Spix's macaw

Spix's macaw (Cyanopsitta spixii), also known as the little blue macaw, is a macaw species that was endemic to Brazil. It is a member of tribe Arini in the subfamily Arinae (Neotropical parrots), part of the family Psittacidae (the true parrots). It was first described by German naturalist Georg Marcgrave, when he was working in the State of Pernambuco, Brazil in 1638 and it is named for German naturalist Johann Baptist von Spix, who collected a specimen in 1819 on the bank of the Rio São Francisco in northeast Bahia in Brazil. This bird has been completely extirpated from its natural range, and following a several-year survey, the IUCN officially declared it extinct in the wild in 2019.

| Spix's macaw | |

|---|---|

| |

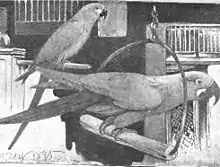

| Adult in Vogelpark Walsrode, Germany in 1980 (approx) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittacidae |

| Tribe: | Arini |

| Genus: | Cyanopsitta Bonaparte, 1854 |

| Species: | C. spixii |

| Binomial name | |

| Cyanopsitta spixii (Wagler, 1832) | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

The bird is a medium-size parrot weighing about 300 grams (11 oz), smaller than most of the large macaws. Its appearance is various shades of blue, with a grey-blue head, light blue underparts, and vivid blue upperparts. Males and females are almost identical in appearance; however, the females are slightly smaller.

The species inhabited riparian Caraibeira (Tabebuia aurea) woodland galleries in the drainage basin of the Rio São Francisco within the Caatinga dry forest climate of interior northeastern Brazil. It had a very restricted natural habitat due to its dependence on the tree for nesting, feeding and roosting. It feeds primarily on seeds and nuts of Caraiba and various Euphorbiaceae (spurge) shrubs, the dominant vegetation of the Caatinga. Due to deforestation in its limited range and specialized habitat, the bird was rare in the wild throughout the twentieth century. It has always been very rare in captivity, partly due to the remoteness of its natural range.

It is listed on CITES Appendix I, which makes international trade prohibited except for legitimate conservation, scientific or educational purposes. The IUCN regard the Spix's macaw as extinct in the wild. Its last known stronghold in the wild was in northeastern Bahia, Brazil and sightings were very rare. After a 2000 sighting of a male bird, the next and last sighting was in 2016.[4] The species is now maintained through a captive breeding program at several conservation organizations under the aegis of the Brazilian government. One of these organizations, the Association for the Conservation of Threatened Parrots (ACTP), moved birds back from Germany to Brazil in 2020 as part of their plan to release Spix's macaws back into the wild. The Brazilian Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio) is conducting a project Ararinha-Azul with an associated plan to restore the species to the wild as soon as sufficient breeding birds and restored habitat are available.

Taxonomy

Spix's macaw is the only known species of the genus Cyanopsitta. The genus name is derived from the Ancient Greek kuanos meaning "blue" and psittakos meaning "parrot".[6] The species name spixii is a Latinized form of the surname "von Spix", hence Cyanopsitta spixii means "blue parrot of Spix".[6] The genus Cyanopsitta is one of six genera of Central and South American macaws in the tribe Arini, which also includes all the other long-tailed New World parrots. Tribe Arini together with the short-tailed Amazon and allied parrots and a few miscellaneous genera make up subfamily Arinae of Neotropical parrots in family Psittacidae of true parrots.[7][8]

In 1638 Georg Marcgrave was the first European naturalist to observe and describe the species; however, it is named for Johann Baptist von Spix, who collected the type specimen in April 1819 in Brazil, but gave it the misnomer Arara hyacinthinus not realizing till later that the name collided with Psittacus hyacinthinus, the name assigned to the hyacinth macaw described by John Lathan in 1790.[9] Spix's mistake was noticed in 1832 by German Professor of Zoology Johann Wagler, who realized that the 1819 specimen was smaller and a different colour from the hyacinth macaw and he designated the new species as "Sittace spixii". It wasn't until 1854 that naturalist Prince Charles Bonaparte properly placed it in its own genus, designating the bird Cyanopsitta spixi [sic],[10] based on important morphological differences between it and the other blue macaws.[11] It was listed as Cyanopsittacus spixi [sic] by Italian zoologist Tommaso Salvadori in his 1891 Catalog of the Birds in the British Museum.[12]

Naturalists have noted the Spix's similarity to other smaller members of tribe Arini based on general morphology as long ago as Rev. F.G. Dutton, president of the Avicultural Society U.K. in 1900: "it's more like a conure" ('conure' is not a defined taxon – in Dutton's time, it referred to the archaic genus Conurus; today those would be among the smaller non-macaw parakeets in Arini).[13] Brazilian ornithologist Helmut Sick stated in 1981: "Cyanopsitta spixii...is not a real macaw"[Notes 1]. (Sick's remark was in the context of an article on Lear's macaw, a larger blue macaw. He recognized, as Spix had not 150 years before, that C. spixii is notably different from the larger macaws).

The morphology-based taxonomy of C. spixii, intermediate between the macaws and the smaller Arini, has been confirmed by recent molecular phylogenetic studies. In a 2008 molecular phylogenetic study of 69 parrot genera,[15] the clade diagrams indicate that C. spixii split from the ancestral parakeets before the differentiation of the modern macaws. However, not all of the macaw genera were represented in the study. The study also states that diversification of the Neotropical parrot lineages occurred starting 33 mya, a period roughly coinciding with the separation of South America from West Antarctica. The author notes that the study challenges the classification of British ornithologist Nigel Collar in the encyclopedic Handbook of the Birds of the World, volume 4 (1997).[8] A 2011 study by the same authors which includes key genera of macaws further elucidates the macaw taxonomy: the clade diagram of that study places C. spixii in a clade including the macaw genera which is sister to a clade containing the Aratingas and other smaller parakeets. Within the macaw clade, C. spixii was the first taxon to diverge from the ancestral macaws; its nearest relatives are the red-bellied macaw (Orthopsittaca manilata) and the blue-headed macaw (Primolius couloni).[16]

Description

Spix's macaw is easy to identify being the only small blue macaw and also by the bare grey facial skin of its lores and eyerings.[17] It is about 56 cm (22 in)[17] long including tail length of 26–38 cm (10–15 in).[18] It has a wing length of 24.7–30.0 cm (9.7–11.8 in).[17] The external appearance of adult male and female are identical;[17] however, the average weight of captive males is about 318 g (11.2 oz) and captive females average about 288 g (10.2 oz).[18] Its plumage is grey-blue on the head, pale blue on the underparts, and vivid blue on the upperparts, wings and tail.[19] The legs and feet are brownish-black. In adults the bare facial skin is grey, the beak is entirely dark grey, and the irises are yellow.[17] Juveniles are similar to adults, but they have pale grey bare facial skin, brown irises, and a white stripe along the top-center of their beaks (along the culmen).[17]

Behaviour

Diet

In the wild, the most common seeds and nuts consumed by Spix's were from Pinhão (Jatropha pohliana var. mollissima) and Favela (Cnidoscolus phyllacanthus). However these trees are colonizers, not native to the bird's habitat, so they could not have been historical staples of the diet.[20]

Its diet also included seeds and nuts from Joazeiro (Ziziphus Joazeiro), Baraúna (Schinopsis brasiliensis), Imburana (Commiphora leptophloeos or Bursera leptophloeos), Facheiro (Pilosocereus piauhyensis), Phoradendron species, Caraibeira (Tabebuia caraiba), Angico (Anadenanthera macrocarpa), Umbu (Spondias tuberosa) and Unha-de-gato (Acacia paniculata). Reports from previous Spix's macaw researchers seem to add another two plants to the list: Maytenus rigida and Geoffroea spinosa. Combretum leprosum may also be a possibility.[18]

Reproduction

Captive bred Spix's macaws reach sexual maturity at seven years of age. A paired female born at the Loro Parque Fundación laid eggs at the age of five years, but these were infertile.[21] It is suspected that late maturity in captivity may be due to inbreeding or other artificial environmental factors, as other parrots of similar size reach sexual maturity in two to four years. In the wild, mating involves elaborate courtship rituals, like feeding each other and flying together. This process is known to possibly take several seasons in other large parrots, and it may also be the case for the Spix's. They make their nests in the hollows of large mature Caraibeira trees, and reuse the nest year after year. The breeding season is November to March, with most eggs hatching in January to coincide with the start of the Caatinga January to April rainy season. In the wild, Spix's were believed to lay three eggs per clutch; in captivity, the average number is four eggs, and can range from one to seven.[18] Incubation period is 25–28 days and only the female performs incubation duties. The chicks fledge in 70 days and are independent in 100–130 days.[18]

The mating call of Spix's macaw can be described as the sound "whichaka". The sound is made by creating a low rumble in the abdomen bringing the sound up to a high pitch.[18] Its voice is a repeated short grating. It also makes squawking noises.[22]

Its lifespan in the wild is unknown; the only documented bird (the last wild male), was older than 20 years. The eldest bird in captivity died at age 34 years.[18]

Distribution and habitat

Various accounts relate that the birds were more common in Pernambuco than in Bahia through the 1960s but not later.[23] Spix's macaw was most recently (1974–1987) known in the Río São Francisco valley, in northeastern Brazil, principally in the basins on the south side of the river in the State of Bahia. In 1974, ornithologist Helmut Sick, based on information from traders and trappers, extended the possible range of the Spix's macaw to embrace the northeastern part of the state of Goias and the southern part of the state of Maranhao.[24] Other ornithologists reporting the bird in various parts of the state of Piaui further extended the range to a vast area of the dry interior of northeast Brazil.[20]

Study of the lone bird discovered at Melância creek in 1990 revealed substantive information about its habitat. It had been previously assumed that the Spix's macaw had a vast range in the interior of Brazil embracing several different habitat types, including buriti palm swamps, cerrado, and dry Caatinga. But the evidence collected in Melância Creek indicated that the Spix's macaw was a specially adapted inhabitant of the disappearing woodland galleries.[25] Ornithologist Tony Silva mentions that "where Caraibeiras have been felled, as in the Pernambuco side of the São Francisco River, the species has disappeared".[26]

Much remains uncertain about the extent of the bird's original range, because most of its woodland habitat was cleared before naturalists observed either the birds or the Caraiba nesting sites. The historical range is now believed to have encompassed portions of the states of Bahia and Pernambuco in a 50 km (31 mi) wide corridor along a 150–200 km (93–124 mi) stretch of the Rio São Francisco between Juazeiro (or possibly Remanso) and Abaré.[23] Previous observations of the birds from further west are very difficult to explain but conceivably stem from either escaped captive birds or more likely the misidentification of another species such as red-bellied macaw (Orthopsittaca manilatus).[20]

The Caatinga vegetation of northeastern Bahia (which hosts the Spix habitat) is stunted trees, thorny shrubs and cacti, dominated by plants of the family Euphorbiaceae. This macaw lived in the hottest and driest part of the "Caatinga" within Caraiba, or Caribbean trumpet tree (Tabebuia caraiba) woodland galleries. The Caraibeira constitutes a microclimate within the Caatinga. The existing galleries are fringes of unique woodland extending a maximum of 18 m (59 ft) to either side along a series of seasonal waterways at least 8 m wide in the Rio São Francisco drainage basin.[20] All T. caraiba woodland was recorded in the middle and lower levels of the creek system where fine alluvial deposits were present. The character of the galleries is tall (8m) evenly spaced Caraibeira trees, ten per hundred meters, interspersed with low scrub and desert cacti. Large mature trees of this species (and apparently no other) provided the nesting hollows of Spix's macaws, as well as shelter and their seedpods, food for the species.[20]

Notable among the seasonal waterways are Riacho Melância watershed 30 km south of Curaçá, where the last known wild Spix's macaw nest was located, adjacent Riacho Barra Grande, and Riacho da Vargem ~100 km to the north near Abaré all in the State of Bahia south of Rio São Francisco. In 1990, these were all that remained of what was once believed to be a vast filigree of creekside Caraibeira woodland extending 50 km into the Caatinga on either side of the Rio São Francisco along a significant stretch of its middle reaches.[27] There is also one confirmed site, since cleared, along Brígida Creek on the north shore of Rio São Francisco in Pernambuco.[28]

History

The species appears to have been seen and described – "MARACANA Brasiliensibus, avis Psittaco planè similis (cuius & species) sed maior, plumae totius ex gryseo subcoerulescunt, clamat ut Psittacus. Fructus amat, Murucuia imprimis. (Translation: "Brazilian parrot, bird very similar to Psittacus [ grey parrot ] but larger, the entire plumage is ashy-bluish, calls like a parrot. Fruit it loves, especially Passionfruit.") – by the German naturalist Georg Marcgrave when he worked in Pernambuco in 1638.[29]

Spix's macaw is named for German naturalist Johann Baptist von Spix, who collected the first specimen in April 1819 near the São Francisco River in the vicinity of Juazeiro[30][31] [Notes 2] Recent authorities cite the type locality as Curaca,[35][36][37] but others say the locality can't be known with certainty.[38][Notes 3]. Spix wrote: "habitat gregarius, rarissimus licet, propre Joazeiro in campis riparüs fluminis St. Francisci, voce tenui insignis" ("it lives in flocks, although very rare, near Joazeiro in the region bordering the rio São Francisco, [and is] notable for its thin voice").[30]

The next reported sighting of the bird wasn't for 84 years, in 1903 by Othmar Reiser of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, 400 kilometres (250 mi) west of Juazeiro at Lagoa de Parnaguá (lake at Parnagua) in the State of Piaui. (What we now know about its habitat and probable range casts doubt on this observation[39]) Reiser had also seen one in captivity at a railway station in Remanso. These observations resulted in an early supposition of a vast potential range for the species in the dry interior of the northeast.[25]

With the passage of the Brazil Wildlife Protection Act in 1967, Brazil forbade the export of its wildlife, and in 1975 became a party to the CITES treaty. These actions barely affected the illicit bird trade, but Spix owners were forced underground (consequently complicating the later effort to initiate a captive recovery program).[40]

The bird had not been studied in the wild until the 1970s. In 1974, Brazilian ornithologist Helmut Sick observed groups of three and four of the birds near Formosa do Rio Preta in northwest Bahia flying over buriti Palms (Mauritia flexuosa).[41] As recently as 1980, Robert Ridgely (ornithologist) stated that "there is no available evidence indicating a recent decline in numbers." Beginning around 1980, at the very height of the illegal bird trade, traders and trappers removed dozens of Spix's from the wild, and by the early 80s, it was generally believed to be extinct in the wild.[42] Naturalist Dr. Paul Roth conducted field surveys of the bird in the Curacá region from 1985 to 1988. Roth found only 5 birds in 1985, three in 1986, and only two after May 1987.[43]

Two of the birds were captured for trade in 1987. A single male, paired with a female blue-winged macaw, was discovered at the site in 1990. A female Spix's macaw released from captivity at the site in 1995 was killed by collision with a power line after seven weeks. The last wild male disappeared from the site in October 2000; his disappearance was thought to have marked the extinction of this species in the wild.[19] However, wild Spix's macaws may have been sighted in 2016.[4] While the IUCN Red List views its status as Critically Endangered and possibly extinct in the wild,[1] ornithologist Nigel Collar of BirdLife International, the authority for the IUCN Redlist of birds now calls this bird extinct in the wild.[39]

As of June 2022, a flock of eight Spix' macaws has been released back into the wild and appears to be doing well. Another release for twelve more later occurred in December of the same year.[44]

Decline and extinction in the wild

The bird was already rare by the time of Spix's discovery of it in 1819 following 100 years of intensive burning, logging and grazing of the Caatinga. Centuries of deforestation, human encroachment and agricultural development along the Rio Sao Francisco corridor following European colonization of eastern Brazil preceded its precipitous decline in the latter part of the 20th century. Naturalists surveying its known remaining native habitat in the Curaçá region have estimated that it could have supported no more than about 60 birds at any time in the last 100 years.[45] Contributing factors were the anthropic introduction of invasive and predatory species of black rats, feral cats, mongooses and marmoset monkeys which prey on the eggs and young,[46] and goats, sheep and cattle which destroy the regenerative growth of the woodland trees, particularly the Caraibeira seedlings.[20]

Other recent evidence has shown that anthropic changes that occurred on the northern shore of the São Francisco River, such as a broad scale conversion into agricultural lands and flooding following the construction of Sobradinho Dam starting in 1974, have changed the flora structure and displaced the Spix's macaw away from that portion of its original range.[28]

The decline of the species in the 1970s and early 80s is attributed to hunting and trapping of the birds, unsustainable harvesting of the Caraíba trees for firewood, the construction of the Sobradinho Dam above Juazeiro starting in 1974 that submerged the basin woodlands under an artificial lake,[28] and the northward migration of the Africanized bee, which competes for nesting sites.[27]

Caraiba grows very slowly; most of the trees are 200–300 years old, and there has not been any regenerative growth for the last 50 years. In addition, 45% of the Caatinga dry forest in which the woodland galleries are embedded has been cleared for farms, ranches and plantations. Climate change resulting in desertification of significant parts of the Caatinga has permanently reduced the potential reclaimable habitat.[47]

An analysis in 2018 based on threats, time since last known confirmed records, and patterns of bird extinction suggested that the bird was in all probability extinct in the wild.[48][49] As of 2019, the IUCN classifies the species as extinct in the wild.[1]

Conservation

In the middle 1980s, by the time fieldwork to locate and understand the habitat of the Spix was completed, it was apparent that the Spix must be nearing extinction in the wild.[50] Conservationists realized that a captive breeding program would be necessary to preserve the species. At a meeting in 1987 of conservationist groups including IUCN at Loro Parque (one of the original Spix holders) in Tenerife, Canary Islands (Spain), only 17 captive Spix macaws could be located.[51] Without the attendance of most of the captive Spix holders or involvement of the Brazilian government, little was accomplished.[52]

In 1990, the Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis (IBAMA, Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources) established the Permanent Committee for the Recovery of Spix's Macaw, called CPRAA, and its Ararinha Azul project (Little Blue Macaw project) in order to conserve the species.[25] At that time, the known captive population of Spix's stood at 15, and one in the wild. Early 1990 was the low point for conservation of the Spix.[53] The Permanent Committee was dissolved in 2002 due to irreconcilable differences between the parties involved. In 2004 a committee was re-formed and re-structured under the title of "The Working Group for the Recovery of the Spix's Macaw".[18]

Since 1987, the Loro Parque Foundation financed the field program to protect and study the last wild male, to protect and restore key habitat, and other important actions.[54] In 1997, the Loro Parque Foundation returned the ownership to the Government of Brazil of all the Spix's macaws held in its facilities.[55]

Between 2000 and 2003, most of two large collections of Spix at Birds International in the Philippines and the aviaries of Swiss aviculturist Dr. Hämmerli were purchased by Sheikh Saud bin Muhammed bin Ali Al-Thani of Qatar and became Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation. Under the Sheikh were instituted standards of animal keeping, veterinary care, animal husbandry and stud book records for the conservation of the Spix's.[56]

In 2007 and 2008, two farms totalling 2,780 hectares (6,900 acres) in Curaçá, State of Bahia, Brazil were purchased by the Lymington Foundation (with contributions from ACTP and Parrots International) and Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation. These compose a small but important part of the natural habitat of the Spix, in the vicinity where the last known wild Spix nest existed. Efforts to clear the habitat of introduced predators and restore the natural Caraibeira seedlings and important creek systems are ongoing on the land.[18]

In May 2012, Brazil's ICMBio formulated and published a 5-year National Action Plan (PAN) for conservation and reestablishment of the species in the wild. Highlights of the plan are to increase the captive population to 150 specimens (expected by 2020), build a breeding facility in Brazil within the Spix's native habitat, acquire and restore additional portions of its range, and prepare for its release into the wild between 2017 and 2021.[28] Pursuant to the plan, in 2012, the Brazilian government established NEST, a private aviary near Avaré, State of Sao Paulo, Brazil as a breeding and staging center for eventual release of the Spix into the wild. Birds formerly housed at the Sao Paulo Zoo as well as Loro Parque Foundation and other conservation organizations were relocated to NEST. The Spix's at NEST are owned by the Brazilian government and managed by Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation.[57]

Captive population

_at_Jurong_Bird_Park_in_Singapore.jpg.webp)

The existing captive population is descended from just 7 wild caught founder birds,[58] which are believed to have all come from just two wild nests that existed post 1982:[20] pairs originally owned by Birds International in the Philippines, Dr. Hämmerli in Switzerland, and Wolfgang Keissling (Loro Parque), and a male from the São Paulo Zoo.[58]

In the years since 1987 when naturalists, conservationists and later IBAMA/ICMBio started tracking the Spix, only two sets of birds unknown in 1987 have ever been discovered: Dr. Hämmerli's in 1991, and a single male bird found in Colorado, U.S. in 2002 named Presley.[59] There is no evidence that any others not known in 1987 still exist (though see a cryptic reference to black market dealing in the birds in 1995.)[60]

As of 2022 there are approximately 177 Spix's macaws in captivity. Eighty-three of these are participating in an international breeding program managed by the Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio), the Natural Heritage Branch of the Brazilian Government.[58] Most of these are managed at Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation (AWWP), which purchased the population of Birds International and most of the birds in Dr. Hämmerli's Swiss collection. Other Spixs are located at Loro Parque Foundation, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Association for the Conservation of Threatened Parrots (ACTP) in Berlin, Germany, NEST in Brazil and Pairi Daiza in Belgium.[61] At three of these five conservation organizations (AWWP, ACTP and NEST), a captive breeding program is guiding Spix's macaw a step closer to re-establishment back to its natural habitat in Brazil.[62] (The female at Loro Parque Foundation cannot be bred due to health reasons).[63][64] Both the AWWP and the ACTP have loaned individuals to Jurong Bird Park in Singapore.[65]

The status and locations of 5 Spix's sold to private owners from Dr. Hämmerli's Swiss collection in 1999 are unknown but presumed to be still alive;[66] they are the likely source of the approximately 13 Spix's in the hands of private owner(s) in Switzerland.[58]

In July 2015, the number of Spix's macaws held in captivity participating in the ICMBio recovery program reached 110(NEST:12, ACTP:12, AWWP:86). The count does not include an unverifiable number of birds in private hands.[67]

| Institutions / Locations | Males | Females | Unknown | Total | Bred in captivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation (AWWP), Doha, Qatar | 24 | 36 | 4 | 64 | 37 |

| Association for the Conservation of Threatened Parrots (ACTP), Berlin, Germany | 4 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 5 |

| Loro Parque Foundation (LPF), Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| NEST, Avaré, Brazil | 3 | 7 | 2 | 12 | 2 |

| (private owners), Switzerland | ? | ? | ~13 | ~13 | ~8 |

| Pairi Daiza, Brugelette, Belgium | ? | ? | 18 | 18 | ? |

| Total | 31 | 47 | ~37 | ~115 | ~58 |

Note: table data based on "Al Wabra ICMBio data from June 2013" and Watson, R. (Studbook Keeper) 2011. "Annual Report and Recommendations for 2011: Spix’s Macaw (Cyanopsitta spixii)".

Health and reproduction

The captive population suffers from very low heterozygosity[68] – the original wild caught founder birds were few, closely related in the wild and intensively inbred in captivity – resulting in infertility, and high rate of embryo deaths (at AWWP, only one in six eggs laid is fertile; only two-thirds of those hatch).[58]

For unknown reasons, originally suspected to be bloodline related, captive specimens seemed to have delayed sexual maturity. The youngest pairs to lay fertile eggs were 10 years of age. Other captive breeding issues are that, possibly because of inbreeding, many more hens than cocks are hatched, at least twice as many.[68]

All or nearly all hatched chicks in the breeding program are hand raised by experienced staff, to reduce the risk of losing a scarce live chick (only about one out of ten viable eggs laid hatch).[18] No chick has been lost through weaning.[58] Non-invasive DNA testing of plucked feathers has been introduced to determine the gender of the chicks. The sex of chicks is not determined until they undergo feather development when they reach one to two months of age.[69]

Spix's macaws choose their own mates independently, so best genetic pairings are not guaranteed. Artificially created "pairs" may groom and associate with each other as if they were a pair, but in fact are not mates, and it may take several seasons to determine this. Another complication is that infected birds cannot be paired with uninfected birds, due to risk of spreading viral diseases.[58]

Artificial insemination

Newest developments in captive breeding programs of this species involved assisted reproduction techniques in the Spix's macaw:

In the 2009–2010 breeding season, a research collaboration between Loro Parque Fundación of Tenerife, Canary Islands and the University of Giessen in Germany used a new technique developed for semen collection and tested in many other parrot species on the Spix's macaws. However, artificial insemination was not used in this case.[70]

Scientists from the University of Giessen of the working group of Prof. Dr. Michael Lierz, Clinic for Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians and Fish, developed a novel technique for semen collection and artificial insemination in large parrots.[71] The research team used artificial insemination for the first time ever in the Spix's macaw at Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation in 2012.

In the 2013 breeding season veterinarians and scientists from Parrot Reproduction Consulting, a German veterinary practice focused on parrot reproduction medicine, and Al Wabra developed new specific strategies for semen collection and artificial insemination of the Spix's macaw. These resulted in the world's first egg fertilisation and first chicks of the Spix's macaw as a result of assisted reproduction, performed et al-Wabra Wildlife Preservation. Two chicks were produced and the first chick was called "Neumann" after Daniel Neumann, the veterinarian who performed these inseminations.[72]

Reintroduction program

In 2018, the population of the species numbered approximately 158 individuals and an agreement was signed between the Ministry of the Environment of Brazil and conservation organizations of Belgium (Pairi Daiza Foundation) and Germany (Association for the Conservation of Threatened Parrots) to establish the repatriation of 50 Spix's macaws to Brazil by the first quarter of 2019. The Spix's macaw was reintroduced to the wild in June 2022.[73][74][75]

The project of reintroduction of the Spix's macaw in Brazil included the creation of two protected areas in the state of Bahia: the Wildlife Refuge of Spix's Macaw, in Curaçá, and the Environmental Protection Area of Spix's Macaw, in Juazeiro, with a awareness work done with the local population and the construction of a reproduction and readaptation center.[74]

In August 2018, 146 of the 160 Spix's macaws in the world lived in the Association for the Conservation of Threatened Parrots in Rüdersdorf, (Germany). 120 of them came from Qatar, transferred due to the death of the maintainer of the Al Wabra Wildlife Preserve, Sheikh Saud bin Muhammed Al Thani, in 2014, and the economic embargo imposed to Qatar by Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt and Bahrain, in 2017. The goal of the Association is to produce about 20 macaws per year.[74]

Born in the wild

Between April and July 2021, three Spix's macaw born in the Caatinga region in the state of Bahia in Brazil, twenty years after the declaration of extinction in wild by the Brazilian government. The chicks are from a couple that came from Germany in 2020.[76][77] The Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio), also declared that the species will be reintroduced into nature in the next years.[76]

In aviculture

One of the earliest records (and one of very few at all) of a Spix's macaw in a public zoo was a dramatic display of "the four blues" including Spix's, glaucous, hyacinth, and Lear's macaws in 1900 at the Berlin Zoo.[78]

The bird was exceedingly rare in aviculture, the few being held by wealthy collectors rather than privately as pets. A trickle of Spix's appeared in captivity starting in the late 1800s. The earliest known specimens were three held by the London Zoological Society between 1878 and 1902.[79]

One of the few accounts of the Spix in captivity was given by Rev. F.G. Dutton, president of the Avicultural Society U.K. in 1900: "I have not yet seen a good-tempered Spix ... My Spix, which is really more a Conure than a Macaw, will not look at sop of any sort, except sponge cake given from one's fingers, only drinks plain water, and lives mainly on sunflower seed. It has hemp, millet, and canary, and peanuts, but I do not think it eats much of any of them. It barks the branches of the tree in which it is loose, and may eat the bark. It would very likely be all the better if it would eat bread and milk, as it might then produce some flight feathers, which it never yet has had. But I expect it would not eat any sop, even if I gave it nothing else."[80]

The bird remained rare and highly coveted. The first captive breeding occurred in the 1950s in Brazil, in the aviaries of the late Alvaro Carvalhaes, an aviculturist from Santos. He hatched numerous chicks, some reports say as many as 24, one of which ended up at the Naples Zoo (Italy), where it remained alive until the late 1980s. Most of his birds died of poisoning in the 1970s. Some of these birds were the likely source of rumored Brazilian Spix owners in the 1960s and 1970s.[81]

Bates and Busenbark say that the bird was intelligent and affectionate, talked some, and had no worse proclivity for screaming than Amazons. They also noted that the Spix were spiteful to other birds.[82]

In October 2002, a Spix named Presley was discovered in Colorado, and repatriated to Brazil. This Spix had not been among those known in 1987.[83] Because all known specimens of the Spix's macaw are now in a conservation program run by the Brazilian government, there are now no sources from which the bird may be obtained for the pet trade. Presley died on 25 June 2014 outside São Paulo, at the approximate age of 40.

What appears to be the last Spix discovered in the wild was found on 18 June 2016 in Curaçá, Brazil, however it is speculated that this may have been a bird released from captivity due to fear of the authorities.[84]

The Spix is one of the "four blues", the four species of all blue macaws formerly seen in captivity together including the hyacinth macaw, Lear's macaw, and glaucous macaw (possibly extinct).[85]

In popular culture

In the animated TV series Noah's Island, the "Born to be Wild" episode focuses on Noah, the main character, bringing a breeding pair of Spix's macaws (though they don’t resemble the species in life) to his island from the Amazon rainforest, in the hope that they will breed. At first, the two macaws are both very aggressive and fight with each other, but they eventually make up and fall in love.[86]

In the opener of the Gorgo episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000, Crow finds that his head crown has become a nesting spot for two Spix's macaw eggs. Later in the episode he reveals that the eggs have been taken away by Egg Protective Services after he accidentally made an omelet in front of them.[87]

In the 2011 animated movie Rio, the main characters Blu (Jesse Eisenberg) and Jewel (Anne Hathaway) are the supposed last pair of Spix's macaws in the world (although they are referred to as blue macaws). The movie even references their extinct-in-the-wild status and at one point ornithologist Túlio Monteiro mentions the species' scientific name.[88] In its 2014 sequel Rio 2, it is revealed that they are not the last pair at all, but in actuality other Spix's macaws are thriving secretly in the Amazon rainforest.[89]

In a 2008 episode titled "Wildlife" of Law and Order SVU the bird was included in an international animal smuggling ring. It was found in the purse of a victim who had been mauled by a tiger. References were made to the extreme rarity of the bird and the potential value of it and other endangered species.[90]

Possible rediscovery

On 18 June 2016 one specimen was seen in Curaçá in the Brazilian state of Bahia. On 19 June, the bird was filmed in poor quality although its call was identified as a Spix's macaw. However, Birdlife noted it is possible the individual was a released captive bird.[84]

Notes

- Sick's full remark was: "The Indigo Macaw is the only true macaw in that region. The Little Blue Macaw (Cyanopsitta spixii), which is another endemic from Northeastern Brazil, is not a real macaw, and is not present in this region."[14]

- Juniper[32] says "It was here [on the bank of the Rio Sao Francisco near Joazeiro] that he [Spix] shot a magnificent long-tailed blue parrot for their collection." But George Smith[33] says: "Among the several unique avian specimens that were brought to him[Spix] by his anonymous collectors was a small blue macaw". Juniper sites his source generally as;[34] the Smith article cites no sources.

- The holotype is now stored in Zoologische Staatssammlung München (ZSM), Germany.

References

- "Cyanopsitta spixii ". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. BirdLife International. 2019: e.T22685533A153022606. 2019.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- Spix, Martius (1824–25). Avium Brasiliensium Species Novae, Vol.1 plate XXIII.

- "Spix's Macaw, Star of "Rio," Spotted in the Wild for the First Time in 15 Years". smithsonianmag.com. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Tavares, E. S.; Baker, A. J.; Pereira, S. L.; Miyaki, C. Y. (2006). "Phylogenetic relationships and historical biogeography of neotropical parrots (Psittaciformes: Psittacidae: Arini) inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences". Systematic Biology. 55 (3): 454–70. doi:10.1080/10635150600697390. PMID 16861209.

- Jobling, James A. (2012). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- Joseph, Leo; Toon, Alicia; Schirtzinger, Erin E.; Wright, Timothy F.; Schodde, Richard (2012). "A revised nomenclature and classification for family-group taxa of parrots (Psittaciformes)" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3205: 26–40. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3205.1.2.

- del Hoyo, J., ed. (1997). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 4. Barcelona,Spain: Lynx Editions. pp. 280–339.

- Ellis, Richard (2004). No Turning Back: The Life and Death of Animal Species. New York: Harper Perennial. p. 270. ISBN 0-06-055804-0.

- Bonaparte, Charles (1854). Revue et magasin de zoologie pure et appliquée. Vol. 6. p. 149.

- Juniper, pp. 19–23

- Salvadori, Tommaso (1891). Catalogue of the Birds in the British Museum. Volume XX: Catalog of the Parrots, or Psittaci in the Collection of the British Museum. Illustrated by Keulemans, John Gerrard. p. 150.

- Dutton, F. G. (1900). "President, Avicultural Society U.K.". The Avicultural Magazine.

- Sick, H. (1981). "About the Blue Macaws Especially the Lear's Macaw". In Pasquier, RF (ed.). Conservation of New World Parrots ICBP Parrot Working Group Meeting (Technical Publication 1). St. Lucia: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 439–44. ISBN 9781199061096.

- Wright, T.F.; Schirtzinger, E. E.; Matsumoto, T.; Eberhard, J. R.; Graves, G. R.; Sanchez, J. J.; Capelli, S.; Muller, H.; Scharpegge, J.; Chambers, G. K.; Fleischer, R. C. (2008). "A Multilocus Molecular Phylogeny of the Parrots (Psittaciformes): Support for a Gondwanan Origin during the Cretaceous". Mol Biol Evol. 25 (10): 2141–2156. doi:10.1093/molbev/msn160. PMC 2727385. PMID 18653733.

- Kirchman, Jeremy J.; Schirtzinger, Erin E.; Wright, Timothy F. (2012). "Phylogenetic relationships of the extinct Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis) inferred from DNA sequence Data". The Auk. 129 (2): 197–204. doi:10.1525/auk.2012.11259. S2CID 86659430.

- Forshaw, Joseph M. (2006). Parrots of the World; an Identification Guide. Illustrated by Frank Knight. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09251-6. plate 70.

- "Spix Macaw Fact File 2010". Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation.

- "Species factsheet: Cyanopsitta spixii". BirdLife International (2008). Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- Juniper, T.; Yamashita (March 1991). "The habitat and status of Spix's Macaw Cyanopsitta spixii". Bird Conservation International. 1 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1017/S0959270900000502.

- "News from the Loro Parque Fundación Parrot collection" (2011) Cyanopsitta 99:11

- "Spix's Macaws: Physical Description, Behavior and Calls / Vocalizations | Beauty of Birds". www.beautyofbirds.com. 16 September 2021.

- Collar; et al. (1997). Threatened Birds of the Americas. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-267-5.

- Sick, Helmut (1989). Ornitologia brasileira, uma introducao. Universidada de Brasilia. ISBN 85-230-0087-9.

- Juniper, T. (2002). "The Spix Macaw Recovery Programme". Proceedings 5th International Parrot Convention.

- Silva, Tony (1989). A Monograph of Endangered Parrots. Silvio Mattachione. ISBN 0-9692640-4-6.

- Roth, Paul (1990). "Spix's Macaw – Cyanopsitta spixii. What do we know today about this rare bird?". Caged Bird (3/4).

- ICMBio. "Executive Summary of the National Action Plan for the Spix's Macaw Conservation" (PDF).

- Marcgrave, Georg (1648). Historia Naturalis Brasiliae. Willem Piso. pp. 205–207.

- Spix, Martius (1824–25). Avium Brasiliensium Species Novae. Vol. 1. p. 25.

- von Helmayr, C. E.; der Abhandl, K. B. (1906). "Revision der Spix'schen Typen Brasilianische Vogel". II Kl. XXII Bd. III Abt. Akademie der Weissenshaften: 563–726, Taf. 1, 2.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Juniper, p. 19

- Smith, George (May 1991). "SPIX'S MACAW Ara (Cyanopsitta) spixii". Parrot Society Magazine. XXV: 164–5.

- von Spix, J. B.; von Martius, C. F. P. (1823–1831). "Book seventh, Chapter II". Reise in Brasilien auf Befehl Sr. Majestät Maximilian Joseph I. König von Baiern in den Jahren 1817–1820 gemacht und beschrieben (in German). Vol. 2. München: Verlag M. Lindauer.

- Arndt, T. (1986). Enzyklopädie der Papageien und Sittiche. Horst Müller-Verlag.

- Silva, T. (1989). A Monograph of Endangered Parrots. Silvio Mattachione.

- Juniper; Yamashita (1990). "The Conservation of Spix's Macaw". Oryx. 24 (4): 224–228. doi:10.1017/s0030605300034943.

- Collar, N. (1992). Threatened Birds of the Americas. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Donald, Paul; Collar, Nigel; Marsden, Stuart; Pain, Debbie (2010). Facing Extinction: the World's Rarest Birds and the Race to Save Them. Poyser. pp. 200–208. ISBN 978-0-7136-7021-9.

- Juniper, p. 31

- Sick, H. & Teixeira, D.M. (1979). "Notas sobreaves brasileiras raras ou ameacadas de extincao". Publiçacões Avulsas Museu Nacional (Rio de J.) (62): 1–39.

- Silva, Tony (1994). "Breeding the Spix's Macaw (Cyanopsitta spixii) at Loro Parque, Tenerife". International Zoo Yearbook. 33: 176–180. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.1994.tb03571.x.

- Roth, P. "Spix-Ara. Was wissen wir heute über diesen seltenen Vogel". Papageien (3/90 and 4/90).

- "'Extinct' parrots make a flying comeback in Brazil". the Guardian. 10 July 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- Schischakin, Natasha (June 1999). "The Spix's Macaw Conservation Programmme A Non-extinction Story". Loro Parque Foundation.

- Juniper, p. 239

- Bertram, Wende. "Climate Change, Adaptation and Desertification Control" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- Butchart, Stuart H.M; Lowe, Stephen; Martin, Rob W; Symes, Andy; Westrip, James R.S; Wheatley, Hannah (2018). "Which bird species have gone extinct? A novel quantitative classification approach". Biological Conservation. 227: 9–18. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2018.08.014. S2CID 91481736.

- "Spix's Macaw heads list of first bird extinctions confirmed this decade". BirdLife International. 5 September 2018.

- Juniper, p. 31,81

- Juniper, p. 161

- Juniper, p. 164-65

- Juniper, pp. 169–71

- "Loro Parque Fundación in Brazil to save the world's rarest parrot" (PDF). Cyanopsitta. No. 100. 2010. p. 18.

- "IBAMA dissolves the Spix’s Macaw Recovery Committee" (2002). Cyanopsitta 66:18–19

- Szotek, Mark (10 September 2009). "Sheikh goes from collector to conservationist in effort to save the world's rarest parrot". Mongabay.

- "Spix's Macaw Project Update". Bluemacaws.org. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- "Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation". Awwp.alwabra.com. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- "Parrot Who Was Among Last of Its Kind, Said to Have Inspired 'Rio,' Dies". Nationalgeographic.com. 29 June 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- Christy, Bryan (2008). The Lizard King. Twelve. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-446-58095-3.

- De Leebeeck, Esther (2022). "In het wild uitgestorven blauwe papegaai vliegt weer rond in Brazilië, met dank aan Pairi Daiza". Het Laatste Nieuws.

- Vastag, Brian (4 July 2011). "Qatari sheik takes endangered bird species under his wing". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- Robinson, Emily Lott (2012). "Revisiting Rio Star Presley: Is there hope for the Spix's Macaw?" (PDF). parrots.org.

- "Spix's Macaw Project Update". www.bluemacaws.org.

- "Jurong Bird Park now home to world's rarest blue macaws". CNA.

- Juniper, pp. 213–214

- Kepp, Michael (10 July 2015). "Spix macaw" (PDF). EcoAméricas: 10.

- Watson, Ryan (July 2007). "Managing the World's Largest Population of Spix's Macaws". 33rd Annual Convention of the American Federation of Aviculture (AFA), Los Angeles.

- "Blue for a Boy?". Loro Parque video documentary. BBC.

- "Developing a New Insemination Technique". Loro Parque. 18 April 2012.

- Lierz, Michael; Reinschmidt, Matthias; Müller, Heiner; Wink, Michael; Neumann, Daniel (2013). "A novel method for semen collection and artificial insemination in large parrots (Psittaciformes)". Scientific Reports. 3: 2066. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3E2066L. doi:10.1038/srep02066. PMC 3691562. PMID 23797622.

- James, Bonnie (22 May 2013). "Qatar efforts give hope to rare parrot species". Gulf Times.

- "Spix's macaw returns to skies of Brazil's caatinga after 20+ years". Agência Brasil. 5 June 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- Deutsche Welle (7 August 2018). "O projeto para salvar a ararinha-azul da extinção". DW.COM (in Portuguese). Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- "Dozens of last blue macaws to be reintroduced to Brazil". phys.org. June 2018.

- "Filhotes de ararinhas-azuis nascem no Brasil após 20 anos de extinção". CNN Brazil (in Portuguese). 18 July 2021.

- "Filhotes de ararinhas-azuis nascem na Bahia após 20 anos de extinção no país". O Globo (in Portuguese). 18 July 2021.

- Juniper, Tony (2004). Spix's Macaw: The Race to Save the World's Rarest Bird. Simon and Schuster. p. 55. ISBN 9780743475518.

- Juniper, pp. 25–26

- Dutton, F.G. (September 1900). "The Feeding of Parrots". Avicultural Magazine. VI (71): 240–5.

- Juniper, p. 30

- Bates, Busenbark (1978). Parrots and Related Birds. TFH Publications Inc. ISBN 0-87666-967-4.

- Vedantam, Shankar (24 December 2002). "A Rare Bird Flies Home For Good" (PDF). The Washington Post.

- Hurrell, Shaun (24 June 2016). "Spix's Macaw reappears in Brazil". BirdLife International Americas. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016.

- Juniper, pp. 55–80

- "Born to be Wild". Noah's Ark. 1997.

- "Gorgo". Mystery Science Theater 3000. 1998.

- director Carlos Saldanha (2011). Rio (motion picture). Brazil: Blue Sky Studios.

- director Carlos Saldanha (2014). Rio 2 (motion picture). Brazil: Blue Sky Studios.

- Law and Order SVU Episode "Wildlife". Original air date 18 November 2008

Cited texts

- Juniper, Tony (2002). Spix's Macaw: The Race to Save the World's Rarest Bird. NY, NY: Atria Books. ISBN 0-7434-7550-X.

- del Hoyo, et al.(eds) (1997) Handbook of the Birds of the World, vol.4, Family Psittacidae (Parrots), N.J. Collar, pp-280-479, Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain ISBN 84-87334-22-9

- Donald, Pain, Marsden & Collar (2010) Facing Extinction: the World's Rarest Birds and the Race to Save Them T. & A. D. Poyser ISBN 0-7136-7021-5

Further reading

A note on the references. There are only about a dozen original ornithological research papers devoted exclusively to the Spix written in the last 40 years. Most are collected at www.bluemacaws.org. A comprehensive natural and conservation history through late 2002 is available in Juniper's Spix Macaw book. More recent information is available in periodic reports about the parrots at Loro Parque and Al Wabra. Most other material is derived.

- Sick, Helmut (1993). Birds in Brazil: A Natural History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08569-2.

- Silva, Tony (1993). A Monograph of Macaws and Conures. ISBN 1-895270-00-6.

External links

- Macaw-facts.com: Spix Macaw research – in-depth articles.

- Bluemacaws.org: Blue Macaws website

- ARKive: Cyanopsitta spixii – photos, videos, information.

- Animal diversity web: Cyanopsitta spixii

- Birdlife International: Spix's macaw factsheet

- BBC Nature: Spix's macaw