Little blue heron

The little blue heron[note 1] (Egretta caerulea) is a small heron of the genus Egretta. It is a small, darkly colored heron with a two-toned bill. Juveniles are entirely white, bearing resemblance to the snowy egret. During the breeding season, adults develop different coloration on the head, legs, and feet.

| Little blue heron | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult little blue heron in Cananeia, São Paulo, Brazil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Ardeidae |

| Genus: | Egretta |

| Species: | E. caerulea |

| Binomial name | |

| Egretta caerulea | |

| |

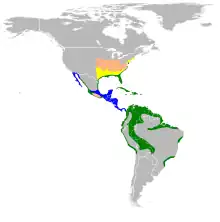

| Distribution of Egretta caerulea: breeding non-breeding year-round migration | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ardea caerulea Linnaeus, 1758 | |

They have a range that encompasses much of the Americas, from the United States to northern South America. Some populations are migratory. Climate change will probably cause their distribution to spread north. They can be found in both saltwater and freshwater ecosystems. Their preference for either one depends on where they live.

Nesting behaviors are documented by numerous sources. The adults build nests in trees, in colonies with other bird species. The number of eggs laid varies from place to place. The young mature quickly, requiring little attention from adults after about nineteen days of age. Both young and adults are sometimes preyed on by other species. Adults hunt fish, crabs, and other small animals. As with clutch sizes, diet can vary regionally.

The population of E. caerulea is declining. Many possible reasons for this have been proposed. Exposure to heavy metals has been found to have detrimental effects on young birds.

Taxonomy

The little blue heron is part of the family Ardeidae, a group whose members can be found throughout much of the world, including the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Oceania.[3] It was first described as Ardea caerulea by Carl Linnaeus in his 10th edition of Systema Naturae.[4] It is now a member of the genus Egretta.[3] It may be closely related to the snowy egret, another member of its genus, which it greatly resembles when young.[5] Variations of the name include Ardea coerulea, Florida caerulea, and Hydranassa caerulea.[2]

Young birds found in a little blue heron nest in North Dakota, at a site heavily populated by cattle egrets (Bubulcus ibis), which displayed traits of both the former and latter, are believed to be an example of hybridization between the two species.[6] Other species they are known to hybridize with include the tricolored heron, little egret, snowy egret, and black-crowned night heron. Of these four, only the black-crowned night heron is not a member of Egretta.[2]

Description

Males and females have the same coloration. The adults are darkly colored, with purple-maroon heads and blue bodies. During the breeding season, their heads turn dark red. They have two-toned bills, which are a light blue at the base, with black tips. Their eyes are yellow and their legs are greenish. Juveniles are almost completely white, although the upper primaries are somewhat dark in color. Like adults, their bills are two-toned. Immature birds transitioning from the juvenile to adult phase have a combination of light and dark feathers. Both sexes are about 56–74 centimetres (22–29 in), with a wingspan of 100–105 centimetres (39–41 in). They weigh about 397 grams (14.0 oz).[7][8]

The lores, which are normally a dull green become a shade of turquoise. They also develop long plumes on the crest and back, which can stretch 20–30 centimetres (7.9–11.8 in) past the tail. The legs and feet become black.[9] The eggs are typically smooth, light blue, and unmarked. In size, they are about 31.7–43.2 millimetres (1.25–1.70 in), with a weight of around 23.1 grams (0.81 oz).[10]

Distribution and habitat

_juvenile_Cayo.jpg.webp)

Egretta caerulea can be found regularly in the United States, Mexico, Central America, northern South America (including Venezuela, Colombia, and Peru), and numerous Caribbean islands (including Cuba, Jamaica, and Hispaniola). They have been recorded as a vagrant (a species that appears far outside its natural range) in Greenland, Portugal, and South Africa. Whether or not their range is declining is unknown.[1] In the United States, they can be found from Missouri to Virginia to Florida. They are more common in peninsular Florida than the Florida Panhandle.[7] They can occasionally roam as far north as Canada.[3]

Individuals in central Alabama tend to migrate towards South America and the Caribbean, while those from the Mississippi River west travel to Mexico and Central America.[3] One study found that of seven migratory wading bird species, the little blue heron had the greatest mean dispersal distance, of 1,148 kilometres (713 mi).[11]

Future climate change is projected to increase its overall range. If global warming continues at its current rate, by the year 2080, its summer range will have increased by 87%. Of its current range, it is expected to lose only 1%. These gains would spread its summer distribution well into more northern parts of the US, such as Michigan and Minnesota, and even into southern Canada.[5]

The little blue heron can be found in freshwater and marine environments. These include mangrove forests, bogs, swamps, salt marshes, tidal flats, estuaries, streams, and flooded fields.[1][8] They are usually found at low elevations, but can be seen at heights of 3,700 metres (12,100 ft) in the Andes.[9]

In North America, they tend to favor freshwater habitats, while in the Caribbean, they are more often found in saltwater.[5] Towards the southern extent of their range, in Brazil, they are found almost exclusively along the coast, rarely venturing inland at all.[10]

Regional variations

Juveniles in San Blas, in the Mexican state of Nayarit have an atypical color-scheme. In these birds, the top of the head is chestnut colored and the wings tips are much darker. Initially, it was suggested that they may be hybrids, however further study concluded they were most likely a natural variation.[12] No other geographic varieties have been observed.[9]

Behavior and ecology

Little blue herons prefer to stand still and wait when hunting, rather than chase after prey. They walk slowly and search for fish and other prey items, flying to different spots if needed. They tend to move slower than other related species, which can help distinguish them. They are not usually found in large numbers at any body of water. Occasionally, however, they will gather with other herons, especially if they have found a school of fish trapped in shallow water.[8] They sometimes also feeds in grassy fields.[5]

Reproduction and life cycle

During courtship, both males and females practice bill-nibling. Males also use a neck-stretch to attract mates.[13]

Nesting

Little blue herons typically nest in trees alongside other roosting birds.[8] They are colonial nesters (nesting in groups). Examples of species they may nest alongside include the scarlet ibis, yellow-crowned night heron, great egret, black-crowned night heron, and snowy egret.[10]

During nest construction, males bring twigs to females, who use them to build the nest. Both males and females help incubate their clutch.[13] They begin incubation after two eggs have been laid, which will cause any later eggs to hatch out of sync. The chicks that hatch later tend to not receive as much food as early-hatching ones, which limits their growth.[14] Clutch sizes vary significantly throughout their range. In Trinidad, there are usually 2–5 eggs, while in Costa Rica, only 2–4 are laid on average. In North America, the mean is 2.67–4.4. The very lowest values are seen in southeastern Brazil and the US states Florida and Georgia, where no more than three are generally laid.[10]

Young herons are able to start climbing around the branches by their nests at 15 days old.[10] Due to the young age at which they develop motor skills in their legs, the young do not rely on their parents for anything besides feeding after 19 days, at which point the adults begin foraging away from the nest.[14] By 20–25 days, they can climb to the very top of the tree their nest is built on, or even into other trees. They can fly short distances at around 30 days of age (some take 35–38), but will still be dependent on adults for about two weeks after that.[10] It is in their second year of life that juveniles begin to lose their white feathers.[9]

Predation

There is circumstantial evidence that young black-crowned night herons and crab-eating raccoons prey on nestling little blue herons. Adults have been observed driving a yellow-headed caracara away from their nests. In the presence of a Harris' hawk, however, the little blue herons fled.[10]

Parasites

Twenty-four different species of parasitic worms were found on 33 of 35 little blue herons examined in South Florida. These included trematodes, nematodes, acanthocephalans, and one cestode. The most common trematode was Posthodiplostomum macrocotyle, and the most common nematodes were Contracaecum multipapillatum and Contracaecum microcephalum. The acanthocephalan and cestode species could not be identified (in the latter, neither could the genus).[15]

Prey

On the eastern coast of North America, little blue herons primarily feed on fish, however their diet varies significantly throughout their range.[9] In a study of individuals in mangrove forests in southeastern Brazil, 80% of their diet during the breeding season was found to consist of crabs. Compared to the scarlet ibis, the herons preferred arboreal or semi-arboreal species, such as Aratus pisonii and Metasesarma rubripes, while the former preferred to take burrowing species. This demonstrates their different feeding strategies—scarlet ibises being foragers who hunt using their sense of touch and little blue herons being visual hunters.[16] In another mangrove forest in southwestern Puerto Rico, the entire diet was found to consist of fiddler crabs.[17]

Conservation

The little blue heron is listed as a least-concern species by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, although its numbers are decreasing.[1] Historically, they were not hunted for their feathers as much as other heron species due to their lack of visually attractive plumes.[8]

The dangers faced by Egretta caerulea are not well researched. They could include development along coastlines, habitat disturbance, predators, pesticide exposure, and parasites.[7] The metals cadmium and lead have been found to lead to slower growth rates and higher death rates, respectively, of young birds.[18] In Sepetiba Bay, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, little blue herons were found to have relatively high levels of metal contamination in the liver and kidneys.[19]

In areas with cattle egrets, little blue herons have been found to nest for shorter amounts of time, and produce fewer young that survive to adulthood. Cattle egrets only begin pairing when most little blue herons already have eggs or live young in their nests. The former species has been observed stealing twigs from nests of the latter. This behavior sometimes leads to the young falling out of the nest or the cattle egrets removing them.[20]

References

- BirdLife International (2017). "Egretta caerulea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22696944A118857172. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22696944A118857172.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- "Little Blue Heron Egretta caerulea (Linnaeus, C 1758)". Avibase. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Cottrell, G. William; Greenway, James C.; Mayr, Ernst; Paynter, Raymond A.; Peters, James Lee; Traylor, Melvin A.; University, Harvard (1979). Check-list of birds of the world. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 211–212. Archived from the original on 2022-09-30. Retrieved 2022-09-30.

- Linné, Carl von; Salvius, Lars (1758). Caroli Linnaei...Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Vol. 1. Holmiae: Impensis Direct. Laurentii Salvii. p. 143. Archived from the original on 2017-03-25. Retrieved 2022-09-30.

- "Little Blue Heron". Audubon. 13 November 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- Bartos, Alisa J.; Igl, Lawrence; Sovada, Marsha A. (2010). "Observations of Little Blue Herons nesting in North Dakota, and an instance of probable natural hybridization between a Little Blue Heron and a Cattle Egret". The Prairie Naturalist. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Little blue heron". Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- "Little Blue Heron". The Cornell Lab. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- "Little Blue Heron". Heron Conservation. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Olmos, Fábio; Silva e Silva, Robson (2002). "Breeding Biology of the Little Blue Heron (Egretta Caerulea) in Southeastern Brazil" (PDF). Ornitologia Neotropical. The Neotropical Ornithological Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- Melvin, Stefani L.; Gawlik, Dale E.; Scharff, T. (1999). "Long-Term Movement Patterns for Seven Species of Wading Birds". Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology. 22 (3): 411–416. doi:10.2307/1522117. JSTOR 1522117. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- Dickerman, Robert W.; Parkes, Kenneth C. (1963). "Notes on the Plumages and Generic Status of the Little Blue Heron". The Auk. 85 (3): 437–440. doi:10.2307/4083292. JSTOR 4083292. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- Rodgers, James A. (April 1980). "Little Blue Heron Breeding Behavior". The Auk. 97 (2). Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Werschkul, David F. (January 1979). "Nestling Mortality and the Adaptive Significance of Early Locomotion in the Little Blue Heron". The Auk. 96 (1). Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Sepúlveda, María Soledad; Spalding, Marilyn G.; Kinsella, John M.; Forrester, Donald J. (January 1996). "Parasitic Helminths of the Little Blue Heron, Egretta caerulea, in Southern Florida". Comparative Parasitology.

- Olmos, Fábio; Silva E Silva, Robson; Prado, Ariadne (April 2001). "Breeding Season Diet of Scarlet Ibises and Little Blue Herons in a Brazilian Mangrove Swamp". Waterbirds. 24 (1): 50–57. doi:10.2307/1522243. JSTOR 1522243. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Collazo, Jaime A.; Miranda, Leopoldo (1997). "Food Habits of 4 Species of Wading Birds (Ardeidae) in a Tropical Mangrove Swamp". Colonial Waterbirds. 20 (3): 413–418. doi:10.2307/1521591. JSTOR 1521591. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Spahn, S. A.; Sherry, T. W. (1999-10-01). "Cadmium and Lead Exposure Associated with Reduced Growth Rates, Poorer Fledging Success of Little Blue Heron Chicks (Egretta caerulea) in South Louisiana Wetlands". Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 37 (3): 377–384. doi:10.1007/s002449900528. ISSN 1432-0703. PMID 10473795. S2CID 30144426. Archived from the original on 2022-10-03. Retrieved 2022-09-30.

- Ferreira, Aldo Pacheco (December 2010). "Estimation of heavy metals in little blue heron (Egretta caerulea) collected from sepetiba bay, rio de janeiro, brazil". Brazilian Journal of Oceanography. 58 (4): 269–274. doi:10.1590/S1679-87592010000400002. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- Werschkul, David F. (1978). "Observations on the Impact of Cattle Egrets on the Reproductive Ecology of the Little Blue Heron". Proceedings of the Colonial Waterbird Group. 1: 131–138. doi:10.2307/1520910. JSTOR 1520910. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

Notes

- Also known as the garceta azul in Spanish.[2]

External links

- Field guide on Flickr

- Florida Bird Sounds - Florida Museum of Natural History

- Little blue heron photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Little blue heron species account at Neotropical Birds (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)