Louise of Orléans

Louise of Orléans (Louise-Marie Thérèse Charlotte Isabelle; 3 April 1812 – 11 October 1850) was the first Queen consort of the Belgians as the second wife of King Leopold I from their marriage on 9 August 1832 until her death in 1850. She was the second child and eldest daughter of the French king Louis Philippe I and his wife, Maria Amalia of the Two Sicilies. Louise rarely participated in public representation, but acted as the political adviser of her spouse. Her large correspondence is a valuable historical source of the period and has been published.

| Louise of Orléans | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_by_Winterhalter%252C_1841.jpg.webp) Portrait by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1841 | |||||

| Queen consort of the Belgians | |||||

| Tenure | 9 August 1832 – 11 October 1850 | ||||

| Born | 3 April 1812 Palermo, Kingdom of Sicily | ||||

| Died | 11 October 1850 (aged 38) Ostend, Kingdom of Belgium | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| House | Orléans | ||||

| Father | Louis Philippe I of France | ||||

| Mother | Maria Amalia of the Two Sicilies | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Life

Born in Palermo, Sicily, on 3 April 1812, she was the eldest daughter of the future Louis-Philippe I, King of the French, and of his wife Maria Amalia of the Two Sicilies. As a child, she had a religious and bourgeoisie education thanks to the part played by her mother and her aunt, Princess Adélaïde of Orléans, to whom she was very close. She was given a strict religious upbringing by her aunt. She also learned to speak English, German, Dutch and Italian.

As a member of the reigning House of Orléans, she was entitled to the rank of a Princess of the Blood Royal.

Marriage

In 1830, her father became King of the French. Her position thus changed and her status was raised to that of the eldest daughter of a king.

On 9 August 1832, the twenty-year-old Louise married King Leopold I of the Belgians, who was twenty-two years her senior, at the Compiègne Palace. Leopold had been widowed after the death of his first wife, Princess Charlotte of Wales, in childbirth in 1817. Since Leopold was a Protestant, he and Louise had both a Catholic and a Calvinist ceremony.

The marriage had been suggested already when Leopold was considered for the throne of Greece, and was repeated when he was elected king of the Belgians instead of Louise's brother the duke of Nemours. The marriage created an alliance between two newly elected and less established monarchs, her father and spouse, and was thus seen suitable. Louise's mother disliked the marriage because Leopold was a Protestant, but since Louise's father was a new monarch and his position weak in the eyes of other monarchs, the marriage was considered favorable for the new French Orléans dynasty, as it might then become easier for Louise's siblings to marry members of established dynasties.

While the marriage was arranged against Louise's will, and she was unhappy to leave France and her family, Leopold was very careful to treat her with consideration and respect from the beginning, which was appreciated by Louise, and soon their relationship came to be described as a harmonious one. Described as a devoted wife and loving mother, she was of a shy nature, and as her husband prefer for her to live a quiet family life, she was not given much opportunity to overcome her shyness. She lived a private family life devoted to the upbringing of her children, and it was noted how she entertained Leopold by reading for him from Stendhal, Chateaubriand, Byron and Shakespeare.

After the birth of their last child in 1840, Leopold and Louise often spent their free time separately: while Leopold visited the Ardennes, Louise preferred to take her vacations in Oostende. From 1844, Leopold had a relationship with Arcadie Claret, whom he settled in a house near the palace in Brussels. Louise's health, which was weakened by childbirth as well as the misfortunes of her family in France, caused the sympathies of the public to be with Louise against Leopold in this matter, and the carriage of his mistress was bombarded with filth on the street.

Public role as Queen

Queen Louise was described as a shy and introverted personality with weak health. Belgium was a newly independent monarchy, and there was yet no established tradition about what the role of a queen consort should look like. King Leopold's view was that public royal representation was to be used sparsely, and he did not create a public role for Louise as queen. Queen Louise was rarely seen in public and her life centered around the supervision of her children's upbringing, correspondence with her birth family in France, and religious devotion with her private confessor Pierre de Coninck, with whom she had a close relationship. Louise was given four ladies-in-waiting as companions: the Dame d'honneur, Countess Louise-Jeanne de Thezan du Poujol de Merode, and the three Dames du Palais, Baroness Caroline du Mas Goswin de Stassart, Baroness Caroline de Wal Masbourg Emmanuel d'Hooghvorst, and Countess Zoé Vilain.

While the king seldom engaged himself and even more rarely Louise in public representation, he did however regularly arrange private royal representation in the form of receptions, balls and state banquets for the aristocracy in the royal Palace of Laeken. During the first years of his reign, most of the guests were British, as the Belgian nobility were still largely loyal to the House of Orange, but gradually the Belgian aristocracy started to attend the royal receptions. The guests of the royal receptions were almost the only people Louise met in Belgium. Among this small circle, Louise gradually became somewhat less shy and appeared to enjoy the masquerade balls.

Every morning, Queen Louise received reports from her ladies-in-waiting of people asking her for financial assistance. She then personally visited their homes to bring them comfort and financial aid. Sometimes Queen Louise did not have enough money for her charitable works and then borrowed money from her ladies-in-waiting without telling her husband. She also received such applications from France and often answered them if her secretary informed her that they were genuine. She was a supporter of the lace making business, which was in a period of decline in the 1830s but was greatly helped by her financial support of a lace making school.

King Leopold eventually allowed Louise to make her own trips around Belgium, and her favorite place became the Flemish coastal towns, particularly Oostende, where she took riding trips, bathed in the sea and walked along the beach, collecting seashells. She was seldom permitted to make trips abroad. Leopold did not bring her on his visit to the baptism of Princess Victoria in London in 1841, despite her wish to accompany him. He did bring her to Paris to visit her parents in 1841, as well as to Brühl in 1843, where she met Queen Victoria of Great Britain. In 1844, she celebrated her birthday with Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace, and she was also present at the state visit to London in 1847.

Despite the fact that Queen Louise was a shy personality who was rarely seen in public, she was a person with a strong will and many opinions in private. She was known to have a great interest in political issues, and the contemporary German press once claimed that the Belgian queen "has an extreme interest in political affairs and this is an issue of discontent in Brussels".[1] King Leopold did in fact, with time, ask for her opinions in state affairs, and she is known to have given him advice in diplomatic issues.[2] Eventually, the king's confidence in her ability grew to an extent that he suggested to the government that Queen Louise should be made official regent when he was absent from the country. [3] His suggestion was however met with such unanimous opposition that he was forced to retract his plans. [4]

Queen Louise was given public sympathy in Belgium when her parents were deposed during the February Revolution of 1848. She visited her exiled parents in England in October that same year. The revolution in France made the Belgian king and queen more popular in Belgium, and they toured the Belgian provinces to great acclaim.

Death

Queen Louise died of tuberculosis in the former Royal palace of Ostend on 11 October 1850.[5] Her death was confirmed in record by ministers Charles Rogier and Victor Tesch. Her body was brought to Laeken, and a memorial was erected in Oostende. She is buried beside her husband in the Royal Crypt of the Church of Our Lady of Laeken.

Children

Louise and Leopold had four children, including Leopold II of Belgium and Empress Carlota of Mexico.

- Prince Louis Philippe, Crown Prince of Belgium (24 July 1833 – 16 May 1834)

- King Leopold II of the Belgians (9 April 1835 – 17 December 1909)

- Prince Philippe, Count of Flanders (24 March 1837 – 17 November 1905)

- His son succeeded Leopold II as King Albert I of the Belgians;

- Princess Charlotte of Belgium (7 June 1840 – 19 January 1927), consort of Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico.

Honours

.svg.png.webp) Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Royal Order of Leopold

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Royal Order of Leopold.svg.png.webp) Portugal: Dame of the Order of Queen Saint Isabel, 14 July 1835[6]

Portugal: Dame of the Order of Queen Saint Isabel, 14 July 1835[6].svg.png.webp) Spain: Dame of the Order of Queen Maria Luisa, 10 February 1835[7]

Spain: Dame of the Order of Queen Maria Luisa, 10 February 1835[7]

Arms

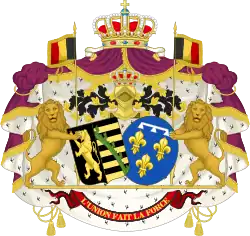

Alliance Coat of Arms of King Leopold I

Alliance Coat of Arms of King Leopold I

and Queen Louise Royal Monogram of Queen Louise-Marie

Royal Monogram of Queen Louise-Marie

of Belgium

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Louise of Orléans | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Hippolyte d'Ursel, Lettres intimes de Louise d'Orléans : Première reine des Belges, Paris, Éditions Jourdan, 2015, 286 p. (ISBN 978-2-930757-48-3)

- Georges van den Abeelen, Portraits de rois : 150 ans de monarchie constitutionnelle, Bruxelles, 1981, p. 44.

- Carlo Bronne, Léopold Ier et son Temps, Bruxelles, Goemaere, 1947, 399 p., p. 163.

- Carlo Bronne, Léopold Ier et son Temps, Bruxelles, Goemaere, 1947, 399 p., p. 163.

- King Leopold I, Monarchie.be, Retrieved 2 April 2016

- Bragança, Jose Vicente de (2014). "Agraciamentos Portugueses Aos Príncipes da Casa Saxe-Coburgo-Gota" [Portuguese Honours awarded to Princes of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha]. Pro Phalaris (in Portuguese). 9–10: 5. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Real orden de damas nobles de la Reina Maria Luisa", Calendario Manual y Guía de Forasteros en Madrid (in Spanish): 91, 1848, retrieved 20 April 2020