African wild dog

The African wild dog (Lycaon pictus), also known as the painted dog or Cape hunting dog, is a wild canine native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is the largest wild canine in Africa, and the only extant member of the genus Lycaon, which is distinguished from Canis by dentition highly specialised for a hypercarnivorous diet, and by a lack of dewclaws. It's estimated that there are around 6,600 adults (including 1,400 mature individuals) living in 39 subpopulations that are all threatened by habitat fragmentation, human persecution, and outbreaks of disease. As the largest subpopulation probably comprises fewer than 250 individuals, the African wild dog has been listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List since 1990.[2]

| African wild dog | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| At Tswalu Kalahari Reserve, South Africa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Subfamily: | Caninae |

| Tribe: | Canini |

| Genus: | Lycaon |

| Species: | L. pictus |

| Binomial name | |

| Lycaon pictus | |

| |

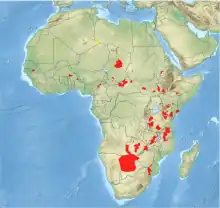

| African wild dog range according to the IUCN.

Extant (resident)

Probably extant (resident) | |

The species is a specialised diurnal hunter of ungulates, which it captures by using its stamina and cooperative hunting to exhaust them. Its natural competitors are lions and spotted hyenas: the former will kill the dogs where possible, whilst the latter are frequent kleptoparasites.[4]

Like other canids, the African wild dog regurgitates food for its young, but also extends this action to adults, as a central part of the pack's social unit.[5][4][6] The young have the privilege to feed first on carcasses.

The African wild dog has been respected in several hunter-gatherer societies, particularly those of the San people and Prehistoric Egypt.

Etymology and naming

The English language has several names for the African wild dog, including African hunting dog, Cape hunting dog,[7] painted hunting dog,[8] painted dog,[9] painted wolf,[10] and painted lycaon.[11] Though the name "African wild dog" is widely used,[12] "wild dog" is thought by conservation groups to have negative connotations that could be detrimental to its image; one organisation promotes the name "painted wolf",[13][14][15] while the name "painted dog" has been found to be the most likely to counteract negative perceptions.[16]

Taxonomic and evolutionary history

Taxonomy

| Phylogenetic tree of the wolf-like canids with timing in millions of years[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The earliest written reference for the species appears to be from Oppian, who wrote of the thoa, a hybrid between the wolf and leopard, which resembles the former in shape and the latter in colour. Solinus's Collea rerum memorabilium from the third century AD describes a multicoloured wolf-like animal with a mane native to Ethiopia.[11]

The African wild dog was scientifically described in 1820 by Coenraad Jacob Temminck, after examining a specimen from the coast of Mozambique. He named the animal Hyaena picta, erroneously classifying it as a species of hyena. It was later recognised as a canid by Joshua Brookes in 1827, and renamed Lycaon tricolor. The root word of Lycaon is the Greek λυκαίος (lykaios), meaning "wolf-like". The specific epithet pictus (Latin for "painted"), which derived from the original picta, was later returned to it, in conformity with the International Rules on Taxonomic Nomenclature.[17]

Paleontologist George G. Simpson placed the African wild dog, the dhole, and the bush dog together in the subfamily Simocyoninae on the basis of all three species having similarly trenchant carnassials. This grouping was disputed by Juliet Clutton-Brock, who argued that, other than dentition, too many differences exist between the three species to warrant classifying them in a single subfamily.[18]

Evolution

_fig._4_Xenocyon_lycaonoides.png.webp)

The African wild dog possesses the most specialized adaptations among the canids for coat colour, diet, and for pursuing its prey through its cursorial (running) ability. It has a graceful skeleton, and the loss of the first digit on its forefeet increases its stride and speed. This adaptation allows it to pursue prey across open plains for long distances. The teeth are generally carnassial-shaped, and its premolars are the largest relative to body size of any living carnivoran with the exception of the spotted hyena. On the lower carnassials (first lower molars), the talonid has evolved to become a cutting blade for flesh-slicing, with a reduction or loss of the post-carnassial molars. This adaptation also occurs in two other hypercarnivores – the dhole and the bush dog. The African wild dog exhibits one of the most varied coat colours among the mammals. Individuals differ in patterns and colours, indicating a diversity of the underlying genes. The purpose of these coat patterns may be an adaptation for communication, concealment, or temperature regulation. In 2019, a study indicated that the lycaon lineage diverged from Cuon and Canis 1.7 million years ago through this suite of adaptations, and these occurred at the same time as large ungulates (its prey) diversified.[19]

The oldest African wild dog fossil dates back to 200,000 years ago and was found in HaYonim Cave, Israel.[20][1] The evolution of the African wild dog is poorly understood due to the scarcity of fossil finds. Some authors consider the extinct Canis subgenus Xenocyon as ancestral to both the genus Lycaon and the genus Cuon,[21][22][23][24]: p149 which lived throughout Eurasia and Africa from the Early Pleistocene to the early Middle Pleistocene. Others propose that Xenocyon should be reclassified as Lycaon.[1] The species Canis (Xenocyon) falconeri shared the African wild dog's absent first metacarpal (dewclaw), though its dentition was still relatively unspecialised.[1] This connection was rejected by one author because C. (X.) falconeri lacks metacarpal, which is a poor indication of phylogenetic closeness to the African wild dog, and the dentition was too different to imply ancestry.[25]

Another ancestral candidate is the Plio-Pleistocene L. sekowei of South Africa on the basis of distinct accessory cusps on its premolars and anterior accessory cuspids on its lower premolars. These adaptions are found only in Lycaon among living canids, which shows the same adaptations to a hypercarnivorous diet. L. sekowei had not yet lost the first metacarpal absent in L. pictus and was more robust than the modern species, having 10% larger teeth.[25]

The African wild dog genetically diverged from other canid lineages between 1.74 to 1.7 million years ago and is thought to be isolated from gene transfer with other canid species.[26]

Admixture with the dhole

The African wild dog has 78 chromosomes, the same number that species of the genus Canis have.[27] In 2018, whole genome sequencing was used to compare the dhole (Cuon alpinus) with the African wild dog. There was strong evidence of ancient genetic admixture between the two species. Today, their ranges are remote from each other; however, during the Pleistocene era the dhole could be found as far west as Europe. The study proposes that the dhole's distribution may have once included the Middle East, from where it may have admixed with the African wild dog in North Africa. However, there is no evidence of the dhole having existed in the Middle East or North Africa.[28]

Subspecies

As of 2005, five subspecies are recognised by MSW3:[29]

| Subspecies | Description | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|

| Cape wild dog L. p. pictus Temminck, 1820  |

The nominate subspecies is also the largest, weighing 20–25 kg (44–55 lb).[30] It is much more colourful than the East African wild dog,[30] although even within this single subspecies there are geographic variations in coat colour: specimens inhabiting the Cape are characterised by the large amount of orange-yellow fur overlapping the black, the partially yellow backs of the ears, the mostly yellow underparts and a number of whitish hairs on the throat mane. Those in Mozambique are distinguished by the almost equal development of yellow and black on both the upper and underparts of the body, as well as having less white fur than the Cape form.[31] | cacondae (Matschie, 1915), fuchsi (Matschie, 1915), gobabis (Matschie, 1915), krebsi (Matschie, 1915), lalandei (Matschie, 1915), tricolor (Brookes, 1827), typicus (A. Smith, 1833), venatica (Burchell, 1822), windhorni (Matschie, 1915), zuluensis (Thomas, 1904) |

| East African wild dog L. p. lupinus Thomas, 1902 _cropped.jpg.webp) |

This subspecies is distinguished by its very dark coat with very little yellow.[31] | dieseneri (Matschie, 1915), gansseri (Matschie, 1915), hennigi (Matschie, 1915), huebneri (Matschie, 1915), kondoae (Matschie, 1915), lademanni (Matschie, 1915), langheldi (Matschie, 1915), prageri (Matschie, 1912), richteri (Matschie, 1915), ruwanae (Matschie, 1915), ssongaeae (Matschie, 1915), stierlingi (Matschie, 1915), styxi (Matschie, 1915), wintgensi (Matschie, 1915) |

| Somali wild dog L. p. somalicus Thomas, 1904  |

This subspecies is smaller than the East African wild dog, has shorter and coarser fur and has a weaker dentition. Its colour closely approaches that of the Cape wild dog, with the yellow parts being buff.[31] | luchsingeri (Matschie, 1915), matschie (Matschie, 1915), rüppelli (Matschie, 1915), takanus (Matschie, 1915), zedlitzi (Matschie, 1915) |

| Chadian wild dog L. p. sharicus Thomas and Wroughton, 1907 |

Brightly coloured with very short 15 mm (0.6 in) hair. Brain case is fuller than L. p. pictus.[32] | ebermaieri (Matschie, 1915) |

| West African wild dog L. p. manguensis Matschie, 1915  |

The West African wild dog used to be widespread from western to central Africa, from Senegal to Nigeria. Now only two subpopulations survive: one in the Niokolo-Koba National Park of Senegal and the other in the W National Park of Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger.[2][33] It is estimated that 70 adult individuals are left in the wild.[34] | mischlichi (Matschie, 1915) |

Although the species is genetically diverse, these subspecific designations are not universally accepted. East African and Southern African wild dog populations were once thought to be genetically distinct, based on a small number of samples. More recent studies with a larger number of samples showed that extensive intermixing has occurred between East African and Southern African populations in the past. Some unique nuclear and mitochondrial alleles are found in Southern African and northeastern African populations, with a transition zone encompassing Botswana, Zimbabwe and southeastern Tanzania between the two. The West African wild dog population may possess a unique haplotype, thus possibly constituting a truly distinct subspecies.[35] The original Serengeti and Maasai Mara population of painted dogs is known to have possessed a unique genotype, but these genotypes may be extinct.[36]

Description

_(16394165128).jpg.webp)

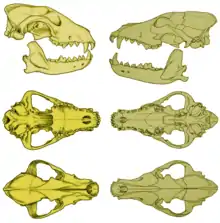

The African wild dog is the bulkiest and most solidly built of African canids.[37] The species stands 60 to 75 cm (24 to 30 in) at the shoulders, measures 71 to 112 cm (28 to 44 in) in head-and-body length and has a tail length of 29 to 41 cm (11 to 16 in). Adults have a weight range of 18 to 36 kg (40 to 79 lb). On average, dogs from East Africa weigh around 20–25 kg (44–55 lb) while in southern Africa, males reportedly weighed a mean of 32.7 kg (72 lb) and females a mean of 24.5 kg (54 lb). By body mass, they are only outsized amongst other extant canids by the gray wolf species complex.[30][38][39] Females are usually 3–7% smaller than males. Compared to members of the genus Canis, the African wild dog is comparatively lean and tall, with outsized ears and lacking dewclaws. The middle two toepads are usually fused. Its dentition differs from that of Canis by the degeneration of the last lower molar, the narrowness of the canines and proportionately large premolars, which are the largest relative to body size of any carnivore other than hyenas.[40] The heel of the lower carnassial M1 is crested with a single, blade-like cusp, which enhances the shearing capacity of the teeth, thus the speed at which prey can be consumed. This feature, termed "trenchant heel", is shared with two other canids: the Asian dhole and the South American bush dog.[7] The skull is relatively shorter and broader than those of other canids.[37]

The fur of the African wild dog differs significantly from that of other canids, consisting entirely of stiff bristle-hairs with no underfur.[37] Adults gradually lose their fur as it ages, with older individuals being almost naked.[41] Colour variation is extreme, and may serve in visual identification, as African wild dogs can recognise each other at distances of 50–100 m (160–330 ft).[40] Some geographic variation is seen in coat colour, with northeastern African specimens tending to be predominantly black with small white and yellow patches, while southern African ones are more brightly coloured, sporting a mix of brown, black and white coats.[7] Much of the species' coat patterning occurs on the trunk and legs. Little variation in facial markings occurs, with the muzzle being black, gradually shading into brown on the cheeks and forehead. A black line extends up the forehead, turning blackish-brown on the back of the ears. A few specimens sport a brown teardrop-shaped mark below the eyes. The back of the head and neck are either brown or yellow. A white patch occasionally occurs behind the fore legs, with some specimens having completely white fore legs, chests and throats. The tail is usually white at the tip, black in the middle and brown at the base. Some specimens lack the white tip entirely, or may have black fur below the white tip. These coat patterns can be asymmetrical, with the left side of the body often having different markings from that of the right.[40]

Distribution and habitat

African wild dogs once ranged across much of sub-Saharan Africa, being absent only in the driest deserts and lowland forests. The species has been largely exterminated in North and West Africa, and its population has greatly reduced in Central Africa and northeast Africa. The majority of the species' population now occurs in Southern Africa and southern East Africa; more specifically in countries such as Botswana, Namibia, and Zimbabwe. However, it is hard to track where they are and how many there are because of the loss of habitat.[2] A stable population comprising more than 370 individuals is present in South Africa, particularly the Kruger National Park.[42]

The African wild dog inhabits mostly savannas and arid zones, generally avoiding forested areas.[30] This preference is likely linked to the animal's hunting habits, which require open areas that does not obstruct vision or impede pursuit.[37] Nevertheless, it will travel through scrub, woodland and montane areas in pursuit of prey. Forest-dwelling populations have been identified, including one in the Harenna Forest, a wet montane forest up to 2,400 m (7,900 ft) in altitude in the Bale Mountains of Ethiopia.[43] At least one record exists of a pack being sighted on the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro.[30] In Zimbabwe, the species has been recorded at altitudes of 1,800 m (5,900 ft).[12] In Ethiopia, they have been found at high altitudes; several live wild dog packs have been sighted at altitudes of 1,900 to 2,800 m (6,200 to 9,200 ft), and a dead individual was found in June 1995 at 4,050 m (13,290 ft) on the Sanetti Plateau.[44]

The species is very rare in North Africa, and the remaining populations may be of high conservation value, as they are likely to be genetically distinct from other African wild dog populations. The African wild dog is mostly absent in West Africa, with the only potentially viable population occurring in Senegal's Niokolo-Koba National Park. African wild dogs are occasionally sighted in other parts of Senegal, Guinea and Mali. In Central Africa, the species is extinct in Gabon, the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of Congo. The only viable populations occur in the Central African Republic, Chad and especially Cameroon. The African wild dog is distributed throughout patches in East Africa, having been eradicated in Uganda and much of Kenya.[45]

Behaviour and ecology

Social and reproductive behaviour

_with_springbok.jpg.webp)

_play_fighting.jpg.webp)

The African wild dog have strong social bonds, stronger than those of sympatric lions and spotted hyenas; thus, solitary living and hunting are extremely rare in the species.[46] It lives in permanent packs consisting of two to 27 adults and yearling pups. The typical pack size in the Kruger National Park and the Maasai Mara is four or five adults, while packs in Moremi and Selous contain eight or nine. However, larger packs have been observed and temporary aggregations of hundreds of individuals may have gathered in response to the seasonal migration of vast springbok herds in Southern Africa.[47] Males and females have separate dominance hierarchies, with the latter usually being led by the oldest female. Males may be led by the oldest male, but these can be supplanted by younger specimens; thus, some packs may contain elderly male former pack leaders. The dominant pair typically monopolises breeding.[40] The species differs from most other social carnivorans in that males remain in the natal pack, while females disperse (a pattern also found in primates such as gorillas, chimpanzees, and red colobuses). Furthermore, males in any given pack tend to outnumber females 3:1.[30] Dispersing females join other packs and evict some of the resident females related to the other pack members, thus preventing inbreeding and allowing the evicted individuals to find new packs of their own and breed.[40] Males rarely disperse, and when they do, they are invariably rejected by other packs already containing males.[30] Although arguably the most social canid, the species lacks the elaborate facial expressions and body language found in the gray wolf, likely because of the African wild dog's less hierarchical social structure. Furthermore, while elaborate facial expressions are important for wolves in re-establishing bonds after long periods of separation from their family groups, they are not as necessary to African wild dogs, which remain together for much longer periods.[18] The species does have an extensive vocal repertoire consisting of twittering, whining, yelping, squealing, whispering, barking, growling, gurling, rumbling, moaning and hooing.[48]

African wild dog populations in East Africa appear to have no fixed breeding season, whereas those in Southern Africa usually breed during the April–July period.[46] During estrus, the female is closely accompanied by a single male, which keeps other members of the same sex at bay.[30] The copulatory tie characteristic of mating in most canids has been reported to be absent[49] or very brief (less than one minute)[50] in African wild dog, possibly an adaptation to the prevalence of larger predators in its environment.[51] The gestation period lasts 69–73 days, with the interval between each pregnancy being 12–14 months typically. The African wild dog produces more pups than any other canid, with litters containing around six to 16 pups, with an average of 10, thus indicating that a single female can produce enough young to form a new pack every year. Because the amount of food necessary to feed more than two litters would be impossible to acquire by the average pack, breeding is strictly limited to the dominant female, which may kill the pups of subordinates. After giving birth, the mother stays close to the pups in the den, while the rest of the pack hunts. She typically drives away pack members approaching the pups until the latter are old enough to eat solid food at three to four weeks of age. The pups leave the den around the age of three weeks and are suckled outside. The pups are weaned at the age of five weeks, when they are fed regurgitated meat by the other pack members. By seven weeks, the pups begin to take on an adult appearance, with noticeable lengthening in the legs, muzzle, and ears. Once the pups reach the age of eight to 10 weeks, the pack abandons the den and the young follow the adults during hunts. The youngest pack members are permitted to eat first on kills, a privilege which ends once they become yearlings.[30] African wild dogs have an average lifespan of about 10 to 11 years in the wild.[52]

When separated from the pack, an African wild dog becomes depressed and can die as a result of broken heart syndrome.[53][54]

Male/female ratio

Packs of African wild dogs have a high ratio of males to females. This is a consequence of the males mostly staying with the pack whilst female offspring disperse and is supported by a changing sex-ratio in consecutive litters. Those born to maiden females contain a higher proportion of males, second litters are half and half and subsequent litters biased towards females with this trend increasing as females get older. As a result, the earlier litters provide stable hunters whilst the higher ratio of dispersals amongst the females stops a pack from getting too big.[55][5]

Sneeze communication and "voting"

Populations in the Okavango Delta have been observed "rallying" before setting out to hunt. Not every rally results in a departure, but departure becomes more likely when more individual dogs "sneeze". These sneezes are characterized by a short, sharp exhale through the nostrils.[56] When members of dominant mating pairs sneeze first, the group is much more likely to depart. If a dominant dog initiates, around three sneezes guarantee departure. When less dominant dogs sneeze first, if enough others also sneeze (about 10), then the group will go hunting. Researchers assert that wild dogs in Botswana, "use a specific vocalization (the sneeze) along with a variable quorum response mechanism in the decision-making process [to go hunting at a particular moment]".[57]

Inbreeding avoidance

Because the African wild dog largely exists in fragmented, small populations, its existence is endangered. Inbreeding avoidance by mate selection is a characteristic of the species and has important potential consequences for population persistence.[58] Inbreeding is rare within natal packs. Inbreeding may have been selected against evolutionarily because it leads to the expression of recessive deleterious alleles.[59] Computer simulations indicate that all populations continuing to avoid incestuous mating will become extinct within 100 years due to the unavailability of unrelated mates.[58] Thus, the impact of reduced numbers of suitable unrelated mates will likely have a severe demographic impact on the future viability of small wild dog populations.[58]

Hunting and diet

The African wild dog is a specialised pack hunter of common medium-sized antelopes.[60] It and the cheetah are the only primarily diurnal African large predators.[30] The African wild dog hunts by approaching prey silently, then chasing it in a pursuit clocking at up to 66 km/h (41 mph) for 10–60 minutes.[47] The average chase covers some 2 km (1.2 mi), during which the prey animal, if large, is repeatedly bitten on the legs, belly, and rump until it stops running, while smaller prey is simply pulled down and torn apart.[5]

African wild dogs adjust their hunting strategy to the particular prey species. They will rush at wildebeest to panic the herd and isolate a vulnerable individual, but pursue territorial antelope species (which defend themselves by running in wide circles) by cutting across the arc to foil their escape. Medium-sized prey is often killed in 2–5 minutes, whereas larger prey such as wildebeest may take half an hour to pull down. Male wild dogs usually perform the task of grabbing dangerous prey, such as warthogs, by the nose.[61] A species-wide study showed that by preference, where available, five prey species were the most regularly selected, namely the greater kudu, Thomson's gazelle, impala, Cape bushbuck and blue wildebeest.[60][62] More specifically, in East Africa, its most common prey is the Thomson's gazelle, while in Central and Southern Africa, it targets impala, reedbuck, kob, lechwe and springbok,[30] and smaller prey such as common duiker, dik-dik, hares, spring hares, insects and cane rats.[46][63] Staple prey sizes are usually between 15 and 200 kg (33 and 441 lb), though some local studies put upper prey sizes as variously 90 to 135 kg (198 to 298 lb). In the case of larger species such as kudu and wildebeest, calves are largely but not exclusively targeted.[60][64][65] However, certain packs in the Serengeti specialized in hunting adult plains zebras weighing up to 240 kg (530 lb) quite frequently.[66] Another study claimed that some prey taken by wild dogs could weigh up to 289 kg (637 lb).[67] This includes African buffalo juveniles during the dry season when herds are small and calves less protected.[68] Footage from Lower Zambezi National Park taken in 2021 showed a large pack of wild dogs hunting an adult, healthy buffalo, though this is apparently extremely rare.[69] One pack was recorded to occasionally prey on bat-eared foxes, rolling on the carcasses before eating them. African wild dogs rarely scavenge, but have on occasion been observed to appropriate carcasses from spotted hyenas, leopards, cheetahs, lions, and animals caught in snares.[12]

Hunting success varies with prey type, vegetation cover and pack size, but African wild dogs tend to be very successful: often more than 60% of their chases end in a kill, sometimes up to 90%.[70] An analysis of 1,119 chases by a pack of six Okavango wild dogs showed that most were short distance uncoordinated chases, and the individual kill rate was only 15.5 percent. Because kills are shared, each dog enjoyed an efficient benefit–cost ratio.[71][72]

Small prey such as rodents, hares and birds are hunted singly, with dangerous prey such as cane rats and Old World porcupines being killed with a quick and well-placed bite to avoid injury. Small prey is eaten entirely, while large animals are stripped of their meat and organs, leaving the skin, head, and skeleton intact.[46][73] The African wild dog is a fast eater, with a pack being able to consume a Thomson's gazelle in 15 minutes. In the wild, the species' consumption is 1.2–5.9 kg (2.6–13.0 lb) per African wild dog a day, with one pack of 17–43 individuals in East Africa having been recorded to kill three animals per day on average.[12]

Unlike most social predators, African wild dogs will regurgitate food for other adults as well as young family members.[46] Pups old enough to eat solid food are given first priority at kills, eating even before the dominant pair; subordinate adult dogs help feed and protect the pups.[74]

Enemies and competitors

Lions dominate African wild dogs and are a major source of mortality for both adults and pups.[75] Population densities are usually low in areas where lions are more abundant.[76] One pack reintroduced into Etosha National Park was wiped out by lions. A population crash in lions in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area during the 1960s resulted in an increase in African wild dog sightings, only for their numbers to decline once the lions recovered.[75] As with other large predators killed by lion prides, the dogs are usually killed and left uneaten by the lions, indicating the competitive rather than predatory nature of the lions' dominance.[77][78] However, a few cases have been reported of old and wounded lions falling prey to African wild dogs.[79][80] On occasion, packs of wild dogs have been observed defending pack members attacked by single lions, sometimes successfully. One pack in the Okavango in March 2016 was photographed by safari guides waging "an incredible fight" against a lioness that attacked a subadult dog at an impala kill, which forced the lioness to retreat, although the subadult dog died. A pack of four wild dogs was observed furiously defending an old adult male dog from a male lion that attacked it at a kill; the dog survived and rejoined the pack.[81]

African wild dogs commonly lose their kills to larger predators.[82] Spotted hyenas are important kleptoparasites[75] and follow packs of African wild dogs to appropriate their kills. They typically inspect areas where wild dogs have rested and eat any food remains they find. When approaching wild dogs at a kill, solitary hyenas approach cautiously and attempt to take off with a piece of meat unnoticed, though they may be mobbed in the attempt. When operating in groups, spotted hyenas are more successful in pirating African wild dog kills, though the latter's greater tendency to assist each other puts them at an advantage against spotted hyenas, which rarely work cooperatively. Cases of African wild dogs scavenging from spotted hyenas are rare. Although African wild dog packs can easily repel solitary hyenas, on the whole, the relationship between the two species is a one-sided benefit for the hyenas,[83] with African wild dog densities being negatively correlated with high hyena populations.[84] Beyond piracy, cases of interspecific killing of African wild dogs by spotted hyenas are documented.[85] African wild dogs are apex predators, only fatally losing contests to larger social carnivores.[86] When briefly unprotected, wild dog pups may occasionally be vulnerable to large eagles, such as the martial eagle, when they venture out of their dens.[87]

Threats and conservation

The African wild dog is primarily threatened by habitat fragmentation, which results to human–wildlife conflict, transmission of infectious diseases and high mortality rates.[2] Surveys in the Central African Republic's Chinko area revealed that the African wild dog population decreased from 160 individuals in 2012 to 26 individuals in 2017. At the same time, transhumant pastoralists from the border area with Sudan moved in the area with their livestock.[86]

The African Wild Dog Conservancy, a non-profit, 501(c)(3), non-governmental organization, began working in 2003 to conserve the African wild dog in northeastern and coastal Kenya, a convergence zone of two biodiversity hotspots. This area largely consists of community lands inhabited by pastoralists. With the help of local people, a pilot study was launched confirming the presence of a population of wild dogs largely unknown to conservationists.[88] Over the next 16 years, local ecological knowledge revealed this area to be a significant refuge for wild dogs and an important wildlife corridor connecting Kenya’s Tsavo National Parks with the Horn of Africa in an increasingly human-dominated landscape. This project has been identified as a wild dog conservation priority by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group.[89][90]

In culture

Ancient Egypt

Depictions of African wild dogs are prominent on cosmetic palettes and other objects from Egypt's predynastic period, likely symbolising order over chaos and the transition between the wild and the domestic dog. Predynastic hunters may have identified with the African wild dog, as the Hunters Palette shows them wearing the animals' tails on their belts. By the dynastic period, African wild dog illustrations became much less represented, and the animal's symbolic role was largely taken over by the wolf.[91][92]

Ethiopia

According to Enno Littmann, the people of Ethiopia's Tigray Region believed that injuring a wild dog with a spear would result in the animal dipping its tail in its wounds and flicking the blood at its assailant, causing instant death. For this reason, Tigrean shepherds used to repel wild dog attacks with pebbles rather than with edged weapons.[93]

San people

The African wild dog also plays a prominent role in the mythology of Southern Africa's San people. In one story, the wild dog is indirectly linked to the origin of death, as the hare is cursed by the moon to be forever hunted by African wild dogs after the hare rebuffs the moon's promise to allow all living things to be reborn after death.[94] Another story has the god Cagn taking revenge on the other gods by sending a group of men transformed into African wild dogs to attack them, though who won the battle is never revealed.[95] The San of Botswana see the African wild dog as the ultimate hunter and traditionally believe that shamans and medicine men can transform themselves into wild dogs. Some San hunters will smear African wild dog bodily fluids on their feet before a hunt, believing that doing so will give them the animal's boldness and agility. Nevertheless, the species does not figure prominently in San rock art, with the only notable example being a frieze in Mount Erongo showing a pack hunting two antelopes.[95]

Ndebele

The Ndebele have a story explaining why the African wild dog hunts in packs: in the beginning, when the first wild dog's wife was sick, the other animals were concerned. An impala went to hare, who was a medicine man. Hare gave Impala a calabash of medicine, warning him not to turn back on the way to Wild Dog's den. Impala was startled by the scent of a leopard and turned back, spilling the medicine. A zebra then went to Hare, who gave him the same medicine along with the same advice. On the way, Zebra turned back when he saw a black mamba, thus breaking the gourd. A moment later, a terrible howling is heard: Wild Dog's wife had died. Wild Dog went outside and saw Zebra standing over the broken gourd of medicine, so Wild Dog and his family chased Zebra and tore him to shreds. To this day, African wild dogs hunt zebras and impalas as revenge for their failure to deliver the medicine which could have saved Wild Dog's wife.[96]

In media

Documentary

- A Wild Dog's Tale (2013), a single painted dog (named Solo by researchers) befriends hyenas and jackals in Okavango, hunting together. Solo feeds and cares for jackal pups.[97][98]

- The Pale Pack, Savage Kingdom, Season 1 (2016), was the story of Botswana African wild dog pack leaders Teemana and Molao written and directed by Brad Bestelink, and narrated by Charles Dance premiered on National Geographic.[99][100]

- Dynasties (2018 TV series), episode 4, Produced by Nick Lyon: Tait is the elderly matriarch of a pack of painted wolves in Zimbabwe's Mana Pools National Park. Her pack is driven out of their territory by Tait's daughter, Blacktip, the matriarch of a rival pack in need of more space for their large family of 32. Their combined territory also shrunk over Tait's lifetime due to the expansion of human, hyena and lion territories. Tait leads her family into the territory of a lion pride in the midst of a drought, with Blacktip's pack in an eight month long pursuit. When Tait died, the pack was observed performing a rare "singing", the purpose of which is unclear.[101]

See also

Explanatory notes

- For a full set of supporting references refer to the note (a) in the phylotree at Evolution of the wolf#Wolf-like canids

References

- Martínez-Navarro, B. & Rook, L. (2003). "Gradual evolution in the African hunting dog lineage: systematic implications". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2 (8): 695–702. Bibcode:2003CRPal...2..695M. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2003.06.002.

- Woodroffe, R. & Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2020) [amended version of 2012 assessment]. "Lycaon pictus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T12436A166502262. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T12436A166502262.en. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- Temminck (1820), Ann. Gen. Sci. Phys., 3:54, pl.35

- "African Wild Dog (Lycaon pictus Temminck, 1820) - WildAfrica.cz - Animal Encyclopedia". Wildafrica.cz. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Creel, Scott; Creel, Nancy Marusha (31 December 2019). The African Wild Dog: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. Princeton University Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-691-20700-1.

- Whittington-Jones, Brendan (2015). African Wild Dogs: On the Front Line. Jacana. ISBN 978-1-4314-2129-9.

- Woodroffe, R.; McNutt, J.W. & Mills, M.G.L. (2004). "African Wild Dog Lycaon pictus". In Sillero-Zubiri, C.; Hoffman, M. & MacDonald, D. W. (eds.). Foxes, Jackals and Dogs: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. pp. 174–183. ISBN 978-2-8317-0786-0.

- Roskov Y.; Abucay L.; Orrell T.; Nicolson D.; Bailly N.; Kirk P.M.; Bourgoin T.; DeWalt R.E.; Decock W.; De Wever A.; Nieukerken E. van; Zarucchi J.; Penev, L., eds. (2018). "Canis lycaon Temminck 1820". Catalogue of Life 2018 Checklist. Catalogue of Life. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- "Painted Dog Conservation - Main page". Painted Dog Conservation.

- "African wild dog, facts and photos". National Geographic. 10 June 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- Smith, C. H. (1839). Dogs, W.H. Lizars, Edinburgh, p. 261–269

- Skinner, J. D. & Chimimba, C. T. (2005). "The African wild dog". The Mammals of the Southern African Sub-region. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 474–480. ISBN 978-0-521-84418-5.

- Scott, Jonathan (1991). Painted Wolves: Wild Dogs of the Serengeti-Mara. Viking Press. p. 8. ISBN 0241124859.

- Kristof, N. D. (2010). "Every (wild) dog has its day". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- "The Painted Wolf Foundation - A Wild Dog's Life". The Painted Wolf Foundation. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- Blades, B. (2020). "What's in a name? An evidence-based approach to understanding the implications of vernacular name on conservation of the painted dog (Lycaon pictus)". Language & Ecology. 2019–2020: 1–27.

- Bothma, J. du P. & Walker, C. (1999). Larger Carnivores of the African Savannas, Springer, pp. 130–157, ISBN 978-3-540-65660-9

- Clutton-Brock, J.; Corbet, G. G.; Hills, M. (1976). "A review of the family Canidae, with a classification by numerical methods". Bull. Br. Mus. (Nat. Hist.). 29: 119–199. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.6922.

- Chavez, Daniel E.; Gronau, Ilan; Hains, Taylor; Kliver, Sergei; Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Wayne, Robert K. (2019). "Comparative genomics provides new insights into the remarkable adaptations of the African wild dog (Lycaon pictus)". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 8329. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.8329C. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44772-5. PMC 6554312. PMID 31171819.

- Stiner, M. C.; Howell, F. C.; Martınez-Navarro, B.; Tchernov, E. & Bar-Yosef, O. (2001). "Outside Africa: Middle Pleistocene Lycaon from Hayonim Cave, Israel". Bollettino della Societa Paleontologica Italiana. 40: 293–302.

- Moulle, P.E.; Echassoux, A.; Lacombat, F. (2006). "Taxonomie du grand canidé de la grotte du Vallonnet (Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, Alpes-Maritimes, France)". L'Anthropologie. 110 (#5): 832–836. doi:10.1016/j.anthro.2006.10.001. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2008. (in French)

- Baryshnikov, Gennady F (2012). "Pleistocene Canidae (Mammalia, Carnivora) from the Paleolithic Kudaro caves in the Caucasus". Russian Journal of Theriology. 11 (#2): 77–120. doi:10.15298/rusjtheriol.11.2.01.

- Cherin, Marco; Bertè, Davide F.; Rook, Lorenzo; Sardella, Raffaele (2013). "Re-Defining Canis etruscus (Canidae, Mammalia): A New Look into the Evolutionary History of Early Pleistocene Dogs Resulting from the Outstanding Fossil Record from Pantalla (Italy)". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 21: 95–110. doi:10.1007/s10914-013-9227-4. S2CID 17083040.

- Wang, Xiaoming; Tedford, Richard H.; Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

- Hartstone-Rose, A.; Werdelin, L.; De Ruiter, D. J.; Berger, L. R. & Churchill, S. E. (2010). "The Plio-pleistocene ancestor of Wild Dogs, Lycaon sekowei n. sp". Journal of Paleontology. 84 (2): 299–308. Bibcode:2010JPal...84..299H. doi:10.1666/09-124.1. S2CID 85585759.

- Chavez, D.E.; Gronau, I.; Hains, T.; Kliver, S.; Koepfli, K.-P. & Wayne, R. K. (2019). "Comparative genomics provides new insights into the remarkable adaptations of the African wild dog (Lycaon pictus)". Scientific Reports. 9 (8329): 8329. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.8329C. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44772-5. PMC 6554312. PMID 31171819.

- Smith, P. J., Enenkel, K. A.E. (2014). Zoology in Early Modern Culture: Intersections of Science, Theology, Philology, and Political and Religious Education: Intersections of Science, Theology, Philology, and Political and Religious Education. Brill. p. 83. ISBN 978-90-04-27917-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Ramos-Madrigal, Jazmín; Niemann, Jonas; Samaniego Castruita, Jose A.; Vieira, Filipe G.; Carøe, Christian; Montero, Marc de Manuel; Kuderna, Lukas; Serres, Aitor; González-Basallote, Víctor Manuel; Liu, Yan-Hu; Wang, Guo-Dong; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Mirarab, Siavash; Fernandes, Carlos; Gaubert, Philippe; Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Budd, Jane; Rueness, Eli Knispel; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Petersen, Bent; Sicheritz-Ponten, Thomas; Bachmann, Lutz; Wiig, Øystein; Hansen, Anders J.; Gilbert, M. Thomas P. (2018). "Interspecific Gene Flow Shaped the Evolution of the Genus Canis". Current Biology. 28 (21): 3441–3449.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.08.041. PMC 6224481. PMID 30344120.

- Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 532–628. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Estes, R. (1992). The behavior guide to African mammals: including hoofed mammals, carnivores, primates. University of California Press. pp. 410–419. ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0.

- Bryden, H. A. (1936), Wild Life in South Africa, George G. Harrap & Company Ltd., pp. 19–20

- Thomas, Oldfield; Wroughton, R.C. (1907). "XLIII.—New mammals from Lake Chad and the Congo, mostly from the collections made during the Alexander-Gosling expedition". Magazine of Natural History. 19: 375.

- Victor Montoro (14 July 2015). "Lions, cheetahs, and wild dogs dwindle in West and Central African protected areas". Mongabay. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- "West African wild dog". Zoological Society of London (ZSL). Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- Edwards, J. (2009). Conservation genetics of African wild dogs Lycaon pictus (Temminck, 1820) in South Africa (Magister Scientiae). Pretoria: University of Pretoria. hdl:2263/29439.

- Woodroffe, Rosie; Ginsberg, Joshua R. (April 1999). "Conserving the African wild dog Lycaon pictus. II. Is there a role for reintroduction?". Oryx. 33 (2): 143–151. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3008.1999.00053.x. S2CID 86776888. See p 147.

- Rosevear, D. R. (1974). The carnivores of West Africa. London : Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). pp. 75–91. ISBN 978-0-565-00723-2.

- McNutt, J. W. (1996). "Adoption in African wild dogs, Lycaon pictus". Journal of Zoology. 240 (1): 163–173. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1996.tb05493.x.

- Castelló, J. R. (2018). Canids of the World: Wolves, Wild Dogs, Foxes, Jackals, Coyotes, and Their Relatives. Princeton University Press. pp.230

- Creel, Scott; Creel, Nancy Marusha (2002). The African Wild Dog: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. Princeton University Press. pp. 1–11. ISBN 978-0-691-01654-2.

- Pole, A.; Gordon, I. J.; Gorman, M. L.; MacAskill, M. (2004). "Prey selection by African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) in southern Zimbabwe". Journal of Zoology. 262 (2): 207–215. doi:10.1017/s0952836903004576.

- Nicholson, Samantha K.; Marneweck, David G.; Lindsey, Peter A.; Marnewick, Kelly; Davies-Mostert, Harriet T. (11 February 2020). "A 20-Year Review of the Status and Distribution of African Wild Dogs (Lycaon pictus) in South Africa". African Journal of Wildlife Research. 50 (1): 8. doi:10.3957/056.050.0008. ISSN 2410-7220. S2CID 213655919.

- Dutson, Guy; Sillero-Zuberi, Claudio (2005). "Forest-dwelling African wild dogs in the Bale Mountains, Ethiopia" (PDF). Canid News. 8 (3): 1–6.

- Malcolm, James R.; Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2001). "Recent records of African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) from Ethiopia". Canid News. 4.

- Fanshawe, J. H.; Ginsberg, J. R.; Sillero-Zubiri, C. & Woodroffe, R. (1997). "The Status and Distribution of Remaining Wild Dog Populations". In Woodroffe, R.; Ginsberg, J. & MacDonald, D. (eds.). Status Survey and Conservation Plan: The African Wild Dog. Gland: IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. pp. 11–56.

- Kingdon, J. (1988). East African mammals: an atlas of evolution in Africa. Vol. Volume 3, Part 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 36–53. ISBN 978-0-226-43721-7.

- Nowak, R. M. (2005). Walker's Carnivores of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-8018-8032-2.

- Robbins, R. L. (October 2000). "Vocal Communication in Free-Ranging African Wild Dogs (Lycaon pictus)". Behaviour. 137 (10): 1271–1298. JSTOR 4535774.

- Kleiman, D. G. (1967). "Some aspects of social behavior in the Canidae". American Zoologist. 7 (2): 365–372. doi:10.1093/icb/7.2.365.

- Creel, S. (1998). "Social organization and effective population size in carnivores". In Caro, T. M. (ed.). Behavioral ecology and conservation biology. Oxford University Press. pp. 246–270. ISBN 978-0-19-510490-5.

- Kleiman, D.G.; Eisenberg, J. F. (1973). "Comparisons of canid and felid social systems from an evolutionary perspective". Animal Behaviour. 21 (4): 637–659. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(73)80088-0. PMID 4798194.

- Allen, Michael Mulheisen; Crystal Allen; Crystal. "Lycaon pictus (African wild dog)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Dogs in the Wild: Defending Wild Dogs ~ How Wild Dogs Recover from 'Broken Hearts'". PBS Nature. 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- "Dogs in the Wild: Defending Wild Dogs". PBS Nature. 31 January 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- "Painted Dogs". Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- Walker, Reena H.; King, Andrew J.; McNutt, J. Weldon; Jordan, Neil R. (13 September 2017). "Sneeze to leave: African wild dogs ( Lycaon pictus ) use variable quorum thresholds facilitated by sneezes in collective decisions". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 284 (1862): 20170347. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.0347. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 5597819. PMID 28878054.

- Walker, R. H.; King, A. J.; McNutt, J. W.; Jordan, N. R. (2017). "Sneeze to leave: African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) use variable quorum thresholds facilitated by sneezes in collective decisions". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 284 (1862): 20170347. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.0347. PMC 5597819. PMID 28878054.

- Becker, P.A.; Miller, P.S.; Gunther, M.S.; Somers, M.J.; Wildt, D.E. & Maldonado, J.E. (2012). "Inbreeding avoidance influences the viability of reintroduced populations of African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus)". PLOS ONE. 7 (5): e37181. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...737181B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037181. PMC 3353914. PMID 22615933.

- Charlesworth, D. & Willis, J. H. (2009). "The genetics of inbreeding depression". Nature Reviews Genetics. 10 (11): 783–96. doi:10.1038/nrg2664. PMID 19834483. S2CID 771357.

- Pole, A.; Gordon, I. J.; Gorman, M. L. & MacAskill, M. (2004). "Prey selection by African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) in southern Zimbabwe". Journal of Zoology. 262 (2): 207–215. doi:10.1017/S0952836903004576.

- Morell, V. (1996). "Hope Rises for Africa's wild dog". International Wildlife. 26 (3): 28–37.

- Hayward, M. W.; O'Brien, J.; Hofmeyr, M. & Kerley, G. I. (2006). "Prey preferences of the African wild dog Lycaon pictus (Canidae: Carnivora): ecological requirements for conservation". Journal of Mammalogy. 87 (6): 1122–1131. doi:10.1644/05-mamm-a-304r2.1.

- "Painted Wolf". Animal Diversity Web.

- Kruger, S. C.; Lawes, M. J. & Maddock, A. H. (1999). "Diet choice and capture success of wild dog (Lycaon pictus) in Hluhluwe-Umfolozi Park, South Africa". Journal of Zoology. 248 (4): 543–551. doi:10.1017/s0952836999008146.

- Ramnanan, R.; Swanepoel, L. H. & Somers, M. J. (2013). "The diet and presence of African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) on private land in the Waterberg region, South Africa". African Journal of Wildlife Research. 43 (1): 68–74. doi:10.3957/056.043.0113. hdl:2263/37231. S2CID 54975768.

- Malcolm, J. R. & Van Lawick, H. (1975). "Notes on wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) hunting zebras". Mammalia. 39 (2): 231–240. doi:10.1515/mamm.1975.39.2.231. S2CID 83740058.

- Clements, H. S.; Tambling, C. J.; Hayward, M. W. & Kerley, G. I. (2014). "An objective approach to determining the weight ranges of prey preferred by and accessible to the five large African carnivores". PLOS ONE. 9 (7): e101054. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j1054C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101054. PMC 4079238. PMID 24988433.

- Krüger, S.; Lawes, M.; Maddock, A. (1999). "Diet choice and capture success of wild dog (Lycaon pictus) in Hluhluwe-Umfolozi Park, South Africa". Journal of Zoology. 248 (4): 543–551. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1999.tb01054.x.

- Nkajeni, U. "WATCH - More than 15 wild dogs take down an adult buffalo". Sunday Times (South Africa). Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- Schaller, G. B. (1973). Golden Shadows, Flying Hooves. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-394-47243-0.

- Hubel, Tatjana Y.; Myatt, Julia P.; Jordan, Neil R.; Dewhirst, Oliver P.; McNutt, J. Weldon; Wilson, Alan M. (April 2016). "Additive opportunistic capture explains group hunting benefits in African wild dogs". Nature Communications. 7 (1): 11033. Bibcode:2016NatCo...711033H. doi:10.1038/ncomms11033. PMC 4820541. PMID 27023355. S2CID 7943459.

- Hubel, T. Y.; Myatt, J. P.; Jordan, N. R.; Dewhirst, O. P.; McNutt, J. W.; Wilson, A. M. (2016). "Energy cost and return for hunting in African wild dogs and cheetahs". Nature Communications. 7 (1): 11034. Bibcode:2016NatCo...711034H. doi:10.1038/ncomms11034. PMC 4820543. PMID 27023457.

- Woodroffe, R.; Lindsey, P. A.; Romañach, S. S. & Ranah, S. M. O. (2007). "African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) can subsist on small prey: implications for conservation". Journal of Mammalogy. 88 (1): 181–193. doi:10.1644/05-mamm-a-405r1.1.

- Nowak, R. M. (2005). Walker's Carnivores of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-8018-8032-2.

- Woodroffe, R. & Ginsberg, J. R. (1997). "Past and Future Causes of Wild Dogs' Population Decline". In Woodroffe, R.; Ginsberg, J. & MacDonald, D. (eds.). Status Survey and Conservation Plan: The African Wild Dog. Gland: IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. pp. 58–73.

- Woodroffe, R.; Ginsberg, J. R. (1999). "Conserving the African wild dog Lycaon pictus. I. Diagnosing and treating causes of decline". Oryx. 33 (2): 132–142. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3008.1999.00052.x.

- Creel, S. & Creel, N. M. (1996). "Limitation of African wild dogs by competition with larger carnivores". Conservation Biology. 10 (2): 526–538. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10020526.x.

- Creel, S. & Creel, N. M. (1998). "Six ecological factors that may limit African wild dogs, Lycaon pictus". Animal Conservation. 1 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.1998.tb00220.x.

- Pienaar, U. de V. (1969). "Predator-prey relationships amongst the larger mammals of the Kruger National Park". Koedoe. 12 (1): 108–176. doi:10.4102/koedoe.v12i1.753.

- Schaller, G. B. (1972). The Serengeti lion: A study of predator-prey relations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-226-73639-6.

- McNutt, J. & Boggs, L. P. (1997). Running Wild: Dispelling the Myths of the African Wild Dog. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books.

- Creel, S. & Creel, M., N. (1998). "Six ecological factors that may limit African wild dogs, Lycaon pictus". Animal Conservation. 1 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.1998.tb00220.x.

- Kruuk, H. (1972). The Spotted Hyena: A Study of Predation and Social Behaviour. University of California Press. pp. 139–141. ISBN 978-0-226-45508-2.

- Creel, S. & Creel, N. M. (2002). The African Wild Dog: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. Princeton University Press. pp. 253–254. ISBN 978-0-691-01654-2.

- Palomares, F. & Caro, T. M. (1999). "Interspecific killing among mammalian carnivores". The American Naturalist. 153 (5): 492–508. doi:10.1086/303189. hdl:10261/51387. PMID 29578790. S2CID 4343007.

- Äbischer, T.; Ibrahim, T.; Hickisch, R.; Furrer, R. D.; Leuenberger, C. & Wegmann, D. (2020). "Apex predators decline after an influx of pastoralists in former Central African Republic hunting zones" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 241: 108326. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108326. S2CID 213766740.

- Jackman, B., & Scott, J. (2012). The marsh lions: the story of an African pride. Bradt Travel Guides.

- McCreery, E.K.; Robbins, R.L. (2004). "Sightings of African wild dogs, Lycaon pictus, in southeastern Kenya" (PDF). Canid News. 7 (4): 1–5.

- Sillero-Zubiri, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Macdonald, D.W. (2004). "Canids: Foxes, Wolves, Jackals and Dogs: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan". Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group, IUCN. pp. 335–336. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- Githiru et al. (2007). African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) from NE Kenya: Recent records and conservation issues. Zoology Department Research Report. National Museum of Kenya.

- Baines, J (1993). "Symbolic roles of canine figures on early monuments". Archéo-Nil: Revue de la société pour l'étude des cultures prépharaoniques de la vallée du Nil. 3: 57–74. doi:10.3406/arnil.1993.1175. S2CID 193657797.

- Hendrickx, S. (2006). The dog, the Lycaon pictus and order over chaos in Predynastic Egypt. [in:] Kroeper, K.; Chłodnicki, M. & Kobusiewicz, M. (eds.), Archaeology of Early Northeastern Africa. Studies in African Archaeology 9. Poznań: Poznań Archaeological Museum: 723–749.

- Littman, Enno (1910). "Publications of the Princeton Expedition to Abyssinia", vol. 2. Leyden : Late E. J. Brill. pp. 79–80

- "Culture Out of Africa". www.dhushara.com. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- De la Harpe R. & De la Harpe, P. (2010). "In search of the African wild dog: the right to survive". Sunbird p. 41. ISBN 978-1-919938-11-0.

- Greaves, Nick (1989). When Hippo was Hairy and other tales from Africa. Bok Books. pp. 35–38. ISBN 978-0-947444-12-9.

- "National Geographic TV Shows, Specials & Documentaries". National Geographic Channel. 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2014.

- "The Amazing Story of Solo, the African Wild Dog Who Lost Her Pack (Video)". The Safarist. 20 December 2014.

- "INTERVIEW: 'Savage Kingdom' returns with wild, wild drama". Hollywood Soapbox. 23 November 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- "The Pale Pack". National Geographic. 17 October 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Shaw, Alfie (2019). "Painted wolf singing ritual filmed for first time". BBC Earth. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020.

Further reading

- Van Lawick, H. & Goodall, J. (1971). Innocent Killers. Houghton Mifflin Company Boston

External links

- painteddog.org, Painted Dog Conservation Website

- painteddog.co.uk/, Painted Dog Conservation United Kingdom Website

- African Wild Dog Conservancy

- African Wild Dog Watch

- Wild Dog conservation in Zimbabwe

- Namibia Nature Foundation Wild Dog Project: Conservation of African wild dogs in Namibia

- at African Wildlife Foundation

- The Zambian Carnivore Programme

- Save the African wild dog

- Wildentrust.org

- Painted Dog Conservation (conservation organization)

- Photos, videos and information from ARKive

- ibream wild dog project