Bernier's teal

Bernier's teal (Anas bernieri), also known as the Madagascar teal, is a species of duck in the genus Anas. It is endemic to Madagascar, where it is found only along the west coast. Part of the "grey teal" complex found throughout Australasia, it is most closely related to the Andaman teal.

| Bernier's teal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Anas |

| Species: | A. bernieri |

| Binomial name | |

| Anas bernieri (Hartlaub, 1860) | |

| |

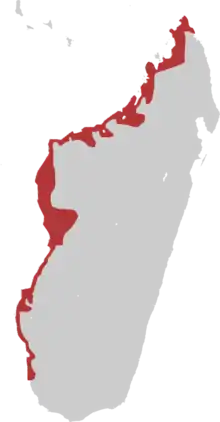

| Distribution of the Bernier's teal | |

Taxonomy

The Bernier's teal was first described by the German ornithologist Gustav Hartlaub in 1860 under the binomial name Querquedula bernieri.[3][4] It is one of many dabbling ducks in the genus Anas.[5] It is one of the "grey teals", a group of related ducks found across Australasia. DNA studies suggest that it may have been a sister species with Sauzier's teal (which was found on the nearby islands of Mauritius and Réunion until it became extinct). Studies further suggest that its closest living relative is the Andaman teal, and confirm that it is related to the gray teal.[6] There are no subspecies.[7]

The duck's common and species names both commemorate Chevalier Bernier, a French naval surgeon and naturalist who collected nearly 200 specimens of various species while stationed in Madagascar.[8] The genus name Anas is a Latin word meaning "duck".[9]

Description

This is a small duck, measuring 40 to 45 cm (16 to 18 in) in length,[10][nb 1] and ranging from 320 to 405 grams (11.3 to 14.3 oz) in mass; males average slightly heavier than females.[12] Adult and immature birds of both sexes look the same, though males are slightly larger than females. The plumage is predominantly warm brown. The bill is reddish, and the legs and feet are a dull reddish-orange.[10]

Range and habitat

Bernier's teal is endemic to the island of Madagascar, where it is found in mangrove forests. It rarely leaves this habitat, where it favors open shallow ponds and lakes, mostly brackish. Its range encompasses the whole of the west coast and the extreme north-east. It is known to breed at a few sites, central and north-west coasts.[1] Subfossil evidence from the Holocene period shows that the teal formerly had a much wider distribution across the island.[13]

Behaviour

Voice

The male Bernier's teal whistles, while the female's call is described as "a croaking quak".[10]

Diet and feeding

Bernier's teal typically spends much of its day actively feeding. It wades at the edge of shallow water, filtering mud and dabbling at the water's surface.[10] It feeds on invertebrates, plant materials, and insects.

Breeding

All known nests of wild Bernier's teal have been found either above or close to water in grey mangrove trees, in holes 1–3 m (3.3–9.8 ft) above the water's surface. In captivity, the species will also use nest boxes. The birds add no materials to the nest. Instead, the female lays her eggs directly on floor of the cavity, covering them initially with wood shavings or rotting bits of wood and later with down feathers from her own breast. In captivity, clutch sizes varied from 3 to 9, with an average of 6.75 eggs per female. The eggs are pale buff in colour, smooth and elliptical in shape, measuring 46.0 mm × 34.6 mm (1.81 in × 1.36 in) on average. This is smaller than the eggs of any of the other "grey teals". Only the female incubates the eggs.[14]

Conservation status

Bernier's teal is on the verge of extinction. There are only about 1500 left in the world. The reason these ducks are on the verge of extinction is because their natural habitat, mangrove forests, are being destroyed for timber and fuel, and to expand cultivation. Hunting for food is also a threat.[15]

The species is now held in wildfowl collections throughout the world, and several captive breeding programs exist. The Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust on Jersey, for example, has reared nearly 100 since starting their breeding program in 1995.[16] In the US, Sylvan Heights Bird Park in North Carolina and the Louisville Zoo in Kentucky have both successfully fledged ducklings.[17][18]

Note

- By convention, length is measured from the tip of the bill to the tip of the tail on a dead bird (or skin) laid on its back.[11]

References

- BirdLife International (2013). "Anas bernieri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- Hartlaub, Gustav (1860). "Systematische Uebersicht der Vögel Madagascars". Journal für Ornithologie (in German and Latin). 8 (45): 161–180 [173–174]. doi:10.1007/bf02015735. S2CID 40507234.

- Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-list of Birds of the World. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 467.

- "ITIS Report: Anas". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- Kear, Janet, ed. (2005). Ducks, Geese and Swans: Species accounts (Cairina to Mergus). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 452. ISBN 978-0-19-861009-0.

- Monroe, Burt L. (1997). A World Checklist of Birds. New Haven, CT, US: Yale University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-300-07083-5.

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2014). The Eponym Dictionary of Birds. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4729-0574-1.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Names. London, UK: Christopher Helm. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Morris, Pete; Hawkins, Frank (1998). Birds of Madagascar: A Photographic Guide. Mountfield, UK: Pica Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-873403-45-7.

- Cramp, Stanley, ed. (1977). Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa: Birds of the Western Palearctic, Volume 1, Ostrich to Ducks. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-857358-6.

- Dunning Jr., John Barnard, ed. (2008). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4200-6444-5.

- Goodman, S.M. (1999). Adams, N.J.; Slotow, R.H. (eds.). "Holocene bird subfossils from the sites of Ampasambazimba, Antsirabe and Ampoza, Madagascar:Changes in the avifauna of south central Madagascar over the past few millennia". Proceedings of the 22nd International Ornithological Congress, Durban. Johannesburg, South Africa: BirdLife South Africa. pp. 3071–3083. Archived from the original on 2014-05-19.

- Young, H. Glyn; Lewis, Richard E.; Razafindrajao, Felix (2001). "A description of the nest and eggs of the Madagascar Teal Anas bernieri". Bull. B.O.C. 121 (1): 64–67.

- Hirschfeld, Erik; Swash, Andy; Still, Robert (2013). The World's Rarest Birds. Princeton, NJ, US: Princeton University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4008-4490-6.

- "Madagascar Teal". Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- "Madagascar Teal Breeding Program". Sylvan Heights Bird Park. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- House, Kelly (19 June 2009). "Zoo's rare duckling not in danger of being found ugly". Courier Journal. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.