Longfin mako shark

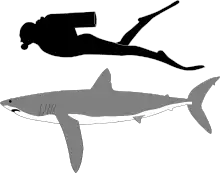

The longfin mako shark (Isurus paucus) is a species of mackerel shark in the family Lamnidae, with a probable worldwide distribution in temperate and tropical waters. An uncommon species, it is typically lumped together under the name "mako" with its better-known relative, the shortfin mako shark (I. oxyrinchus). The longfin mako is a pelagic species found in moderately deep water, having been reported to a depth of 220 m (720 ft). Growing to a maximum length of 4.3 m (14 ft), the slimmer build and long, broad pectoral fins of this shark suggest that it is a slower and less active swimmer than the shortfin mako.

| Longfin mako shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Lamniformes |

| Family: | Lamnidae |

| Genus: | Isurus |

| Species: | I. paucus |

| Binomial name | |

| Isurus paucus Guitart-Manday, 1966 | |

| |

| Range of the longfin mako shark | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Isurus alatus Garrick, 1967 Lamiostoma belyaevi Glückman, 1964 Isurus oxyrinchus (non Rafinesque, 1810) misapplied | |

Longfin mako sharks are predators that feed on small schooling bony fishes and cephalopods. Whether this shark is capable of elevating its body temperature above that of the surrounding water like the other members of its family is uncertain, though it possesses the requisite physiological adaptations. Reproduction in this species is aplacental viviparous, meaning the embryos hatch from eggs inside the uterus. In the later stages of development, the unborn young are fed nonviable eggs by the mother (oophagy). The litter size is typically two, but may be as many as eight. The longfin mako is of limited commercial value, as its meat and fins are of lower quality than those of other pelagic sharks; however, it is caught unintentionally in low numbers across its range. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed this species as endangered due to its rarity, low reproductive rate, and continuing bycatch mortality. In 2019, alongside the shortfin mako, the IUCN listed the longfin mako as "Endangered".[3][4][5]

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The original description of the longfin mako was published in 1966 by Cuban marine scientist Darío Guitart-Manday, in the scientific journal Poeyana, based on three adult specimens from the Caribbean Sea. An earlier synonym of this species may be Lamiostoma belyaevi, described by Glückman in 1964. However, the type specimen designated by Glückman consists of a set of fossil teeth that could not be confirmed as belonging to the longfin mako, thus the name paucus took precedence over belyaevi, despite being published later.[6] The specific epithet paucus is Latin for "few", referring to the rarity of this species relative to the shortfin mako.[7]

The sister species relationship between the longfin and shortfin mako has been confirmed by several phylogenetic studies based on mitochondrial DNA. In turn, the closest relative of the two mako sharks is the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias).[8] Fossil teeth belonging to the longfin mako have been recovered from the Muddy Creek marl of the Grange Burn formation, south of Hamilton, Australia, and from Mizumani Group in Gifu Prefecture, Japan. Both deposits date to the Middle Miocene Epoch (15–11 million years ago (mya)).[9][10] The oligo-miocene fossil shark tooth taxon Isurus retroflexus may be the ancestor to or even conspecific with the Longfin Mako.

Distribution and habitat

Widely scattered records suggest that the longfin mako shark has a worldwide distribution in tropical and warm-temperate oceans; the extent of its range is difficult to determine due to confusion with the shortfin mako. In the Atlantic Ocean, it is known from the Gulf Stream off the East Coast of the United States, the Caribbean, and southern Brazil in the west, and from the Iberian Peninsula to Ghana in the east, possibly including the Mediterranean Sea and Cape Verde. In the Indian Ocean, it has been reported from the Mozambique Channel. In the Pacific Ocean, it occurs off Japan and Taiwan, northeastern Australia, a number of islands in the Central Pacific northeast of Micronesia, and southern California.[6]

An inhabitant of the open ocean, the longfin mako generally remains in the upper mesopelagic zone during the day and ascends into the epipelagic zone at night. Off Cuba, it is most frequently caught at a depth of 110–220 m (360–720 ft) and is rare at depths above 90 m (300 ft). Off New South Wales, most catches occur at a depth of 50–190 m (160–620 ft), in areas with a surface temperature around 20–24 °C (68–75 °F).[11]

Description

The longfin mako is the larger of the two mako and the second-largest species in its family (after the great white), reaching upwards of 2.5 m (8.2 ft) in length and weighing over 70 kg (150 lb); females grow larger than males.[12] The largest reported longfin mako was a 4.3-metre-long (14 ft) female caught off Pompano Beach, Florida, in February 1984.[11] Large specimens can scale over 200 kg (440 lb) and can scale up to around 500 kg (1,100 lb).[13][14] This species has a slim, fusiform shape with a long, pointed snout and large eyes that lack nictitating membranes (protective third eyelids). Twelve to 13 tooth rows occur on either side of the upper jaw and 11–13 tooth rows are on either side of the lower jaw. The teeth are large and knife-shaped, without serrations or secondary cusps; the outermost teeth in the lower jaw protrude prominently from the mouth. The gill slits are long and extend onto the top of head.[6][12]

The pectoral fins are as long or longer than the head, with a nearly straight front margin and broad tips. The first dorsal fin is large with a rounded apex, and is placed behind the pectoral fins. The second dorsal and anal fins are tiny. The caudal peduncle is expanded laterally into strong keels. The caudal fin is crescent-shaped, with a small notch near the tip of the upper lobe. The dermal denticles are elliptical, longer than wide, with three to seven horizontal ridges leading to a toothed posterior margin. The coloration is dark blue to grayish black above and white below. The unpaired fins are dark except for a white rear margin on the anal fin; the pectoral and pelvic fins are dark above and white below with sharp gray posterior margins. In adults and large juveniles, the area beneath the snout, around the jaw, and the origin of the pectoral fins have dusky mottling.[6][12]

The most distinctive features of the longfin mako shark are its large pectoral fins

The most distinctive features of the longfin mako shark are its large pectoral fins Jaws

Jaws Lower teeth

Lower teeth Upper central teeth

Upper central teeth Upper teeth

Upper teeth

Biology and ecology

The biology of the longfin mako is little-known; it is somewhat common in the western Atlantic and possibly the central Pacific, while in the eastern Atlantic, it is rare and outnumbered over 1,000-fold by the shortfin mako in fishery landings.[1][6] The longfin mako's slender body and long, broad pectoral fins evoke the oceanic whitetip shark (Carcharhinus longimanus) and the blue shark (Prionace glauca), both slow-cruising sharks of upper oceanic waters. This morphological similarity suggests that the longfin mako is less active than the shortfin mako, one of the fastest and most energetic sharks.[6] Like the other members of its family, this species possesses blood vessel countercurrent exchange systems called the rete mirabilia (Latin for "wonderful net", singular rete mirabile) in its trunk musculature and around its eyes and brain. This system enables other mackerel sharks to conserve metabolic heat and maintain a higher body temperature than their environments, though whether the longfin mako is capable of the same is uncertain.[6]

The longfin mako has large eyes and is attracted to cyalume sticks (chemical lights), implying that it is a visual hunter. Its diet consists mainly of small, schooling bony fishes and squids. In October 1972, a 3.4-metre-long (11 ft) female with the broken bill from a swordfish (Xiphias gladias) lodged in her abdomen was caught in the northeastern Indian Ocean; whether the shark was preying on swordfish as the shortfin mako does, or encountered the swordfish in some other aggressive context is not known.[6][11] Adult longfin mako have no natural predators except for killer whales, while young individuals may fall prey to larger sharks.[12]

As in other mackerel sharks, the longfin mako is aplacental viviparous and typically gives birth to two pups at a time (one inside each uterus), though a 3.3-metre-long (11 ft) female pregnant with eight well-developed embryos was caught in the Mona Passage near Puerto Rico in January 1983.[11] The developing embryos are oophagous; once they deplete their supply of yolk, they sustain themselves by consuming large quantities of nonviable eggs ovulated by their mother. No evidence of sibling cannibalism is seen, as in the sand tiger shark (Carcharias taurus). The pups measure 97–120 cm (3.18–3.94 ft) long at birth, relatively larger than the young of the shortfin mako, and have proportionally longer heads and pectoral fins than the adults.[12][15] Capture records off Florida suggest that during the winter, females swim into shallow coastal waters to give birth.[16] Male and female sharks reach sexual maturity at lengths around 2 m (6.6 ft) and 2.5 m (8.2 ft), respectively.[11]

Human interactions

No attacks on humans have been attributed to the longfin mako shark.[6] Nevertheless, its large size and teeth make it potentially dangerous.[7] This shark is caught, generally in low numbers, as bycatch on longlines intended for tuna, swordfish, and other pelagic sharks, as well as in anchored gillnets and on hook-and-line. The meat is marketed fresh, frozen, or dried and salted, though it is considered to be of poor quality due to its mushy texture. The fins are also considered to be of lower quality for use in shark fin soup, though are valuable enough that captured sharks are often finned at sea.[1] The carcasses may be processed into animal feed and fish meal, while the skin, cartilage, and jaws are also of value.[12][16]

The most significant longfin mako catches are by Japanese tropical longline fisheries, and those sharks occasionally enter Tokyo fish markets. From 1987 to 1994, United States fisheries reported catches (discarded, as this species is worthless on the North American market) of 2–12 tons per year.[1] Since 1999, retention of this species has been prohibited by the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service Fishery Management Plan for Atlantic sharks.[17] Longfin mako were once significant in the Cuban longline fishery, comprising one-sixth of the shark landings from 1971 to 1972; more recent data from this fishery are not available. The IUCN has assessed this species as "Vulnerable" due to its uncommonness, low reproductive rate, and susceptibility to shark fishing gear. It has also been listed under Annex I of the Convention on Migratory Species Migratory Shark Memorandum of Understanding.[18] In the North Atlantic, stocks of the shortfin mako have declined 40% or more since the late 1980s, and concerns exist that populations of the longfin mako are following the same trend.[1] In 2019, along with its relative the shortfin mako, the IUCN listed the longfin mako as "Endangered" due to continuing declines alongside 58 elasmobranch species.[3][4]

References

- Rigby, C.L.; Barreto, R.; Carlson, J.; Fernando, D.; Fordham, S.; Francis, M.P.; Jabado, R.W.; Liu, K.M.; Marshall, A.; Pacoureau, N.; Romanov, E.; Sherley, R.B.; Winker, H. (2019). "Isurus paucus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T60225A3095898. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T60225A3095898.en. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- "World's fastest shark endangered, 17 other species almost extinct, conservationists say". Fox News. 22 March 2019. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "The IUCN Announced Conservation Status Update on 58 Elasmobranch Species, Including the Shortfin Mako – Ocean for Sharks". Archived from the original on 2019-03-30. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

- "Press". Archived from the original on 2020-02-06. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

- Compagno, L.J.V. (2002). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date (Volume 2). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization. pp. 115–117. ISBN 92-5-104543-7.

- Ebert, D.A. (2003). Sharks, Rays, and Chimaeras of California. London: University of California Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 0-520-23484-7.

- Dosay-Abkulut, M. (2007). "What is the Relationship within the Family Lamnidae?" (PDF). Turkish Journal of Biology. 31: 109–113. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-20. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- Fitzgerald, E. (2004). "A review of the Tertiary fossil Cetacea (Mammalia) localities in Australia" (PDF). Memoirs of Museum Victoria. 61 (2): 183–208. doi:10.24199/j.mmv.2004.61.12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-08-23.

- Yabumoto, Y. & Uyeno, T. (1994). "Late Mesozoic and Cenozoic fish faunas of Japan". The Island Arc. 3 (4): 255–269. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1738.1994.tb00115.x. Archived from the original on 2019-03-30. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- Martin, R.A. Biology of the Longfin Mako (Isurus paucus) Archived 2019-09-02 at the Wayback Machine. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved on December 25, 2008.

- Wilson, T. and Ford, T. Biological Profiles: Longfin Mako Archived 2019-04-17 at the Wayback Machine. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on December 25, 2008.

- Bustamante, C., Concha, F., Balbontín, F., & Lamilla, J. (2009). Southernmost record of Isurus paucus Gitart Manday, 1966 (Elasmobranchii: Lamnidae) in the southeast Pacific Ocean. Revista de biología marina y oceanografía, 44(2), 523-526.

- Carey, F. G., Casey, J. G., Pratt, H. L., Urquhart, D., & McCosker, J. E. (1985). Temperature, heat production and heat exchange in lamnid sharks. Mem S Calif Acad Sci, 9, 92-108.

- Gilmore, R.G. (May 6, 1983). "Observations on the Embryos of the Longfin Mako, Isurus paucus, and the Bigeye Thresher, Alopias superciliosus". Copeia. American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists. 1983 (2): 375–382. doi:10.2307/1444380. JSTOR 1444380.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2008). "Isurus paucus" in FishBase. December 2008 version.

- Fowler, S.L.; Cavanagh, R.D.; Camhi, M.; Burgess, G.H.; Cailliet, G.M.; Fordham, S.V.; Simpfendorfer, C.A. & Musick, J.A. (2005). Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras: The Status of the Chondrichthyan Fishes. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. pp. 106–109. ISBN 2-8317-0700-5.

- Memorandum of Understanding – Migratory Sharks Archived 2013-04-20 at the Wayback Machine. Convention on Migratory Species. Downloaded on February 14, 2012.