Monier Monier-Williams

Sir Monier Monier-Williams KCIE (/ˈmɒniər/; né Williams; 12 November 1819 – 11 April 1899) was a British scholar who was the second Boden Professor of Sanskrit at Oxford University, England. He studied, documented and taught Asian languages, especially Sanskrit, Persian and Hindustani.

Monier Monier-Williams | |

|---|---|

Photo of Monier Monier-Williams by Lewis Carroll | |

| Born | Monier Williams 12 November 1819 Bombay, Bombay Presidency, British India |

| Died | 11 April 1899 (aged 79) Cannes, France |

| Education | King's College School, Balliol College, Oxford; East India Company College; University College, Oxford |

| Known for | Boden Professor of Sanskrit; Sanskrit–English dictionary |

| Awards | Knight Bachelor; Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire |

Early life

Monier Williams was born in Bombay, the son of Colonel Monier Williams, surveyor-general in the Bombay presidency. His surname was "Williams" until 1887, when he added his given name to his surname to create the hyphenated "Monier-Williams". In 1822, he was sent to England to be educated at private schools at Hove, Chelsea and Finchley. He was educated at King's College School, Balliol College, Oxford (1838–40), the East India Company College (1840–41) and University College, Oxford (1841–44). He took a fourth-class honours degree in Literae Humaniores in 1844.[1]

He married Julia Grantham in 1848. They had six sons and one daughter. He died, aged 79, in Cannes, France.[2]

In 1874 he bought and lived in Enfield House, Ventnor, on the Isle of Wight where he and his family lived until at least 1881. (The 1881 census records the occupant was 61-year-old Professor Monier Monier-Williams; his wife, Julia; and two children, Montague (20) and Ella (22).)

Career

Monier Williams taught Asian languages at the East India Company College from 1844 until 1858[3][4] when company rule in India ended after the 1857 rebellion. He came to national prominence during the 1860 election campaign for the Boden Chair of Sanskrit at Oxford University, in which he stood against Max Müller.

The vacancy followed the death of Horace Hayman Wilson in 1860. Wilson had started the university's collection of Sanskrit manuscripts upon taking the chair in 1831, and had indicated his preference that Williams should be his successor. The campaign was notoriously acrimonious. Müller was known for his liberal religious views and his philosophical speculations based on his reading of Vedic literature. Monier Williams was seen as a less brilliant scholar, but had a detailed practical knowledge of India itself, and of actual religious practices in modern Hinduism. Müller, in contrast, had never visited India.[5]

Both candidates had to emphasise their support for Christian evangelisation in India, since that was the basis on which the professorship had been funded by its founder. Monier Williams' dedication to Christianisation was not doubted, unlike Müller's.[6] Monier Williams also stated that his aims were practical rather than speculative. "Englishmen are too practical to study a language very philosophically", he wrote.[5]

After his appointment to the professorship Williams declared from the outset that the conversion of India to the Christian religion should be one of the aims of orientalist scholarship.[6] In his book Hinduism, published by SPCK in 1877, he predicted the demise of the Hindu religion and called for Christian evangelism to ward off the spread of Islam.[6] According to Saurabh Dube this work is "widely credited to have introduced the term Hinduism into general English usage"[7] while David N. Lorenzen cites the book along with India, and India Missions: Including Sketches of the Gigantic System of Hinduism, Both in Theory and Practice : Also Notices of Some of the Principal Agencies Employed in Conducting the Process of Indian Evangelization[8][9]

Writings and foundations

When Monier Williams founded the University's Indian Institute in 1883, it provided both an academic focus and also a training ground for the Indian Civil Service.[2] Since the early 1870s Monier Williams planned this institution. His vision was the better acquaintance of England and India. On this account he supported academic research into Indian culture. Monier Williams travelled to India in 1875, 1876 and 1883 to finance his project by fundraising. He gained the support of Indian native princes. In 1883 the Prince of Wales laid the foundation stone; the building was inaugurated in 1896 by Lord George Hamilton. The Institute closed on Indian independence in 1947.

In his writings on Hinduism Monier Williams argued that the Advaita Vedanta system best represented the Vedic ideal and was the "highest way to salvation" in Hinduism. He considered the more popular traditions of karma and bhakti to be of lesser spiritual value. However, he argued that Hinduism is a complex "huge polygon or irregular multilateral figure" that was unified by Sanskrit literature. He stated that "no description of Hinduism can be exhaustive which does not touch on almost every religious and philosophical idea that the world has ever known."[6]

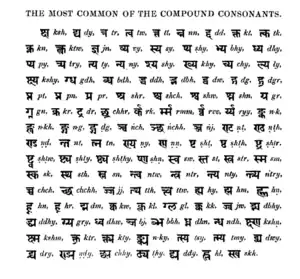

Monier-Williams compiled a Sanskrit–English dictionary, based on the earlier Petersburg Sanskrit Dictionary,[10] which was published in 1872. A later revised edition was published in 1899 with collaboration by Ernst Leumann and Carl Cappeller (sv).[11]

Honours

He was knighted in 1876, and was made KCIE in 1887, when he adopted his given name of Monier as an additional surname. He was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1886.[12]

He also received the following academic honours: Honorary DCL, Oxford, 1875; LLD, Calcutta, 1876; Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford, 1880; Honorary PhD, Göttingen, 1880s; Vice-President, Royal Asiatic Society, 1890; Honorary Fellow of University College, Oxford, 1892.[2]

Published works

Translations

Monier-Williams's translations include that of Kālidāsa's plays Vikramorvasi (1849)[13] and Śākuntala (1853; 2nd ed. 1876).[14]

- Translation of Shakuntala (1853)

- Hindu Literature: comprising the Book of Good Counsels, Nala and Damayanti, the Rámáyana and Śakoontalá

Original works

- An Elementary Grammar of the Sanscrit Language: Partly in the Roman Character, Arranged According to a New Theory, in Reference Especially to the Classical Languages; with Short Extracts in Easy Prose. To which is Added, a Selection from the Institutes of Manu, with Copious References to the Grammar, and an English Translation. W. H. Allen & Company. 1846.

- Original papers illustrating the history of the application of the Roman alphabet to the languages of India: Edited by Monier Williams (1859) Modern Reprint

- Indian Wisdom, Or, Examples of the Religious, Philosophical, and Ethical Doctrines of the Hindūs. London: Oxford. 1875.

- Hinduism. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. 1877.

- Modern India and the Indians: Being a Series of Impressions, Notes, and Essays. Trübner and Company. 1878.

- Translation of Shikshapatri – The manuscript of the principal scripture Sir John Malcolm received from Swaminarayan on 26 February 1830 when he was serving as the Governor of Bombay Presidency, Imperial India. Currently preserved at Bodleian Library.

- Brahmanism and Hinduism (1883)

- Buddhism, in its connexion with Brahmanism and Hinduism, and in its contrast with Christianity (1889)[15]

- Sanskrit-English Dictionary, ISBN 0-19-864308-X.

- A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European languages, Monier Monier-Williams, revised by E. Leumann, C. Cappeller, et al. 1899, Clarendon Press, Oxford

- A Practical Grammar of the Sanskrit Language, Arranged with Reference to the Classical Languages of Europe, for the Use of English Students, Oxford: Clarendon, 1857, enlarged and improved Fourth Edition 1887

Notes

- Oxford University Calendar 1895, Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1895, p.131.

- Macdonell 1901.

- Memorials of old Haileybury College. A. Constable and Company. 1894.

- "Review of Memorials of Old Haileybury College by Sir Monier Monier-Williams and other Contributors". The Quarterly Review. 179: 224–243. July 1894.

- Nirad C. Chaudhuri, Scholar Extraordinary, The Life of Professor the Right Honourable Friedrich Max Muller, P.C., Chatto and Windus, 1974, pp. 221–231.

- Terence Thomas, The British: their religious beliefs and practices, 1800–1986, Routledge, 1988, pp. 85–88.

- Saurabh Dube (1998). Untouchable Pasts: Religion, Identity, and Power among a Central Indian Community, 1780–1950. SUNY Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-7914-3687-5.

- Alexander Duff (1839). India, and India Missions: Including Sketches of the Gigantic System of Hinduism, Both in Theory and Practice : Also Notices of Some of the Principal Agencies Employed in Conducting the Process of Indian Evangelization, &c. &c. J. Johnstone. for popularising of the term.

- David N. Lorenzen (2006). Who Invented Hinduism: Essays on Religion in History. Yoda Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-81-902272-6-1.

- Kamalakaran, Ajay (12 April 2014). "St Petersburg's illustrious Sanskrit connections". www.rbth.com. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- Bloomfield, Maurice (1900). "A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages by Monier Monier-Williams; E. Leumann; C. Cappeller". The American Journal of Philology. 21 (3): 323–327. doi:10.2307/287725. hdl:2027/mdp.39015016641824. JSTOR 287725.

- "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- Schuyler, Jr., Montgomery (1902). "Bibliography of Kālidāsa's Mālavikāgnimitra and Vikramorvaçī". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 23: 93–101. doi:10.2307/592384. JSTOR 592384.

- Schuyler, Jr., Montgomery (1901). "The Editions and Translations of Çakuntalā". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 22: 237–248. doi:10.2307/592432. JSTOR 592432.

- "Buddhism in Its Connexion with Brahmanism and Hinduism and in Its Contrast with Christianity". The Old Testament Student. 8 (10): 389–390. June 1889. doi:10.1086/470215. JSTOR 3156561.

References

- Katz, J. B. (2004). "Williams, Sir Monier Monier-". In Katz, J. B (ed.). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (October 2007 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18955. Retrieved 31 January 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Attribution

- Macdonell, Arthur Anthony (1901). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 186–187.

External links

- SpokenSankrit Online Free Dictionary

- Cologne Digital Sanskrit Dictionaries (Searchable), Monier-Williams' Sanskrit-English Dictionary

- Biography of Sir Monier Monier-Williams, Dr. Gillian Evison, Digital Shikshapatri

- Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Searchable

- Monier-Williams Shikshapatri manuscript, Digital Shikshapatri

- The Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies

- Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary: DICT and HTML versions

- Works by Monier Monier-Williams at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Monier Monier-Williams at Internet Archive