"". mbl.is. 6 August 2023.

- Halldórsson, Skúli (5 May 2021). "Hraunið mun heita Fagradalshraun". mbl.is. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- "Krýsuvík-Trölladyngja". Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- "Krýsuvík-Trölladyngja". Smithsonian Institution: Global Volcanism Program.

- See eg.: Geirsson, H., Parks, M., Vogfjörd, K., Einarsson, P., Sigmundsson, F., Jónsdóttir, K., Drouin, V., Ófeigsson, B. G., Hreinsdóttir, S., and Ducrocq, C.: The 2020 volcano-tectonic unrest at Reykjanes Peninsula, Iceland: stress triggering and reactivation of several volcanic systems, EGU General Assembly 2021, online, 19–30 Apr 2021, EGU21-7534, https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu21-7534 Archived 20 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 2021. https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EGU21/EGU21-7534.html Archived 21 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 6 April 2021

- Keiding, M.; Árnadóttir, T.; Sturkell, E.; Geirsson, H.; Lund, B. (2008). "Strain accumulation along an oblique plate boundary: the Reykjanes Peninsula, southwest Iceland". Geophysical Journal International. 172 (2): 861–872. Bibcode:2008GeoJI.172..861K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2007.03655.x.

- "Íslensk eldfjallavefsjá". icelandicvolcanos.is. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- "Fagradalsfjall volcano in Iceland erupts for the first time in 6,000 years". iNews. 20 March 2021. Archived from the original on 1 September 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- See eg.: Geirsson, H., Parks, M., Vogfjörd, K., Einarsson, P., Sigmundsson, F., Jónsdóttir, K., Drouin, V., Ófeigsson, B. G., Hreinsdóttir, S., and Ducrocq, C.: The 2020 volcano-tectonic unrest at Reykjanes Peninsula, Iceland: stress triggering and reactivation of several volcanic systems, EGU General Assembly 2021, online, 19–30 Apr 2021, EGU21-7534, https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu21-7534 Archived 20 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 2021. https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EGU21/EGU21-7534.html Archived 21 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 6 April 2021

- "Hvorki hægt að sjá fyrir goslok né áframhald". RÚV. 12 September 2021. Archived from the original on 14 September 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- Sæberg, Árni; Pétursson, Heimir Már (19 August 2021). "Fimm mánuðir frá upphafi eldgossins í Fagradalsfjalli". Vísir. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- "Eldgos í Fagradalsfjalli". University of Iceland Institute of Earth Sciences. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- Andrews, Robin George (4 August 2022). "Iceland eruption may be the start of decades of volcanic activity". National Geographic.

- Peltier, Elian (4 March 2021). "In Iceland, 18,000 earthquakes over days signal possible eruption on the horizon". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- "M 5.6 - 11 km SW of Álftanes, Iceland". USGS-ANSS. USGS. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- "M 5.6 - 6 km SE of Vogar, Iceland". USGS-ANSS. USGS. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Hafstað, Vala (18 March 2021). "Earthquakes on Reykjanes peninsula explained". Iceland Monitor. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Frímann, Jón (24 February 2021). "Earthquake with magnitude 5,7 in Reykjanes volcano (update at 12:28 UTC)". Iceland Geology. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- "Volcano erupts near Iceland's capital Reykjavik". BBC. BBC. 20 March 2021. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Jónsson, Loftur. "Hraun" (PDF). Örnefnastofnun. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- "Aukagígur sækir í sig veðrið". www.mbl.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- Bindeman, I. N.; Deegan, F. M.; Troll, V. R.; Thordarson, T.; Höskuldsson, Á; Moreland, W. M.; Zorn, E. U.; Shevchenko, A. V.; Walter, T. R. (29 June 2022). "Diverse mantle components with invariant oxygen isotopes in the 2021 Fagradalsfjall eruption, Iceland". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 3737. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.3737B. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31348-7. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 9243117. PMID 35768436.

- "Long dormant volcano comes to life in southwestern Iceland". US News. Associated Press. 19 March 2021. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Hafstað, Vala (20 March 2021). "'Best possible location' for eruption". Iceland Monitor. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Fontaine, Andie Sophia (19 March 2021). "Eruption at Fagradalsfjall". Grapevine. Reykjavik, IS. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Elliott, Alexander (19 March 2021). "Volcanic eruption: What we know so far". RÚV. Iceland. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- We visited the volcano in Iceland & it blew our mind (video). RVK. Newscast #86. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021 – via Youtube.

- "Vísbendingar um dyngjugos sem getur varað í ár". www.mbl.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- "Gosið sést vel af höfuðborgarsvæðinu". www.mbl.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ""Þetta er hálfgerð Þjóðhátíð hérna"". www.mbl.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ""Ekkert í líkingu við það sem við höfum séð áður"". www.mbl.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- Björnsson, Ingvar Þór (13 April 2021). "Telja fjóra nýja gíga hafa opnast". RÚV (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- "BREAKING: New Fissure Opens North Of Geldingadalur, Area Evacuated". The Reykjavik Grapevine. 5 April 2021. Archived from the original on 5 April 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- Pétursson, Vésteinn Örn; Hall, Sylvia (5 April 2021). "Ný sprunga að opnast á Reykjanesskaga" [A new crack opens on the Reykjanes peninsula]. Vísir (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 5 April 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- "Ný gossprunga skammt frá gosstöðvum í Geldingadölum" [New eruption fissure close to eruption sites in Geldingadalur]. Veðurstofa Íslands (in Icelandic). 5 April 2021. Archived from the original on 5 April 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- https://www.ruv.is/frett/2021/04/05/tvaer-nyjar-sprungur-og-hraunid-rennur-i-meradali Archived 21 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine Tvær nýjar sprungur og hraunið rennur í Meradali. Ruv.is. 5 April 2021 - 14:05. Retrieved 6 April 2021

- https://www.ruv.is/frett/2021/04/05/gosid-hefur-vaxid-10-rummetrar-af-kviku-a-sekundu Archived 5 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine Gosið hefur vaxið - 10 rúmmetrar af kviku á sekúndu. Ruv.is Retrieved: 6 April 2021

- See also: http://jardvis.hi.is/eldgos_i_geldingadolum Archived 7 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine Eldgos í geldingadölum. Háskóli Íslands. Jarðvínsindastofnun. Retrieved: 6 April 2021

- "Reykjanes surprise". VolcanoCafe. 5 April 2021. Archived from the original on 5 April 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- https://en.vedur.is/#tab=quakes Archived 6 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine Specialist remark. Earthquake page of Icelandic Met Office. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- See also https://www.ruv.is/frett/2021/04/07/ny-sprunga-buin-ad-opnast Archived 7 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine RÚV: Ný sprunga búin að opnast. Retrieved 7 April 2021

- "From Iceland — A New Fissure Has Opened At Geldingadalur". The Reykjavik Grapevine. 7 April 2021. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Ćirić, Jelena (7 April 2021). "Reykjanes Eruption: Third Fissure Opens". Iceland Review. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- See eg. https://www.ruv.is/frett/2021/04/10/ny-sprunga-opnadist-i-geldingadolum-i-nott Archived 13 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine RÚV. Ný sprunga opnaðist í Geldingadölum í nótt. Retrieved: 13 April 2021

- "Global Volcanism Program | Report on Krysuvik-Trolladyngja (Iceland) — May 2021". volcano.si.edu. doi:10.5479/si.gvp.bgvn202105-371030. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- Julavits, Heidi (16 August 2021). "Chasing the Lava Flow in Iceland". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- "Skjálfti upp á 3,2 við Kleifarvatn -- gosvirkni svipuð". RÚV (in Icelandic). 3 May 2021. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- "Fagradalsfjall volcano update: Lava overflows dam, enters valley towards southern Ring Road now in dager being cut". 23 May 2021. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- "Gosið í fullu fjöri". mbl.is. 1 July 2021. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- Tryggvason, Tryggvi Páll (16 August 2021). "Nýjasta gosopið í góðum gír". Vísir. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- Arnardóttir, Lovísa (20 August 2021). "Nýjar sprungur á Gónhóli". Fréttabladid. Archived from the original on 7 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- Jónsdóttir, Hallgerður Kolbrún E. (11 September 2021). "Kvika flæðir undan gömlu hrauni í Geldingadölum". Vísir. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- "Eldgosið staðið yfir í fimm mánuði". mbl.is. 19 August 2021. Archived from the original on 1 September 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- "Fagradalsfjall 10. ágúst 2021". University of Iceland Institute of Earth Sciences. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- http://jardvis.hi.is/eldgos_i_fagradalsfjalli Archived 12 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine Jarðvísíndastofnun Háskóla Íslands Retrieved: 13 April 2021

- "New trace element and isotope analyses of the Geldingadalir lava". Institute of Earth Sciences. 1 April 2021. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- "Characterisation of rock samples collected in the first week of the eruption-trace elements and Pb-isotopes" (PDF). Institute of Earth Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- "Characterisation of rock samples collected on the 1st and 2nd days of the eruption in Geldingdalur". Institute of Earth Sciences. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- Eldgos í Fagradalsfjalli. Archived 12 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine Jarðvísindastofnun. Háskóli Íslands. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- Ioana-Bogdana Radu, Henrik Skogby, Valentin R. Troll, Frances M. Deegan, Harri Geiger, Daniel Müller & Thor Thordarson: Water in clinopyroxene from the 2021 Geldingadalir eruption of the Fagradalsfjall Fires, SW-Iceland. In: Bull Volcanol 85, 31 (2023). DOI:10.1007/s00445-023-01641-4

- Eldgosið síðasta sólarhringinn – aukin sprengivirkni. Archived 28 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine RúV. 27 April 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021

- "Eldskýstrßokar við eldstöðvarnar í gær". RÚV. 29 April 2021. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- "Icelandic volcano becomes more volatile and powerful". Euronews. 3 May 2021. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- Bressen, David (10 May 2021). "Volcanic Eruption Illuminates Reykjavik's Night Sky With Lava Fountains Up to 460 Meters High". Forbes. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- "Myndarlegir strókar standa upp af gosinu". RÚV. 5 May 2021. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- "Gígurinn þeytir kviku 300 metra upp í loft". RÚV. 2 May 2021. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- Steinþórsson, Sigurður (24 June 2021). "Hvaðan kemur vatnið sem veldur sprengingum í gígnum í Geldingadölum?". Vísindavefurinn. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- Hallsdóttir, Esther (24 June 2021). "Eldgamalt vatn veldur sprengingunum". mbl.is. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- "Eldgosið tveggja mánaða og tvöfalt stærra en í upphafi". RUV.is. 19 May 2021. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- Guðrún Hálfdánardóttir (4 June 2021). "Breytingar á óróavirkni gossins". mbl.is. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- https://www.ruv.is/frett/2021/05/11/different-eruption-than-we-are-used-to Archived 12 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine "Different eruption than we are used to" RúV (English language pages). 11 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021

- Hafstað, Vala (23 March 2021). "Long-Lasting Shield Volcano Eruption? Magma from Mantle". Iceland Monitor. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- https://www.ruv.is/frett/2021/05/11/stor-kutur-fullur-af-kviku-undir-gosinu Archived 13 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine Stór kútur fullur af kviku undir gosinu. RÚV. 11 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021. See also the [data from University of Iceland (data from 10 May 2021, retrieved 13 May 2021]) http://jardvis.hi.is/eldgos_i_fagradalsfjalli}}%5B%5D

- Ásgrímsson, Þorsteinn (15 May 2021). "Leggja lokahönd á fyrri varnargarðinn". mbl.is. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- Lilja Hrund Ava Lúðvíksdóttir (22 May 2021). "Komi ekki á óvart að hraun renni yfir varnargarðinn". mbl.is. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- Rúnarsson, Bjarni (22 May 2021). "Logandi hraunflaumurinn rennur niður í Nátthaga". RUV.is. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- RÚV (25 May 2021). "Lava tops barriers as small earthquake draws attention". Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- Ólafsdóttir, Kristín (5 June 2021). "Hraunspýja rauf vestari varnargarðinn". Vísir. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- Sigurðardóttir, Elísabet Inga (4 June 2021). "Hraun komið yfir gönguleiðina upp á útsýnishólinn". Vísir. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- "Hætta á að hraun flæði yfir á fleiri stöðum". RÚV. 13 June 2021. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- "Reyna að stýra leið hraunflæðis". mbl.is. 16 June 2021. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- Sæberg, Árni (25 June 2021). "Varnargarður rís í Nátthaga". Vísir. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- "Hraunið nái að Suðurstrandarvegi á næstu vikum". mbl.is. 25 June 2021. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- "Almannavarnir munu ekki leggja hraunbrú". mbl.is. 1 July 2021. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- Elliott, Alexander (15 June 2021). "Nine football pitches of lava per day". RÚV. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- "Mun stærra en í upphafi". mbl.is. 18 June 2021. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- "Hraunið orðið hundrað metrar að þykkt". RÚV. 9 June 2021. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- "Allar mælingar benda til að hraunflæðið sé svipað". RÚV. 10 June 2021. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- "Strókavirkni jókst í eldgosinu í nótt". RÚV. 11 June 2021. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- Einarsson, Guðni (6 July 2021). "Gígurinn fylgir ekki flæðinu". mbl.is. Archived from the original on 7 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- Amos, Jonathan (7 July 2021). "Iceland's spectacular volcano tracked from space". BBC. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- Grettisson, Valur (8 July 2021). "RVK Newscast #115: The Odd Rhythm Of The Volcano & A Helicopter Dispute". Reykjavík Grapevine. Archived from the original on 10 July 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- Unnarsson, Kristján Már (6 July 2021). "Gosið í dvala í sólarhring í lengsta hléi frá upphafi". Vísir. Archived from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- "Did Part of Crater Rim Collapse?". Iceland Monitor. 30 June 2021. Archived from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- Kiner, Brittnee (1 July 2021). "Volcano Revives Itself After Fears Of Eruption Ending". Reykjavík Grapevine. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- "Ljóst að gosinu er ekki lokið". mbl.is. 29 June 2021. Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- "Lítil sem engin virkni í eldgosinu". mbl.is. 1 July 2021. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- Pétursson, Vésteinn Örn (4 July 2021). ""Gerum allt eins ráð fyrir því að óróinn taki sig upp að nýju"". Vísir. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- Unnarsson, Kristján Már (4 July 2021). "Hraunslettur í gígnum á ný eftir sextán stunda goshlé". Vísir. Archived from the original on 4 July 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- "Ennþá virkni í gosinu". mbl.is. 9 July 2021. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- Unnarsson, Kristján Már (10 July 2021). "Hraunslettur í gígnum á ný og óróinn rýkur upp". Vísir. Archived from the original on 10 July 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- Ólafsdóttir, Kristín (11 July 2021). "Hraunið streymir niður í Meradali gegnum gat í gígnum". Vísir. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Þórhallsson, Markús Þ. (13 July 2021). "Hraunstraumur rennur fagurlega niður í Meradali". RÚV. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- "Öflugur hraunfoss rennur úr gígnum niður í Meradali". RÚV. 10 July 2021.

- Kolbeins, Steinar Ingi (16 July 2021). "Hraun rennur taktfast niður í Meradali". mbl.is. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- "Mikið gengið á við gosstöðvarnar". mbl.is. 15 July 2021. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- "Dregur úr kvikumagninu segir Magnús Tumi - enginn órói". RÚV. 16 July 2021. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- "Gosóróinn farinn upp og gígurinn að fyllast". mbl.is. 16 July 2021. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- Ríkharðsdóttir, Karítas (17 July 2021). "Gosóróinn dottinn niður á ný". mbl.is. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- "Hraunið rennur meira í austurátt og niður í Meradali". RÚV. 27 July 2021. Archived from the original on 1 September 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- Tryggvason, Tryggvi Páll (27 August 2021). "Gosið hafi mannast". Vísir. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- Unnarsson, Kristján Már (8 July 2021). "Eldgosið í Fagradalsfjalli orðið stærra en meðalgos á svæðinu". Vísir. Archived from the original on 10 July 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- Bjarnar, Jakob (29 July 2021). "Gosið hrekkjótt og lætur vísindamenn hafa fyrir sér". Vísir. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- "Fagradalsfjall 10 August 2021". University of Iceland Institute of Earth Sciences. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- Kolbeinsson Proppé, Óttar (21 August 2021). "Hraun rennur aftur í Nátthaga en langt í Suðurstrandarveg". Vísir. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- "Augnakonfekt í Nátthaga". RÚV. 27 August 2021. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- Jónasson, Magnús H. (21 August 2021). "Nýjar sprungur á Gónhóli". Fréttablaðið. Archived from the original on 7 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- "Lengsta goshlé frá upphafi". mbl.is. 10 September 2021. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- "Kvikan brýtur sér leið upp á yfirborðið". mbl.is. 11 September 2021. Archived from the original on 12 September 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- "Gosrásin upp í gíginn hafði stíflast". mbl.is. 12 September 2021. Archived from the original on 12 September 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- "Gígbarmurinn rís hæst í 334 metra hæð". mbl.is. 14 September 2021. Archived from the original on 14 September 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- "Púlsavirkni í gígnum í fyrsta sinn síðan í apríl". mbl.is. 12 September 2021. Archived from the original on 13 September 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- Ómarsdóttir, Alma (14 September 2021). "Hraðari púlsavirkni: Gýs átta sinnum á klukkustund". RÚV. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- Tryggvason, Tryggvi Páll; Pétursdóttir, Lillý Valgerður (15 September 2021). "Varð vitni að því þegar allt fór af stað: "Byrjar að flæða alveg ótrúlegt magn"". Vísir. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- Pétursdóttir, Lillý Valgerður; Ólason, Samúel Karl (16 September 2021). "Orðið lengsta gos aldarinnar: "Það má bara búast við öllu"". Vísir. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- "Hraunið nær nú yfir 4,8 ferkílómetra". mbl.is. 20 September 2021. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- "Óróinn minnkar óvenjulega hægt". mbl.is. 19 September 2021. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- "The Civil protection crisis level lowered from alert to uncertainty phase | News". Icelandic Meteorological office. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- "Global Volcanism Program | Report on Fagradalsfjall (Iceland) — September 2022". volcano.si.edu. doi:10.5479/si.gvp.bgvn202209-371032. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- "Global Volcanism Program | Report on Fagradalsfjall (Iceland) — September 2022". volcano.si.edu. doi:10.5479/si.gvp.bgvn202209-371032. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- "Pictured: Spectators flock to dramatic volcanic eruption in Iceland". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 5 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- "Volcano near Iceland's main airport erupts after eight month pause". NBC. Archived from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- "Volcano near Iceland's capital, main airport erupts again after 8-month pause". CBC. Archived from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- "Global Volcanism Program | Report on Fagradalsfjall (Iceland) — September 2022". volcano.si.edu. doi:10.5479/si.gvp.bgvn202209-371032. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- "Volcano erupts in Iceland after dozens of earthquakes near Reykjavík". New York Post. Archived from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- "Volcano Near Iceland's Main Airport Erupts Again". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- "Volcano erupts near Iceland's capital in seismic hot spot". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- "Deja Vu As Volcano Erupts Again Near Iceland Capital". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- "New eruption is estimated bigger than previous one". Archived from the original on 2 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- "Global Volcanism Program | Report on Fagradalsfjall (Iceland) — September 2022". volcano.si.edu. doi:10.5479/si.gvp.bgvn202209-371032. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- "Global Volcanism Program | Report on Fagradalsfjall (Iceland) — September 2022". volcano.si.edu. doi:10.5479/si.gvp.bgvn202209-371032. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- The Reykjavík Grapevine Newscast 208: Lava Flow Reducing And Big Drugs Bust

- Krmíček, Lukáš; Troll, Valentin R.; Galiová, Michaela Vašinová; Thordarson, Thor; Brabec, Marek (2022). "Trace element composition in olivine from the 2022 Meradalir eruption of the Fagradalsfjall Fires, SW-Iceland (Short Communication)". Czech Polar Reports. 12 (2): 222–231. doi:10.5817/CPR2022-2-16. ISSN 1805-0697. S2CID 257129830.

- Bjarkason, Jóhannes (10 July 2023). "Large Earthquake Rocks Iceland As Scientists Expect Eruption". The Reykjavík Grapevine.

- "Iceland volcano: Lava bursts through ground after intense earthquakes". BBC. 11 July 2023.

- "Iceland volcano eruption prompts warnings to stay away from Litli-Hrútur mountain". ABC News. 11 July 2023.

- Ólason, Samúel Karl (11 July 2023). "Verulega minni kraftur en í gær". Vísir.

- Jósefsdóttir, Sólrún Dögg (10 July 2023). "Segir gosið miklu öflugra en síðustu tvö". Vísir.

- Valsson, Andri Yrkill (10 July 2023). "Tilkomumikið en stórhættulegt sjónarspil". RÚV.

- Zubenko, Iryna (11 July 2023). "New Eruption: Bigger Than Previous Two, Less Powerful Today". The Reykjavík Grapevine.

- Jósefsdóttir, Sólrún Dögg (10 July 2023). "Segir gosið miklu öflugra en síðustu tvö". Vísir.

- Frímann, Jón (11 July 2023). "Update on the eruption at Litli-Hrútur on 11th July 2023 at 17:18 UTC". Iceland Geology.

- Sumarliðadóttir, Karlotta Líf (11 July 2023). "Gossprungan þrefalt lengri en í fyrra". mbl.is.

- Egilsdóttir, Urður (12 July 2023). "Ekki komið nafn á hraunið". mbl.is.

- Gunnarsson, Oddur Ævar. "Svipað hraunrennsli nú og þegar fyrsta gosið náði hámarki". Vísir.

- "Gígurinn hækkar um þrjá metra á dag". mbl.is. 16 July 2023.

- "Rennur í átt að hrauninu í Merardölum". mbl.is. 14 July 2023.

- Jósefsdóttir, Sólrún Dögg (15 July 2023). "Birtir myndir af hrauninu flæða yfir það gamla". Vísir.

- Unnarsson, Kristján Már; Árnason, Eiður Þór. "Hálft Reykjanesið geti farið undir eld". Vísir.

- "Unique Video of a Volcano Crater Collapse in Iceland at Litli Hrútur". SIGGIZOO. 26 July 2023 – via YouTube.

- Hannesdóttir Diego, Hugrún (19 July 2023). "Gígbarmurinn brast og hraun rennur í nýjan farveg". RÚV.

- "Hraunið flæði aftur til suðurs" [The lava flows back to the south]. mbl.is (in Icelandic). 20 July 2023.

- Sigurðsson, Bjarki (23 July 2023). "Veggir gígsins muni hrynja innan skamms". Vísir.

- Adam, Darren (24 July 2023). "Crater rim collapse on north side". RÚV.

- "olcanic eruption at Litla-Hrút, results of measurements on July 23". Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Iceland. 24 July 2023.

- Gunnarsson, Oddur Ævar (23 July 2023). "Hraunrennslið nú alfarið neðanjarðar". Vísir.

- Gunnarsson, Oddur Ævar (14 July 2023). "Svipað hraunrennsli nú og þegar fyrsta gosið náði hámarki". Vísir.

- {{cite news |url=https://www.volcanodiscovery.com/de/iceland/reykjanes/volcano-seismic-crisis-july2023/updates.html

- Árnason, Eiður Þór (2 August 2023). "Hraunflæði minnkar og vísbending um að goslok nálgist". Vísir.

- "Dregur úr gosinu líkt og verið sé að tæma blöðru". mbl.is. 2 August 2023.

- "Many people walk to the eruption sites". Iceland Monitor. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- Vogar, Sveitarfélagið. "Náttúruvá". Vogar (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 5 August 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- Almannavarnadeild Ríkislögreglustjóra (1 January 2021). "Viðbragðsáætlun vegna eldgoss við Grindavík" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- Almannavarnadeild Ríkislögreglustjóra (6 December 2019). "Rýmingaráætlun fyrir höfuðborgarsvæðið". Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Öryggi fólks á svæðinu aðalatriðið". www.mbl.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 5 August 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Gönguleiðin ekki fyrir óvana". www.mbl.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- rebekkali (8 August 2022). "Björgunarsveitir leita af sér allan grun við gosstöðvar". RÚV (in Icelandic). Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- holmfridurdf (29 May 2022). "Undirbúa eldgosavarnir við Grindavík og Svartsengi". RÚV (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- urduro (3 August 2022). "Engin röskun á flugi". RÚV (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- sigridurhb; peturm (3 August 2022). "Gosið séð úr þyrlu Landhelgisgæslunnar". RÚV (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Gætu sett bann við drónaflugi við eldgosið". www.mbl.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- Olgeirsson, Vésteinn Örn Pétursson,Birgir. "Hætta á að hraunstraumar gætu lokað Reykjanesbraut - Vísir". visir.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - kristins (19 June 2021). "Hraun gæti flætt á Suðurstrandarveg innan 2ja vikna". RÚV (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Bætt fjarskiptasamband við Gosstöðvarnar". Míla ehf (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 4 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Þola jarðstrengir álag frá hraunflæðinu? | Fréttir". EFLA.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Ljósleiðari undir hrauni - niðurstöður prófunar". Míla ehf (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 10 March 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Varnargarðurinn ofan við Nátthaga". Almannavarnir (in Icelandic). 21 May 2021. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Mæla hvort að rafstrengir og línur þoli hraun". www.mbl.is (in Icelandic). Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- bjarnipetur (3 August 2022). "Talið að um tíu þúsund séu við gosstöðvarnar". RÚV (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Erfiðara fyrir "hinn almenna túrista"". www.mbl.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Maður ökklabrotnaði við gosstöðvarnar". www.mbl.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- astahm (4 August 2022). "Hætta á lífshættulegum slysum við gosstöðvarnar". RÚV (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- andriyv (15 September 2021). "Rýming við gosstöðvar vegna aukins hraunflæðis". RÚV (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Hunsuðu fyrirmæli og gengu upp að gígnum". www.mbl.is (in Icelandic). Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- "Reykjanes eruption in Iceland continues at steady pace, might go on for weeks". Volcano Discovery. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- Másson, Snorri (21 March 2021). "Mannvistarleifar glötuðust ekki". mbl.is. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- "Mt Fagradalsfjall". Visit Reykjanes. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Yenne, Bill (2015). Hit the Target: Eight men who led the Eighth Air Force to victory over the Luftwaffe. Penguin Group. p. 184. ISBN 9780698155015. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021 – via Google Books.

External links

- "Fagradalsfjall". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- Data from University of Iceland re. the eruption at Fagradalsfjall (continuously updated)

- Icelandic Met Office: Gas dispersion forecast

- A volcanic eruption has begun — Icelandic Met Office

- Video by Icelandic Meteorological Office taken a few hours after the eruption started

- Live video of the March 2021 eruption

- RÚV. Video of the eruption on 12 April 2021

- Interactive 3D model of the lava flows as of 18 April 2021.