Hart Merriam Schultz

Hart Merriam Schultz, also known by his Blackfoot name, Lone Wolf (Nitoh Mahkwii or Ni-tah-mah-kwi-i), was an Indian artist of the twentieth century. Most of his work was done in either Arizona or Montana, after he completed his artistic studies in Los Angeles and Chicago. He would spend his summers in a tipi studio in Montana, and his winters in Arizona, either in Tucson, or at the studio his father created for him at Butterfly Lodge, near Eagar.

Hart Merriam Schultz | |

|---|---|

| Nitoh Mahkwii or Ni-tah-mah-kwi-i | |

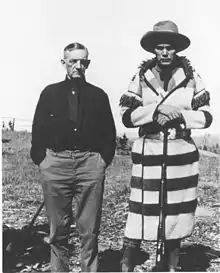

Hart Merriam Schultz, a.k.a. Lone Wolf, with his father, James Willard Schultz, ca. 1920 | |

| Born | February 18, 1882 Blackfoot Reservation, Montana |

| Died | February 9, 1970 (aged 87) |

| Nationality | American |

| Style | Indian, western |

Early life

Lone Wolf was the only son of noted explorer, author, and guide, James Willard Schultz, and his Blackfoot wife, Natahki (meaning "Fine Shield Woman") near Birch Creek on the Blackfoot Reservation in Montana on February 18, 1882.[1][2][3]: 156 His mother was a survivor of the Baker massacre in 1870.[4] He was born while his father was away on a trading trip to Carroll, Montana, and while it was the prerogative of the father to name a child in the Blackfoot culture, his mother's uncle, Red Eagle, named him Nitoh Mahkwii in the father's absence. However, upon his return the elder Schultz renamed the child Hart Merriam, after his good friend, Clinton Hart Merriam.

Lone Wolf grew up preferring his Indian name, continuing to use it throughout his life. His early years were spent on his parents' ranch in Montana on the Two Medicine River.[3]: 157 With his father's frequent absences as a guide through Glacier National Park, it fell to Lone Wolf and his uncle, Last Rider, to run the family ranch.[5]

His maternal grandfather, Yellow Wolf, taught him the rudiments of how to use natural colors and how to draw animals and people.[4] And he sold his first work to a clerk who worked at Kipp's Trading Post in nearby Browning.[5] He disliked the schools he was sent to, first at nearby Fort Shaw, then at a Catholic school. When he and a classmate beat up a priest who was attempting to enforce corporal punishment on Lone Wolf, he was expelled, and returned home to the ranch, after which his parents decided to temporarily forgo a formal education.[3]: 157 While living on his parents' ranch he learned the skills necessary to work as a cowboy and ranch hand. With his mother's death in 1903 he left the ranch and traveled south, finally ending up near the Grand Canyon, where he worked as a cowboy, wrangler, and guide, as well as continuing to practice his art.[6] While at the Canyon, he met Thomas Moran, who encouraged the young man to pursue his art.[5] In 1909 he went to Los Angeles, where he began working in the fledgling film industry, appearing in the one-reelers of James Young Deer. Young Deer was the first American Indian filmmaker and producer in Hollywood, making films for Pathe Films.[7] While in Los Angeles, he was reunited with his father, who had remarried in 1907. He lived with his father and step-mother while in Los Angeles.[8] After his brief stint in film, due to the influence of Thomas Moran, he studied art at the Los Angeles Artist Student League. Following that, he continued his art studies in Chicago at the Chicago Art Institute in 1914–15.[6][9] After leaving Chicago, he returned to Montana, where he worked on the Galbaith Ranch. While there, In 1916, he met the daughter of the ranch's foreman, Naoma Tracy (also known as Naomi). He courted her for a single day before taking her by horseback to Cut Bank, where they were married by a justice of the peace. The two remained married until his death in 1970.[6][5]

Career

Lone Wolf was one of the first Indian artists to paint other Indians, and Indian subjects. He was also one of the first Indian artists to be academically trained in art. He was known for both his painting and sculpting skills.[2] He played a "significant role" in capturing the events of the American West during the latter part of the 1800s and the early part of the 1900s. He had personal experience, as well as his tribe's personal knowledge of people and events.[10] He was the first Indian to achieve national recognition as an artist, creating over 500 paintings. He was influenced and encouraged by Thomas Moran, who he met during his time wrangling at the Grand Canyon, and his style has been compared to that of Frederic Remington and Charles Marion Russell.[9][11] Russell also encouraged and instructed Lone Wolf in his early career.[12] Lone Wolf had his first solo show in Los Angeles in 1917. The headline in the Los Angeles Times about the exhibition read, "Vance Thompson Discovers Wonderful Indian Artist, An Artist With a Vision."[5] In that article, Vance Thompson said of Lone Wolf, "The message he has to give is his own; and already he has shaped – if he has not perfected – a distinct, individual and interesting technique."[13] He went to say, "It is a rare thing to discover an artist. I have seen the young painters pass in droves through the schools and salons of Paris, and in 20 years I can claim to have been the discoverer of only one great artist. Now I like to think that I have, at last, discovered another and he is an artist who has authentic vision, sincerity and a brush which is already capable of doing precisely the thing he wants it to..."[5]

In 1918 his father authored Bird Woman, a novel about Sacajawea, and dedicated the book to Lone Wolf, who provided the illustrations for the novel.[14] Schultz said in his dedication:

"I dedicate this book to my son, Hart Merriam Schultz, or Ni-tah'-mah-kwi-i (Lone Wolf), as his mother's people name him. Born near the close of the buffalo days he was, and ever since with his baby hands he began to model statuettes of horses and buffalo and deer with clay from the river-banks, his one object in life has been to make a name for himself in the world of art. And now, at last, he has furnished the drawings for one of my books, this book. His own grandfather, Black Eagle, was a mighty warrior against the Snakes. What would the old man say, I wonder, if he were alive and could see his grandson so sympathetically picturing incidents in the life of Bird Woman, a daughter of the Snakes."[6][9][15]

He split his time between Arizona and Montana. His father had built a hunting lodge near Eagar, Arizona, named Butterfly Lodge (Apuni Oyis in the Blackfoot language), and he gave it to Lone Wolf and his wife in 1920. He added an artist's studio to the cabin during the 1920s. He would spend the winter, spring, and fall at Butterfly Lodge, while the summers he would spend in Montana, in a studio inside a tipi. Some time was also spent during the winters in Tucson, when Lone Wolf would occasionally participate in the La Fiesta de los Vaqueros festival by dressing in traditional Blackfoot regalia and riding horseback in the parade.[6][16]

His career as an artist began by painting pictures for the Santa Fe Railroad, which he sold to them for $100 each.[11] Lone Wolf created a large five foot by eight foot portrait of the LDS pioneer Jacob Hamblin. He donated the painting to the local LDS community in Eagar, where it is still on display.[6] He would play up his Indian background, wearing full Blackfoot outfits to his gallery and museum openings.[11] He achieved national acclaim with his first one-man show in Los Angeles in 1917. During the 1920s he became a successful professional artist of paintings and sculptures based on his Blackfoot heritage and experiences. His visit to New York City during this period garnered the headline in the Evening Telegram: "A Real Indian Painter Paints Indian Life."[7] An article in Current Opinion stated that he was the only Indian painter in the United States, whose work had a "unique appeal" and said, "...his work portrays phases of life that until now have not found an interpreter."[13] The photojournalist, William van der Weyde said that Lone Wolf was "young, courageous and loves both his art and his race."[17] The success of his exhibition in New York in 1922 was considered a major breakthrough for Indian artists in America.[12] As time went on, he earned more and more for his paintings, eventually earning thousands of dollars for them. He would sell his art to European royalty; to presidents Herbert Hoover, Theodore Roosevelt, and Calvin Coolidge; and to other notable people such as Buffalo Bill Cody and Charles Russell.[11][7]

His art remains part of the permanent collections of several museums, including the Tucson Museum of Art.[10]

Later life and death

In 1956, he gave an interview which was captured on tape, wherein he discussed his growing up in Montana, and learning to paint at the hands of the elders of his mother's tribe.[18] He actively continued painting through the early 1960s. He is still considered one of the most important artists of Glacier National Park. His body of work helps to understand "the significant contributions by marginalized artists who successfully negotiated the terrain of the mainstream art world."[19] Lone Wolf died in St. Mary's hospital in Tucson, Arizona, on February 9, 1970. He was cremated, and his ashes were interred near the grave of his maternal uncle Last Rider in Montana.[6] He was buried on June 19, 1970, in an Indian ceremony which included four willow wands topped by eagle feathers placed at the corners of his grave. Paul Dyke, his adopted son, lowered the urn into the earth, and Lone Wolf's widow, Naomi, cast the first spade of earth into the grave. Afterwards, Naomi gave the eagle feathers to friends as remembrances. At some point during the next year, Naomi, despondent over Lone Wolf's death, committed suicide, using Lone Wolf's old revolver.[20] Two years after his death, his story was highlighted, along with pictures of his paintings and sculptures, in the first issue of the 1972 edition of Montana The Magazine of Western History. The article was written by Paul Dyke.[21]

References

- "The Artist". Butterfly Lodge Museum. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- "Biography: Lone Wolf". Ask Art. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- Glacier Association (2009). Stars Over Montana: A Centennial Celebration Of The Men Who Shaped Glacier National Park. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4617-4682-9.

- "Indian Artist Selects Reservation". Great Falls Tribune. June 14, 1970. p. 54. Retrieved July 26, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Call of the Mountain: The Artists of Glacier National Park". Hockaday Museum. October 12, 2002. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- "The Lodge". Butterfly Lodge Museum. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- "Lone Wolf (Hart M. Schultz): Cowboy, Actor & Artist Exhibition at Scottsdale's Museum of the West through August 31". Sonoran News. June 29, 2016. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- "Indians of North America". American Indian Culture and Research Journal. Los Angeles, California: American Indian Culture and Research Center, University of California: 157. 1986. ISSN 0161-6463.

- "Hart Merriam Schultz". Meadowlark Gallery. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- "Lone Wolf Premiere Retrospective to Open in Scottsdale". Arizona RedBook. June 8, 2016. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- Alshire, Noah. "Greer's Butterfly Lodge Museum". Arizona Scenic Roads. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- Holm, Tom (2009). The Great Confusion in Indian Affairs: Native Americans and Whites in the Progressive Era. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-77957-0.

- "Arizona Indian Painter Popular in New York City". The Coconino Sun. March 10, 1922. p. 8. Retrieved February 1, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "An Indian Heroine". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 27, 1918. p. 43. Retrieved February 1, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Schultz, James William (1918). Bird Woman (Sacajawea). New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Bird Woman (Sacajawea).

- Kay LaRae Read (June 17, 1992). "NHL Nomination: Butterfly Lodge (including accompanying 1 photo)". National Park Service.

- Wheeler, Edward Jewitt; Crane, Frank (1922). "The Only Indian Painter in America". Current Opinion. 72: 104.

- "Oral history interview, 1956". WorldCat. OCLC 35627050.

- Loscher, Tricia (2016). Lone Wolf (Hart M. Schultz): Cowboy, Actor and Artist (PhD thesis). University of Arizona. hdl:10150/621717.

- Scriver, Mary Strachan (2007). Bronze Inside and Out: A Biographical Memoir of Bob Scriver. Calgary, Alberta: University of Calgary Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-55238-227-1.

- "Montana Historical Society Highlights Lone Wolf Art". The Independent-Record. January 16, 1972. p. 18. Retrieved July 26, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.