Louis Vivet

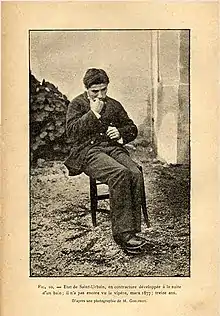

Louis Vivet (also Louis Vivé or Vive; born 12 February 1863) was one of the first mental health patients to be diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder, colloquially known as "multiple [or] split personalities."[1] Within one year of his 1885 diagnosis, the term "multiple personality" appeared in psychological literature in direct reference to Vivet.[2]

Early life and first symptoms

Vivet was born on 12 February 1863, in Paris to a young mother who worked as a prostitute and who beat and neglected him.[3] After turning to crime at age eight, Vivet was sent to a house of corrections, where he was raised until the age of 18.[4] While working on a farm at age 17, Vivet became paralyzed from the waist down due to severe trauma resulting from a viper wrapping itself around his hand, inducing psychosomatic paralysis.[4] Vivet went on to work as a tailor during his paralysis, until one-and-a-half years later, when he suddenly regained the use of his legs and began walking.[4] When confronted by the asylum (which had begun housing him upon his paralysis) regarding his newfound ability to walk, Vivet responded with confusion, not recognizing any of the hospital staff and accusing them of imprisoning him.[4]

Diagnosis and identities

Diagnosis and treatment

Although Vivet was purported to have up to ten personalities, recent re-evaluations of the medical literature have led some psychologists to believe that he had only two personalities, and that any other personalities were the direct result of hypnosis by therapists.[5] Vivet's symptoms, including loss of time and amnesia, were explained by the first psychologist to treat him, Camuset, as divisions in his personality, and were not directly linked to his history of childhood trauma until his case was re-evaluated approximately 100 years later.[6] Some experts believe that Vivet did not have DID at all, and that his behavior was similar to that of a fugue state.[7]

Philosopher Ian Hacking has argued that the term "multiple personality disorder" first came into use on 25 July 1885, when Vivet entered the health system and became the subject of intensive psychiatric experimentation.[8] He was subjected to a variety of treatments for what doctors initially believed to be "hysteria," including "morphines, injections of pilocarpine, oil of ipecac to induce vomiting, and magnets on numerous parts of the body; but the only treatment that could halt an attack was pressure on the achilles tendon or the rotulian tendon below the kneecap...he was repeatedly hypnotized."[9]

Dissociative identity system

The return of Vivet's motor skills was accompanied by a stark change in personality: when paralyzed, Vivet was kind, reserved, intellectual, and meek, while in his walking state, he was arrogant, confrontational, and conniving.[10] Vivet's memories were segregated entirely between his different personalities. He had no recollection of his actions conducted as his various personalities...he could only recall the memories of his current personality, except any memories pre-dating the traumatic viper incident.[10]

Psychologist Pierre Janet described Vivet as having six "existences." He continues:

These alternated and involved both dissociation and retraction of the field of consciousness: Each had different memories, personal characteristics, and varying degrees of sensory and movement problems. for example, one was gentle and hardworking; another lazy and irritable; another was incoherent with paralysis on the left side; and one had paraplegia (paralysis of the lower body).[11]

In popular culture

It is claimed that Robert Louis Stevenson was influenced by Vivet's story while writing the novella Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.[12] However, Stevenson was not aware of Vivet's story while writing Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, as it was published a few months before Vivet's case was published.[13]

See also

References

- Faure, Henri; Kersten, John (June 1997). "The 19th Century DID Case of Louis Vivet: New Findings and Re-evaluation" (PDF). Dissociation. X (2): 104.

- Kubiak, Anthony (2002). Agitated States: Performance in the American Theater of Cruelty. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 169. ISBN 0472068113.

- Hacking, Ian (1998). Rewriting the Soul: Multiple Personalities and the Science of Memory. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 174. ISBN 1400821681.

- Faure, Henri; Kersten, John (June 1997). "The 19th Century DID Case of Louis Vivet: New Findings and Re-evaluation" (PDF). Dissociation. X (2): 105.

- Faure, Henri; Kersten, John (June 1997). "The 19th Century DID Case of Louis Vivet: New Findings and Re-evaluation" (PDF). Dissociation. X (2): 108.

- Vermetten, Eric; Dorahy, Martin; Spiegel, David (2007). Traumatic Dissociation: Neurobiology and Treatment. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 13. ISBN 9781585627141.

- Hacking, Ian (2002). Mad Travelers: Reflections on the Reality of Transient Mental Illnesses. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 120. ISBN 0674009541.

- Lockhurst, Roger (June 2013). The Trauma Question. Routledge. p. 40. ISBN 978-1136015021.

- Hacking, Ian (1998). Rewriting the Soul: Multiple Personalities and the Science of Memory. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 177. ISBN 1400821681.

- Faure, Henri; Kersten, John (June 1997). "The 19th Century DID Case of Louis Vivet: New Findings and Re-evaluation" (PDF). Dissociation. X (2): 106.

- Reyes, Gilbert (2008). The Encyclopedia of Psychological Trauma (Google eBook). John Wiley & Sons. p. 423. ISBN 978-0470447482.

- Davis, Colin (Spring 2012). "From psychopathology to diabolical evil: Dr Jekyll, Mr Hyde and Jean Renoir". Journal of Romance Studies. 12 (1): 10. doi:10.3828/jrs.12.1.10.

- "Identity Crisis, 1906". The Scientist Magazine®. Retrieved 28 November 2022.