Loch Maree Hotel botulism poisoning

The Loch Maree Hotel botulism poisoning of 1922 was the first recorded outbreak of botulism in the United Kingdom. Eight people died, with the resulting public inquiry linking all the deaths to the hotel's potted duck paste.

Loch Maree Hotel, The Graphic (1877)[1] | |

| Date | 15–21 August 1922 |

|---|---|

| Location | Loch Maree, Northwest Highlands of Scotland |

| Coordinates | 57°40′31″N 05°29′55″W |

| Also known as | The Loch Maree tragedy |

| Cause | Botulism from potted duck-paste |

| Deaths | 8 |

Loch Maree was a popular location for holiday makers, sports fishermen and romantic breaks, and interest in the event was heightened by the hotel's scenic location.

Background

Multiple deaths caused by botulism had occurred in 1920 in the United States when the origin was found to be glassed olives.[2] Previously, there had been an outbreak associated with sausages from Württemberg in Germany.[3]

Chronology

14 August 1922

On 14 August 1922, a group of 13 sports fishermen, two of their wives, 17 gillies and three mountain climbers were present at the Loch Maree Hotel on the edge of Loch Maree in the Scottish Highlands. Totalling 35, they took packed lunches prepared by the hotel staff.[4]

Forty-eight people dined at the hotel that evening,[4] and the gillies returned home to their cottages.[4] There were no complaints of illness that evening.[4]

15 August 1922

At 3 am, John Stewart, aged 70, who had been visiting the hotel regularly for the previous 40 years, was the first guest to fall ill with vomiting and drooped eyelids.[5] Alex Robertson, the owner, called Dr Knox,[5] the local physician. But by the time he came later in the morning, several others had become ill, and he in turn called upon T. K. Monro, Regius Professor of Medicine and Therapeutics at Glasgow University, who happened to be nearby. However, by the time Monro arrived, 9 pm that day, the first death had occurred. The doctors then went to visit a gillie who had become ill; and after returning to the hotel, witnessed the second fatality.[4]

16 August 1922

By midday on 16 August 1922, there was a third death and a second gillie had also fallen sick. A number of physicians, many of whom were holidaying in and around the hotel, were also now involved. Baffled by the unusual presentations and the sudden deaths, they suspected food poisoning.[4] The public prosecutor was now informed, and the incident became a legal case and crime scene; primary suspect was the hotel's owner until Monro suggested food-borne disease.[4]

Investigation

The attending physicians had suspected food poisoning early in the week and began inquiries.[6] Medical officer of health William MacLean reported to the public prosecutor that "the symptoms and course of the disease are identical in essentials with those described by Van Ermengem as his ‘second type’ in his investigations of sausage poisoning in the eighteen-nineties".[4]

A second inquiry also began in the first week, on behalf of the Scottish health board by Dr Dittmer. This was to prevent further occurrences and to allay public fear.[4]

All eight victims were the only members of the group to have eaten duck paste sandwiches. The duck paste was home-canned by hotel staff.[4]

A detailed assessment was made of the making up of sandwiches, including how many sandwiches were placed in each packed lunch. Two glass pots of meat were used, each providing for nine or 12 sandwiches, or a total of 18 or 24. Twenty lots of sandwiches were made that day using the contents of two containers of potted wild duck paste and ham and tongue. Other sandwiches were also made, from ingredients including beef, ham, jam and eggs.[4]

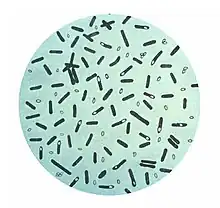

Investigators obtained the little that remained of the left-over food from the hotel rubbish. Botulinum toxin was found, and samples were sent to the distinguished microbiologist Bruce White. The most significant sample was from one of the ill gillie's leftover potted duck sandwich, which was buried in a garden by a colleague to avoid the hens eating it. Wrapped in paper, it was recovered during the night of the 17 August, fully intact.[4]

The origins of the potted meat were traced. Four jars of the meat were purchased from Lazenby's of London in June 1922 and included "chicken, ham, and turkey, all mixed with tongue; and wild duck".[5] The Lazenby production plant was scrutinised too, but all was found to be in good working order.[5]

The public enquiry was held in March 1922, with intense publicity. At one time, one tabloid named the hotel "The Hotel of Death".[5]

Witness accounts

The future air marshal Sir Thomas Elmhirst described how, as a young guest at the hotel, he narrowly avoided being poisoned when he joined his brother and parents there for a week of fishing. Arriving late, they were given ham sandwiches rather than potted meat, which had run out, and thus were saved. Elmhirst recorded how a judge in the room next to him suffered a painful death while a major and his wife, who were guests, gave their sandwich to their gillie as they never ate potted meat. The gillie later died.[7]

Reaction and legacy

As the first recorded outbreak of botulism in the United Kingdom,[8] the incident resulted in extraordinary publicity.[4][9] The area was a popular location for holiday makers, sports fishermen and romantic breaks and the poisoning occurred in the height of the holiday season. The hotel's scenic location made the unusual interest in the tragedy even more extensive.[4]

The incident ultimately led to anti-toxins being made more easily available and packaging of preserved food was changed to allow easier identification of its origin.[5] However, botulism did not become a notifiable disease in the UK until 1949.[8] The events at Loch Maree are now used as a case study in the detection of food poisoning.[4] Similar outbreaks are considered rare, with 17 incidents reported in the UK between 1922 and 2011, including a large outbreak in 1989 connected to hazelnut yoghurt and an episode in 2011 with a suspected link to a korma sauce.[10]

References

- "Loch Maree Hotel", The Graphic, Vol. XVI, No. 410, 6 October 1877.

- Horowitz, B. Zane (1 April 2011). "The ripe olive scare and hotel Loch Maree tragedy: Botulism under glass in the 1920s". Clinical Toxicology. 49 (4): 345–347. doi:10.3109/15563650.2011.571694. PMID 21563914. S2CID 207562569.

- "Botulism and Food Preservation (The Loch Maree Tragedy)". Nature. 111 (2796): 737. 1 June 1923. Bibcode:1923Natur.111S.737.. doi:10.1038/111737c0. hdl:2027/uc1.b3136163. S2CID 4103609.

- Pawsey, Rosa K. (2002). "2. Expectations of Food Control Systems – in the Past, and Now". Case Studies in Food Microbiology for Food Safety and Quality. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 26–35. ISBN 978-0-85404-626-3.

- McThenia, Tal (15 November 2018). "The Lethal Lunch That Shook Scotland". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- "Poison in Food. Ross-shire Visitors' Fate. Six People Succumb". The Glasgow Herald. 18 August 1922. p. 7. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- Fullarton, Donald (2014). "Second account of loch tragedy". www.helensburgh-heritage.co.uk. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- Berger, Stephen. (2018). "United Kingdom". Botulism: Global Status. Los Angeles: Gideon Informatics Inc. p. 94. ISBN 9781498819510.

- Monro, T. K.; Knox, William W. N. (17 February 1923). "Remarks on Botulism as seen in Scotland in 1922". British Medical Journal. 1 (3242): 279–281. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.3242.279. ISSN 0007-1447. PMC 2316130.

- Browning, L M; Prempeh, H; Little, C; Houston, C; Grant, K; Cowden, J M; on behalf of the United Kingdom Bot, Collective (8 December 2011). "An outbreak of food-borne botulism in Scotland, United Kingdom, November 2011". Eurosurveillance. 16 (49): 20036. doi:10.2807/ese.16.49.20036-en. ISSN 1560-7917. PMID 22172331.