Liudvika Didžiulienė

Liudvika Didžiulienė (1856–1925) also known by her pen name Žmona (wife) was a Lithuanian writer and activist during the Lithuanian National Revival. Having published her first story in 1892, she became the first Lithuanian woman writer.

Liudvika Didžiulienė | |

|---|---|

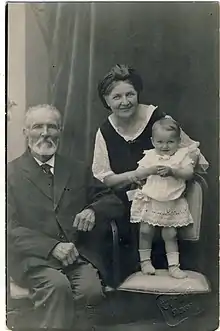

.jpeg.webp) Didžiulienė around 1896 | |

| Born | Liudvika Nitaitė 3 May 1856 Robliai, Russian Empire |

| Died | 25 October 1925 (aged 69) Griežionėlės, Lithuania |

| Nationality | Lithuanian |

| Other names | Žmona (pen name) |

| Occupation(s) | Writer, activist |

| Movement | Lithuanian National Revival |

| Spouse | Stanislovas Didžiulis |

Educated at home by her parents and tutors, Didžiulienė did not receive any formal education. Together with her husband Stanislovas Didžiulis, she supported the Lithuanian book smugglers and their home was frequently visited by various Lithuanian activists. She contributed her fiction and articles to various Lithuanian periodicals, collected examples of Lithuanian folklore, educated local residents. In 1896, Didžiulienė moved to Mitau (Jelgava) where she established a dormitory for Lithuanian students and organized Lithuanian cultural evenings, held literary readings and discussions, etc. for the Lithuanian community. When her husband and two sons were sentenced for the participation in the Russian Revolution of 1905, she returned to Lithuania. In 1915–1924, she lived with her daughter in Yalta and worked at a military hospital and tuberculosis sanatorium.

Due to her busy family and social life, Didžiulienė never had much time to write. She wrote short stories and plays for the amateur Lithuanian theater. Her works propagate the ideas of the Lithuanian National Revival and highlighting social inequality. They are often didactic and sentimental. During her years in Yalta, she wrote few works about the Crimean Tatars.

Biography

Early life

Didžiulienė (née Nitaitė) was born on 3 May 1856 into a Lithuanian family in Robliai in the present-day Rokiškis District Municipality. She grew up in Vaitkūnai near Salos and Rokiškis.[1] Her father worked as an administrator in a manor. She was educated at home by her parents and later by private tutors.[2] She learned five languages (in addition to native Lithuanian, she learned Polish, Russian, German, French, and Latvian) as well as to play a piano.[2] From an early age, despite the Lithuanian press ban, she was exposed to Lithuanian literature, including works by Motiejus Valančius and Antanas Baranauskas.[3] In her memoirs, Didžiulienė wrote that in 1875 she completed operetta Piršlės ir veselijos (Matchmaking and Weddings) based on Lithuanian folk songs, but the work has not survived.[1]

On 25 August 1877, she married Stanislovas Didžiulis, a descendant of an old Lithuanian noble family, who shared her interest in Lithuanian language and culture.[4] The newlyweds settled in Didžiulis' estate in Griežionėlės in the present-day Anykščiai District Municipality. The marriage was difficult as Didžiulis was stubborn even despotic and unfaithful.[5] However, they had a total of nine children – five daughters and three sons grew to adulthood while one son died in infancy.[1]

Activist

Didžiulienė was active in the local community in Griežionėlės – she taught local people reading and writing, basic hygiene, culinary, gardening. The family also helped Lithuanian book smugglers, including Jurgis Bielinis and Kazys Ūdra, to hide and distribute the banned Lithuanian publications.[6] Didžiulienė also wrote fiction and articles wis.th practical advice for Lithuanian periodicals Varpas and Ūkininkas.[7] Didžiulis collected Lithuanian books; the library eventually included about 1,000 titles.[8] In summer, their house was visited by various Lithuanian activists, including Antanas Baranauskas, Jonas Jablonskis, Motiejus Čepas, Mečislovas Davainis-Silvestraitis, Liudvikas Vaineikis.[9] In 1893, encouraged by Silvestras Baltramaitis who was impressed by her sausages, Didžiulienė published Lietuvos gaspadinė (Lithuanian Housewife), the first Lithuanian cookbook.[7] It was first published as a supplement to Ūkininkas and due to demand an expanded edition was published the same year. It was further republished in 1895, 1904, 1913, and 1927.[10] A new edition was published in 2018 and was in the top best-seller lists for at least six weeks in Lithuania.[11]

In 1896, Didžiulienė moved to Mitau (Jelgava) in the present-day Latvia so that her children could receive formal education.[7] There she established a dormitory for 12 to 14 Lithuanian students.[1] She not only rented rooms, but also taught proper manners and ensured students completed their schoolwork.[12] In fall 1896, several of her tenants, including Antanas Smetona, protested the requirement to pray in Russian at school.[13] The students were expelled and Didžiulienė was forced to downsize her dormitory – she could keep tenants only by claiming they were her relatives.[12] She obtained 500 rubles from Jonas Šliūpas for the expelled students and helped them find other schools. Eventually, she was able to reopen her dormitory.[12] During eleven years, her tenants included future President Antanas Smetona, Prime Minister Juozas Tūbelis,[14] writer Konstantinas Jasiukaitis, theater director Juozas Vaičkus, Minister of the Interior Vladas Požela, painter Justinas Vienožinskis, communist Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas (who later became her son-in-law).[15]

There was a community of Lithuanians in Mitau which centered around Jonas Jablonskis who worked as a teacher at the Mitau Gymnasium. However, in 1896, Jablonskis was reassigned to Revel (Tallinn). Didžiulienė filled in the void and organized Lithuanian cultural evenings, held literary readings and discussions, distributed illegal Lithuanian press, taught Lithuanian folk songs, encouraged others to write to Lithuanian periodicals.[16]

Family troubles

In 1906, her husband and two sons were arrested for participating in the Russian Revolution of 1905. Stanislovas Didžiulis and his son Antanas were deported to Siberia for life, though Antanas managed to escape and enroll into the Jagiellonian University in Kraków to study medicine. Another son Algirdas was deported for five years to Turukhansk.[15] Didžiulienė had to return from Mitau to the estate in Griežionėlės to take care of the farm. Her daughter Vanda married communist activist Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas and was also imprisoned and in hiding from the Tsarist police. Didžiulienė supported and helped her family.[15]

Despite the setbacks, she remained active in Lithuanian cultural life. She joined the Lithuanian Scientific Society, collected examples of Lithuanian folklore some of which was published in the journal Lietuvių tauta, wrote articles about poets Antanas Strazdas and Antanas Vienažindys, became friends with Jurgis Šlapelis and Marija Šlapelienė who owned a Lithuanian bookstore in Vilnius.[17] She also participated in the establishment of the Lithuanian Women's Association in June 1905, was a delate to the Great Seimas of Vilnius in December 1905, and attendee of the First Congress of Lithuanian Women in October 1907.[1]

In spring 1915, as World War I frontlines were approaching, Didžiulienė decided to visit her daughter Vanda who lived in Yalta. She brought her manuscripts with her, but they were stolen at a train station which was a severe blow to Didžiulienė who became sick for two months.[17] The visit was supposed to be temporary, but due to was lasted for nine years. Didžiulienė worked as a nurse in a military hospital and as an administrator of a Lithuanian sanatorium for tuberculosis patients.[17] After the February Revolution, she was joined by her ill and disabled husband who was released from his deportation.[17] Despite these responsibilities, she found time to write. She wrote the play Give me Freedom about women of the Crimean Tatars which was translated from Russian to Tatr and staged by a local theater.[18][19] She also published several articles in the local press using pen name Grazhdanka (Citizen).[1]

Death and legacy

Didžiulienė finally received travel permits and returned to Griežionėlės in August 1924. Her manuscripts were once again lost in transit. She was disappointed by her reception in independent Lithuania.[20] One of her last works was a satirical poem in Polish about youthful idealists who became greedy opportunists and bureaucrats.[20] Encouraged by Juozas Tumas-Vaižgantas, she wrote her valuable memoirs which though unfinished were published in 1926 already after her death.[21] Didžiulienė contracted pneumonia and died on 25 October 1925. She was buried on a hill in nearby Padvarninkai. Her tombstone was designed by Bernardas Bučas.[22]

After several petitions by Didžiulis' family, Soviet authorities established a memorial museum in Griežionėlės in 1968.[23] In 2007, the public library of the Anykščiai District Municipality was renamed after Stanislovas Didžiulis and his wife Didžiulienė.[1]

Works

Due to her busy family and social life, Didžiulienė never had an opportunity to devote substantial amount of time to writing. As such, she left only a handful of works.[14] At least two plays and several unfinished works were lost when her manuscripts disappeared during World War I.[1] Didžiulienė wrote short stories and plays which were published in various periodicals or remained unpublished. Only her comedy Lietuvaitės (Lithuanian Women) was published as a separate booklet in 1912.[14] Two volumes of her collected works and letters were published in 1996–1998.[1]

Considering education as the basis for the rebirth of the nation, Didižulienė sought to educate and enlighten her readers. Her works serve a clear purpose to propagate the ideas of the Lithuanian National Revival and are realist and often didactic.[1][19] During the Soviet era, her works were valued for highlighting social inequality.[10]

Her first short story Tėvynės sūnus (Son of the Homeland) was published in Varpas in 1892. It was the first Lithuanian work of fiction published by a woman.[14] The story deals with Juozas Baublys, a young Lithuanian doctor who works for the benefit of the Lithuanian people. However, he weds a daughter of Polonized nobles, becomes ashamed of his low birth, and ceases his work for the public good.[24] Similar theme of temptations faced by young activists is explored in the short story Dėl tėvynės! (For the Homeland!). It explores lives of five friends who upon graduation promise to be active in public life, but only the poorest one keeps his word.[24] In Didžiulienės' works, many women, particularly those that are uneducated or of foreign birth, are depicted negatively as a force corrupting ideals of young Lithuanian men. Such women are greedy, selfish, caring only about domestic life and money. The most vivid of such characters is Uršulė Bitautienė from the short story Ne pagal Jurgio kepurė[24] (first published in 1996).[1]

Her longest and one of the most important stories is Atgajėlė (written around 1895, first published in 1904) which tells the sentimental love story of Amelija, daughter of poor Polonized nobles, who rejects advances of a vainglorious noble and marries Jonas, an educated son of a local farmer.[24] In her later works, Didžiulienė explored the topic of harsh, unhappy childhood. Stories such as Juzuko vargai (Plight of Juzukas), Našlaičių eglutė (Orphans' Christmas Tree), Tremtinių vaikai (Children of the Deportees) are sincere, compassionate, attuned to children's psychology.[24] During the years spent in Yalta, Didžiulienė wrote several stories about the Crimean Tatars in which she explored not only material culture but also spiritual life of the Tatars.[19]

Didžiulienė wrote several plays, including comedies Lietuvaitės (Lithuanian Women) and Paskubėjo (Hastened) and dramas Katei juokai – pelei verksmai (Cat Laughs – Mouse Cries) and Vakaruškos (Parties).[19] They were likely written in Mitau for the Lithuanian amateur theater and as such feature vivid characters, dynamic dialogue, clear conflicts. Many of the plays are overly sentimental. Most dramas feature unrequited love while comedies center on courtship misunderstandings.[19] Her most popular play Lietuvaitės makes fun of efforts by two vain daughters of Polonized nobles to appear more Lithuanian so that they could entice two Lithuanian students into marriage. The plan works, but the father intervenes and marries his daughters off to sons of other Polonized nobles.[19]

References

- Anykštėnų biografijų žinynas 2022.

- Butkuvienė 2007, p. 243.

- Butkuvienė 2007, p. 244.

- Butkuvienė 2007, pp. 244–245.

- Butkuvienė 2007, p. 245.

- Butkuvienė 2007, p. 246.

- Butkuvienė 2007, p. 247.

- Lietuvninkaitė 2004, p. 20.

- Butkuvienė 2007, pp. 245–246.

- Berezauskienė 2021.

- Šilelis 2019.

- Butkuvienė 2007, p. 248.

- Krikštaponis 2011.

- Daugnora 2001, p. 543.

- Butkuvienė 2007, p. 249.

- Butkuvienė 2007, pp. 247–248.

- Butkuvienė 2007, p. 250.

- Butkuvienė 2007, pp. 250–251.

- Daugnora 2001, p. 545.

- Butkuvienė 2007, p. 251.

- Daugnora 2001, pp. 543, 545.

- Butkuvienė 2007, pp. 251–252.

- Lietuvninkaitė 2004, p. 27.

- Daugnora 2001, p. 544.

Bibliography

- Anykštėnų biografijų žinynas (5 April 2022). "Liudvika Didžiulienė" (in Lithuanian). Pasaulio anykštėnų bendrija. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- Berezauskienė, Audronė (11 July 2021). "Pirmosios lietuviškos kulinarijos knygos autorei – 165-eri". Nyksciai.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- Butkuvienė, Anelė (2007). Garsios Lietuvos moterys (in Lithuanian). Baltos lankos. ISBN 978-9955-23-065-6.

- Daugnora, Eligijus (2001). "Iš didaktinės prozos į meninę". In Girdzijauskas, Juozas (ed.). Lietuvių literatūros istorija: XIX amžius (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos institutas. ISBN 9986513693.

- Krikštaponis, Vilmantas (11 May 2011). "Lietuvių tautos žadintoja: Liudvikos Didžiulienės-Žmonos 155-osioms gimimo metinėms". XXI amžius (in Lithuanian). 35 (1915). ISSN 2029-1299.

- Lietuvninkaitė, Nijolė (2004). Stanislovo Didžiulio asmeninė biblioteka: katalogas (in Lithuanian). Kaunas: Technologija. ISBN 9955-09-790-6.

- Šilelis (22 March 2019). "Kulinarija – aukštumoje". Nyksciai.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 28 August 2022.