Little Moreton Hall

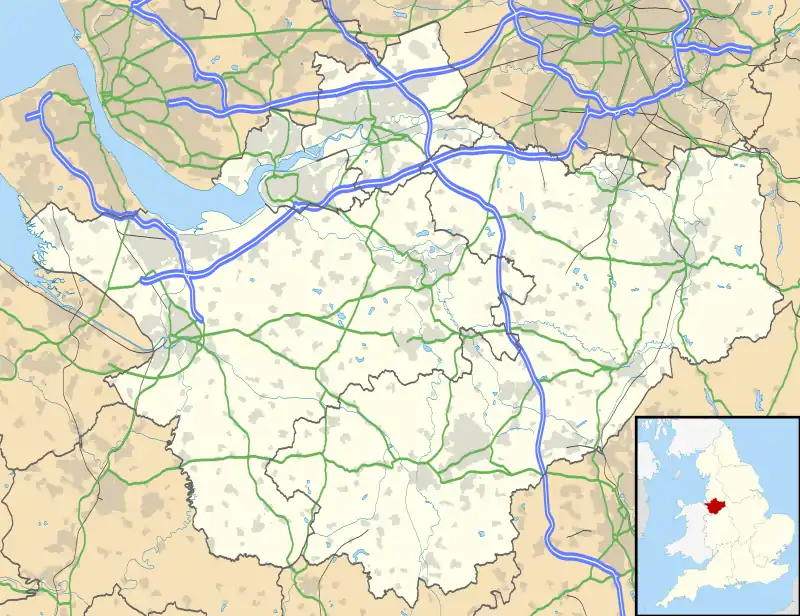

Little Moreton Hall, also known as Old Moreton Hall,[lower-alpha 1] is a moated half-timbered manor house 4.5 miles (7.2 km) southwest of Congleton in Cheshire, England.[2] The earliest parts of the house were built for the prosperous Cheshire landowner William Moreton in about 1504–08, and the remainder was constructed in stages by successive generations of the family until about 1610. The building is highly irregular, with three asymmetrical ranges forming a small, rectangular cobbled courtyard. A National Trust guidebook describes Little Moreton Hall as being "lifted straight from a fairy story, a gingerbread house".[3] The house's top-heavy appearance, "like a stranded Noah's Ark", is due to the Long Gallery that runs the length of the south range's upper floor.[4]

| Little Moreton Hall | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Little Moreton Hall's south range, constructed in the mid-16th century. The weight of the third-storey glazed gallery, possibly added at a late stage of construction, has caused the lower floors to bow and warp.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The house remained in the possession of the Moreton family for almost 450 years, until ownership was transferred to the National Trust in 1938. Little Moreton Hall and its sandstone bridge across the moat are recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade I listed building,[5][6] and the ground on which Little Moreton Hall stands is protected as a Scheduled Monument.[6][lower-alpha 2] The house has been fully restored and is open to the public from April to December each year.

At its greatest extent, in the mid-16th century, the Little Moreton Hall estate occupied an area of 1,360 acres (550 ha) and contained a cornmill, orchards, gardens, and an iron bloomery with water-powered hammers. The gardens lay abandoned until their 20th-century re-creation. As there were no surviving records of the layout of the original knot garden, it was replanted according to a pattern published in the 17th century.

History

The name Moreton probably derives from the Old English mor meaning "marshland" and ton, meaning "town". The area where Little Moreton Hall stands today was named Little Moreton to distinguish it from the nearby township of Moreton cum Alcumlow, or Greater Moreton. The Moreton family's roots in Little Moreton can be traced to the marriage in 1216 of Lettice de Moreton to Sir Gralam de Lostock, who inherited land there; succeeding generations of the de Lostocks adopted the name of de Moreton.[7] Gralam de Lostock's grandson, Gralam de Moreton, acquired valuable land from his marriages to Alice de Lymme and then Margery de Kingsley. Another grandson, John de Moreton, married heiress Margaret de Macclesfield in 1329, adding further to the estate.[8] The family also purchased land cheaply after the Black Death epidemic of 1348.[9] Four generations after John de Moreton, the family owned sixteen messuages, a mill and 700 acres (280 ha) of land, comprising 560 acres of ploughland, 80 acres of pasture, 20 acres of meadow, 20 acres of wood and 20 acres of moss.[10] The Dissolution of the Monasteries in the mid-16th century provided further opportunities for the Moretons to add to their estate,[9] and by the early years of Elizabeth I's reign, William Moreton II owned two water mills and 1,360 acres (550 ha) of land valued at £24 7s 4d, including 500 acres of ploughland, 500 acres of pasture and 100 acres of turbary.[11]

Little Moreton Hall first appears in the historical record in 1271, but the present building dates from the early 16th century.[6][lower-alpha 3] The north range is the earliest part of the house. Built between 1504 and 1508 for William Moreton (died 1526), it comprises the Great Hall and the northern part of the east wing.[13] A service wing to the west, built at the same time but subsequently replaced, gave the early house an H-shaped floor plan.[12] The east range was extended to the south in about 1508 to provide additional living quarters, as well as housing the Chapel and the Withdrawing Room.[13] In 1546 William Moreton's son, also called William (c. 1510–63), replaced the original west wing with a new range housing service rooms on the ground floor as well as a porch, gallery, and three interconnected rooms on the first floor, one of which had access to a garderobe.[7] In 1559 William had a new floor inserted at gallery level in the Great Hall,[lower-alpha 4] and added the two large bay windows looking onto the courtyard, built so close to each other that their roofs abut one another.[14][15] The south wing was added in about 1560–62 by William Moreton II's son John (1541–98).[16] It includes the Gatehouse and a third storey containing a 68-foot (21 m) Long Gallery,[17] which appears to have been an afterthought added on after construction work had begun.[18] A small kitchen and Brew-house block was added to the south wing in about 1610, the last major extension to the house.[19]

The fortunes of the Moreton family declined during the English Civil War. As supporters of the Royalist cause, they found themselves isolated in a community of Parliamentarians.[20] Little Moreton Hall was requisitioned by the Parliamentarians in 1643 and used to billet Parliamentary soldiers. The family successfully petitioned for its restitution,[21] and survived the Civil War with their ownership of Little Moreton Hall intact, but financially they were crippled.[20] They tried to sell the entire estate, but could only dispose of several parcels of land. William Moreton died in 1654 leaving debts of £3,000–£4,000 (equivalent to about £12–16 million as of 2010[22][lower-alpha 5]), which forced his heirs to remortgage what remained of the estate.[23] The family's fortunes never fully recovered, and by the late 1670s they no longer lived in Little Moreton Hall, renting it out instead to a series of tenant farmers. The Dale family took over the tenancy in 1841, and were still in residence more than 100 years later.[1] By 1847 most of the house was unoccupied, and the deconsecrated Chapel was being used as a coal cellar and storeroom.[24] Little Moreton Hall was in a ruinous condition; its windows were boarded up and its roof was rotten.[25]

During the 19th century, Little Moreton Hall became "an object of romantic interest" among artists;[24] Amelia Edwards used the house as a setting for her 1880 novel Lord Brackenbury.[26] Elizabeth Moreton, an Anglican nun,[lower-alpha 6] inherited the almost derelict house following the death of her sister Annabella in 1892. She restored and refurnished the Chapel, and may have been responsible for the insertion of steel rods to stabilise the structure of the Long Gallery. In 1912 she bequeathed the house to a cousin, Charles Abraham, Bishop of Derby, stipulating that it must never be sold.[27][lower-alpha 7] Abraham opened up Little Moreton Hall to visitors, charging an entrance fee of 6d (equivalent to about £8 in 2010[22][lower-alpha 8]) collected by the Dales, who conducted guided tours of the house in return.[1]

Abraham carried on the preservation effort begun by Elizabeth Moreton until he and his son transferred ownership to the National Trust in 1938.[28] The Dale family continued to farm the estate until 1945, and acted as caretakers for the National Trust until 1955.[1] The Trust has carried out extensive repair and restoration work, including re-roofing; restoration of elements of the hall's original appearance, and removal of some painted patterning added during earlier restoration work.[15] The familiar black-and-white colour scheme is a fashion introduced by the Victorians; originally the oak beams would have been untreated and left to age naturally to a silver colour, and the rendered infill painted ochre.[29] In 1977 it was discovered that the stone slabs on the roof of the south range had become insecure, and work began on a six-phase programme of structural repairs.[30] Replacement timbers were left in their natural state.[31]

House

The 100-year construction of Little Moreton Hall coincided with the English Renaissance, but the house is resolutely medieval in design,[12] apart from some Renaissance decoration such as the motifs on the Gatehouse,[17] Elizabethan fireplaces, and its "extravagant" use of glass.[32] It is timber-framed throughout except for three brick chimneybreasts and some brick buttressing added at a later date.[12]

Simon Jenkins has described Little Moreton Hall as "a feast of medieval carpentry",[33] but the building technique is unremarkable for Cheshire houses of the period – an oak framework set on stone footings. Diagonal oak braces that create chevron and lozenge patterns adorn the façades.[34] The herringbone pattern with quatrefoils present at the rear, which can also be seen at Haslington and Gawsworth Halls, is a typical feature of 15th-century work, while the lozenge patterns, continuous middle rail and lack of quatrefoils in the front façade are typical of 16th-century early Elizabethan work.[35] The south range containing the gatehouse, the last to be completed, has lighter timbers with a greater variety of patterns.[15] The timber frame is completed by rendered infill and Flemish bond brick, or windows.[36] The windows contain 30,000 leaded panes known as quarries, set in patterns of squares, rectangles, lozenges, circles and triangles, complementing the decoration on the timber framing.[34] Much of the original 16th-century glazing has survived and shows the colour variations typical of old glass.[15] Old scratched graffiti is visible in places.[37][lower-alpha 9] The older parts of the roof frame are decorated,[38] and the brickwork of some of the chimneys has diapering in blue brick.[39]

The house stands on an island surrounded by a 33-foot (10 m) wide moat,[6][lower-alpha 10] which was probably dug in the 13th or 14th century to enclose an earlier building on the site.[1] There is no evidence that the moat served any defensive purpose, and as with many other moated sites it was probably intended as a status symbol. A sandstone bridge leads to a gatehouse in the three-storey south range,[6] which has each of its two upper floors jettied out over the floor beneath.[41] As is typical of Cheshire's timber-framed buildings the overhanging jetties are hidden by coving,[42] which has a recurring quatrefoil decoration.[43] The Gatehouse leads to a rectangular courtyard, with the Great Hall at the northern end. The two-storey tower to the left of the Gatehouse contains garderobes, which empty directly into the moat.[44] Architectural historian Lydia Greeves has described the interior of Little Moreton Hall as a "corridor-less warren, with one room leading into another, and four staircases linking different levels".[18] Some of the grander rooms have fine chimneypieces and wood panelling, but others are "little more than cupboards".[18] The original purpose of some of the rooms in the house is unknown.[14]

Ground floor

- Great Hall

- Parlour

- Garderobe

- Private staircase

- Withdrawing Room

- Exhibition Room

- Chapel

- Chancel

- Corn Store

- Gatehouse

- Bridge

- Garderobe

- Brew-house (now public toilets)

- Shop

- Restaurant

- Screens passage

- Hall porch

- Courtyard

- Kennel

The Great Hall at the centre of the north range is entered through a porch and screens passage, a feature common in houses of the period, designed to protect the occupants from draughts. As the screens are now missing, they may have been free-standing like those at Rufford Old Hall.[45] The porch is decorated with elaborate carvings.[15] The Great Hall's roof is supported by arch-braced trusses,[14] which are decorated with carved motifs including dragons.[46] The floor, now flagged, would probably originally have been rush-covered earth, with a central hearth. The gabled bay window overlooking the courtyard was added in 1559. The original service wing to the west of the Great Hall, behind the screens passage, was rebuilt in 1546,[14] and housed a kitchen, buttery and pantry.[41] A hidden shaft was discovered during a 19th-century investigation of two secret rooms above the kitchen, connecting them to a tunnel leading to the moat, the entrance to which has since been filled in.[47] The west range now houses the gift shop and restaurant.

A doorway behind where the family would have sat at the far end of the hall leads to the Parlour, known as the Little Parlour in surviving 17th-century documents. Together with the adjoining Withdrawing Room and the Great Hall, the Parlour is structurally part of the original building.[48] The wooden panelling is a Georgian addition, behind which the original painted panelling was discovered in 1976.[49] The decoration consists of painted imitations of marble and inlay,[15] and Biblical scenes, some of which were painted directly onto the plaster and others on paper that was then pasted to the wall. "Crudely drawn" but nevertheless "elaborate", the paintings tell the story of Susanna and the Elders from the Apocrypha,[49] a "favourite Protestant theme".[4] The Moreton family's wolf head crest and the initials "J.M." suggest a date before John Moreton's death in 1598. Similar painted decoration is found in other Cheshire houses of the late 16th and early 17th centuries.[15]

A private staircase between the Parlour and the Withdrawing Room leads to the first floor. The Withdrawing Room has 16th-century carved wooden panelling, and a wooden ceiling with moulded coffering, which probably dates from 1559 when the Great Hall ceiling was added.[15] The bay window in this room was also added in 1559, at the same time as the one in the Great Hall. The pair of windows bear the following inscription underneath their gables:

God is Al in Al Thing: This windous whire made by William Moreton in the yeare of Oure Lorde MDLIX. Rycharde Dale Carpeder made thies windous by the grac of God.[19]

The wolf head crest also appears in the late 16th-century stained glass of the Withdrawing Room.[49] The chimneypiece in this room is decorated with female caryatids and bears the arms of Elizabeth I; its plaster would originally have been painted and gilded, and traces of this still remain.[15]

William Moreton III used what is today known as the Exhibition Room as a bedroom in the mid-17th century; it is entered through a doorway from the adjoining Withdrawing Room. Following William's death in 1654 his children Ann, Jane and Philip divided the house into three separate living areas. Ann, whose accommodation was in the Prayer Room above, then used the Exhibition Room as a kitchen. The adjoining Chapel, begun in 1508,[50] is accessible by a doorway from the courtyard. The Chapel contains Renaissance-style tempera painting, thought to date from the late 16th century.[51] Subjects include passages from the Bible.[15] The chancel was probably a later addition dating from the mid-16th century.[50] It is separated from the nave by an oak screen and projects eastwards from the main plan of the house, with a much higher ceiling.[46] The stained glass in the east wall of the chancel is a 20th-century addition installed by Charles Abraham, the last private owner of Little Moreton Hall, as a parting gift on his transfer of ownership to the National Trust.[52]

The Corn Store adjacent to the Chapel may originally have been used as accommodation for a gatekeeper or steward. By the late 17th century it had been converted into a grain store by raising the floor to protect its contents from damp. Five oak-framed bins inside may have held barley for the Brew-house,[52] which is now used as a toilet block.

First floor

- Great Hall

- Prayer Room

- Chancel

- Guests' Hall

- Porch Room

- Garderobes

- Guests' Parlour

- Brew-house Chamber

The Guests' Hall and its adjoining Porch Room occupy the space above the entrance to the courtyard and the Gatehouse. They can be accessed either through a doorway from the adjacent Prayer Room or via a staircase at the south end of the courtyard leading to the Long Gallery on the floor above. The first-floor landing leads to a passageway between the Guests' Hall and the Guests' Parlour, and to the garderobe tower visible from the front of the house. A doorway near the entrance to the Guests' Parlour allows access to the Brew-house Chamber, which is above the Brew-house. The Brew-house Chamber was probably built as servants' quarters, and originally accessed via a hatch in the ceiling of the Brew-house below.[44]

In the mid-17th century the Guests' Hall was referred to as Mr Booth's Chamber, after the genealogist Jack Booth of Tremlowe, a cousin and family friend of the Moreton's and a regular occupant.[53] Its substantial carved consoles, inserted not just for decorative effect but to support the weight of the Long Gallery above, have been dated to 1660.[54] What is today known as the Prayer Room, above the Chapel, was originally the chamber of the first William Moreton's daughter Ann, whose maid occupied the adjoining room.[53]

The floors of the rooms on this level are made from lime-ash plaster pressed into a bedding of straw and oak laths, which would have offered some protection against the ever-present risk of fire.[54] All the first-floor rooms in the east range and all except the Prayer Room in the west range are closed to the public, some having been converted into accommodation for the National Trust staff who live on site.[55][56] The Education Room in the east range, above what is today the restaurant, was in the mid-16th century a solar, and is now reserved for use by school groups.[57]

Upper floor

Running the entire length of the south range the Long Gallery is roofed with heavy gritstone slabs,[58] the weight of which has caused the supporting floors below to bow and buckle.[27] Architectural historians Peter de Figueiredo and Julian Treuherz describe it as "a gloriously long and crooked space, the wide floorboards rising up and down like waves and the walls leaning outwards at different angles."[15] The crossbeams between the arch-braced roof trusses were probably added in the 17th century to prevent the structure from "bursting apart" under the load.[59]

The Long Gallery has almost continuous bands of windows along its longer sides to the north and south, and a window to the west; a corresponding window at the east end of the gallery is now blocked.[60] The end tympana have plaster depictions of Destiny and Fortune, copied from Robert Recorde's Castle of Knowledge of 1556.[15][61] The inscriptions read "The wheel of fortune, whose rule is ignorance" and "The speare of destiny, whose rule is knowledge".[62] The Long Gallery was always sparsely furnished, and would have been used for exercising when the weather was inclement and as a games room – four early 17th-century tennis balls have been discovered behind the wood panelling.[44]

The Upper Porch Room leading off the Long Gallery, perhaps originally intended as a "sanctuary from the fun and games",[44] was furnished as a bedroom by the mid-17th century. The fireplace incorporates figures of Justice and Mercy,[15] and its central panel contains the Moreton coat of arms quartered with that of the Macclesfield family, celebrating the marriage of John de Moreton to Margaret de Macclesfield in 1329.[44][lower-alpha 11]

Contents

Only three pieces of the house's original furniture have survived: a large refectory table, a large cupboard described as a "cubborde of boxes" in an inventory of 1599, possibly used for storing spices, and a "great rounde table" listed in the same inventory.[63][64] The refectory table and cupboard are on display in the Great Hall, and the round table in the Parlour, where its octagonal framework suggests that it was designed to sit in the bay window. Except for those pieces, and a collection of 17th-century pewter tableware in a showcase in the west wall of the Great Hall, the house is displayed with bare rooms.[18][63]

Gardens and estate

By the mid-16th century the Little Moreton Hall estate was at its greatest extent, occupying an area of 1,360 acres (550 ha) and including three watermills,[7] one of which was used to grind corn. The contours of the pool used to provide power for the cornmill are still visible, although the mill was demolished in the 19th century.[65] The Moreton family had owned an iron bloomery in the east of the estate since the late 15th century, and the other two mills were used to drive its water-powered hammers. The dam of the artificial pool that provided water for the bloomery's mills, known as Smithy Pool, has survived, although the pool has not. The bloomery was closed in the early 18th century, and the pool and moat were subsequently used for breeding carp and tench. By the mid-18th century the estate's main sources of income came from agriculture, timber production, fish farming, and property rentals.[65]

The earliest reference to a garden at Little Moreton Hall comes from an early 17th-century set of household accounts referring to a gardener and the purchase of some seeds. Philip Moreton, who ran the estate for his older brother Edward in the mid-17th century, left a considerable amount of information on the layout and planting of the area of garden within the moat, to the west of the house. He writes of a herb garden, vegetable garden, and a nursery for maturing fruit trees until they were ready to be transferred to the orchard at the south and east of the house, probably where the orchard is today.[66]

During the 20th century the long-abandoned gardens were replanted in a style sympathetic to the Tudor period. The knot garden was planted in 1972, to a design taken from Leonard Meager's Complete English Gardener, published in 1670.[67] The intricate design of the knot can be seen from one of the two original viewing mounds, common in 16th-century formal gardening, one inside the moat and the other to the southwest.[66] Other features of the grounds include a yew tunnel and an orchard growing fruits that would have been familiar to the house's Tudor occupants – apples, pears, quinces and medlars.[65]

Superstition and haunting

During the last major restoration work, 18 "assorted boots and shoes" were found hidden in the structure of the building, all dating from the 19th century.[68] Concealed shoes were placed either to ward off demons, ghosts or witches, or to encourage the fertility of the female occupants.[69] Like many old buildings, Little Moreton Hall has stories of ghosts; a grey lady is said to haunt the Long Gallery, and a child has reportedly been heard sobbing in and around the Chapel.[70]

Present day

Little Moreton Hall is open to the public from mid-February to December each year. The ground floor of the west range has been remodelled to include a restaurant and a tearoom whilst a new building houses the visitor reception and shop.[71] Services are held in the Chapel every Sunday from April until October.[72][73] In common with many other National Trust properties, Little Moreton Hall is available for hire as a film location; in 1996 it was one of the settings for Granada Television's adaptation of Daniel Defoe's Moll Flanders, The Fortunes and Misfortunes of Moll Flanders.[74]

See also

References

Notes

- The house was known as Old Moreton Hall during the period when it was rented out to tenant farmers, from the late 1670s onwards.[1]

- Little Moreton Hall is built on the site of a much earlier medieval building, the remains of which are believed to have survived in the ground under the present house.[6]

- Many older sources, such as Pevsner & Hubbard (1971), suggest that building work began in c. 1450, or towards the end of the 15th century, but tree-ring analysis shows that the earliest parts of the house were built in the first decade of the 16th century.[7][12]

- The floor had been removed by 1807.[14]

- Comparing GDP per capita of £3,000 and £4,000 in 1654 with 2010.

- Elizabeth Moreton (1821–1912) had become a Sister of the Community of St John Baptist in 1853.[24]

- The house has never been sold throughout its 500-year history.[9]

- Comparing average earnings of 6d in 1912 with 2010.

- One inscription reads: "Man can noe more/know weomen's mind/by kaire/Than by her shadow/hede ye what clothes/Shee weare".

- The site is marshy, which is at least in part why the oak beams of the house's timber frame stand on sandstone blocks. The moat is kept filled by the high water table.[40]

- Margaret de Macclesfield was an heiress to the estate of John de Macclesfield.[44]

Citations

- "Little Moreton Hall's Survival", National Trust, archived from the original on 24 December 2012, retrieved 22 November 2012

- "How to get here", Little Moreton Hall, National Trust, retrieved 1 February 2018

- Fedden & Joekes (1984), p. 19

- Greeves (2006), p. 226

- Historic England, "Little Moreton Hall (1161988)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 4 August 2012

- Historic England, "Little Moreton Hall moated site and outlying prospect mound (1011879)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 4 August 2012

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 28

- Angus-Butterworth (1970), pp. 177–78

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 2

- Angus-Butterworth (1970), pp. 178–79

- Angus-Butterworth (1970), p. 180

- Hartwell et al. (2011), p. 433

- Lake & Hughes (2006), pp. 9–15

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 9

- de Figueiredo & Treuherz (1988), pp. 119–22

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 4

- Fedden & Joekes (1984), p. 155

- Greeves (2008), p. 201

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 29

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 40

- Lake & Hughes (2006), pp. 37–38

- Officer, Lawrence H. (2009), "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present", MeasuringWorth, archived from the original on 24 November 2009, retrieved 25 November 2012

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 38

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 42

- "Little Moreton Hall, Cheshire", Royal Institute of British Architects, archived from the original on 13 October 2007, retrieved 13 November 2007

- Coward (2010), p. 329

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 44

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 45

- Lipscomb (2012), loc. Little Moreton Hall

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 46

- McKenna (1994), p. 36

- Jenkins (2003), p. 90

- Jenkins (2003), p. 69

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 7

- McKenna (1994), p. 13, Fig. 27

- "Little Moreton Hall", Pastscape, retrieved 26 April 2008

- Angus-Butterworth (1970), p. 189

- McKenna (1994), p. 9

- Angus-Butterworth (1970), p. 185

- Fortey (2010), p. 21

- Goodall, John, "The Great Hall", BBC, retrieved 13 November 2007

- Pevsner & Hubbard (2003), p. 21

- Hartwell et al. (2011), p. 435

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 21

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 10

- Angus-Butterworth (1970), p. 186

- Smith (2010), p. 270

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 11

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 13

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 15

- Fedden & Joekes (1984), p. 156

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 17

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 23

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 22

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 5

- "A Marriage Made in Little Moreton Hall", Cheshire Life, 20 April 2011, retrieved 17 November 2012

- "Virtual Tour", National Trust, archived from the original on 13 March 2013, retrieved 24 November 2012

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 6

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 18

- Hartwell et al. (2011), p. 434

- Lake & Hughes (2006), pp. 18–21

- Angus-Butterworth (1970), p. 187

- Lake & Hughes (2006), pp. 10–14

- Bilsborough (1983), pp. 133

- Lake & Hughes (2006), p. 27

- Lake & Hughes (2006), pp. 24–25

- Fedden & Joekes (1984), pp. 155, 257

- Hoggard (2004), p. 180

- Hoggard (2004), pp. 178–79

- Jones, Richard, "Ghosts of the North Midlands", Haunted Britain, retrieved 28 October 2012

- "Little Moreton Hall", National Trust, archived from the original on 26 April 2011, retrieved 30 April 2011

- "Sunday service at Little Moreton Hall's Chapel", National Trust, archived from the original on 24 December 2012, retrieved 3 November 2012

- Duckworth & Sankey (2006), p. 110

- "Moll Flanders", perioddramas.com, retrieved 10 November 2012

Bibliography

- Angus-Butterworth, Lionel M. (1970) [1932], Old Cheshire Families and their Seats, E. J. Morten, ISBN 978-0-901598-17-2

- Bilsborough, Norman (1983), The Treasures of Cheshire, North West Civic Trust, ISBN 978-0-901347-35-0

- Coward, Thomas Alfred (2010) [1926], Picturesque Cheshire, Methuen, ISBN 978-1-176-93359-0

- de Figueiredo, Peter; Treuherz, Julian (1988), Cheshire Country Houses, Phillimore, ISBN 978-0-85033-655-9

- Duckworth, Katie; Sankey, Charlotte (2006), 101 Family Days Out, National Trust Books, ISBN 978-1-905400-02-7

- Fedden, Robin; Joekes, Rosemary (1984), The National Trust Guide, The National Trust, ISBN 978-0-224-01946-0

- Fortey, Richard (2010), The Hidden Landscape: A Journey into the Geological Past, Bodley Head, ISBN 978-1-84792-071-3

- Greeves, Lydia (2006), History and Landscape: The guide to National Trust properties in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (new ed.), National Trust Books, ISBN 978-1-905400-13-3

- Greeves, Lydia (2008), Houses of the National Trust, National Trust Books, ISBN 978-1-905400-66-9

- Hartwell, Clare; Hyde, Matthew; Hubbard, Edward; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2011) [1971], Cheshire, The Buildings of England, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-17043-6

- Hoggard, Brian (2004), "The archaeology of counter-witchcraft and popular magic", in Davies, Owen; De Blécourt, William (eds.), Beyond the Witchtrials: Witchcraft and Magic in Enlightenment Europe, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-6660-3

- Jenkins, Simon (2003), England's Thousand Best Houses, Studio Books, ISBN 978-0-670-03302-7

- Lake, Jeremy; Hughes, Pat (2006) [1995], Little Moreton Hall (revised ed.), The National Trust, ISBN 978-1-84359-085-9

- Lipscomb, Suzannah (2012), A Visitor's Companion to Tudor England, Ebury Digital

- McKenna, Laurie (1994), Timber Framed Buildings in Cheshire, Cheshire County Council, ISBN 978-0-906765-16-6

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Hubbard, Edward (2003) [1971], Cheshire, The Buildings of England, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-071042-7

- Smith, Stephen (2010), Underground England: Travels Beneath Our Cities and Country, Abacus, ISBN 978-0-349-12038-6

Further reading

- Garnett, Oliver (2013), Little Moreton Hall, National Trust, ISBN 978-1-84359-085-9