Ian Gilmour, Baron Gilmour of Craigmillar

Ian Hedworth John Little Gilmour, Baron Gilmour of Craigmillar, PC (8 July 1926 – 21 September 2007) was a Conservative Party politician in the United Kingdom. He was styled Sir Ian Gilmour, 3rd Baronet from 1977, having succeeded to his father's baronetcy, until he became a life peer in 1992. He was Secretary of State for Defence in 1974, in the government of Edward Heath. In the government of Margaret Thatcher, he was Lord Privy Seal from 1979 to 1981.

The Lord Gilmour of Craigmillar | |

|---|---|

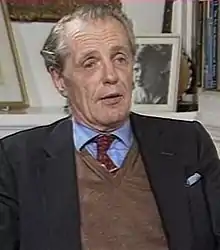

Gilmour being interviewed in 1985 | |

| Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal (Government spokesman for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs) | |

| In office 4 May 1979 – 11 September 1981 | |

| Prime Minister | Margaret Thatcher |

| Preceded by | The Lord Peart |

| Succeeded by | Humphrey Atkins |

| Shadow Secretary of State for Defence | |

| In office 15 January 1976 – 4 May 1979 | |

| Leader | Margaret Thatcher |

| Preceded by | George Younger |

| Succeeded by | Fred Mulley |

| In office 11 March 1974 – 29 October 1974 | |

| Leader | Ted Heath |

| Preceded by | Fred Peart |

| Succeeded by | Peter Walker |

| Shadow Home Secretary | |

| In office 18 February 1975 – 15 January 1976 | |

| Leader | Margaret Thatcher |

| Preceded by | Keith Joseph |

| Succeeded by | Willie Whitelaw |

| Shadow Secretary of State for Northern Ireland | |

| In office 29 October 1974 – 18 February 1975 | |

| Leader | Ted Heath |

| Preceded by | Francis Pym |

| Succeeded by | Airey Neave |

| Secretary of State for Defence | |

| In office 8 January 1974 – 4 March 1974 | |

| Prime Minister | Ted Heath |

| Preceded by | Peter Carrington |

| Succeeded by | Roy Mason |

| Minister for Defence Procurement | |

| In office 7 April 1971 – 8 January 1974 | |

| Prime Minister | Ted Heath |

| Preceded by | Robert Lindsay |

| Succeeded by | George Younger |

| Member of Parliament for Central Norfolk | |

| In office 23 November 1962 – 8 February 1974 | |

| Preceded by | Richard Collard |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Member of Parliament for Chesham and Amersham | |

| In office 28 February 1974 – 16 March 1992 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency created |

| Succeeded by | Cheryl Gillan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ian Hedworth John Little Gilmour 8 July 1926 London, England |

| Died | 21 September 2007 (aged 81) London, England |

| Political party | Conservative and National Liberal (before 1964) Conservative (1964-1999) Pro-Euro Conservative (1999–2001) Liberal Democrats (after 2001) |

| Spouse |

Lady Caroline Montagu-Douglas-Scott

(m. 1951; died 2004) |

| Children | 5, including David and Oliver |

| Relatives | Tim Bouverie (grandson) |

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford City Law School |

Early life

Gilmour was the son of stockbroker Lieutenant Colonel Sir John Gilmour, 2nd Baronet, and his wife, Victoria, a granddaughter of the 5th Earl Cadogan. His parents divorced in 1929, and his father married Mary, the eldest daughter of the 3rd Duke of Abercorn. The family had land in Scotland and he inherited a substantial estate and shares in Meux's Brewery from his grandfather, Admiral of the Fleet, the Hon. Sir Hedworth Meux.[1]

They lived in the grounds of Syon Park in London, with a house in Tuscany. He was educated at Eton College and read history at Balliol College, Oxford.

He served with the Grenadier Guards from 1944 to 1947. He was called to the bar at Inner Temple in 1952 and was a tenant in the chambers of Quintin Hogg for two years. He bought The Spectator in 1954 and was its editor from 1954 to 1959. He sold The Spectator to the businessman Harold Creighton in 1967. His editorship of the magazine is seen as one of the highlights of that paper's long history.

Member of Parliament

He was elected as Member of Parliament for Central Norfolk in a by-election in 1962, winning by 220 votes. He held this seat until 1974, when his seat was abolished due to boundary changes, and he stood for the safe Conservative seat of Chesham and Amersham, sitting as its MP from 1974 until his retirement in 1992.

In parliament, he was a social liberal, voting to abolish the death penalty, and legalise abortion and homosexuality. He also supported the campaign to join the EEC. He was Parliamentary Private Secretary to Quintin Hogg from 1963. He was one of the few members to vote against the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968, regarding it as racist and designed to "keep the blacks out".[2]

Gilmour espoused the Arab cause when it was less popular in progressive circles than it later became and supported it throughout his years in the House of Commons, where his chief ally was Dennis Walters.[3]

In government

He served in Edward Heath's government from 1970, holding a variety of junior positions in the Ministry of Defence under Lord Carrington: Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for the Army from 1970 to 1971, then Minister of State for Defence Procurement until 1972, then Minister of State for Defence. He joined the Privy Council in 1973. He replaced Carrington in January 1974 to join Heath's Cabinet as Defence Secretary, but lost his position after Labour won the most seats in the general election at the end of February. He was in the Shadow Cabinet after the general election in February 1974 as Shadow Defence Secretary to late 1974. From the end of 1974 to February 1975 he was Shadow Northern Ireland Secretary.

In opposition, Gilmour joined the Conservative Research Department. With Chris Patten, he wrote the Conservative Party manifesto for the October 1974 election – a second loss, by a wider margin. When Margaret Thatcher became the new leader of the Conservative party, she appointed Gilmour as Shadow Home Secretary in 1975, then as Shadow Defence Secretary from 1976 to 1978. He became Lord Privy Seal after the 1979 general election, as the chief Government spokesman in the House of Commons for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, working again under Lord Carrington, who, as Foreign Secretary, sat in the House of Lords. He co-chaired with Carrington the Lancaster House talks, which led to the end of Ian Smith's government in Rhodesia, and the creation of an independent Zimbabwe under Robert Mugabe. He also negotiated with the EEC to reduce Britain's financial contribution.

Backbenches and retirement

Gilmour did not enjoy good relations with Margaret Thatcher. Thatcher remarked in her autobiography, somewhat sarcastically: "Ian remained at the Foreign Office for two years. Subsequently, he was to show me the same loyalty from the back-benches as he had in government."[4] He survived a reshuffle in January 1981, but was sacked on 14 September 1981. He announced that the government was "steering full speed ahead for the rocks", and said that he regretted that he had not resigned beforehand.

Gilmour was a moderate who disagreed with the economic policies of Prime Minister Thatcher. He became the most outspoken "wet". During a lecture at Cambridge in February 1980, Gilmour contended:

- "In the conservative view, economic liberalism à la Professor Hayek, because of its starkness and its failure to create a sense of community, is not a safeguard of political freedom but a threat to it."[5]

Gilmour remained on the backbenches until 1992, and opposed many Thatcherite policies, including the abolition of the Greater London Council, rate-capping and the poll tax. He was in favour of proportional representation. In 1989, he was considered by discontented backbenchers as a possible future leader; in the event, he supported Sir Anthony Meyer in his leadership challenge in December 1989. However, he did not participate in frontline British politics again, and was given a life peerage by John Major on 25 August 1992, becoming Baron Gilmour of Craigmillar, of Craigmillar in the District of the City of Edinburgh,[6] of which his family were, for several hundred years, the feudal superiors.

He was expelled from the Conservative Party in 1999 for supporting the Pro-Euro Conservative Party in the European Parliament elections. At Question Time on 23 June 1999, Prime Minister Tony Blair described this move as a demonstration of how right-wing and anti-European the Conservative Party had become.

Writings

Gilmour was known for writing coherently from the One Nation perspective of the Conservative Party, in opposition to Thatcherism; in particular in his books Dancing with Dogma (1992) and (with Mark Garnett) Whatever Happened to the Tories (1997), and in his critical articles in journals such as the London Review of Books.

His book, Inside Right (1977) is an introduction to conservative thought and thinkers. He also wrote the books The Body Politic (1969), Britain Can Work (1983), Riot, Risings and Revolution (1992), and The Making of the Poets: Byron and Shelley in Their Time (2002).[7]

He was president of Medical Aid for Palestinians from 1993 to 1996, and was chairman of the Byron Society from 2003 until his death.

Personal life

On 10 July 1951, Gilmour married Lady Caroline Margaret Montagu-Douglas-Scott, the youngest daughter of the 8th Duke of Buccleuch and sister of John Scott, 9th Duke of Buccleuch. Their wedding was attended by several members of the British Royal Family, including Queen Mary, Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother), and the future Elizabeth II. They lived in Isleworth, and had four sons and one daughter. On 22 February 1974, Lady Caroline Gilmour launched HMS Cardiff.[8] His wife died in 2004, but he was survived by their five children, the eldest of whom, the Hon. David Gilmour, succeeded to his father's baronetcy. Among the younger sons, Oliver Gilmour is a conductor and Andrew Gilmour (UN official) is a senior United Nations official.

His grandson is the British historian Tim Bouverie.

Death

Lord Gilmour died on 21 September 2007 of undisclosed causes, aged 81, at West Middlesex Hospital, Isleworth, Greater London, after a short illness.[7]

Cultural portrayals

- Gilmour was portrayed by Pip Torrens in The Iron Lady, a 2011 biographical film of Margaret Thatcher. In the film, Gilmour voices his concern over the decline of manufacturing in the UK.

Arms

|

|

References

- "History in Portsmouth". History in Portsmouth. 20 September 1929. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "When Labour played the racist card". www.newstatesman.com.

- "When Labour played the racist card". www.newstatesman.com. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- Margaret Thatcher, The Downing Street Years (HarperCollins, 1993), p. 29.

- Hugo Young, One of Us (1989) p 200

- "No. 53032". The London Gazette. 28 August 1992. p. 14593.

- "Lord Gilmour's BBC online obituary". Newsvote.bbc.co.uk. 21 September 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "Visiting British Naval Ships British High Commission, Accra". www.britishhighcommission.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 18 August 2004. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- Debrett's Peerage. 2003. p. 642.

_(2022).svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)