Commodity (Marxism)

In classical political economy and especially Karl Marx's critique of political economy, a commodity is any good or service ("products" or "activities")[1] produced by human labour[2] and offered as a product for general sale on the market.[3] Some other priced goods are also treated as commodities, e.g. human labor-power, works of art and natural resources, even though they may not be produced specifically for the market, or be non-reproducible goods. This problem was extensively debated by Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Karl Rodbertus-Jagetzow, among others. Value and price are not equivalent terms in economics, and theorising the specific relationship of value to market price has been a challenge for both liberal and Marxist economists.

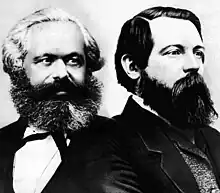

| Part of a series on the |

| Marxian critique of political economy |

|---|

|

Characteristics of commodity

In Marx's theory, a commodity is something that is bought and sold, or exchanged in a relationship of trade.[4]

- It has value, which represents a quantity of human labor.[5] Because it has value, implies that people try to economise its use. A commodity also has a use value[6] and an exchange value.[7]

- It has a use value because, by its intrinsic characteristics, it can satisfy some human need or want, physical or ideal.[8] By nature this is a social use value, i.e. the object is useful not just to the producer but has a use for others generally.[9]

- It has an exchange value, meaning that a commodity can be traded for other commodities, and thus give its owner the benefit of others' labor (the labor done to produce the purchased commodity).[10]

Price is then the monetary expression of exchange-value, but exchange value could also be expressed as a direct trading ratio between two commodities without using money, and goods could be priced using different valuations or criteria.[11]

According to the labor theory of value, product-values in an open market are regulated by the average socially necessary labour time required to produce them, and price relativities of products are ultimately governed by the law of value.[12]

"We are doing everything possible to give work this new status as a social duty and to link it on the one hand with the development of technology, which will create the conditions for greater freedom, and on the other hand with voluntary work based on the Marxist appreciation that one truly reaches a full human condition when no longer compelled to produce by the physical necessity to sell oneself as a commodity."

Historical origins of commodity trade

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

Commodity-trade, Marx argues, historically begins at the boundaries of separate economic communities based otherwise on a non-commercial form of production.[14] Thus, producers trade in those goods of which those producers, have episodic or permanent surpluses to their own requirements, and they aim to obtain different goods with an equal value in return.

Marx refers to this as "simple exchange" which implies what Frederick Engels calls "simple commodity production". At first, goods may not even be intentionally produced for the explicit purpose of exchanging them, but as a regular market for goods develops and a cash economy grows, this becomes more and more the case, and production increasingly becomes integrated in commodity trade. "The product becomes a commodity" and "exchange value of the commodity acquires a separate existence alongside the commodity"[15]

Even so, in simple commodity production, not all inputs and outputs of the production process are necessarily commodities or priced goods, and it is compatible with a variety of different relations of production ranging from self-employment and family labour to serfdom and slavery. Typically, however, it is the producer himself who trades his surpluses.

However, as the division of labour becomes more complex, a class of merchants emerges which specialises in trading commodities, buying here and selling there, without producing products themselves, and parallel to this, property owners emerge who extend credit and charge rents. This process goes together with the increased use of money, and the aim of merchants, bankers and renters becomes to gain income from the trade, by acting as intermediaries between producers and consumers.

The transformation of a labor-product into a commodity (its "marketing") is in reality not a simple process, but has many technical and social preconditions. These often include the following ten (10) main ones:

- The existence of a reliable supply of a product, or at least a surplus or surplus product.

- The existence of a social need for it (a market demand) that must be met through trade, or at any event cannot be met otherwise.

- The legally sanctioned assertion of private ownership rights to the commodity.

- The enforcement of these rights, so that ownership is secure.

- The transferability of these private rights from one owner to another.

- The right to buy and sell the commodity, and/or obtain (privately) and keep income from such trade

- The (physical) transferability of the commodity itself, i.e. the ability to store, package, preserve and transport it from one owner to another.

- The imposition of exclusivity of access to the commodity.

- The possibility of the owner to use or consume the commodity privately.

- Guarantees about the quality and safety of the commodity, and possibly a guarantee of replacement or service, should it fail to function as intended.

Thus, the "commodification" of a good or service often involves a considerable practical accomplishment in trade. It is a process that may be influenced not just by economic or technical factors, but also political and cultural factors, insofar as it involves property rights, claims to access to resources, and guarantees about quality or safety of use.

In absolute terms, exchange values can also be measured as quantities of average labour-hours. Commodities which contain the same amount of socially necessary labor have the same exchange value. By contrast, prices are normally measured in money-units. For practical purposes, prices are, however, usually preferable to labour-hours, as units of account, although in capitalist work processes the two are related to each other (see labor power).

Forms of commodity trade

The seven basic forms of commodity trade can be summarised as follows:

- M-C (an act of purchase: a sum of money purchases a commodity, or "money is changed into a commodity")[16]

- C-M (an act of sale: a commodity is sold for money)[17]

- M-M' (a sum of money is lent out at interest to obtain more money, or, one currency or financial claim is traded for another; "money begets money")[18]

- C-C' (countertrade, in which a commodity trades directly for a different commodity, with money possibly being used as an accounting referent, for example, food for oil, or weapons for diamonds)

- C-M-C' (a commodity is sold for money, which buys another, different commodity with an equal or higher value)

- M-C-M' (money is used to buy a commodity which is resold to obtain a larger sum of money)[19]

- M-C...P...-C'-M' (money buys means of production and labour power used in production to create a new commodity, which is sold for more money than the original outlay; "the circular course of capital")[20]

The hyphens ("-") here refer to a transaction applying to an exchange involving goods or money; the dots in the last-mentioned circuit ("...") indicate that a value-forming process ("P") occurs in between purchase of commodities and the sales of different commodities. Thus, while at first merchants are intermediaries between producers and consumers, later capitalist production becomes an intermediary between buyers and sellers of commodities. In that case, the valuation of labour is determined by the value of its products.

The reifying effects of universalised trade in commodities, involving a process Marx calls "commodity fetishism",[21] mean that social relations become expressed as relations between things;[22] for example, price relations. Markets mediate a complex network of interdependencies and supply chains emerging among people who may not even know who produced the goods they buy, or where they were produced.

Since no one agency can control or regulate the myriad of transactions that occur (apart from blocking some trade here, and permitting it there), the whole of production falls under the sway of the law of value, and economics becomes a science aiming to understand market behaviour, i.e. the aggregate effects of a multitude of people interacting in markets. How quantities of use-values are allocated in a market economy depends mainly on their exchange value, and this allocation is mediated by the "cash nexus".

In Marx's analysis of the capitalist mode of production, commodity sales increase the amount of exchange-value in the possession of the owners of capital, i.e., they yield profit and thus augment their capital (capital accumulation).

Cost structure of commodities

In considering the unit cost of a capitalistically produced commodity (in contrast to simple commodity production), Marx claims that the value of any such commodity is reducible to four components equal to:

- Variable capital used up to produce it.

- Fixed and circulating constant capital used up per unit.

- Incidental expenses which cost labour-time (faux frais of production).

- Surplus value per unit.

These components reflect respectively labour costs, the cost of materials and operating expenses including depreciation, and generic profit.

In capitalism, Marx argues, commodity values are commercially expressed as the prices of production of commodities (cost-price + average profit). Prices of production are established jointly by average input costs and by the ruling profit margins applying to outputs sold. They reflect the fact that production has become totally integrated into the circuits of commodity trade, in which capital accumulation becomes the dominant motive. But what prices of production simultaneously hide is the social nature of the valorisation process, i.e. how an increase in capital-value occurs through production.

Likewise, in considering the gross output of capitalist production in an economy as a whole, Marx divides its value into these four components. He argues that the total new value added in production, which he calls the value product, consists of the equivalent of variable capital, plus surplus value. Thus, the workers produce by their labor both a new value equal to their own wages, plus an additional new value which is claimed by capitalists by virtue of their ownership and supply of productive capital.

By producing new capital in the form of new commodities, Marx argues the working class continuously reproduces the capitalist relations of production; by their work, workers create a new value distributed as both labour-income and property-income. If, as free workers, they choose to stop working, the system begins to break down; hence, capitalist civilisation strongly emphasizes the work ethic, regardless of religious belief. People must work, because work is the source of new value, profits and capital.

Pseudo-commodities

Marx acknowledged explicitly that not all commodities are products of human labour; all kinds of things can be traded "as if" they are commodities, so long as property rights can be attached to them. These are "fictitious commodities" or "pseudo-commodities" or "fiduciary commodities", i.e. their existence as commodities is only nominal or conventional. They may not even be tangible objects, but exist only ideally. A property right or financial claim, for instance, may be traded as a commodity.

See also

Notes

- Karl Marx, "Outlines of the Critique of Political Economy" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 28 (International Publishers: New York, 1986) p. 80.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume I (International Publishers: New York, 1967) p. 38 and also "Capital" as contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 35, p. 48.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume I, p. 36 and also in "Capital" as contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 35, p. 46.

- Karl Marx, "A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 29 (International Publishers: New York, 1987) p. 270.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume I, (International Publishers: New York, 1967) p. 38 and "Capital" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 35 (International Publishers: New York, 1996) p. 48.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume I, p. 35 and "Capital" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 35, p. 45.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume I, p. 36 and "Capital" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 35, p. 46.

- Karl Marx, "A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 29 (International Publishers: New York, 1987) p. 269.

- Karl Marx, "A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 29, p. 270.

- Karl Marx, "Outlines of the Critique of Political Economy" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 28 (International Publishers: New York, 1986) pp. 167-168.

- Karl Marx, "Outlines of the Critique of Political Economy" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 28, p. 148.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume I (International Publishers: New York, 1967) p. 39 and "Capital" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 35 (International Publishers: New York, 1996) p. 49.

- A letter from Che Guevara to Carlos Quijano, published at Marcha as "From Algiers, for Marcha : The Cuban Revolution Today" (12 March 1965) "Socialism and Man in Cuba"

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume I, p. 87 and "Capital" as contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 35, p. 98.

- Karl Marx, "Outlines of the Critique of Political Capital" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 28, p. 102.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume I, p. 147 and "Capital" as contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 35, p. 159.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume I, p. 147 and "Capital" as contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 35. p. 159.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume I, p. 155 and "Capital" as contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 35, p. 166.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume I, p. 150 and "Capital" as contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 35, p. 161.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume II (International Publishers: New York, 1967) p. 56.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume I, pp. 71–83 and "Capital" as contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 35, pp. 81–94.

- Karl Marx, Capital, pp. 71–72 and "Capital" as contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 35, pp. 81–82.

References

The concept of the commodity is explored at length by Marx in the following works:

- Contribution to a Critique of Political Economy

- Das Kapital Volume 1 Part 1 Chapter 1

- Commodities — from the first chapter of Das Capital

A useful commentary on the Marxian concept is provided in: Costas Lapavitsas, "Commodities and Gifts: Why Commodities Represent More than Market Relations". Science & Society, Vol 68, # 1, Spring 2004.

Both commodity and commodification play an important role in the critical approaches to the political economy of communication, e.g.: Prodnik, Jernej (2012). "A Note on the Ongoing Processes of Commodification: From the Audience Commodity to the Social Factory". triple-C: Cognition, Communication, Co-operation (Vol. 10, No. 2) - special issue "Marx is Back" (edited by Christian Fuchs and Vincent Mosco). pp. 274–301. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

Further reading

- Jack P. Manno, Privileged Goods: Commoditization and Its Impact on Environment and Society. CRC Press, 1999.