Lordship of Ireland

The Lordship of Ireland (Irish: Tiarnas na hÉireann), sometimes referred to retroactively as Anglo-Norman Ireland, was the part of Ireland ruled by the King of England (styled as "Lord of Ireland") and controlled by loyal Anglo-Norman lords between 1177 and 1542. The lordship was created following the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169–1171. It was a papal fief, granted to the Plantagenet kings of England by the Holy See, via Laudabiliter. As the Lord of Ireland was also the King of England, he was represented locally by a governor, variously known as the Justiciar, Lieutenant, Lord Lieutenant or Lord Deputy.

Lordship of Ireland | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1177–1542 | |||||||||

The Lordship of Ireland (pink) in 1300. | |||||||||

| Status | Papal possession held in fief by the King of England | ||||||||

| Capital | Dublin2 | ||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | ||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | ||||||||

| Lord | |||||||||

• 1177–1216 | John (first) | ||||||||

• 1509–1542 | Henry VIII (last) | ||||||||

| Lord Lieutenant | |||||||||

• 1316–1318 | Roger Mortimer (first) | ||||||||

• 1529–1534 | Henry FitzRoy (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||

| House of Lords | |||||||||

| House of Commons | |||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Established | May 1177 | ||||||||

| June 1542 | |||||||||

| Currency | Irish pound | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | IE | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

1A commission of Edward IV into the arms of Ireland found these to be the arms of the Lordship. The blazon is Azure, three crowns in pale Or, bordure Argent. Typically, bordered arms represent the younger branch of a family or maternal descent.[1][2] 2Although Dublin was the capital, parliament was held in other towns at various times. | |||||||||

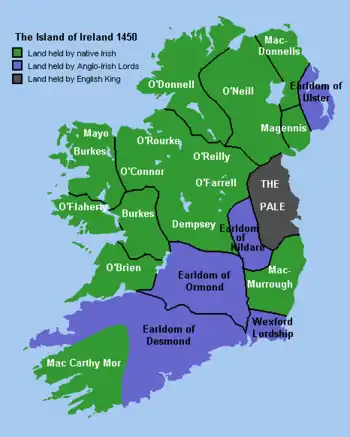

The kings of England claimed lordship over the whole island, but in reality the king's rule only ever extended to parts of the island. The rest of the island – referred to subsequently as Gaelic Ireland – remained under the control of various Gaelic Irish kingdoms or chiefdoms, who were often at war with the Anglo-Normans.

The area under English rule and law grew and shrank over time, and reached its greatest extent in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. The lordship then went into decline, brought on by its invasion by Scotland in 1315–18, the Great Famine of 1315–17, and the Black Death of the 1340s. The fluid political situation and Norman feudal[3] system allowed a great deal of autonomy for the Anglo-Norman lords in Ireland, who carved out earldoms for themselves and had almost as much authority as some of the native Gaelic kings. Some Anglo-Normans became Gaelicised and rebelled against the English administration. The English attempted to curb this by passing the Statutes of Kilkenny (1366), which forbade English settlers from taking up Irish law, language, custom and dress. The period ended with the creation of the Kingdom of Ireland in 1542.

History

Arrival of the Normans in Ireland

The authority of the Lordship of Ireland's government was seldom extended throughout the island of Ireland at any time during its existence but was restricted to the Pale around Dublin, and some provincial towns, including Cork, Limerick, Waterford, Wexford and their hinterlands. It owed its origins to the decision of a Leinster dynast, Diarmait Mac Murchada (Diarmuid MacMorrough), to bring in a Norman knight based in Wales, Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (alias 'Strongbow'), to aid him in his battle to regain his throne, after being overthrown by a confederation led by the new Irish High King (the previous incumbent had protected MacMurrough). Henry II of England invaded Ireland to control Strongbow, who he feared was becoming a threat to the stability of his own kingdom on its western fringes (there had been earlier fears that Saxon refugees might use either Ireland or Flanders as a base for a counter-offensive after 1066); much of the later Plantagenet consolidation of South Wales was in furtherance of holding open routes to Ireland.

Henry Plantagenet and Laudabiliter

From 1155 Henry claimed that Pope Adrian IV had given him authorisation to reform the Irish church by assuming control of Ireland. Religious practices and ecclesiastical organisation in Ireland had evolved divergently from those in areas of Europe influenced more directly by the Holy See, although many of these differences had been eliminated or greatly lessened by the time the bull was issued in 1155.[4] Further, the former Irish church had never sent its dues ("tithes") to Rome. Henry's primary motivation for invading Ireland in 1171 was to control Strongbow and other Norman lords. In the process he accepted the fealty of the Gaelic kings at Dublin in November 1171 and summoned the Synod of Cashel in 1172, this bringing the Irish Church into conformity with English and European norms.

In 1175 the Treaty of Windsor was agreed by Henry and Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair, High King of Ireland.[5]

The popes asserted the right to grant sovereignty over islands to different monarchs on the basis of the Donation of Constantine (now known to be a forgery). Doubts were cast by eminent scholars on Laudabiliter itself in the 19th century, but it had been confirmed by the letters of Pope Alexander III. The Papal power to grant also fell within the remit of Dictatus papae (1075–1087). While Laudabiliter had referred to the "kingdom" of Ireland, the Papacy was ambiguous about continuing to describe it as a kingdom as early as 1185.

John Lackland as Lord of Ireland

Having captured a small part of Ireland on the east coast, Henry used the land to solve a dispute dividing his family. For he had divided his territories between his sons, with the youngest being nicknamed Johan sanz Terre (in English, "John Lackland") as he was left without lands to rule. At the Oxford parliament in May 1177, Henry replaced William FitzAldelm and granted John his Irish lands, so becoming Lord of Ireland (Dominus Hiberniae) in 1177 when he was 10 years old, with the territory being known in English as the Lordship of Ireland.

Henry had wanted John to be crowned King of Ireland on his first visit in 1185, but Pope Lucius III specifically refused permission, citing the dubious nature of a claim supposedly provided by Pope Adrian IV years earlier.[6] "Dominus" was the usual title of a king who had not yet been crowned, suggesting that it was Henry's intention. Lucius then died while John was in Ireland, and Henry obtained consent from Pope Urban III and ordered a crown of gold and peacock feathers for John. In late 1185 the crown was ready, but John's visit had by then proved a complete failure, so Henry cancelled the coronation.[7]

Following the deaths of John's older brothers he became King of England in 1199, and so the Lordship of Ireland, instead of being a separate country ruled by a junior Norman prince, came under the direct rule of the Angevin crown. In the legal terminology of John's successors, the "lordship of Ireland" referred to the sovereignty vested in the Crown of England; the corresponding territory was referred to as the "land of Ireland".[8]

Perennial struggle with Gaeldom

| History of Ireland |

|---|

|

|

|

The Lordship thrived in the 13th century during the Medieval Warm Period, a time of warm climate and better harvests. The feudal system was introduced, and the Parliament of Ireland first sat in 1297. Some counties were created by shiring, while walled towns and castles became a feature of the landscape. But little of this engagement with mainstream European life was of benefit to those the Normans called the "mere Irish". "Mere" derived from the Latin merus, meaning "pure". Environmental decay and deforestation continued unabated throughout this period, being greatly exacerbated by the English newcomers and an increase in population.

The Norman élite and churchmen spoke Norman French and Latin. Many poorer settlers spoke English, Welsh, and Flemish. The Gaelic areas spoke Irish dialects. The Yola language of County Wexford was a survivor of the early English dialects. The Kildare Poems of c. 1350 are a rare example of humorous local culture written in Middle English.

The Lordship suffered invasion from Scotland by Edward Bruce in 1315–1318, which destroyed much of the economy and coincided with the great famine of 1315–1317. The earldom of Ulster ended in 1333, and the Black Death of 1348–1350 impacted more on the town-dwelling Normans than on the remaining Gaelic clans. The Norman and English colonists exhibited a tendency to adopt much of the native culture and language, becoming "Gaelicized" or in the words of some "More Irish than the Irish themselves". In 1366 the Statute of Kilkenny tried to keep aspects of Gaelic culture out of the Norman-controlled areas albeit in vain. As the Norman lordships became increasingly Gaelicized and made alliances with native chiefs, whose power steadily increased, crown control slowly eroded.

Additionally, the Plantagenet government increasingly alienated the Irish chiefs and people on whom they often relied for their military strength. It had been a common practice for the Norman lordships as well as government forces to recruit the native Irish who were allied to them or living in English controlled areas (i.e. Leinster including Meath and Ossory, Munster and some parts of Connacht). This was easy to do as the native Irish had no great sense of national identity at that time and were prone to mercenarism and shifting alliances. But the Irish chiefs became increasingly alienated by the oppressive measures of the English government and began openly rebelling against the crown. Some of the more notable among those clans who had formerly cooperated with the English but became increasingly alienated until turning openly anti-Norman and a thorn in the side of the Dublin administration were the O'Connor Falys, the MacMurrough-Kavanagh dynasty (Kingdom of Leinster), the Byrnes and the O'Mores of Leix. These clans were able to successfully defend their territories against English attack for a very long time through the use of asymmetrical guerrilla warfare and devastating raids into the lands held by the colonists. Additionally, the power of native chiefs who had never come under English domination such as the O'Neills and the O'Donnells increased steadily until these became once again major power players on the scene of Irish politics. Historians refer to a Gaelic revival or resurgence as occurring between 1350 and 1500, by which time the area ruled for the Crown – "the Pale" – had shrunk to a small area around Dublin.

Between 1500 and 1542 a mixed situation arose. Most clans remained loyal to the Crown most of the time, at least in theory, but using a Gaelic-style system of alliances based on mutual favours, centered on the Lord Deputy who was usually the current Earl of Kildare. The Battle of Knockdoe in 1504 saw such a coalition army fight the Burkes in Galway. However, a rebellion by the 9th Earl's heir Silken Thomas in 1535 led on to a less sympathetic system of rule by mainly English-born administrators. The end of this rebellion and Henry VIII's seizure of the Irish monasteries around 1540 led on to his plan to create a new kingdom based on the existing parliament.

Transformation into a Kingdom

English monarchs continued to use the title "Lord of Ireland" to refer to their position of conquered lands on the island of Ireland. The title was changed by the Crown of Ireland Act passed by the Irish Parliament in 1542 when, on Henry VIII's demand, he was granted a new title, King of Ireland, with the state renamed the Kingdom of Ireland. Henry VIII changed his title because the Lordship of Ireland had been granted to the Norman monarchy by the Papacy; Henry had been excommunicated by the Catholic Church and worried that his title could be withdrawn by the Holy See. Henry VIII also wanted Ireland to become a full kingdom to encourage a greater sense of loyalty amongst his Irish subjects, some of whom took part in his policy of surrender and regrant. To provide for greater security, a Royal Irish Army was established.

Parliament

The government was based in Dublin, but the members of Parliament could be summoned to meet anywhere, whether Dublin or Kilkenny:

- 1310 Kilkenny

- 1320 Dublin

- 1324 Dublin

- 1327 Dublin

- 1328 Kilkenny

- 1329 Dublin

- 1330 Kilkenny

- 1331 Kilkenny

- 1331 Dublin

- 1341 Dublin

- 1346 Kilkenny

- 1350 Kilkenny

- 1351 Kilkenny

- 1351 Dublin

- 1353 Dublin

- 1357 Kilkenny

- 1359 Kilkenny

- 1359 Waterford

- 1360 Kilkenny

- 1366 Kilkenny

- 1369 Dublin

See also

References

- Perrin, WG; Vaughan, Herbert S (1922), British Flags. Their Early History and their Development at Sea; with an Account of the Origin of the Flag as a National Device, Cambridge, ENG, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 51–2.

- Chambers's Encyclopædia: A Dictionary of Universal Knowledge, 1868, p. 627,

The insignia of Ireland have variously been given by early writers. In the reign of Edward IV, a commission appointed to enquire what were the arms of Ireland found them to be "three crowns in pale". It has been supposed that these crowns were abandoned at the Reformation, from an idea that they might denote the feudal sovereignty of the pope, whose vassal the king of England was, as lord of Ireland

. - "The Norman Feudal System". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- Poole, Austin Lane (1993), From Domesday book to Magna Carta, 1087–1216, Oxford University Press, p. 303.

- Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí (2013), Early Medieval Ireland, 400-1200, London: Routledge, p. 6,

1175: Treaty of Windsor between Ruaidri Ua Conchobhair, high-king, and Henry II. 1183: Ruaidri Ua Conchobhair deposed.

- McLoughlin, William (1906), Pope Adrian IV, a Friend of Ireland, Cork, IE: Browne and Nolan, p. 100.

- Warren, WL (1960), King John, London, ENG, UK: Eyre & Spottiswoode, p. 35.

- Lydon, James (May 1995). "Ireland and the English Crown, 1171-1541". Irish Historical Studies. Cambridge University Press. 29 (115): 281–294 : 282. doi:10.1017/S0021121400011834. JSTOR 30006815. S2CID 159713467.