Liturgical east and west

Liturgical east and west is a concept in the orientation of churches. It refers to the fact that the end of a church which has the altar, for symbolic religious reasons, is traditionally on the east side of the church (to the right in a diagram).

Traditionally churches are constructed so that during the celebration of the morning liturgy the priest and congregation face towards the rising sun, a symbol of Christ and the Second Coming.[1] However, frequently the building cannot be built to match liturgical direction. In parish churches, liturgical directions often do not coincide with geography; even in cathedrals, liturgical and geographic directions can be in almost precise opposition (for example, at St. Mark's Episcopal Cathedral, Seattle, liturgical east is nearly due west).

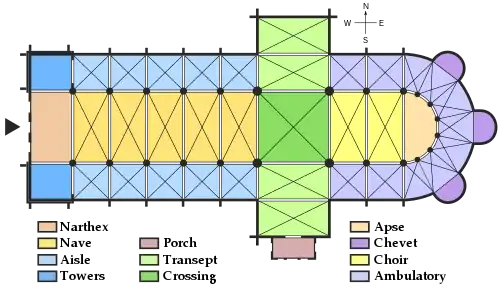

For convenience, churches are always described as though the end with the main altar is at the east, whatever the reality, with the other ends and sides described accordingly. Therefore common terms such as "east end", "west door", "north aisle" etc are immediately comprehensible. These orientations may be preceded by "liturgical", or not.[2] In a typical Western church, such as the one illustrated, the "back" of the church is therefore the west end, and as the visitor moves up the aisle towards the main altar the north side is to the left, and the south to the right.

A relatively unusual example of a church where the correct liturgical orientation was regarded as important, and overrode architectural considerations, is St Paul's, Covent Garden in London, of 1631, by Inigo Jones. This was the first completely new English church since the English Reformation, and given a site on the west side of the new Covent Garden development. Jones seems to have designed the church with three doors on the east end, leading down steps to the square, and under a grand classical temple portico; inside, the sanctuary and altar were at the opposite west end. However, it appears there were objections to this arrangement, and when the church opened the three doors onto the square were blocked off, and the entrance to the church was through the west end, with the sanctuary and altar at the "correct" east end.[3]

References

- "Facing East". Catholic Culture. October 1999. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- "East" in Curl, James Stephens, Encyclopaedia of Architectural Terms, 1993, Donhead Publishing, ISBN 1873394047, 9781873394045

- Summerson, John, Architecture in Britain, 1530-1830, pp. 125-126, 1991 (8th edn., revised), Penguin, Pelican history of art, ISBN 0140560033