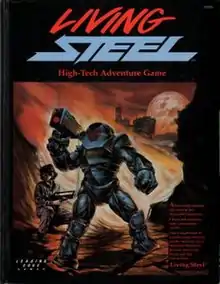

Living Steel

Living Steel is a high-tech science fiction role-playing game published by Leading Edge Games in 1987.

| |

| Designers | Barry Nakazono |

|---|---|

| Publishers | Leading Edge Games |

| Publication | 1987 |

| Genres | Science fiction |

| Systems | Phoenix Command |

Setting

In 2349, the human-colonized planet Rhand has just suffered a devastating attack by an alien race called the Spectrals. In addition to bombardment from space, the Spectrals released a virus onto the planet which turned most of the population into dangerous sociopaths. The Spectral warship then crashed into the planet's surface, causing further widespread destruction. In the aftermath, survivors are competing viciously with each other and the remaining Spectrals for the essentials of life.[1]

Players take on the role of Ringers, elite soldiers who were in cyrogenic sleep until this emergency. The Ringers must secure a base, make contact with the surrounding population and begin the work of rebuilding, reeducation, and defense against further Spectral attacks.[1]

Gameplay

Character generation

Each player rolls four dice and adds the sum to 48. These points are then allocated to Strength, Intelligence, Will, Health and Agility. Further dice rolls on background tables develops the character's starting experience. Skills are then chosen, and each character receives basic equipment.[1]

Combat

Combat is broken down into 2-second segments. Players choose which combat actions to assign to movement and firing. If the target is hit, further die rolls indicate the location of the hit and how much damage was done.[1]

Publication history

Designer Barry Nakazono originally titled this role-playing game Rhand, but then retitled it Living Steel.[2] He used a simplified version of Leading Edge's Phoenix Command game system for the game. The rules were presented first as a boxed set in 1987 with illustrations and graphic design by Jon Conrad, Toni Dennis, Steve Huston, Scott Miller, and Maggie Parrand.[3] The product was republished in a single hardbound book in 1988.

In 1994, Leading Edge released a set of 25 mm metal miniatures that could be used with the game. The company went out of business shortly afterwards.[2]

Reception

In Issue 33 of Challenge, Julia Martin found the game "marvelous to look at. Graphically, it is a very attractive game." But he noted that although, in theory, the entire universe seemed to be available for play, most of the material in this set referred to the planet of Rhand, with no clear means of leaving the planet's surface. As Martin noted, "The potential for 'high adventure' which the company claims is certainly there, but it may be hard for referees to achieve for their players with the materials presented in the game set alone." During character creation, Martin noted the problem with the character class known as Ringer, which has the ability to use high technology equipment such as Power Armor. But that equipment needs to be recharged daily, and in the post-apocalyptic setting of Rhand, there is little power to be obtained. Martin noted, "The result is that most Ringers which players will create will be played infrequently at best — a frustrating situation since these are the most detailed, motivated and best equipped characters one can generate." Martin also did not like combat, saying, "although the combat system is realistic, the methods used to achieve this realism lead to it being very complex. Every combat involves consulting a minimum of eight tables. A combat which takes seconds or minutes in game time can take a half hour or more in real time quite easily." He also found combat to be "incredibly deadly. The average character can easily die in his or her first combat from only one realistic wound. [...] This much realism can easily lead to bored and frustrated players." In terms of adventures, Martin warned potential gamemasters that "ideas for adventures are not presented in detail and rely mainly on rather complicated Mission Generation tables, a sort of random scenario generator system for the bare bones of an adventure. [...] Considerable referee originality and thought will have to be put into creation of adventures." Martin concluded, "Those who really enjoy realistic combat and do not mind complexity and a slower combat sequence in pursuit of it will truly enjoy Living Steel. [...] Overall, Living Steel has a fascinating historical setting, wonderful equipment, detailed character creation, problematic game systems, and little support for the referee."[3]

In the inaugural issue of Games International, Jake Thornton found the movement and combat rules complex, but admitted that "Once you have the hang of it, the movement rules work very nicely [and] blazing away at someone is easy to work out." However, Thornton pointed out an apparent dichotomy: although "a large portion of the goodies in the box are to do with combat", the rulebook states "Living Steel should not be a game of military conquest". Despite this, he concluded by giving the game an above-average rating of 4 out of 5, saying, "All in all, Living Steel impressed me."[1]

Other reviews and commentary

- White Wolf #9 (1988)

- Arcane #16 (February 1997)

- Casus Belli #42 (Dec 1987)[4]

- The Complete Guide to Role-Playing Games[5]

References

- Thornton, Jake (October 1988). "Role Games". Games International. No. 1. pp. 39–40.

- "Living Steel". miniatures-workshop.com. Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- Martin, Julia (1988). "Reviews". Challenge. No. 33. pp. 62–63.

- "Têtes d'Affiches | Article | RPGGeek".

- https://archive.org/details/completeguidetor0000swan/page/118/mode/2up