Louis D. DeSaussure

Louis Daniel DeSaussure (May 19, 1824 – June 20, 1888), scion of a historic and wealthy South Carolina family, was the most important and prosperous slave broker in the city of Charleston in the years immediately preceding the American Civil War. After the military defeat of the Confederacy he worked as an investment broker, president of a phosphate-mining company, and director of a regional railroad. During Reconstruction he was an activist in support of Democratic (Third Party System) South Carolina politicians such as Wade Hampton III.

Biography

Louis D. DeSaussure was the son of Henry Alexander DeSaussure and Susan Gibbes Boone and thus a member of the socially prominent American branch of the De Saussure family; his grandfather was Henry William de Saussure, his uncle was U.S. Senator William Ford De Saussure, brother was Wilmot Gibbes de Saussure, etc., etc.[1]

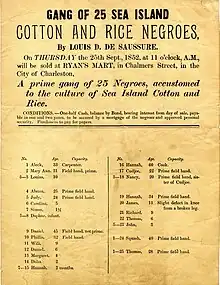

On July 1, 1846, DeSaussure announced in the Charleston Daily Courier, "The subscriber has this day commenced business as a BROKER AUCTIONEER AND COMMISSION AGENT and will attend to the selling of houses, lands, negroes, stocks, &c. office 5 State-st next door to Rail Road office."[2] According to scholar Michael Tadman, DeSaussure was part of the class of slave dealers "who essentially acted as auctioneers rather than as buyers and sellers in their own right."[3] At the time of the 1850 U.S. federal census, L.D. Saussure, occupation broker, was living in parishes of St. Philip and St. Michael in the District of Charleston, in the household of his father Henry A. DeSaussure, attorney-at-law, in company with his wife and their young child, D. L. Saussure.[4] By January 16, 1855, his business was seemingly thriving as he was advertising five forthcoming sales to be held north of the Exchange: a laborer named Isaac, about 45 years old; an estate sale of stocks including shares in the Greenville Railroad; an estate sale of 93 rice-field negroes; an estate sale of about 70 negroes "accustomed to the culture of long-staple cotton and provisions"; and an estate sale of a "prime gang of 60 negroes accustomed to the culture of cotton and provisions."[5] In 1856, traders DeSaussure, Ziba B. Oakes, and Alonzo J. White opposed a new South Carolina law requiring that slave sales take place indoors rather than on the streets. Their argument was that the law was "an impolitic admission that would give 'strength to the opponents of slavery' and 'create among some portions of the community a doubt as to the moral right of slavery itself.'"[6] According to Frederic Bancroft in Slave-Trading in the Old South (1931):[1]

A count of DeSaussure's advertisements in the Courier alone, carefully excluding repetitions and transfers from private to public sales, shows that he obtained commissions on not less than 193 slaves in January, 1860, and on more than 259 in February...His gains from sales of slaves and various other kinds of property were almost princely, for that time. The income of no other "broker," of no professional man, and of few, if any, merchants, equaled his...DeSaussure's commissions alone for 1860 were US$10,983 (equivalent to $357,720 in 2022). Not all, but most of it, came from slave-trading. The next prosperous "broker" earned a little more than three-fourths as much, and none of the others exceeded $5,000, which was a large business income for that time and place; half of it sufficed for a generously comfortable living.[1]

Broker was the euphemism commonly used in Charleston to describe slave traders.[1] DeSaussure was one of the brokers who made use of the building now known as the Old Slave Mart.[7] At the time of the 1860 census, DeSaussure was a resident of Charleston, occupation broker, real estate valued at $20,000, personal estate valued at $25,000.[8] During the American Civil War he was a captain in the 3rd Regiment, South Carolina Cavalry.[9] In 1866 he paid $27 in taxes on $867 in cotton.[10]

In 1870, DeSaussure lived in the first ward of the city, occupation real estate broker, with his wife, five children aged six to 12, three female domestic servants born in Ireland, and two male domestic servants born in South Carolina.[11] At that time, DeSaussure owned real estate valued at $25,000 and personal property worth $10,000.[11] In 1872, DeSaussure was president of the Atlantic Phosphate Company, dealers in "first-class fertilizer."[12] He also continued to work as a broker, now specializing in "the Sale and Purchase of Stocks, Bonds, Real Estate and Loaning of Money."[12] In 1876 he called to order a "great meeting" at the Hibernian Hall in Charleston that passed a resolution refusing to pay taxes to any state government but one led by ex-Confederate general Wade Hampton III.[13] In 1877 he was vice president of the gentlemen's' auxiliary association of the Charleston City Hospital.[14] In 1880, DeSaussure's declared occupation was "broker, money," and one of his nearest neighbors was the physician and chemist St. Julien Ravenel.[15]

DeSaussure died in 1888 at age 64 and was memorialized in the first issue of the Transactions of the Huguenot Society of South Carolina, which described his business career as follows:[16]

Mr. DeSaussure began his mercantile life with the house of Messrs. Tobias & Co., and shortly after entered into business on his own account, as Broker and Real Estate Agent, and soon took a high position as a capable and prudent man of business. He was a director of the South Carolina Railroad for many years, and occupied similar positions of trust and responsibility on boards of various public companies. In his home he was most hospitable, and delighted in those exhibitions of courtesy, which are grateful to sojourners in a strange city.

After the Confederacy's defeat in the American Civil War, many "white Charlestonians displayed historical amnesia" about the institution of slavery.[6] A Liverpool-based scholar concurs that "for South Carolina and the South generally much of the slave trade is missing from the historical record [but] slave trading and the forcible separation of slave families were pervasive in South Carolina [and] traders tended to be men of considerable wealth and status."[3] The Huguenot Society, which DeSaussure joined on April 13, 1885, was apparently one of the local entities that produced post-war obituaries and biographies that scrubbed "clean the records of...leading South Carolina slave dealers."[6]

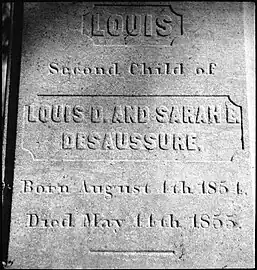

DeSaussure married his first cousin Sarah E. DeSaussure. Their children were Sarah M. DeSaussure, L. D. DeSaussure, F. R. DeSaussure, William B. DeSaussure, Mrs. J. B. Chisolm, and Mrs. Charles E. Fuller.[16]

Additional images

Gravestone of one of DeSaussure's children, who lived from 1854 to 1855

Gravestone of one of DeSaussure's children, who lived from 1854 to 1855 Southeast corner view of historic Louis DeSaussure House at 1 East Battery in Charleston

Southeast corner view of historic Louis DeSaussure House at 1 East Battery in Charleston

See also

References

- Bancroft, Frederic (2023) [1931, 1996]. "Chapter VIII. In Charleston". Slave Trading in the Old South. Southern Classics Series. Introduction by Michael Tadman. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-64336-427-8. LCCN 95020493. OCLC 1153619151.

- "The subscriber has this day commenced". The Charleston Daily Courier. 1846-07-01. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- Tadman, Michael (1996). "The Hidden History of Slave Trading in Antebellum South Carolina: John Springs III and Other "Gentlemen Dealing in Slaves"". The South Carolina Historical Magazine. 97 (1): 6–29. ISSN 0038-3082. JSTOR 27570133.

- The National Archives in Washington D.C.; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M432; Residence Date: 1850; Home in 1850: St Michael and St Phillip, Charleston, South Carolina; Roll: 850; Page: 151b via Ancestry.com

- "Sales by Louis D. DeSaussure". The Charleston Mercury. 1855-01-16. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- Kytle, Ethan J.; Roberts, Blain (2018). Denmark Vesey's garden: slavery and memory in the cradle of the Confederacy. New York: The New Press. pp. 34–35, 272–273. ISBN 9781620973660. LCCN 2017041546.

- "Louis D. DeSaussure slave sale broadside", Lowcountry Digital Library, South Carolina Historical Society, 2015 [1860], MSS 11-260-05-03, retrieved 2023-08-13

- The National Archives in Washington D.C.; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M653; Residence Date: 1860; Home in 1860: Charleston Ward 1, Charleston, South Carolina; Roll: M653_1216; Page: 213; Family History Library Film: 805216 - via Ancestry.com

- "Southern historical society papers. v.26 1898". HathiTrust. pp. 73–74. hdl:2027/msu.31293022978666. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- The National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.; Internal Revenue Assessment Lists for South Carolina, 1864-1866; Series: M789; Roll: 2; Description: District 2; Monthly and Special Lists; Aug 1865-Dec 1866; Record Group: 58, Records of the Internal Revenue Service, 1791 - 2006 via Ancestry.com

- Source Citation Year: 1870; Census Place: Charleston Ward 1, Charleston, South Carolina; Roll: M593_1486; Page: 3A Source Information Ancestry.com. 1870 United States Federal Census[database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch.

- "The Charleston city guide". HathiTrust. 1872. hdl:2027/loc.ark:/13960/t5bc48167. Page images 6 & 14. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- "Hampton and his Red shirts; South Carolina's deliverance in 1876, by Alfred B. Williams". HathiTrust. p. 428. hdl:2027/inu.32000002647255. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- "Sholes' directory of the city of Charleston". HathiTrust. 1877. p. 47. hdl:2027/emu.010002588208. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- Source Citation - Year: 1880; Census Place: Charleston, Charleston, South Carolina; Roll: 1221; Page: 1A; Enumeration District: 052 Source Information - Ancestry.com and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 1880 United States Federal Census[database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010.

- "Transactions of the Huguenot Society of South Carolina. v.1-3(1885-1894)". HathiTrust. p. 47. hdl:2027/uiug.30112114048397. Retrieved 2023-08-13.