Louis Riel

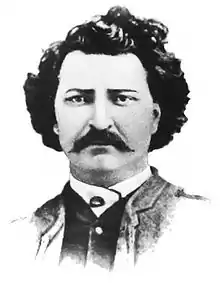

Louis Riel (/ˈluːi riˈɛl/; French: [lwi ʁjɛl]; 22 October 1844 – 16 November 1885) was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political leader of the Métis people. He led two resistance movements against the Government of Canada and its first prime minister John A. Macdonald. Riel sought to defend Métis rights and identity as the Northwest Territories came progressively under the Canadian sphere of influence.

Louis Riel | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of the Provisional Government, then, Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia | |

| In office 27 December 1869 – 24 June 1870 | |

| Member of Parliament for Provencher | |

| In office 13 October 1873 – 16 April 1874 | |

| Preceded by | George-Étienne Cartier |

| In office 13 September 1874 – 25 February 1875 | |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Bannatyne |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 22 October 1844 St. Boniface, Red River Colony, Rupert's Land |

| Died | 16 November 1885 (aged 41) Regina, North-West Territories, Canada |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature |  |

The first resistance movement led by Riel was the Red River Resistance of 1869–1870. The provisional government established by Riel ultimately negotiated the terms under which the new province of Manitoba entered the Canadian Confederation. However, while carrying out the resistance, Riel had a Canadian nationalist, Thomas Scott, executed. Riel soon fled to the United States to escape prosecution. He was elected three times as member of the House of Commons, but, fearing for his life, he could never take his seat. During these years in exile he came to believe that he was a divinely chosen leader and prophet. He married in 1881 while in exile in the Montana Territory.

In 1884 Riel was called upon by the Métis leaders in Saskatchewan to help resolve longstanding grievances with the Canadian government, which led to an armed conflict with government forces: the North-West Rebellion of 1885. Defeated at the Battle of Batoche, Riel was imprisoned in Regina where he was convicted at trial of high treason. Despite protests, popular appeals and the jury's call for clemency, Riel was executed by hanging. Riel was seen as a heroic victim by French Canadians; his execution had a lasting negative impact on Canada, polarizing the new nation along ethno-religious lines. The Métis were marginalized in the Prairie provinces by the increasingly English-dominated majority. A long-term impact was the bitter alienation Francophones across Canada felt, and anger against the repression by their countrymen.[1]

Riel's historical reputation has long been polarized between portrayals as a dangerous religious fanatic and rebel opposed to the Canadian nation, and, by contrast, as a charismatic leader intent on defending his Métis people from the unfair encroachments by the federal government eager to give Orangemen-dominated Ontario settlers priority access to land. Riel has received among the most formal organizational and academic scrutiny of any figure in Canadian history.[2]

Early life

The Red River Settlement was a Rupert's Land territory administered by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). At the mid-19th-century the settlement was largely inhabited by Métis people of mixed First Nations-European descent whose ancestors were for the most part Scottish and English men married to Cree women and French-Canadian men married to Saulteaux (plains Ojibwe) women.[3]

Louis Riel was born in 1844 in his grandparents' small one-room home in St-Boniface near the fork of the Red and Seine rivers.[4][5] Riel was the eldest of eleven children in a locally well-respected family. His father, who was of Franco-Chipewyan Métis descent, had gained prominence in this community by organizing a group that supported Guillaume Sayer, a Métis arrested and tried for challenging the HBC's historical trade monopoly.[6][7] Sayer's eventual release due to agitations by Louis Sr.'s group effectively ended the monopoly, and the name Riel was therefore well known in the Red River area. His mother was the daughter of Jean-Baptiste Lagimodière and Marie-Anne Gaboury, one of the earliest European-descended families to settle in Red River in 1812. The Riels were noted for their devout Catholicism and strong family ties.[8][9]

Riel began his schooling at age seven,[10][11] and by age ten he attended St. Boniface Catholic schools, including eventually a school run by the French Christian Brothers.[12] At age thirteen he came to the attention of Bishop Alexandre Taché who was eagerly promoting the priesthood for talented young Métis.[6] In 1858 Taché arranged for Riel to attend the Petit Séminaire de Montréal.[6] Descriptions of him at the time indicate that he was a fine scholar of languages, science, and philosophy.[13] While a good student, he was also hot-tempered, extreme in his views, intolerant of criticism and opposition, and not opposed to arguing with his teachers.[14]

Following news of his father's premature death in 1864, Riel lost interest in the priesthood and withdrew from the college in March 1865. For a time, he continued his studies as a day student in the convent of the Grey Nuns, but was soon asked to leave, following breaches of discipline.[12] During Riel's period of mourning of his father, he believed that Louis Riel was dead and he himself was David Mordecai, a Jew from Marseilles, and as David, he was not eligible to the immense inheritance of his father (which, in fact, was of little value). Seized with religious fervour, he announced that he was going to form a new religious movement.[14] He remained in Montreal for over a year, living at the home of his aunt, Lucie Riel. Impoverished by the death of his father, Riel took employment as a law clerk in the Montreal office of Rodolphe Laflamme.[6][15] During this time he was involved in a failed romance with a young woman named Marie–Julie Guernon. This progressed to the point of Riel having signed a contract of marriage, but his fiancée's family opposed her involvement with a Métis, and the engagement was soon broken. Compounding this disappointment, Riel found legal work unpleasant and, by early 1866, he had resolved to leave Canada East.[12][16][17] Some of his friends said later that he worked odd jobs in Chicago, while staying with poet Louis-Honoré Fréchette,[18] and wrote poems himself in the manner of Lamartine, and that he was briefly employed as a clerk in Saint Paul, Minnesota, before returning to the Red River settlement on 26 July 1868.[19]

Red River Resistance

The majority population of the Red River had historically been Métis and First Nations people. Upon his return, Riel found that religious, nationalistic, and racial tensions were exacerbated by an influx of Anglophone Protestant settlers from Ontario. The political situation was also uncertain, as ongoing negotiations for the transfer of Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company to Canada had not addressed the political terms of transfer.[6][20] Bishop Taché and the HBC governor William Mactavish both warned the Macdonald government that the lack of consultation and consideration of Métis views would precipitate unrest.[21][22] Finally, the Canadian minister of public works, William McDougall, ordered a survey of the area. The arrival of a survey party on 20 August 1869 increased anxiety among the Métis as the survey was being carried out as a grid system of townships (an American system) that cut across existing Métis river lots.[20][23][24]

In late August, Riel denounced the survey in a speech, and on 11 October 1869, the survey's work was disrupted by a group of Métis that included Riel.[6] This group organized itself as the "National Committee of the Métis" on 16 October, with Riel as secretary and John Bruce as president.[25] When summoned by the HBC-controlled Council of Assiniboia to explain his actions, Riel declared that any attempt by Canada to assume authority would be contested unless Ottawa had first negotiated terms with the Métis. Nevertheless, the non-bilingual McDougall was appointed the lieutenant governor-designate, and attempted to enter the settlement on 2 November. McDougall's party was turned back near the Canada–US border, and on the same day, Métis led by Riel seized Fort Garry.[26][27][6][22]

On 6 November, Riel invited Anglophones to attend a convention alongside Métis representatives to discuss a course of action, and on 1 December he proposed to this convention a list of rights to be demanded as a condition of union. Much of the settlement came to accept the Métis point of view, but a passionately pro-Canadian minority began organizing in opposition.[6][22] Loosely constituted as the Canadian Party, this group was led by John Christian Schultz, Charles Mair, Colonel John Stoughton Dennis, and a more reticent Major Charles Boulton.[28] McDougall attempted to assert his authority by authorizing Dennis to raise a contingent of armed men, but the Anglophone settlers largely ignored this call to arms. Schultz, however, attracted approximately fifty recruits and fortified his home and store. Riel ordered Schultz's home surrounded, and the outnumbered Canadians soon surrendered and were imprisoned in Upper Fort Garry.[6]

Provisional government

Hearing of the unrest, Ottawa sent three emissaries to the Red River, including HBC representative Donald Alexander Smith.[29] While they were en route, the Métis National Committee declared a provisional government on 8 December, with Riel becoming its president on 27 December.[20]

Meetings between Riel and the Ottawa delegation took place on 5 and 6 January 1870. When these proved fruitless, Smith chose to present his case in a public forum. After large meetings on 19 and 20 January, Riel suggested the formation of a new convention split evenly between Francophone and Anglophone settlers to consider Smith's proposals. On 7 February, a new list of rights was presented to the Ottawa delegation, and Smith and Riel agreed to send representatives to Ottawa to engage in direct negotiations on that basis.[6] The provisional government established by Louis Riel published its own newspaper titled New Nation and established the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia to pass laws.[30] The Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia was the first elected government at the Red River Settlement and functioned from 9 March to 24 June 1870. The assembly had 28 elected representatives, including a president, Louis Riel, an executive council (government cabinet), adjutant general (chief of military staff), chief justice and clerk.[31]

Thomas Scott's execution

Despite the progress on the political front, the Canadian party continued to plot against the provisional government. They attempted to recruit supporters to overthrow Riel. However, they suffered a setback on 17 February, when forty-eight men, including Boulton and Thomas Scott, were arrested near Fort Garry.[6]

Boulton was tried by a tribunal headed by Ambroise-Dydime Lépine and sentenced to death for his interference with the provisional government.[33][34] He was pardoned, but Scott interpreted this as weakness by the Métis, who he regarded with open contempt.[6] After Scott repeatedly quarreled with his guards, they insisted that he be tried for insubordination. At his court martial he was found guilty and was sentenced to death. Riel was repeatedly entreated to commute the sentence, but Riel responded, "I have done three good things since I have commenced: I have spared Boulton's life at your instance, I pardoned Gaddy, and now I shall shoot Scott."[35]

Scott was soon executed by a Métis firing squad on 4 March.[36] Riel's motivations have been the cause of much speculation, but his justification was that he felt it necessary to demonstrate to the Canadians that the Métis must be taken seriously. Protestant Canada did take notice, swore revenge, and set up a "Canada First" movement to mobilize their anger.[37][32] Riel biographer Lewis Thomas noted that "as people then and later have said, it was Riel's one great political blunder".[6]

Creation of Manitoba and the Wolseley expedition

The delegates representing the provisional government arrived in Ottawa in April. Although they initially met with legal difficulties arising from the execution of Scott, they soon entered into direct talks with Macdonald and George-Étienne Cartier. The parties agreed on several of the demands in the list of rights, including language, religious, and land rights (excepting ownership of public lands). This agreement formed the basis for the Manitoba Act, which formally admitted Manitoba into the Canadian confederation; the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia unanimously supported joining. However, the negotiators could not secure a general amnesty for the provisional government; Cartier held that this was a question for the British government.[6][38]

As a means of exercising Canadian authority in the settlement and dissuading American expansionists, a Canadian military expedition under Colonel Garnet Wolseley was dispatched to the Red River. Although the government described it as an "errand of peace", Riel learned that Canadian militia elements in the expedition meant to lynch him.[6]

Intervening years

Amnesty question

It was not until 2 September 1870 that the new Lieutenant-governor Adams George Archibald arrived and set about the establishment of civil government.[39] Without an amnesty, and with the Canadian militia threatening his life, Riel fled to the safety of the St. Joseph's mission across the Canada–US border in the Dakota Territory.[40] The results of the first provincial election in December 1870 were promising for Riel, as many of his supporters came to power. Nevertheless, stress and financial troubles precipitated a serious illness—perhaps a harbinger of his future mental afflictions—that prevented his return to Manitoba until May 1871.[6]

The settlement now faced a possible threat, from cross-border Fenian raids coordinated by his former associate William Bernard O'Donoghue.[41] Archibald issued a call to arms in October, and assured Riel that if he participated he would not be arrested. Riel organized several companies of Métis troops for the defense of Manitoba. When Archibald reviewed the troops in St. Boniface, he made the significant gesture of publicly shaking Riel's hand, signaling that a rapprochement had been effected.[42][41][6]

When this news reached Ontario, Mair and members of the Canada First movement whipped up anti-Riel (and anti-Archibald) sentiment. With Federal elections coming in 1872, Macdonald could ill afford further rift in Quebec–Ontario relations and so he did not offer an amnesty. Instead he quietly arranged for Taché to offer Riel a bribe of C$1,000 to remain in voluntary exile. This was supplemented by an additional £600 from Smith for the care of Riel's family.[43][6]

Nevertheless, by late June Riel was back in Manitoba and was soon persuaded to run as a member of parliament for the electoral district of Provencher. However, following the early September defeat of George-Étienne Cartier in his home riding in Quebec, Riel stood aside so that Cartier—on record as being in favour of amnesty for Riel—might secure a seat in Provencher. Cartier won by acclamation, but Riel's hopes for a swift resolution to the amnesty question were dashed following Cartier's death on 20 May 1873. In the ensuing by-election in October 1873, Riel ran unopposed as an Independent, although he had again fled, a warrant having been issued for his arrest in September. Lépine was not so lucky; he was captured and faced trial.[6][44]

Riel made his way to Montreal and, fearing arrest or assassination, vacillated as to whether he should attempt to take up his seat in the House of Commons—Edward Blake, the Premier of Ontario, had announced a bounty of $5,000 for his arrest.[45][6] Riel was the only Member of Parliament who was not present for the great Pacific Scandal debate of 1873 that led to the resignation of the Macdonald government in November. Liberal leader Alexander Mackenzie became the interim prime minister, and a general election was held in January 1874. Although the Liberals under Mackenzie formed the new government, Riel easily retained his seat. Formally, Riel had to sign a register book at least once upon being elected, and he did so under disguise in late January. He was nevertheless stricken from the rolls following a motion supported by Schultz, who had become the member for the electoral district of Lisgar. Riel prevailed again in the resulting by-election and was again expelled.[46][6][47]

Exile and mental illness

During this period, Riel had been staying with the Oblate fathers in Plattsburgh, New York, who introduced him to parish priest Fabien Martin dit Barnabé in the nearby village of Keeseville. It was here that he received news of Lépine's fate: following his trial for the murder of Scott, which had begun on 13 October 1874, Lépine was found guilty and sentenced to death. This sparked outrage in the sympathetic Quebec press, and calls for amnesty for both Lépine and Riel were renewed. This presented a severe political difficulty for Mackenzie, who was hopelessly caught between the demands of Quebec and Ontario. However, a solution was forthcoming when, acting on his own initiative, the Governor General Lord Dufferin commuted Lépine's sentence in January 1875. This opened the door for Mackenzie to secure from parliament an amnesty for Riel, on the condition that he remain in exile for five years.[15][6]

During his time of exile, Riel was primarily concerned with religion rather than politics. Much of these emerging religious beliefs were based on a supportive letter dated 14 July 1875 that he received from Montreal's Bishop Ignace Bourget. His mental state deteriorated, and following a violent outburst he was taken to Montreal, where he was under the care of his uncle, John Lee, for a few months. But after Riel disrupted a religious service, Lee arranged to have him committed in an asylum in Longue-Pointe on 6 March 1876 under the assumed name "Louis R. David".[15][6] Fearing discovery, his doctors soon transferred him to the Beauport Asylum near Quebec City under the name "Louis Larochelle".[48] While he suffered from sporadic irrational outbursts, he continued his religious writing, composing theological tracts with an admixture of Christian and Judaic ideas.[6] He consequently began calling himself "Louis David Riel, Prophet, Infallible Pontiff and Priest King".[49]

Nevertheless, he slowly recovered, and was released from the asylum on 23 January 1878 with an admonition to lead a quiet life. He returned for a time to Keeseville, where he became involved in a passionate romance with Evelina Martin dite Barnabé, sister of Father Fabien.[6] He asked her to marry him before moving west "with the avowed intention of establishing himself" before sending for her; however, their correspondence ended abruptly.[50]

Montana and family life

In the fall of 1878, Riel returned to St. Paul, and briefly visited his friends and family. This was a time of rapid change for the Métis of the Red River—the bison on which they depended were becoming increasingly scarce, the influx of settlers was ever-increasing, and much land was sold to unscrupulous land speculators. Like other Red River Métis who had left Manitoba, Riel headed further west to start a new life.[6] Travelling to the Montana Territory, he became a trader and interpreter in the area surrounding Fort Benton. Observing the detrimental impact of alcohol on the Métis, he engaged in an unsuccessful attempt to curtail the whisky trade.[6]

In Pointe-au-Loup, Fort Berthold, Dakota Territory in 1881,[51][52] he married the young Métis Marguerite Monet dite Bellehumeur,[6] according to the custom of the country (à la façon du pays), on 28 April, the marriage being solemnized on 9 March 1882.[12] Evelina learned of this marriage from a newspaper and wrote a letter accusing Riel of "infamy".[10][50] Marguerite and Louis were to have three children: Jean-Louis (1882–1908); Marie-Angélique (1883–1897); and a boy who was born and died on 21 October 1885, less than one month before Riel was hanged.[6]

Riel soon became involved in the politics of Montana, and in 1882, actively campaigned on behalf of the Republican Party. He brought a suit against a Democrat for rigging a vote, but was then himself accused of fraudulently inducing British subjects to take part in the election. In response, Riel applied for United States citizenship and was naturalized on 16 March 1883.[53] With two young children, he had by 1884 settled down and was teaching school at the St. Peter's Jesuit mission in the Sun River district of Montana.[6]

North-West Rebellion

Following the Red River Resistance, Métis travelled west and settled in the Saskatchewan Valley. But by the 1880s, the rapid collapse of the buffalo herd was causing near starvation among the First Nations. This was exacerbated by a reduction in government assistance, and by a general failure of Ottawa to live up to its treaty obligations. The Métis were likewise obliged to give up the hunt and take up agriculture—but this transition was accompanied by complex issues surrounding land claims similar to those that had previously arisen in Manitoba. Moreover, settlers from Europe and the eastern provinces were also moving into the Saskatchewan territories, and they too had complaints related to the administration of the territories. Virtually all parties therefore had grievances, and by 1884 Anglophone settlers, Anglo-Métis and Métis communities were holding meetings and petitioning a largely unresponsive government for redress.[54][55]

In the electoral district of Lorne, a meeting of the south branch Métis was held in the village of Batoche on 24 March, and representatives voted to ask Riel to return and represent their cause. On 6 May a joint "Settler's Union" meeting was attended by both the Métis and English-speaking representatives from Prince Albert, including William Henry Jackson, an Ontario settler sympathetic to the Métis and known to them as Honoré Jackson, and James Isbister of the Anglo-Métis.[56] It was here resolved to send a delegation to ask Riel to return.[55]

Return of Riel

The head of the delegation to Riel was Gabriel Dumont, a respected buffalo hunter and leader of the Saint-Laurent Métis who had known Riel in Manitoba.[57] James Isbister[58] was the lone Anglo-Métis delegate. Riel was easily swayed to support their cause. Riel also intended to use the new position of influence to pursue his own land claims in Manitoba.[6]

Upon his arrival Métis and Anglophone settlers alike formed an initially favourable impression of Riel following a series of speeches in which he advocated moderation and a reasoned approach. During June 1884, the Plains Cree leaders Big Bear and Poundmaker were independently formulating their complaints, and subsequently held meetings with Riel. However, the Native grievances were quite different from those of the settlers, and nothing was then resolved.[6]

Honoré Jackson and representatives of other communities set about drafting a petition to be sent to Ottawa. In the interim, Riel's support began to waver. As Riel's religious pronouncements became increasingly heretical the clergy distanced themselves, and father Alexis André cautioned Riel against mixing religion and politics. Also, in response to bribes by territorial lieutenant-governor and Indian commissioner Edgar Dewdney, local English-language newspapers adopted an editorial stance critical of Riel.[6]

Nevertheless, the work continued, and on 16 December Riel forwarded the committee's petition to the government, along with the suggestion that delegates be sent to Ottawa to engage in direct negotiation. Receipt of the petition was acknowledged by Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau, Macdonald's Secretary of State, although Macdonald himself would later deny having ever seen it.[6] By then many original followers had left; only 250 remained at Batoche when it fell in May 1885.[59]

While Riel awaited news from Ottawa he considered returning to Montana, but had by February resolved to stay. Without a productive course of action, Riel began to engage in obsessive prayer, and was experiencing a significant relapse of his mental agitations. This led to a deterioration in his relationship with the Catholic clergy, as he publicly espoused an increasingly heretical doctrine.[6]

On 11 February 1885, a response to the petition was received. The government proposed to take a census of the North-West Territories, and to form a commission to investigate grievances. This angered a faction of the Métis who saw it as a mere delaying tactic; they favoured taking up arms at once. Riel became the leader of this faction, but he lost the support of almost all Anglophones and Anglo-Métis, and the Catholic Church.[12] He also lost the support of the Métis faction supporting local leader Charles Nolin.[60] But Riel, undoubtedly influenced by his messianic delusions,[61] became increasingly supportive of this course of action. Disenchanted with the status quo, and swayed by Riel's charisma and eloquent rhetoric, hundreds of Métis remained loyal to Riel, despite his proclamations that Bishop Ignace Bourget should be accepted as pope, and that "Rome has fallen".[6][48]

Open rebellion

The Provisional Government of Saskatchewan was declared at Batoche on 19 March, with Riel as the political and spiritual leader and with Dumont assuming responsibility for military affairs.[55][62][6] Riel formed a council called the Exovedate (a neologism meaning "those who picked from the flock").[6] On 21 March, Riel's emissaries demanded that Crozier surrender Fort Carlton.[62] Scouting near Duck Lake on 26 March, a force led by Gabriel Dumont unexpectedly chanced upon a party from Fort Carlton. In the ensuing Battle of Duck Lake, the police were routed and the North-West Rebellion was begun in earnest.[62][12]

The near-completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway allowed troops from eastern Canada to quickly arrive in the territory.[63] Knowing that he could not defeat the Canadians in direct confrontation, Dumont had hoped to force the Canadians to negotiate by engaging in a long-drawn out campaign of guerrilla warfare; Dumont realized a modest success along these lines at the Battle of Fish Creek on 24 April 1885.[64] Riel, however, insisted on concentrating forces at Batoche to defend his "city of God".[6] The outcome of the ensuing Battle of Batoche which took place from 9 to 12 May[54] was never in doubt, and on 15 May a disheveled Riel surrendered to Canadian forces.[6] Although Big Bear's forces managed to hold out until the Battle of Loon Lake on 3 June,[65] the Rebellion was a dismal failure for Indigenous communities.[54]

Trial

_MIKAN_3192595.jpg.webp)

Several individuals closely tied to the government requested that the trial be held in Winnipeg in July 1885. Some historians contend that the trial was moved to Regina because of concerns with the possibility of an ethnically mixed and sympathetic jury.[66] Prime Minister Macdonald ordered the trial to be convened in Regina, where Riel was tried before a jury of six Anglophone Protestants. The trial began on 20 July 1885.[6]

Riel delivered two long speeches during his trial, defending his own actions and affirming the rights of the Métis people. He rejected his lawyers' attempt to argue that he was not guilty by reason of insanity. The jury found him guilty but recommended mercy; nonetheless, Judge Hugh Richardson sentenced him to death on 1 August 1885, with the date of his execution initially set for 18 September 1885.[6] "We tried Riel for treason," one juror later said, "And he was hanged for the murder of Scott."[67] Lewis Thomas notes that "the government's conduct of the case was to be a travesty of justice".[6]

Execution

Boulton writes in his memoirs that, as the date of his execution approached, Riel regretted his opposition to the defence of insanity and vainly attempted to provide evidence that he was not sane.[49][68] Requests for a retrial, petitions for a commuted sentence, and an appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Britain were denied.[6] John A. Macdonald, who was instrumental in upholding Riel's sentence, is famously quoted as saying "He shall hang though every dog in Quebec bark in his favour" (although the veracity of this quote is uncertain).[69]

Before his execution, Riel received Father André as his spiritual advisor. He was also given writing materials and allowed to correspond with friends and relatives.[70] Louis Riel was hanged for treason on 16 November 1885 at the North-West Mounted Police barracks in Regina.[71]

Boulton writes of Riel's final moments:

Père André, after explaining to Riel that the end was at hand, asked him if he was at peace with men. Riel answered "Yes." The next question was, "Do you forgive all your enemies?" "Yes." Riel then asked him if he might speak. Father André advised him not to do so. He then received the kiss of peace from both the priests, and Father André exclaimed in French, "Alors, allez au ciel!" meaning "So, go to heaven!"[72]

... [Riel's] last words were to say good-bye to Dr. Jukes and thank him for his kindness, and just before the white cap was pulled over his face he said, "Remerciez Madame Forget." meaning "Thank Mrs. Forget".[73]

The cap was pulled down, and while he was praying the trap was pulled. Death was not instantaneous. Louis Riel's pulse ceased four minutes after the trap-door fell and during that time the rope around his neck slowly strangled and choked him to death. The body was to have been interred inside the gallows' enclosure, and the grave was commenced, but an order came from the Lieutenant-Governor to hand the body over to Sheriff Chapleau which was accordingly done that night.[73]

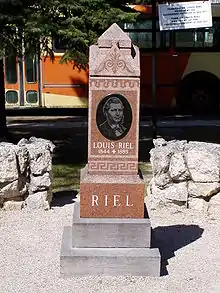

Following the execution, Riel's body was returned to his mother's home in St. Vital, where it lay in state. On 12 December 1886, his remains were interred in the churchyard of the Saint-Boniface Cathedral following the celebration of a requiem mass.[12]

The trial and execution of Riel caused a bitter and prolonged reaction which convulsed Canadian politics for decades. The execution was both supported and opposed by the provinces. For example, conservative Ontario strongly supported Riel's execution, but Quebec was vehemently opposed to it. Francophones were upset Riel was hanged because they thought his execution was a symbol of Anglophone dominance of Canada. The Orange Irish Protestant element in Ontario had demanded the execution as the punishment for Riel's treason and his execution of Thomas Scott in 1870. In Quebec, the politician Honoré Mercier rose to power by mobilizing the opposition in 1886.[15][74][75]

Historiography

Historians have debated the Riel case so often and so passionately that he is the most written-about person in Canadian history.[76] Interpretations have varied dramatically over time. The first amateur English language histories hailed the triumph of civilization, represented by English-speaking Protestants, over savagery represented by the half-breed Métis who were Catholic and spoke French. Riel was portrayed as an insane traitor and an obstacle to the expansion of Canada to the West.[77][78]

By the mid-20th century academic historians had dropped the theme of savagery versus civilization, deemphasized the Métis, and focused on Riel, presenting his execution as a major cause of the bitter division in Canada along ethnocultural and geographical lines of religion and language. W. L. Morton says of the execution that it "convulsed the course of national politics for the next decade": it was well received in Ontario, particularly among Orangemen, but francophone Quebec defended Riel as "the symbol, indeed as a hero of his race".[79] Morton concluded that some of Riel's positions were defensible, but that "they did not present a program of practical substance which the government might have granted without betrayal of its responsibilities".[80] J. M. Bumsted in 2000 said that for Manitoba historian James Jackson, the shooting of Scott—"perhaps the result of Riel's incipient madness—was the great blemish on Riel's achievement, depriving him of his proper role as the father of Manitoba."[81] The Catholic clergy had originally supported the Métis, but reversed themselves when they realized that Riel was leading a heretical movement. They made sure that he was not honored as a martyr.[82] However the clergy lost their influence during the Quiet Revolution, and activists in Quebec found in Riel the perfect hero, with the image now of a freedom fighter who stood up for his people against an oppressive government in the face of widespread racist bigotry. He was made a folk hero by Métis, French Canadian and other Canadian minorities. Activists who espoused violence embraced his image; in the 1960s, the Quebec terrorist group, the Front de libération du Québec adopted the name "Louis Riel" for one of its terrorist cells.[83]

Across Canada there emerged a new interpretation of reality in his rebellion, holding that the Métis had major unresolved grievances; that the government was indeed unresponsive; that Riel had chosen violence only as a last resort; and he was given a questionable trial, then executed by a vengeful government.[84] John Foster said in 1985 that "the interpretive drift of the last half-century ... has witnessed increasingly shrill though frequently uncritical condemnations of Canadian government culpability and equally uncritical identification with the "victimization" of the "innocent" Métis".[85] However, political scientist Thomas Flanagan reversed his views after editing Riel's writings: he argued that "the Métis grievances were at least partly of their own making", that Riel's violent approach was unnecessary given the government's response to his initial "constitutional agitation", and "that he received a surprisingly fair trial".[84]

An article by Doug Owram appearing in the Canadian Historical Review in 1982 found that Riel had become "a Canadian folk hero", even "mythical", in English Canada, corresponding with the designation of Batoche as a national historic site and the compilation of his writings.[86] That compilation consisted of three volumes of letters, diaries, and other prose writings; a fourth volume of his poetry; and a fifth volume which contained reference materials.[87] Edited by George Stanley, Raymond Huel, Gilles Martel, Thomas Flanagan and Glen Campbell, this work "ma[de] it possible to think comprehensively about Riel's life and his achievements", but was also criticized for some of its editorial decisions.[88] In a 2010 speech, Beverley McLachlin, then Chief Justice of Canada, summed up Riel as being a rebel by the standards of the time but a patriot "viewed through our modern lens".[89]

Legacy

The Saskatchewan Métis' requested land grants were all provided by the government by the end of 1887,[90] and the government resurveyed the Métis river lots in accordance with their wishes.[91] However, much of the land was soon bought by speculators who later turned huge profits from it.[92] Riel's worst fears were realized—following the failed rebellion, the French language and Roman Catholic religion faced increasing marginalization in both Saskatchewan and Manitoba, as exemplified by the controversy surrounding the Manitoba Schools Question.[93] The Métis themselves were increasingly forced to live in shantytowns on undesirable land.[94] Saskatchewan did not become a province until 1905.[95]

Riel's execution and Macdonald's refusal to commute his sentence caused lasting discord in Quebec. Honoré Mercier exploited the discontent to reconstitute the Parti National. This party, which promoted Quebec nationalism, won a majority in the 1886 Quebec election.[96][97] The federal election of 1887 likewise saw significant gains by the federal Liberals. This led to the victory of the Liberal party under Wilfrid Laurier in the federal election of 1896, which in turn set the stage for the domination of Canadian federal politics (particularly in Quebec) by the Liberal party in the 20th century.[98][6]

Since the 1980s, numerous federal politicians have introduced private member's bills seeking to pardon Riel or recognize him as a Father of Confederation.[99] In 1992, the House of Commons passed a resolution recognizing "the unique and historic role of Louis Riel as a founder of Manitoba and his contribution in the development of Confederation".[100][99] The CBC's Greatest Canadian project ranked Riel as the 11th "Greatest Canadian" on the basis of a public vote.[101]

Commemorations

In 2007, Manitoba's provincial government voted to recognize Louis Riel Day as a provincial holiday, observed on the third Monday of February.[102][103]

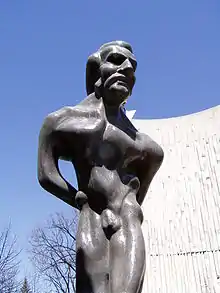

Two statues of Riel are located in Winnipeg. One of these statues, the work of architect Étienne Gaboury and sculptor Marcien Lemay, depicts Riel as a naked and tortured figure. It was unveiled in 1971 and stood in the grounds of the Manitoba Legislative Building for 23 years. After much outcry (especially from the Métis community) that the statue was an undignified misrepresentation, the statue was removed and placed at the Université de Saint-Boniface.[104][105] It was replaced with a statue of Louis Riel designed by Miguel Joyal depicting Riel as a dignified statesman. The unveiling ceremony was on 12 May 1996, in Winnipeg.[106][105] A statue of Riel on the grounds of the Saskatchewan Legislative Building in Regina was installed and later removed for similar reasons.[107]

In numerous communities across Canada, Riel is commemorated in the names of streets, schools, neighbourhoods, and other buildings. Examples in Winnipeg include the landmark Esplanade Riel pedestrian bridge linking old Saint-Boniface with Downtown Winnipeg,[108] and the Louis Riel School Division.[109] The student centre at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon is named after Riel, as is the Louis Riel Trail.[110] There are schools named after Louis Riel in four major Canadian cities: Calgary, Montreal, Ottawa and Winnipeg.[111][112][113][114]

Portrayals of Riel's role in the Red River Resistance include the 1979 CBC television film Riel[115] and Canadian cartoonist Chester Brown's acclaimed 2003 graphic novel Louis Riel: A Comic-Strip Biography.[116] An opera about Riel entitled Louis Riel was commissioned for Canada's centennial celebrations in 1967; it was written by Harry Somers, with an English and French libretto by Mavor Moore and Jacques Languirand.[117]

See also

Footnotes

- Bumsted 1992, pp. xiii, 31

- Bumsted, J. M. (1987). "The 'Mahdi' of Western Canada: Lewis Riel and His Papers". The Beaver. 67 (4): 47–54.

- Bumsted, J. M.; Smyth, Julie (25 March 2015). "Red River Colony". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Hamon 2019, p. 32

- Payment, Diane (1980). Riel Family: Home and Lifestyle at St-Vital, 1860–1910 (PDF) (Report). Parks Canada. p. 32. Report No. 379.

- Thomas, Lewis H. (2016) [1982]. "Riel, Louis (1844–85)". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 11.

- Morton, W. L. (1976). "Riel, Louis (1817–64)". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 9.

- Stanley 1963, pp. 13–20

- Hamon 2019, p. 30

- Mitchell, W.O. (1 February 1952). "The Riddle of Louis Riel Part 1". Maclean's.

- Goldsborough, Gordon (16 February 2020). "Louis 'David' Riel (1844–1885)". Memorable Manitobans. Manitoba Historical Society.

- "Louis Riel – One Life, One Vision" (PDF). Société historique de Saint-Boniface / Centre du patrimoine. 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Stanley 1963, pp. 26–28

- Markson, ER (1965). "The Life and Death of Louis Riel a Study in Forensic Psychiatry Part 1 – A Psychoanalytic Commentary". Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal. 10 (4): 246–252. doi:10.1177/070674376501000404. PMID 14341671.

- Stanley, George F. G.; Gaudry, Adam (9 May 2016). "Louis Riel". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Stanley 1963, p. 33

- "Louis Riel". Métis Nation of Ontario. 2006. Archived from the original on 7 July 2007.

- Stanley et al. 1985, pp. xxv & xxvi, Stanley's Foreword: "The Fréchette experience [in Chicago] is, however, open to question."

- Stanley 1963, pp. 13–34

- Bumsted, J. M.; Foot, Richard (22 November 2019). "Red River Rebellion". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Dorge, Lionel (1969). "Bishop Taché and the Confederation of Manitoba, 1969–1970". MHS Transactions. 3 (26).

- Brodbeck, Tom (13 December 2019). "The Riel deal". Winnipeg Free Press.

- Read, Colin (1982). "The Red River Rebellion and J. S. Dennis, 'Lieutenant and Conservator of the Peace'". Manitoba History (3).

- Read, Colin (1982). "Dennis, John Stoughton (1820–1885)". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 11.

- "Red River Resistance". Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- "Louis Riel". From Sea to Sea. CBC. 2001. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- "The Execution of Thomas Scott". From Sea to Sea. CBC. 2001. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Mitchell, Ross (1960). "John Christian Schultz, M.D. – 1840–1896". Manitoba Pageant. 5 (2).

- Reford, Alexander (1998). "Smith, Donald Alexander, 1st Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 14.

- "Local Laws". New Nation. Vol. 1, no. 18. 15 April 1870. p. 3.

- "Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia". Indigenous & Northern Relations. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- Dick, Lyle (2004–2005). "Nationalism and Visual Media in Canada: The Case of Thomas Scott's Execution". Manitoba History. 48 (Autumn/Winter): 2–18.

- Salhany 2020, p. 25

- Bélanger, Claude (2007). "The 'Murder' of Thomas Scott". The Quebec History Encyclopedia. Marianopolis College.

- Boulton 1985, p. 51

- Bumsted 2000, p. 3

- Anastakis 2015, p. 27

- Berger, Thomas (2015). "The Manitoba Metis Decision and the Uses of History". Manitoba Law Journal. 38 (1): 1–28.

- Bowles, Richard S. (1968). "Adams George Archibald, First Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba". MHS Transactions. 3 (25).

- Huel 2003, p. 117

- Swan, Ruth; Jerome, Edward A. (2000). "'Unequal justice:' The Metis in O'Donoghue's Raid of 1871". Manitoba History (39 Spring / Summer).

- Brodbeck, Tom (10 July 2020). "Métis stepped up for Crown, got stepped on for their trouble". Winnipeg Free Press.

- Gwyn 2011, pp. 150–151

- "Relations with First Nations and Métis". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- "Louis Riel (1844–1885): Biography" (PDF). Virtual Museum. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- Marleau, Robert; Montpetit, Camille (2000). "The House of Commons and Its Members – Notes 351–373". House of Commons Procedure and Practice. Parliament of Canada.

- Tolton 2011, p. 19

- "Rethinking Riel – Was Louis Riel Mentally Ill?". CBC. 2006.

- Littmann, S.K. (1978). "A Pathography of Louis Riel". Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal. 23 (7): 449–462. doi:10.1177/070674377802300706. PMID 361196.

- Campbell, Glen; Flanagan, Tom (Fall 2019). "Louis Riel's romantic interests". Manitoba History (90): 2–12.

- "L'arbre généalogique de Louis Riel" (PDF). Société historique de Saint-Boniface / Centre du patrimoine. 2020.

- Payment, Diane (1980). Riel Family: Home and Lifestyle at St-Vital, 1860–1910 (PDF) (Report). Parks Canada, Historical Research Division, Prairie Region. Manuscript Report Number 379. Map of Figure 10 points east of mouth of Rivière au Lait & Missouri River towards Ft. Berthold, Dakota Territory and/or Pointe au Loup.

- "Louis Riel (October 22, 1844 – November 16, 1885)". Library and Archives Canada. Archived from the original on 4 May 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- Beal, Bob; MacLeod, Rod; Foot, Richard (30 July 2019). "North-West Rebellion". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- "1885 Northwest Resistance". Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- Flanagan, Thomas (1991). "Louis Riel's Land Claims". Manitoba History. 21 (Spring).

- Gaudry, Adam (9 September 2019). "Gabriel Dumont". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Smyth, David (1998). "Isbister, James". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 14.

- Miller 2004, p. 44

- Payment, Diane P. (1994). "Nolin, Charles". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 13.

- Dumontet, Monique (1994). "Essay 16 Controversy in the Commemoration of Louis Riel". Mnemographia Canadensis. 2.

- Ouellette, Robert-Falcon (Autumn 2014). "The Second Métis War of 1885: A Case Study of Non-Commissioned Member Training and the Intermediate Leadership Program" (PDF). Canadian Military Journal. 14 (4): 54–65.

- Foster, Keith; Oosterom, Nelle (13 February 2014). "Shifting Riel-ity: The 1885 North-West Rebellion". Canada's History.

- "The Battle of Fish Creek (April 23, 1885)" (PDF). Virtual Museum. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- Mein, Stewart (2006). "North-West Resistance". The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan.

- Basson 2008, p. 66

- Stanley 1979, p. 23

- Boulton 1886, p. 411

- Gwyn 2011, p. 469

- Mitchell, W.O. (15 February 1952). "The Riddle of Louis Riel: Conclusion". Maclean's.

- "Louis Riel (October 22, 1844 – November 16, 1885)". Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- Boulton 1886, p. 413

- Boulton 1886, p. 414

- Stewart 2002, p. 156

- Read, Geoff; Webb, Todd (2012). "'The Catholic Mahdi of the North West': Louis Riel and the Metis Resistance in Transatlantic and Imperial Context". Canadian Historical Review. 93 (2): 171–195. doi:10.3138/chr.93.2.171.

- Hamon 2019, p. 14

- Francis, Jones & Smith 2009, pp. 306–307

- Sprague 1988, p. 1

- Morton 1963, p. 371

- Morton 1963, p. 369

- Bumsted 2000, p. 17

- Perin 1990, p. 259

- Saywell 1973, p. 94

- Flanagan 2000, p. x

- Foster, John E. (1985). "Review of Riel and the Rebellion 1885 Reconsidered By Thomas Flanagan". Great Plains Quarterly. 5 (4): 259–260.

- Owram, Douglas (1982). "The Myth of Louis Riel". The Canadian Historical Review. 63 (3): 315–336. doi:10.3138/CHR-063-03-01.

- Stanley et al. 1985

- Hamon 2019, p. 15

- McLachlin, Beverley (2011). "Louis Riel: Patriot Rebel" (PDF). Manitoba Law Journal. 35 (1): 1–13.

- Flanagan 2000, p. 82

- Flanagan 2000, p. 60

- Robinson, Amanda (6 November 2018). "Métis Scrip in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Godbout 2020, pp. 151–154

- "1885 – Aftermath". Our Legacy. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Tattrie, Jon (3 February 2015). "Saskatchewan and Confederation". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Godbout 2020, p. 152

- "Parti national". The Canadian Encyclopedia. 19 February 2014.

- Godbout 2020, p. 153

- Reid 2008, p. 4.

- Flanagan 2000, p. 179

- "And the Greatest Canadian of all time is..." CBC. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- Reid 2008, p. 5.

- "Louis Riel Day holiday (3rd Mon. in Feb.)". Government of Manitoba. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- "Louis Riel Statue". Winnipeg Architecture Foundation. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Bower, Shannon (2001). ""Practical Results": The Riel Statue Controversy at the Manitoba Legislative Building". Manitoba History. 42 (Autumn / Winter 2001–2002).

- "Private Members' Business regarding An Act to Revoke the Conviction of Louis David Riel – Bill C297". Hansard Debates for Friday, November 22, 1996. House Publications Parliament of Canada. 1996.

- Beatty, Greg (Winter 2003–2004). "Kim Morgan: Antsee" (PDF). Espace Sculpture (66): 42.

- "Winnipeg's Esplanade Riel: A magnificent bridge connecting people and cultures". Le Corridor. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- "Our history: a look back". Louis Riel School Division. 18 August 2014.

- "Place Riel opens". University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- "Louis Riel School". Calgary Board of Education. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- "École secondaire Louis-Riel". Ministère de l'Éducation et de l'Enseignement supérieur. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- "École secondaire publique Louis-Riel". Conseil des écoles publiques de l'Est de l'Ontario. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- "Notre histoire". Division scolaire franco-manitobaine. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- Walz, Eugene; Payment, Diane; Laroque, Emma (1981). "Review: Three Views of Riel". Manitoba History (1).

- Bell 2006, p. 166

- King, Betty; Winters, Kenneth (20 April 2017). "Louis Riel (opera)". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

References

- Anastakis, Dimitry (2015). Death in the Peaceable Kingdom: Canadian History since 1867 through Murder, Execution, Assassination, and Suicide. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1442606364.

- Basson, Lauren L. (2008). White enough to be American?. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5837-0.

- Bell, John (2006). Invaders from the North: How Canada Conquered the Comic Book Universe. Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-659-7.

- Boulton, Charles Arkoll (1886). Reminiscences of the North-West Rebellions. Grip Printing & Publishing Co.

- Boulton, Charles Arkoll (1985). Robertson, Heather (ed.). I Fought Riel. James Lorimer & Company. ISBN 0-88862-935-4.

- Bumsted, J. M. (1992). The Peoples of Canada: A Post-Confederation History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-540914-0.

- Bumsted, J. M. (2000). Thomas Scott's Body: And Other Essays on Early Manitoba History. University of Manitoba Press. ISBN 978-0887553875.

- Flanagan, Thomas (2000). Riel and the Rebellion: 1885 Reconsidered (2nd ed.). University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802082823.

- Francis, R. Douglas; Jones, Richard; Smith, Donald B., eds. (2009). Journeys: A History of Canada. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0176442446.

- Godbout, Jean-François (2020). Lost on Division: Party Unity in the Canadian Parliament. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1487535421.

- Gwyn, Richard J. (2011). Nation Maker: Sir John A. Macdonald: His Life, Our Times. Life and Times of Sir John A. Macdonald Series. Vol. 2. Random House Canada. ISBN 978-0307356444.

- Hamon, Max (2019). The Audacity of His Enterprise: Louis Riel and the Métis Nation That Canada Never Was, 1840–1875. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0773559370.

- Huel, R.J.A. (2003). Archbishop A.-A. Taché of St. Boniface: The "Good Fight" and the Illusive Vision. Missionary Oblates Mary Immaculate. University of Alberta Press. ISBN 978-0-88864-406-0.

- Miller, James Rodger (2004). Reflections on Native-newcomer Relations: Selected Essays (2nd ed.). University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-8669-1.

- Morton, William Lewis (1963). The Kingdom of Canada: A General History from Earliest Times. McClelland and Stewart.

- Reid, Jennifer (2008). Louis Riel and the Creation of Modern Canada: Mythic Discourse and the Postcolonial State. University of Manitoba Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-4415-1. OCLC 1037748071.

- Perin, Roberto (1990). Rome in Canada: The Vatican and Canadian Affairs in the Late Victorian Age. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0802067623. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt2tv08x.

- Salhany, Roger (2020). A Rush to Judgment: The Unfair Trial of Louis Riel. Dundurn. ISBN 978-1459746107.

- Saywell, John T., ed. (1973). Canadian Annual Review of Politics and Public Affairs: 1971. University of Toronto Press. doi:10.3138/9781442671850. ISBN 978-1442671850.

- Sprague, D.N. (1988). Canada and the Métis, 1869–1885. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-958-8.

- Stanley, George (1963). Louis Riel. McGraw-Hill Ryerson. ISBN 0-07-092961-0.

- Stanley, George F.G. (1979) [1964]. Louis Riel: Patriot or Rebel? (PDF). The Canadian Historical Association Booklets, 2 (8th ed.). Canadian Historical Association. ISBN 0-88798-003-1.

- Stanley, George; Huel, Raymond; Martel, Gilles; Flanagan, Thomas; Campbell, Glen, eds. (1985). The Collected Writings of Louis Riel/Les Ecrits Complets de Louis Riel. University of Alberta Press. ISBN 0-88864-091-9.

- Stewart, Roderick (2002). Wilfrid Laurier. Dundurn. ISBN 978-1770707559.

- Tolton, Gordon Errett (2011). Cowboy Cavalry: The Story of the Rocky Mountain Rangers. Heritage House Publishing. ISBN 978-1926936024.

Further reading

- Barkwell, Lawrence J.; Dorion, Leah; Prefontaine, Darren (2001). Metis Legacy: A Historiography and Annotated Bibliography. Pemmican Publications Inc. / Gabriel Dumont Institute. ISBN 1-894717-03-1.

- Braz, Albert (2003). The False Traitor: Louis Riel in Canadian Culture. University of Toronto Press.

- Flanagan, Thomas (1979). Louis 'David' Riel: prophet of the new world. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-88780-118-8.

- Flanagan, Thomas (1983). Riel and the Rebellion. Western Producer Prairie Books. ISBN 0-88833-108-8.

- Flanagan, Thomas (1992). Louis Riel. Canadian Historical Association. ISBN 0-88798-180-1.

- Hansen, Hans (2014). Riel's Defence: Perspectives on His Speeches (1st ed.). McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0773543362.

- Kinsey, Howard Joseph (1952). Strange Empire: A Narrative of the Northwest (Louis Riel and the Metis People). William Morrow & Co. ISBN 0-87351-298-7.

- Knox, Olive (1949–1950). "The Question of Louis Riel's Insanity". MHS Transactions. 3 (6).

- Siggins, Maggie (1994). Riel: a life of revolution. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-215792-6.

- Stanley, G. F. G. (1964). "Louis Riel". Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française. 18 (1): 14–26. doi:10.7202/302338ar.

- Woodcock, George (March 1959). "Louis Riel: Defender of the Past". History Today. 9 (3): 198–207.