Tamil Nadu Legislative Council

Tamil Nadu Legislative Council was the upper house of the former bicameral legislature of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It began its existence as Madras Legislative Council, the first provincial legislature for Madras Presidency. It was initially created as an advisory body in 1861, by the British colonial government. It was established by the Indian Councils Act 1861, enacted in the British parliament in the aftermath of the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Its role and strength were later expanded by the second Council Act of 1892. Limited election was introduced in 1909. The Council became a unicameral legislative body in 1921 and eventually the upper chamber of a bicameral legislature in 1937. After India became independent in 1947, it continued to be the upper chamber of the legislature of Madras State, one of the successor states to the Madras Presidency. It was renamed as the Tamil Nadu Legislative Council when the state was renamed as Tamil Nadu in 1969. The Council was abolished by the M. G. Ramachandran administration on 1 November 1986. In 2010 the DMK regime headed by M. Karunanidhi tried to revive the Council. The former AIADMK regime (2016-2021) expressed its intention not to revive the council and passed a resolution in the Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly in this regard.

Tamil Nadu Legislative Council | |

|---|---|

| Tamil Nadu | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

Term limits | 6 years |

| History | |

| Established | 1861 |

| Disbanded | 1986 |

| Seats | 78 |

| Elections | |

| Proportional representation, First past the post and Nominations | |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Fort St. George 13.081539°N 80.285718°E | |

History and evolution

Origin

The first Indian Councils Act of 1861 set up the Madras Legislative Council as an advisory body through which the colonial administration obtained advice and assistance. The Act empowered the provincial Governor to nominate four non-English Indian members to the council for the first time. Under the Act, the nominated members were allowed to move their own bills and vote on bills introduced in the council. However, they were not allowed to question the executive, move resolutions or examine the budget. Also they could not interfere with the laws passed by the Central Legislature. The Governor was also the president of the Council and he had complete authority over when, where and how long to convene the Council and what to discuss. Two members of his Executive Council and the Advocate-General of Madras were also allowed to participate and vote in the Council. The Indians nominated under this Act were mostly zamindars and ryotwari landowners, who often benefited from their association with the colonial government. Supportive members were often re-nominated for several terms. G. N. Ganapathy Rao was nominated eight times, Humayun Jah Bahadur was a member for 23 years, T. Rama Rao and P. Chentsal Rao were members for six years each. Other prominent members during the period included V. Bhashyam Aiyangar, S. Subramania Iyer and C. Sankaran Nair. The Council met infrequently and in some years (1874 and 1892) was not convened even once. The maximum of number of times it met in a year was eighteen. The Governor preferred to convene the Council at his summer retreat Udagamandalam, much to the displeasure of the Indian members. The few times when the Council met, it was for only a few hours with bills and resolutions being rushed through.[1]

Expansion

| Years | No of Days |

|---|---|

| 1906 | 2 |

| 1897,1901 | 3 |

| 1894,1907 | 4 |

| 1896,1898,1909 | 5 |

| 1899, 1902, 1903, 1904 | 6 |

| 1900 | 7 |

| 1895,1905 | 8 |

| 1893 | 9 |

In 1892, the role of the Council was expanded by the Indian Councils Act of 1892. The Act increased the number of additional members of the Council to a maximum of 20, of whom not more than nine had to be officials. The Act introduced the method of election for the Council, but did not mention word "election" explicitly. The elected members were officially called as "nominated" members and their method of election was described as "recommendation". Such "recommendations" were made by district boards, universities, municipalities and other associations. The term of the members was fixed at two years. The Council could also discuss the annual financial statement and ask questions subject to certain limitations.[2] Thirty eight Indian members were "nominated" in the eight elections during 1893-1909 when this Act was in effect. C. Jambulingam Mudaliar, N. Subba Rao Pantulu, P. Kesava Pillai and C. Vijayaraghavachariar representing southern group of district boards, Kruthiventi Perraju Pantulu of the northern group of municipalities, C. Sankaran Nair and P. Rangaiah Naidu from the Corporation of Madras and P. S. Sivaswami Iyer, V. Krishnaswamy Iyer and M. Krishnan Nair from the University of Madras were some of the active members.[1] However, over a period of time, representation by Indian members dwindled, for example, the position of Bashyam Iyengar and Sankaran Nayar in 1902 was occupied by Acworth and Sir George Moore.[3] The council did not meet more than 9 days in a year during the time the Act was in effect.[1]

Further expansion

| Constituency | No of Members |

|---|---|

| District boards and Municipalities | 10 |

| University of Madras | 1 |

| South India Chamber of Commerce | 1 |

| Madras Traders Association | 1 |

| Zamindars | 2 |

| Large landholders | 3 |

| Muslims | 2 |

| Planters | 1 |

The Indian Councils Act 1909 (popularly called as "Minto-Morley Reforms"), officially introduced the method of electing members to the Council. But it did not provide for direct election of the members. It abolished automatic official (executive) majorities in the Council and gave its members the power to move resolutions upon matters of general public interest and the budget and also to ask supplementary questions.[2] There were a total of 21 elected members and 21 nominated members. The Act allowed up to 16 nominated members to be official and the remaining five were required to be non-officials. The Governor was also authorised to nominate two experts whenever necessary. As before, the Governor, his two executive council members and the Advocate-General were also members of the Council. P. Kesava Pillai, A. S. Krishna Rao, N. Krishnaswami Iyengar, B. N. Sarma, B. V. Narasimha Iyer, K. Perraju Pantulu, T. V. Seshagiri Iyer, P. Siva Rao, V. S. Srinivasa Sastri, P. Theagaraya Chetty and Yakub Hasan Sait were among the active members.

Diarchy (1920-37)

Based on the recommendations of the Montague-Chelmsford report, the Government of India Act of 1919 was enacted. The Act enlarged the provincial legislative councils and increased the strength of elected members to be greater than that of nominated and official members. It introduced a system of dyarchy in the Provinces. Although this Act brought about representative Government in India, the Governor was empowered with overriding powers. It classified the subjects as belonging to either the Centre or the Provinces. The Governor General could override any law passed by the Provincial councils. It brought about the concept of "Partial Responsible Government" in the provinces. Provincial subjects were divided into two categories - reserved and transferred. Education, Sanitation, Local self-government, Agriculture and Industries were listed as the transferred subjects. Law, Finance, Revenue and Home affairs were the reserved subjects. The provincial council could decide the budget in so far it related to the transferred subjects. Executive machinery dealing with those subjects was placed under the direct control of provincial legislature. However, the provincial legislature and the ministers did not have any control over the reserved subjects, which came under the Governor and his Executive council.[1][2][4][5]

| Council | Term |

|---|---|

| First | 17 December 1920 – 11 September 1923 |

| Second | 26 November 1923 – 7 November 1926 |

| Third | November 1926 - October 1930 |

| Fourth | October 1930 - November 1934 |

| Fifth | November 1934 - January 1937 |

The Council had a total of 127 members in addition to the ex - officio members of the Governor's Executive Council. Out of the 127, 98 were elected from 61 constituencies of the presidency. The constituencies comprised three arbitrary divisions - 1)communal constituencies such as non-Muhammadan urban, non-Muhammadan rural, non-Brahman urban, Mohamaddan urban, Mohamaddan rural, Indian Christian, European and Anglo-Indian 2)special constituencies such as landholders, Universities, planters and trade associations (South India Chamber of Commerce & Nattukottai Nagarathar Association) and 3) territorial constituencies. 28 of the constituencies were reserved for non-Brahmans. 29 members were nominated, out of whom a maximum of 19 would be government officials, 5 would represent the Paraiyar, Pallar, Valluvar, Mala, Madiga, Sakkiliar, Thottiyar, Cheruman and Holeya communities and 1 would represent the "backward tracts". Including the Executive Council members, the total strength of the legislature was 134.[1][2][4][6]

The first election for the Madras Legislative Council, under this Act was held in November 1920. The first sitting of the Council was inaugurated by the Duke of Connaught on 12 January 1921. In total, five such councils were constituted (in 1920, 23, 26, 30 and 34). The term of the councils was three years (except for the fourth council which was extended for a year in expectation of abolition of dyarchy ). While the first, second and fourth Councils were controlled by Justice Party majorities, the third Council was characterised by a fractured verdict and an independent ministry. The fifth council also saw a fractured verdict and a minority Justice government.[2][7]

Provincial autonomy (1937-50)

| Group | Seats |

|---|---|

| General | 35 |

| Mohammadans (Muslims) | 7 |

| Indian Christians | 3 |

| Europeans | 1 |

| Nominated by Governor | 8-10 |

| Total | 54-56 |

The Government of India Act of 1935 abolished dyarchy and ensured provincial autonomy. It created a bicameral legislature in the Madras province. The Legislature consisted of the Governor and two Legislative bodies - a Legislative Assembly and a Legislative Council. The Assembly consisted of 215 members, who were further classified into general members and reserved members representing special communities and interests.[2][9] The Council consisted of a minimum of 54 and a maximum of 56 members. It was a permanent body not subject to dissolution by the Governor and one-third of its members retired every three years. 46 of its members were elected directly by the electorate while the Governor could nominate 8 to 10 members. Similar to the council, the electable members were further classified into general and reserved members. Specific number of seats were reserved (allocated) to various religious and ethnic groups. The Act provided for a limited adult franchise based on property qualifications.[10] Seven million people, roughly 15% of the Madras people holding land or paying urban taxes were qualified to be the electorate.[9] Under this Act, two councils were constituted - the first in 1937 and the second in 1946. Both Councils were controlled by Congress majorities.

In Republic of India (1950-86)

After India became independent in 1947 and the Indian Constitution was adopted in 1950, the Legislative Council continued to be the upper chamber of the legislature of the Madras State - the successor to Madras Presidency. It continued to be called as the "Madras Legislative Council". The Council was a permanent body and was not subject to dissolution. The length of a member's term was six years and one-third of the members retired every two years. The strength of the Council was not less than 40 or more than one-third of the strength of the Assembly. The following table illustrates how the members of Council were selected:

| Proportion | Method of Selection |

|---|---|

| One-sixth (1/6th) | Nominated by the Governor on the advice of the cabinet. They were supposed to have excelled in fields like arts, science, literature, cooperative movement or social service |

| One-third (1/3rd) | Elected by the members of the Legislative Assembly by proportional representation using the Single Transferable Vote System |

| One-third (1/3rd) | Elected by the members of local self governmental bodies like corporations, municipalities and district boards. |

| One-twelfth (1/12th) | Elected by an electorate consisting of electors who have held Graduate degrees for a minimum of three years |

| One-twelfth (1/12th) | Elected by an electorate consisting of teachers of secondary schools, colleges and universities with a minimum experience of three years |

The actual strength of the council varied from time to time. During 1952–53, it had a strength of 72. After the formation of Andhra state on 1 October 1953, its strength came down to 51. In 1956 it decreased to 50 and the next year increased again to 63 - where it remained till the council's abolition. Of those 63, local bodies and the assembly elected 21 each, the teachers and graduates elected 6 each and the remaining 9 were nominated.[11] The Council could not pass legislation on its own - it had to approve or disapprove the laws passed by the Assembly. In case of conflict between the Council and the Assembly, the will of the later would prevail.[12][13] When Madras state was renamed as Tamil Nadu in 1968,[14] the name of the council also changed to "Tamil Nadu Legislative Council".

Abolition

The legislative council was abolished in 1986 by the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) government of M. G. Ramachandran (MGR) . MGR had nominated a Tamil film actress, Vennira Aadai Nirmala (aka A. B. Shanthi) to the Council. Her swearing in ceremony was scheduled for 23 April 1986. Nirmala had earlier declared insolvency and according to Article 102-(1)(c) of the Indian Constitution, an insolvent person can not serve as a member of parliament or state legislature. On 21 April, a lawyer named S. K. Sundaram, filed a public interest writ petition in the Madras High Court challenging Nirmala's nomination to the Council. MGR loaned Nirmala a sum of Rupees 4,65,000 from ADMK's party funds to pay off her creditors,[15][16] so that her insolvency declaration could be annulled. The same day, Nirmala's lawyer Subramaniam Pichai, was able to persuade judge Ramalingam to set aside her insolvency. He used a provision in the Section 31 of The Presidency Towns Insolvency Act of 1909, which allowed a judge to annul an insolvency retrospectively if all debts had been paid in full. This annulment made Nirmala's nomination valid and the writ petition against it was dismissed. However, Nirmala withdrew her nomination to the council. The Governor of Tamil Nadu, Sundar Lal Khurana asked MGR to explain how Nirmala's nomination was proposed without proper vetting. This incident caused an embarrassment to MGR. Then a rumor arose that President of the main opposition party and former Chief minister M Karunanidhi, who was not an MLA at that time, planned to enter the legislative council, and trouble the Chief minister from both Houses in the Legislature, as the Chief Minister was a member of the Lower House. Following such unwanted events and miffed with rumors, MGR decided to abolish the council once for all.[17][18][19][20][21]

On 14 May, a resolution seeking to abolish the council was moved successfully in the legislative assembly. The Tamil Nadu Legislative Council (Abolition) Bill, 1986 was passed by both houses of the Parliament and received the assent of the president on 30 August 1986. The Act came into force on 1 November 1986 and the council was abolished.[2]

Revival attempt

The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) has so far made three unsuccessful attempts to revive the council. Revival of the Legislative Council was one of the promises included in the election manifesto of Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) in the 2006 Assembly elections. The DMK won the 2006 assembly election and M. Karunanidhi became Chief minister. In his inaugural address to the 13th Legislative Assembly delivered on 24 May 2006, Governor Surjit Singh Barnala said steps will be taken to move the necessary constitutional amendments for reviving the council.[17] On 12 April 2010, the Legislative Assembly passed a resolution seeking to revive the Council.[22] The DMK's earlier attempts to revive the council, when it was in power during 1989–91 and 1996-2001 were not successful, as it did not possess both the two-thirds majority in the Legislative Assembly and a friendly union government necessary for it to be done.[23] On both occasions, the ADMK governments that followed the DMK governments passed counter resolutions to rescind them (in October 1991 and July 2001 respectively).[11] The Tamil Nadu Legislative Council Bill, 2010 was approved by the Indian cabinet on 4 May 2010[24] and was passed by both the houses of the Indian Parliament.[25] Constituencies for the new house were identified in September 2010.[26] Work on preparation of electoral rolls for them began in October 2010 and was completed by January 2011.[27] However, in February 2011, the Supreme Court of India stayed the elections to the new council, till the petitions challenging its revival could be heard.[28] In the 2011 Assembly elections, the AIADMK came out with a sweeping majority. The AIADMK government headed by J.Jayalalitha expressed its intention not to revive the council. The government once again passed a counter resolution to withdraw the attempt to revive the council. Ahead of the 2021 Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly election, the BJP has promised revival of the Council in its manifesto.[29]

Location

Fort St. George has historically been the seat of the Government of Tamil Nadu since colonial times. During 1921–37, the Madras Legislative Council met at the council chambers within the fort. Between 14 July 1937 – 21 December 1938, the assembly met at the Senate House of the University of Madras and between 27 January 1938 - 26 October 1939 in the Banqueting Hall (later renamed as Rajaji Hall) in the Government Estate complex at Mount Road. During 1946–52, it moved back to the Fort St. George. In 1952, the strength of the assembly rose to 375, after the constitution of the first legislative assembly, and it was briefly moved into temporary premises at the government estate complex. This move was made in March 1952, as the existing assembly building only had a seating capacity of 260. Then on 3 May 1952, it moved into the newly constructed assembly building in the same complex. The legislature functioned from the new building (later renamed as Kalaivanar Arangam during 1952–56. However, with the reorganisation of states and formation of Andhra, the strength came down to 190 and the legislature moved back to Fort St. George in 1956. From December 1956 till January 2010, the Fort remained the home to the legislature .[30][31][32] In 2004, during the 12th assembly, the ADMK Government under J. Jayalalitha made unsuccessful attempts to shift the assembly (the council had been abolished by then), first to the location of Queen Mary's College and later to the Anna University campus, Guindy. Both attempts were withdrawn after public opposition.[33] During the 13th Assembly, the DMK government led by M. Karunanidhi proposed a new plan to shift the assembly and the government secretariat to the a new building in the Omandurar Government Estate. In 2007, the German architectural firm GMP International won the design competition to design and construct the new assembly complex. Construction began in 2008 and was completed in 2010. The assembly functioned in the new assembly building during March 2010 - May 2011. In May 2011, the Tamil Nadu legislature was moved back to Fort St. George.[33][34][35][36][37]

List of historical locations where the Tamil Nadu Legislative Council has been housed:

| Duration | Location |

|---|---|

| 1921–1937 | Council chambers, Fort St. George |

| 14 July 1937 – 21 December 1938 | Senate House, Madras University Campus, Chepauk |

| 27 January 1938 – 26 October 1939 | Banqueting Hall (Rajaji Hall), Government Estate (Omandurar Estate), Mount Road |

| 24 May 1946 – 27 March 1952 | Council chambers, Fort St. George |

| 3 May 1952 – 27 December 1956 | Kalaivanar Arangam, Government Estate (Omandurar Estate) |

| 29 April 1957 – 30 March 1959 | Assembly Hall, Fort St. George |

| 20–30 April 1959 | Aranmore Palace, Udhagamandalam (Ooty) |

| 31 August 1959 - 1 November 1986 | Assembly Hall, Fort St. George |

Chief Ministers from the Council

During its existence as the upper chamber of Tamil Nadu Legislature, the Council has been used thrice to appoint non-members of the Legislature as Chief Minister. The first time this happened was when P. S. Kumaraswamy Raja was nominated by governor Krishna Kumarsinhji Bhavsinhji to the Council so that Kumaraswamy Raja could become chief minister. In 1952, C. Rajagopalachari (Rajaji) was nominated by Governor Sri Prakasa to the Council so that Rajaji could become chief minister.[38][39] The third time was in 1967 when C. N. Annadurai became the chief minister first and then got himself elected to the Council.[40][41]

Presiding Officers

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

During 1861–1937, the presiding officer of the Madras Legislative Council was known as the "President of the Council". From its establishment in 1861 till dyarchy was introduced in 1921, the Governor of Madras was also the President of the Council. After dyarchy introduced, the first and second council presidents, Perungavalur Rajagopalachari and L. D. Swamikannu Pillai, were appointed by the Governor himself. The presidents who came after them were chosen by the Council itself. During 1937–86, the presiding officer was called as the "Chairman of the Council".[42] The following table lists the presiding officers of the Council.[7][43][44][45]

| Chairman of Tamil Nadu Legislative Council | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Status | Abolished |

| Appointer | Governor of Tamil Nadu |

| Term length | Six years |

| Inaugural holder | William Denison |

| Formation | 18 February 1861 |

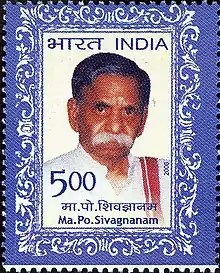

| Final holder | M. P. Sivagnanam |

| Abolished | 1 November 1986 |

| Website | www.tn.gov.in |

| # | Name | Took office | Left office | Political party |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governors of Madras (1861–1920) | ||||

| 1 | William Thomas Denison | 18 February 1861 | 26 November 1863 | |

| 2 | Edward Maltby (acting) | 26 November 1863 | 18 January 1864 | |

| 3 | William Thomas Denison | 18 January 1864 | 27 March 1866 | |

| 4 | Lord Napier | 27 March 1866 | 19 February 1872 | |

| 5 | Alexander John Arbuthnot (acting) | 19 February 1872 | 15 May 1872 | |

| 6 | Lord Hobart | 15 May 1872 | 29 April 1875 | |

| 7 | William Rose Robinson (acting) | 29 April 1875 | 23 November 1875 | |

| 8 | Duke of Buckingham and Chandos | 23 November 1875 | 20 December 1880 | |

| 9 | William Huddleston (acting) | 24 May 1881 | 5 November 1881 | |

| 10 | Mountstuart Elphinstone Grant Duff | 5 November 1881 | 8 December 1886 | |

| 11 | Robert Bourke, Baron Connemara | 8 December 1886 | 1 December 1890 | |

| 12 | John Henry Garstin | 1 December 1890 | 23 January 1891 | |

| 13 | Bentley Lawley, Baron Wenlock | 23 January 1891 | 18 March 1896 | |

| 14 | Arthur Elibank Havelock | 18 March 1896 | 28 December 1900 | |

| 15 | Arthur Oliver Villiers-Russell, Baron Ampthill | 28 December 1900 | 30 April 1904 | |

| 16 | James Thompson (acting) | 30 April 1904 | 13 December 1904 | |

| 17 | Arthur Oliver Villiers-Russell, Baron Ampthill | 13 December 1904 | 15 February 1906 | |

| 18 | Gabriel Stoles (acting) | 15 February 1906 | 28 March 1906 | |

| 19 | Arthur Lawley, Baron Wenlock | 28 March 1906 | 3 November 1911 | |

| 20 | Thomas David Gibson-Carmichael, Baron Carmichael | 3 November 1911 | 30 March 1912 | |

| 21 | Sir Murray Hammick (acting) | 30 March 1912 | 30 October 1912 | |

| 22 | John Sinclair, Baron Pentland | 30 October 1912 | 29 March 1919 | |

| 23 | Sir Alexander Gordon Cardew | 29 March 1919 | 10 April 1919 | |

| 24 | George Freeman Freeman-Thomas, Baron Willingdon | 10 April 1919 | 12 April 1924 | |

| During dyarchy (1920–1937) | ||||

| 1 | Sir P. Rajagopalachari | 1920 | 1923 | Non-Partisan |

| 2 | L. D. Swamikannu Pillai | 1923 | September 1925 | Justice Party |

| 3 | M. Ratnaswami | September 1925 | 1926 | |

| 4 | C. V. S. Narasimha Raju | 1926 | 1930 | Swaraj Party |

| 5 | B. Ramachandra Reddi | 1930 | 1937 | Justice Party |

| During Provincial Autonomy (1937–1946) | ||||

| 1 | U. Rama Rao | 1937 | 1945 | Indian National Congress |

| In Republic of India (1950–1986) | ||||

| 1 | R. B. Ramakrishna Raju | 1946 | 1952 | Indian National Congress |

| 2 | P. V. Cherian | 1952 | 20 April 1964 | Indian National Congress |

| 3 | M. A. Manickavelu Naicker | 1964 | 1970 | Indian National Congress |

| 4 | C. P. Chitrarasu | 1970 | 1976 | Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam |

| 5 | M. P. Sivagnanam | 1976 | 1986 | Tamil Arasu Kazhagam |

See also

References

- S. Krishnaswamy (1989). The role of Madras Legislature in the freedom struggle, 1861-1947. People's Pub. House (New Delhi). pp. 5–70, 72–83.

- "The State Legislature - Origin and Evolution". Tamil Nadu Government. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- K. C. Markandan (1964). Madras Legislative Council; Its constitution and working between 1861 and 1909. S. Chand & CO. p. 76.

- "Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly". Government of India. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- Rajaraman, P. (1988). The Justice Party: a historical perspective, 1916-37. Poompozhil Publishers. p. 206.

- Mithra, H.N. (2009). The Govt of India ACT 1919 Rules Thereunder and Govt Reports 1920. BiblioBazaar. pp. 186–199. ISBN 978-1-113-74177-6.

- Rajaraman, P. (1988). The Justice Party: a historical perspective, 1916-37. Poompozhil Publishers. pp. 212–220.

- "Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly". Indian Government. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- Christopher Baker (1976), "The Congress at the 1937 Elections in Madras", Modern Asian Studies, 10 (4): 557–589, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00014967, JSTOR 311763, S2CID 144054002

- Low, David Anthony (1993). Eclipse of empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-521-45754-5.

- Ramakrishnan, T (8 April 2010). "Legislative Council had chequered history". The Hindu. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- Darpan, Pratiyogita (2008), "Public Administration Special", Pratiyogita Darpan, 2 (22): 60

- Sharma, B. K. (2007). Introduction to the Constitution of India. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. pp. 207–218. ISBN 978-81-203-3246-1.

- "C. N. Annadurai: a timeline". The Hindu. The Hindu Group. 15 September 2009.

- "Rs. 4.5 lakh-fine slapped on 'Vennira Aadai' Nirmala". The Hindu. The Hindu Group. 14 June 2002. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Court imposes Rs. 4.65-lakh fine on Vennira Adai Nirmala". The Hindu. The Hindu Group. 6 June 2007. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- "TN to get back Upper House". Rediff.com. 24 May 2006. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- indiaabroad (4 March 2009). "Jayaprada's status as MP in jeopardy". Yahoo!. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- Randor Guy (17 March 2009). "Crime Writer's Casebook-ANJALI DEVI CASE-2". Galatta. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- Randor Guy (26 March 2009). "Crime writer's casebook- Vennira Aadai Nirmala Case-2". Galatta. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- India Today, Vol 11 (1986). Council Caper. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Assembly votes for Legislative Council". The Hindu. 12 April 2010. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- Arun Ram (26 May 2006). "Tamil Nadu to have Upper House". Daily News and Analysis. Diligent Media Corporation. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- "Cabinet clears State Legislative Council proposal". The Hindu. 4 May 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- "Parliament nod for Council Bill". The Hindu. 6 May 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- Delimitation of Council Constituencies (Tamil Nadu), Order 2010 Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Announcement on electoral roll revision". The Hindu. 24 October 2010. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- "SC stays TN council elections". The Times of India. 22 February 2011. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- https://www.bjp.org/u2/Tamil_Nadu_2021_Assembly_Election_BJP-Vision_Document_English.pdf

- Karthikeyan, Ajitha (22 July 2008). "TN govt's new office complex faces flak". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- S. Muthiah (28 July 2008). "From Assembly to theatre". The Hindu.

- "A Review of the Madras Legislative Assembly (1952-1957) : Section I, Chapter 2" (PDF). Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- S, Murari (15 January 2010). "Tamil Nadu Assembly bids goodbye to Fort St George, to move into new complex". Asian Tribune. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- Ramakrishnan, T (11 March 2010). "State-of-the-art Secretariat draws on Tamil Nadu's democratic traditions". The Hindu. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Ramakrishnan, T. (19 April 2008). "New Assembly complex to have high-rise building". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- Ramakrishnan, T (13 March 2010). "Another milestone in Tamil Nadu's legislative history". The Hindu. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Ramakrishnan, T (24 May 2011). "After 16 months, Assembly back at Fort St. George". The Hindu. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- C. V. Gopalakrishnan (31 May 2001). "Of Governors and Chief Ministers". The Hindu. The Hindu Group. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - T. V. R. Shenoy (22 August 2001). "From Rajaji to Jayalalithaa". Rediff.

- Pushpa Iyengar, Sugata Srinivasaraju, "Where The Family Heirs Loom", Outlook India, retrieved 16 November 2009

- Gopal K. Bharghava, Shankarlal C. Bhatt (2005). Land and people of Indian states and union territories. 25. Tamil Nadu. Delhi: Kalpaz Publications. p. 525. ISBN 81-7835-356-3.

- Johari, J. C (2007). THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA A Politico-Legal Study. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 226. ISBN 978-81-207-2654-3.

- "Legislative Council to be revived: Karunanidhi". The Hindu. 7 April 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- Naidu, R. Janardhanam; K. Ramalingam; V. Subbiah (1974). Bharani's Madras handbook.

- "List of Governors of Madras, Provinces of British India". Worldstatesman. Retrieved 5 May 2010.